As some regular readers of the Scholarly Kitchen are aware, Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) has been working with users, publishers, and technology providers over the last few years to increase efficiencies in mining content from subscribed, unsubscribed, and open access journals. This work has led to many conversations about everything from licensing norms to XML normalization, and has also led to meetings with government officials trying to sort out what this all means. As in the old joke about Americans and Brits being separated by a common language, we discovered that common definitions are as lacking in such discussions as they are lacking in scientific literature. Accordingly, we approached our friends at the Scholarly Kitchen for permission to disseminate a first attempt at a short primer for publishers.

What is Text Mining?

Text mining is the data analysis of natural language works, using text as a form of data. It is often joined with data mining, the analysis of data works and databases, and is referred to as “text and data mining” or, simply, “TDM.” In this context, text is one form of “unstructured data.”

TDM is different from search. TDM involves using complex software to read and digest digital information far more quickly than a human being can, breaking it down into raw data and text, analyzing it and coming up with new connections. For example, such a connection may be an unexpected pattern in protein interactions that eventually leads to the development of a new drug, or maybe a subtle shift in weather patterns that predicts a downturn in the price of wheat. In many cases, the knowledge to be extracted from the text is spread across a number of sources.

What is the size of the market for text mining?

In 2014, the market for text mining was estimated to exceed $2 billion, with an estimated compound annual growth rate of greater than 25%. This includes both “tools” and “fuels,” as defined below.

Why do people text mine?

Academic researchers use text mining to further research goals in sciences, economics, humanities, linguistics and other fields.

Business people use text mining for various purposes:

- to manage a brand, product, or reputation

- to manage customer experience

- to perform research

- to carry out competitive intelligence

- to search for information, access information, or answer questions

How is the market organized?

To simplify, we recommend using the “tools and fuels” analogy. Some companies, such as Linguamatics, Elsevier, IBM/Watson, SAS, and many smaller startups, provide software tools which enable the mining of text. Businesses and academics also use many homegrown tools. Other companies, such as Twitter, newspapers, and journal publishers, provide content to be mined, essentially the “fuel” for the tools. When discussing text mining, one must keep in mind the distinction.

What are the most popular types of fuel?

According to one study, the top ten categories of text for mining are:

- blogs (long form and micro)

- news articles

- comments on blogs and articles

- customer and market surveys

- online forums

- Facebook postings

- scientific or technical literature

- online reviews

- e-mail and correspondence

- contact-center notes or transcripts

How do users currently mine journal content?

Journal content is mined through JSTOR (social sciences), repositories, A & I services, and direct deals with publishers. Publishers have also been collaborating on pan-industry solutions through CCC, Publishers Licensing Society, and CrossRef. Additionally, many open access publishers make XML feeds readily available from their websites.

What will make it easier for researchers to mine?

- The ability to download full-text XML content obtained directly from multiple publishers from one location;

- The ability to mine across subscribed, unsubscribed and open access content from multiple publishers;

- A common set of terms and conditions for the use of content across multiple publishers; and

- Download results sets into their preferred text mining tools.

What laws govern text mining?

While the exact details vary with the technologies used, TDM may interact with copyright in various ways, including:

- Accessing text (right to make public, control distribution)

- Downloading text (copy)

- Reformatting text (copy, translate)

- Storing text (copy)

- Output including text (copy, derivatives)

The ways in which copyright and exceptions to copyright apply to TDM vary by jurisdiction. In addition to copyright, other areas of laws that may govern text mining include privacy, trade secrets, and contract. Again, the applicability of these areas of law will vary by jurisdiction.

References:

Grimes, Seth, Text Analytics 2014: User Perspectives on Solutions and Providers, http://altaplana.com/TextAnalytics2014.pdf

Gadkari, Pia, How does Twitter make money?, http://www.bbc.com/news/business-24397472

Kaufman, Roy, How Traders Are Using Text and Data Mining to Beat the Market, http://www.thestreet.com/story/13044694/1/how-traders-are-using-text-and-data-mining-to-beat-the-market.html

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Guest Post: CCC’s Roy Kaufman–A Text Mining Primer for Journal Publishers"

Fascinating, Roy. How much of the $2 billion is for fuels? Any idea what fraction of that is going to scholarly publishers?

Roy, Thanks for creating this. It is a good complement to all the very detailed and specific material out there. Thanks for this structure!

I’d add a “who” to your list, and perhaps a “when”:

The “who”:

– there are people who are creating services for others, and those services rely on text mining (Google is an example, in a sense).

– then there are the users of those services

and in another dimension:

– there are organizations that text mine (e.g., pharma companies who want copies of articles for local and private storage, startups who want text from publishers to build their businesses), and

– there are individuals who do this (e.g., researchers who study text mining)

The latter dimension can be important for licensing, I think, since some licenses allow personal use vs. corporate use.

The “when” is just my phrase for getting at what phase we are in now with the TDM capability. At least in my experience right now these are early days where the people who are asking for text or for TDM are often looking for “trial sets” so they can test and tune their algorithms. They often ask for one-time copies of information, rather than needing ongoing flows of information set up.

It would be interesting to know if others are seeing more advanced/production cases now emerging.

Thanks again.

Text and data mining is certainly an upcoming trend the scientific community should look out for (http://www.stm-assoc.org/2015_02_20_STM_Report_2015.pdf). But as mentioned in the post “The ability to mine across subscribed, unsubscribed and open access content from multiple publishers” is central to TDM. So there is need for more clarity in licensing when it comes to cross-publisher TDM.

Roy:

Congrats on a succinct analysis. I agree, the lack of consistent and accepted vocabulary (and or commonly recognized methodologies) make TDM a hoary subject for publishers and licensees to navigate.

From the publisher perspective, I see 3 core problems:

* THE ACCESS LAYER: Most of our content distribution systems were designed from the ground up to protect publisher IP and the integrity of the scientific record that represents. We don’t have an automated way to either pass large scale content/data requests, nor do we have systems designed to support robust TDM natively.

* The LICENSE LAYER: Because TDM is such a generically broad term, its difficult to define permitted uses, data ranges and outcomes that makes a license an enforceable document without a lot of mutual discovery between licensee and publisher. This is a far more complex solution to arbitrate than a standard library access contract.

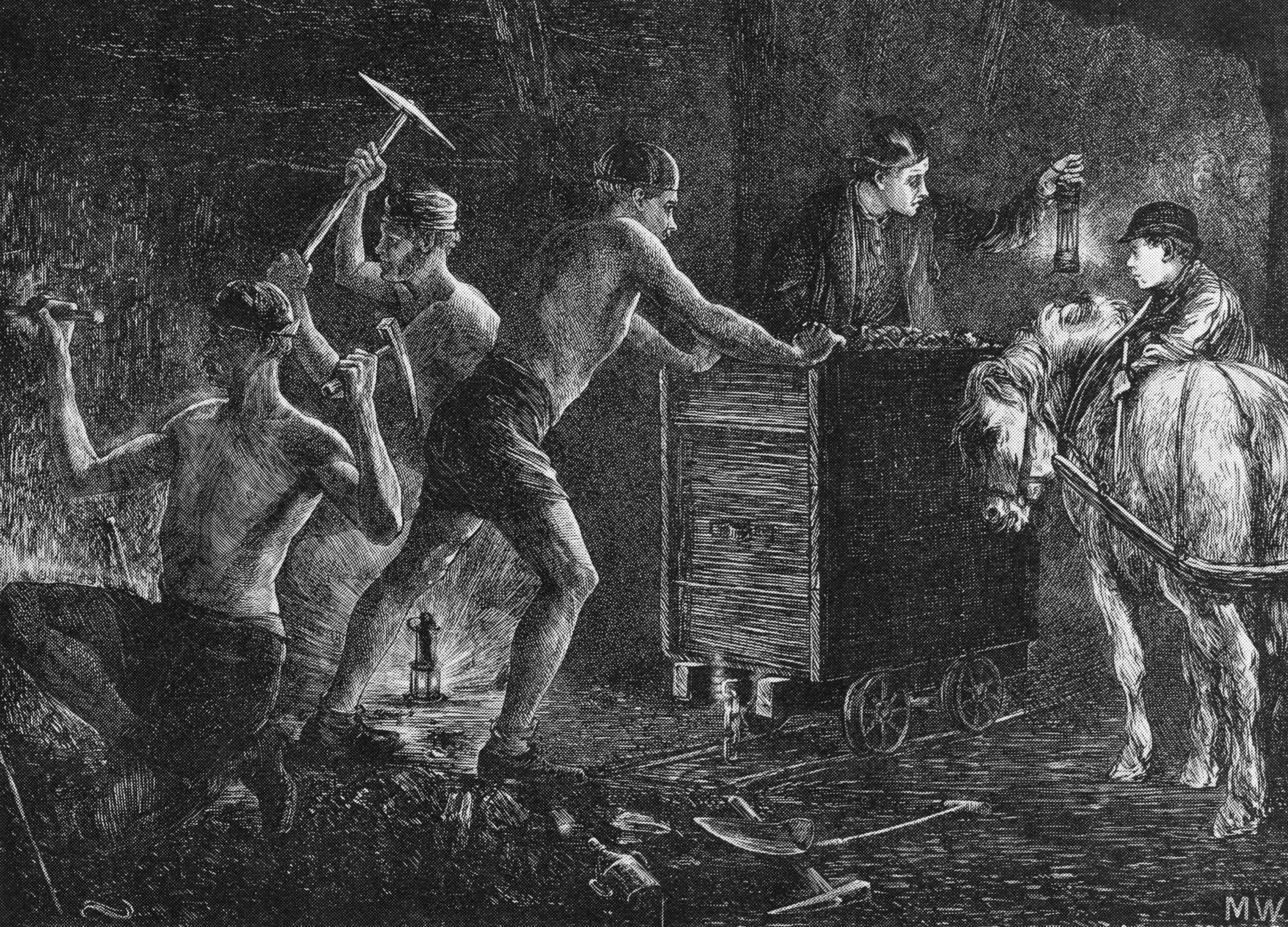

* The VALUE Layer: You say this is a $2B market. But given that TDM is a well hypothesized but still faith based, machine-aided R&D fishing expedition, its difficult for either party to know what the appropriate valuation is for TDM at the start of the process. To use an old world mining metaphor, its almost as if we need 2 separate staged licenses – one for exploration and assay of the data, another for commercial exploitation.

Typically in the mineral world, the value of the fuels is significantly higher than the tools used to discover or extract them – at least in a successful operation. But the world is littered with the refuse of costly dry holes or mines where the yield never outperformed the cost.