Delmore Schwartz famously said that even paranoids have enemies. This is worth remembering as we look at the collection of kooks, loonies, ne’er-do-wells, cynics, and hucksters who have taken up the cause of disruptive technology. Recently Jill Lepore wrote a provocative piece in The New Yorker, which was heartily endorsed in the Scholarly Kitchen, in which she took this army of misfits and anarchists to task. Actually, I think she could have gone further. Many of the agents of disruption are reckless and irresponsible, trading on fear as they gleefully propose to tear down just about every institution. Still and all, Lepore got it wrong in attacking the lion of disruptive technology, Clayton Christensen. Christensen does have enemies, and they are following him—and all of us, Lepore included.

The uproar from Lepore’s article means that it is being read by far more than the narrow sliver of the cultural elite that regularly reads The New Yorker. Among Lepore’s stalkers thus are the investors who have made hundreds of millions betting on Christensen’s thesis, sums large enough to require a bit of persuasion to get anyone to seek another rabbi. (Matthew Arnold: Jacobinism loves a rabbi.) Who is this Lepore person they ask, as they (disruptively) Google her. So she teaches at Harvard. Well, that’s neither here nor there. Heck, even Zuck went to Harvard, though he had the good sense to leave. But is she perhaps on the board of any companies? That would be an interesting sign: an organization that can accommodate this rejection of Christensen may invite challengers. Lepore’s article, in other words, is an inverse business opportunity.

Other business types may choose to use Lepore’s piece as a heuristic tool. Since management teams routinely conceal information from their Boards (true in the for-profit and not-for-profit worlds alike), asking the management what they think of Lepore’s article is a way of gauging whether the company is up for the task of competing in a relentless and heartless marketplace, which is the only kind there is. So you like the Lepore piece. Have you considered looking for another job?

Lepore’s piece would be easier to dismiss if it were not so well written–this is The New Yorker, after all. Here is my favorite passage:

There wasn’t much to do. Mainly, we sat at our desks and wrote wishy-washy poems on keyboards manufactured by Digital Equipment Corporation, left one another sly messages on pink While You Were Out sticky notes, swapped paperback novels—Kurt Vonnegut, Margaret Atwood, Gabriel García Márquez, that kind of thing—and, during lunch hour, had assignations in empty, unlocked offices.

I laughed out loud when I read that. But afterward I began to ponder if Lepore had properly cited that disruptive technology of disruptive technologies, the Pill, which made casual and amusing assignations in empty offices common. It’s a funny thing about disruptive technology: we like it when we wield the sword, but curse it when the sword threatens our own heads. (Ned Stark: This sword is made of Valyrian steel.)

I came to admire Christensen because he helped to explain a puzzling business situation for me. In 1999 I was running an Internet software company called Tribal Voice. We had been approached by AT&T about a deal, which soon escalated into high-level discussions about an acquisition. Ultimately AT&T declined to buy the company (which is why I continue to work for a living), but during the negotiations I traveled to the AT&T headquarters in Basking Ridge, NJ a number of times and got to know many of their people fairly well.

I was profoundly impressed by AT&T and its people. They were smart, worked long days, listened hard, and studied things carefully. These were the kind of people who did their homework. I was shown a library of “briefing books” they had prepared on companies of interest to them. I had never seen the like before, despite having spent some time in large media corporations. How could this company, with its global reach, its best-in-class network, a balance sheet richer than Croesus, and it people, its very, very talented group of people, do anything but grow and expand, continuing to dominate the world of telecommunications as it had for a century?

Back home in Silicon Valley, though, it was a different story. “You had a meeting at AT&T?” someone said to me. “Those idiots.” Already the word was out that AT&T did not “get” the Internet. They had, after all, famously turned it down when the U.S. government proposed that AT&T take it over. (Can you imagine that? Can you imagine what it would mean to own the Internet?) AT&T was big and bureaucratic and their people stupid, stupid, stupid. One of my Board members assured me that if I were able to close the deal, his venture capital firm would do everything possible to make sure that I would not have to go to work there for a period of time. It was a retelling of David and Goliath, and all bets were on the unwashed tribe of Davids in Santa Clara and San Jose. No network operations center, no briefing books, not even a necktie.

AT&T ultimately stumbled and was itself sold to one of its former subsidiaries, which took the AT&T name. The new firm is in fact a leader in providing Internet access (poor service notwithstanding), which is a cruel irony. It was a couple years before I could explain this to myself, however. That was when I stumbled on Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma.

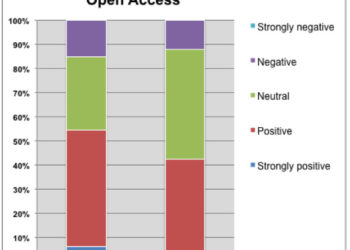

The Innovator’s Dilemma helps to explain why some of the best and well-managed companies, with resources that should make the competition tremble, somehow or other lag upstarts in coming up with innovations. We see this very clearly in the world of scholarly communications, where the Gold OA model was developed first not by Elsevier or Springer but by BMC, and where community sharing networks had their beginning at Mendeley. Established companies come up with backward-looking “new” ideas like the Article of the Future and then have to go out and acquire the likes of Mendeley to bring real innovation in house. Go ahead and argue about what is and is not an innovation and when an innovation is disruptive. Meanwhile, if you have a truly new idea, don’t you think you would be better off doing it outside the confines of a big company? When it comes to innovation, people tend to vote with their feet.

Established companies know who their customers are, and that is their undoing. They do the homework. They aim to please those customers and come up with feature after feature that meets the needs of those customers. In the world of journals publishing this has taken the form of endless requirements to service the largest sales channel, academic libraries. So now we have such frills as endless metrics, COUNTER compliance, rules for transitioning journals from one publisher to another, etc., etc. Some readers will leap up and say those things are absolutely necessary, and for some markets, they are. Meanwhile, barebones services are cropping up everywhere including most dramatically at PLOS ONE. The key to PLOS ONE is not new features but defeaturing, a stripped-down form of peer review which is trumpeted as the new lemonade. The Gold OA business has developed an entirely new class of customer, authors. No wonder that Elsevier, Springer et al., did not come up with this first: they were focused on libraries.

The question that Christensen answered for me was that AT&T could be smart but still get it wrong. It doesn’t matter how hard you work if you are looking at the wrong thing. You can do all the homework and master the recommended reading, but the important thing is not to know everything but to know the one thing that will make a difference. How to know that one thing remains a mystery, but at least Christensen tells us where to look: fewer features, a lower cost structure, a new class of customer. People who complain that PLOS ONE does not use traditional peer review entirely miss the point.

Lepore, of course, was trained to do the homework and criticizes Christensen when he doesn’t hand it in himself. But chastizing Christensen for the lunacy of his followers is simply wrong. It’s comparable to blaming Nietzsche for Hitler or the Beatles for the music (?) of Metallica.

The New Yorker and the class of public intellectuals like Lepore may or not be disrupted themselves, but what makes them vulnerable is their dismissal of the possibility. You can’t wait for the evidence that the person who is holding a gun to your head is going to fire it. You have to act now, even if that means relaxing some of the standards and procedures that have come to define the institutions in which you have risen. We don’t know if MOOCs will nibble at the authority and hegemony of Harvard, but we know that the people behind them will try. Don’t turn around but someone is following you. I said don’t turn around.

Discussion

12 Thoughts on "Doing and Undoing the Homework"

Another great essay, Joe. Christensen’s insights are important, but not a complete unifying theory of innovation or change. Lepore takes down some of the wilder assumptions about it and most importantly the cultural fatalism that has become associated with “disruption” (as opposed to “progress” or “improvement” or “advances”).

The organizational psychology portions of Christensen’s works are perhaps the most important — the management trap you describe with AT&T and associated “group think” behaviors, for instance, as well as the apathy that can emerge in large, successful companies.

To me, the main lesson is that we can’t stop thinking or competing — with our businesses or within the world of ideas. Take some lessons from Christensen, Godin, Shirky, Peters, Kotter, and others, and keep moving forward. And to plant an appropriate earworm, “Don’t Look Back” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3VPLOVJ0u94&feature=kp).

What sticks in my mind here is the problem of the confounding variables. This whole area of study seems to be replete with confounding variables.

We can clearly sense something happening in the world of business development, but perhaps the underlying cause for disruption is actually ridiculously cheap labour in China. If those chips weren’t so damn cheap, then none of this stuff would be happening – no kindle, no iphone mass distribution. No legion of servers in data centres around the world – without cheap labour there is no commodity computing power.

There are deep issues here around the creation and protection of IP – Apple “we’ll steal from anyone” but they also sue don’t they.

When Clayton says disruption can take decades, to me he undermines the very thing he is advocating. That isn’t disruption. There’s a better word for it – evolution. Sometimes evolution runs fast when environments stress the inhabitants, and sometimes it runs slower when things are more stable http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punctuated_equilibrium

Joe great insight. However, it seems to me that companies rich in cash often tend to wait for success before jumping into new innovation with a purchase. Witness Springer’s purchase of BioMedCentral. Of interest will be PLos One. If their submission rate continues a downward spiral will they be on the block? Are they on the block now?

Note that PLOS is a non-profit. There is much less incentive to be “on the block” as nobody can directly benefit from its liquidation. They would just become a foundation, disbursing the retained earnings from an annuity account or some such.

Christensen’s idea of disruption, by his own admission, is struggling to deal with unresolved issues. It is, at this moment a descriptive idea. Theories need predictive power and disruption still is struggling with this with some semi-predictive possibilities still not yet validated sufficiently to raise it to a “theory” in the scientific sense. Lepore’s article focuses on what she has identified as faulty applications, most of those attributable to Christensen.

When we look at innovation we focus on the successes. As with the past in making movies, we don’t look at all the footage on the cutting room floor. Lepore did look at some of these, perhaps in an unbalanced manner. But as pointed out here, there are plenty who have raised the disruption flag, and, often, inappropriately. Sometimes it takes a well crafted piece to rise above the noise of the crowd. Publicly, Christensen seems more disappointed by Lepore’s piece then concerned that it may have “knocked him out of the box”

In the world of business, there are a plethora of management “theories” that have passed across our desk, that now are sitting in rows in discount book shelves. Corporations have paid dearly for the latest consultants to come and spread the “word” only to jump on the next big idea.

As for all those briefing books in large corporation, sometimes Khaneman’s System 1, intuition makes sense. But then there are large companies, as Lepore points out, that have embraced the new successfully, also. Think of 3M and Post its among others. Think Wal Mart that turns the environmental onslaught into a profit center through innovative packaging and energy efficient building design; think Dayton-Hudson that saw the handwriting on the wall and created Target to the benefit of its founders.

As for all those “investors” who made millions on disruption, one must realize that investors as in venture capital are high risk players. Think Soros, Buffet and others who bet against the bank literally and metaphorically. It would be interesting to unpack who these parties are and their track record, including those playing in the dot com bubble or the ’08 melt down based on paper leveraged on thin air. That’s what keeps the betting parlors open in Nevada and the UK. There is no disruptive innovation here to blame those who took down Wall Street. And, in fact, while their problems may have cost a few substantially, many are back while the individual on the street is still suffering the consequences.

The regulated industries represent a more complex situation as the recent supreme court ruling on Aereo and broadcast industries shows and as we have seen in all areas from power generation, water utilities, taxis, and telecommunications, all far from “free market” and what one might want to suggest exposed to the opportunities of possible “disruption

Mapping scientific methods such as creating “theories” does not map cleanly into the social arena. There is no Captain Picard to issue a directive, “Make it so..”

Similar to Moore’s Law which is not a law – just an observation that happens to have remained consistent over a long period of time, leading to ‘crisis as chip boffins struggle to meet ‘demands’ of Moore’s Law’ and other such nonsense.

To your point on the markets, that’s exactly what I was trying to put across in my piece on the Lepore article. Namely that some people get lucky and beat the market (or in some cases get so lucky that they become the market (Buffet)) but over time everything regresses to the mean. You cannot beat the average performance over time, other than by being lucky.

Here’s my main question: have any of us landed Joe for a book deal?