- Image via Wikipedia

A long time ago, in a publishing universe far, far away, publishers had it good. They controlled content, distribution, and manufacturing. They became experts at using the postal system, and charged for it. They became experts at making beautiful vessels for content, and charged for them. And whether the content they sent was ephemeral (news) or enduring (books), they charged for it. Everything they did cost money, and because they owned the addressable audience by virtue of controlling distribution, they could charge for that, as well — and advertisers paid.

But during the initial days of online fever, publishers became convinced to two fallacies — distribution would be free, so it wasn’t going to be a major commercial factor; and the containers for content wouldn’t matter since they’d just be network terminals and devices.

These notions were summed up in the meme of the time, “Content is king.”

Hindsight shows how wrong that was.

The digital revolution wrested two major aspects of publishing from publishers — distribution and manufacturing (and, increasingly, the attention of the audience). Publishers still mail stuff and print stuff, but print’s not nearly as sexy as it used to be and the mail’s slow and inefficient. It’s like a slow-motion liquidation sale, watching these two former advantages deplete themselves of value.

Losing 2/3 of their advantages has led to some predictable shifts in profitability for publishers — namely, far less of it. There’s just less to mark up.

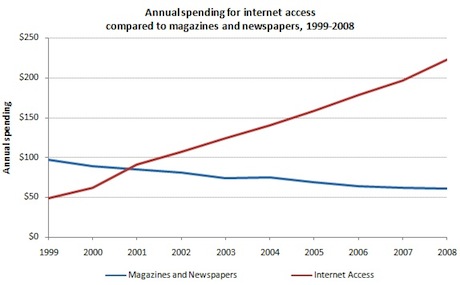

But it’s another story entirely for the new distributors and device manufacturers, because people are more than willing to pay for digital distribution and sexy content vessels — fast connections, portable connectivity, and cool toys. A recent article in the New York Times shows how quickly costs for information have skyrocketed, mostly because people are paying for broadband and devices:

It used to be that a basic $25-a-month phone bill was your main telecommunications expense. But by 2004, the average American spent $770.95 annually on services like cable television, Internet connectivity and video games, according to data from the Census Bureau. By 2008, that number rose to $903, outstripping inflation. By the end of this year, it is expected to have grown to $997.07. Add another $1,000 or more for cellphone service and the average family is spending as much on entertainment over devices as they are on dining out or buying gasoline.

Even radio — a “free” medium — cost the average American $12.25 this year, up from $1.19 in 2004.

Nicholas Carr picked up the article and extended his “Information wants to be free my ass” post, offering the following chart of just Internet access fees to show how much all this free information is costing. Remember, we used to charge for distribution — boy, what a bargain print distribution prices seem now!

If he who pays the piper calls the tune, and content providers are essentially the pipers now, it looks like the distributors and manufacturers of the Digital Age will be calling the tune.

Where does this leave publishers? It’s clear to me — they have to recognize that all they’re left with is their content, and they should charge for it. The piper can still make a good living. Arguments about how that pricing should be determined will run rampant, but there is no right or wrong answer here. There’s no price point we can know a priori. Price will continue to be what the market will bear.

Based on the price elasticity the device and distribution market has been able to carve out by embracing digital strategies, the future for content providers may be bright, as well — if we play our tunes well, using modern instruments.

And that posture differs greatly from the arrogance of a king.

Discussion

15 Thoughts on "Distribution Doesn’t Matter? Content Vessels Are Irrelevant? Device Makers and Broadband Providers Are Laughing All the Way to the Bank"

Kent,

Doesn’t that graph suggest a way for this to work. The folks getting in all the money need to start paying for the content they are serving over their wires/networks and airwaves.

ISPS need to start paying content creators for their content. That may not save publishers as they are currently built but it might well save professional writing, authorship and journalism!

It’s amazed me that this has been ignored for so long.

Eoin

I agree. The piper (the content provider in that old saw) needs to know how rich the payers are, and start demanding more. I’m amazed, as well. Society publishers in particular I think are shy about pricing to market, and the separation at many purchasers (institutions in particular) between IT and library purchasers contributes, too. For instance, if the library knew how much the institution were paying for its T3 and network services, a content bundle might look like a bargain in comparison.

Sounds to me like the broadband market in the US is a monopoly. Prices in the UK are much less: £25 per month tops for an all you can eat type broadband package. You’ll probably get some kind of landline thrown in with that.

Over here at least, the ISPs went for perceived data speed instead of pricing for amount of data. This was/is a mistake. Pricing for consumption at the point of use is the way to regulate demand – that way the ISPs would have the money to invest in the infrastructure to support the P2P traffic, because those P2P folks would be paying for all their downloads. This would also act as a brake to piracy, which (at least in the UK) the current model does not. They just download after midnight.

As scholarly publishers we’ve GOT to be supporters of net neutrality surely?!

It seems to me that the internet has made the market for information absolutely brutally efficient. The tendencies of large numbers of content providers to create content simply by sticking a byline on a PR release has been ruthlessly exposed (sorry, nobody should pay for that rubbish).

I think content distributors should recognise that in a digital world the relative value of their content will be unique to each consumer of that content. This would appear to be what the NY Times are seriously trying to do, and the fact that many folks have ripped into them for taking their time, shows the lack of understanding about what they are working on. It’s not like the web doesn’t give us back exactly the information we need to do this. I’ll grant you that it is a distinctly non-trivial problem to solve, but it is solvable. There’s papers on the subject out there.

The Murdoch approach to charging is flawed because it’s predicated on the belief that “Of course our content is valuable, look at the shiny offices we inhabit” rather than actually working out what bits of the content have value and to whom.

It’s my understanding that the Huffington Post has an algorithm that looks at the analytics of articles within the site, and moves them to better (or worse) positions in response to the traffic flow dynamics. That’s smart thinking. It’s web thinking. It’s thinking that recognises the myriad things that affect the perceived value of a piece of content. It’s Digital thinking.

It’s time to spend some money understanding the numbers that underpin the consumption of our content, the ebbs and flows of traffic. For the visitors we all receive are telling us useful things about the value of our content. That’s going to lead to meaningful insight on how to price our stuff properly. The smart players out there are doing exactly that.

Distribution? Manufacturing? Publishers should be in the business of content. The challenge in today’s environment is how to move forward when your enterprise has a fundamental lack of understanding of what its core competency is.

I think it’s an illusion to think that publishers have been in the business of content alone. They’ve been in the business of selling manufactured print items, and did this most effectively when they also controlled the distribution channels (either through postal distribution or consignment distribution for books). They could also commercialize the audience when they controlled postal distribution because they owned the list of the audience, so advertisers had to go through them. Look at how many people at a typical publisher dealt with distribution and manufacturing in the 1990s. I’ll bet in most places it was more than dealt with editorial.

If distribution and manufacturing weren’t important, then publishers could have thrived just telling stories around a campfire.

Given that so many of these things (printing, warehousing, fulfillment, internet platforms) are outsourced these days, are they still really within the core competency for most publishers?

No one said that manufacturing and distribution are not important, just that they are fundamentally different businesses. Publishers who operated under the illusion (and, as you point out, invested accordingly) that they were in the business of printing words on a page and putting a book in a box are struggling now to define their value … because they never really understood it to begin with.

Thanks for the post and the data Kent – what we have seen is not a reduction in consumer money spent on content, but an increase and a shift away from content producers. I believe that you are right to argue that the industry isn’t looking at this bigger picture, and positioning itself better among the distributors and platform providers, as well as positioning content products better along supply channels to increase their value.

One of the problems for many content producers is not avenues to customer, channel proliferation has been rampant in recent years, it’s their ability to work each channel and price effectively. In the nineties we saw a trend where software companies and content companies got closer. Nowadays publishers need to work more effectively with new distribution partners, working on better revenue models and cost and profit sharing.

By the way, I might agree with you about manufacturing in the past, but publishers were never really very good at that when doing it themselves. Many got burned and innovation and investment were not best delivered by a publisher-manufacturer! The supply that matters is the author / writer, whereas the distribution of products matters as much now as it ever did.

Thanks, Stephen. I agree with your take, but will expand on the final point. Whether publishers were “really very good” at manufacturing in the past isn’t the issue — it’s whether they could move their price point up based on the perception (and reality) of an expensive finished good being delivered.

Two quick points…

First, Carr’s data is problematic as “Internet” really represents many things, including the specific purchase of cable content. People access considerably more content today then in the past, which is not represented.

Second, we are moving from a position of relative content scarcity to widely offered at many places. The new distribution channels have changed the game. News is clearly the hardest hit by this problem. Unfortunately for newspapers, they chose to run more news feeds, devaluing their own product. Why buy the local paper if they are 90% fed by feeds? They should have focused on unique news–local news.

Yes, we’re not in the age of information scarcity, as you note. But I’ll bet that per dollar spent, we’re leaving more information outlets idle than we used to. That is, we’re paying for excess capacity of information in a general manner (too many devices) and per-device (600 channels, but 60% of our viewing is limited to Comedy Central, NESN, and NECN here in Boston, for a 0.5% utilization rate). But we don’t have metered billing. The providers are bundling it all up for cross-subsidization, just like print publishers do with magazines and newspapers (or Elsevier does with the Big Deal). So, I don’t know if people access multiple times more content than in the past or just a little bit more content than in the past, but they certainly pay to have it available in more places and through more systems — which is why the device makers and distributors are getting so rich.

News’ problem is that the content is disposable commodity content, and it’s easily improved upon through a blog comment that gives it context or a news broadcast. I always love it when the TV morning news shows read the papers to us. I always wonder who’s making more money from those news items — the TV news show or the newspaper.

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=c6a7224f-0622-4903-8461-e5094e0d237e)