I recently served as a reviewer of applicants for a conference scholarship. In that capacity, I reviewed 17 packages of application materials, notably including essays on an assigned topic dealing with the future of libraries.

Most, but not all, of the applicants were relatively young librarians in the early to middle stages of their careers. Because of their relative youth in the profession, I was intrigued to see two themes arising repeatedly enough (and strongly enough) in their essays to be noteworthy. Those themes were:

The just-in-case collection is dead

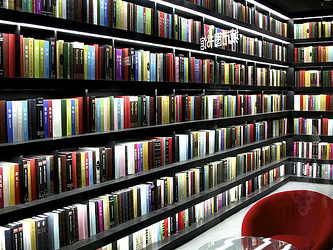

Over and over again these young librarians struck a common note: that the library collection, as traditionally understood, is dead.

It’s worth noting that these writers weren’t saying the print collection is dead, but rather that the very concept of a librarian-built, prediction-based collection, in whatever format, is moribund. Furthermore, none of them seemed to be particularly upset about this; on the contrary, they generally mentioned it more or less in passing and as if it were a self-evident reality and nothing to get worked up about. Interestingly (to me anyway), this is something I’ve been arguing for some time, in one way or another, with frequent and sometimes quite angry pushback from my contemporaries in the profession. I’ve become so used to that pushback that I was truly startled to see how universally this proposition was taken as self-evidently true among this particular group of early- to mid-career librarians.

These young librarians may not be representative of the rising generation generally in terms of their belief about the future of library collections. But if they are, the implications may be significant—both for libraries and for publishers. A librarian-built, just-in-case collection is at the core of the traditional library’s service model and of the value proposition it makes to its sponsoring institution. Historically, virtually all of the library’s practices and service offerings have centered on that kind of collecting and that kind of collection: reference services and bibliographic instruction focused largely (though not exclusively) on helping patrons use the collection; catalogers cataloged the collection; collection-development staff selected materials for the collection, and acquisitions and serials staff ordered and processed those materials. Interlibrary loan, special collections, even IT services were all focused either significantly or exclusively on management of the collection itself and access to it. If the young librarians who wrote these essays are correct, then library employees like me are basically feeding on a carcass.

The necessity of collaboration with vendors in order to bring about our desired future

Not a single applicant spoke of vendors and publishers in an adversarial way — not even those who were most actively and enthusiastically involved in open access and open educational resource initiatives. On the contrary, they talked repeatedly about the need for libraries and traditional publishers to work together in order to bring about the best-possible future for scholarly communication.

I found this a bit startling as well. Every generation seems to believe that the generation coming up behind it is more idealistic and less realistic than it is, but in this case I wonder whether the opposite is true — if my generation of librarians is more utopian in its vision of a scholarly-communication future freed of all restrictions and roadblocks, and the rising generation more realistic and hard-headed about what is and is not likely to be done. Surely it seems hard to imagine a constructive way forward that doesn’t involve some degree of cooperation between libraries and publishers (unless, of course, libraries want to take over the job of publishing entirely themselves, and exclude traditional publishers from the ecosystem — an eventuality that I find seriously unlikely, for a variety of reasons). Yet it seems to me that many librarians see publishers quite simply as the enemy, and regard collaboration with them as “collaboration” in the occupied-country sense rather than the cooperative-colleague sense.

A few thoughts on the implications of these two themes:

First: My subjective impression is that the mindset represented by these young and early-career librarians departs pretty significantly from the one prevalent among librarians who (like me) are 25 or more years into their careers. Among my age/career-length cohort, there is still considerable ambivalence about moving away from traditional collection practices, and even more ambivalence about the prospect of true and meaningful collaboration with publishers and vendors. To be clear, when I say “traditional collection practices” I don’t mean “shifting from print to online.” Most librarians my age and older have accepted that shift, with varying degrees of good grace, and especially where journal content is concerned. (The jury is still out, and fighting, over the right balance of print to online when it comes to books.) What we remain very ambivalent about is the right balance of librarian-driven and patron-driven collection building, whatever the format, and about the appropriateness of working cooperatively with publishers. I was, again, startled by the degree to which the essays from these young librarians suggested that their generation feels little if any ambivalence about either of those issues. To them, the collections question may be settled — and it’s settled one the side of just-in-time rather than just-in-case — and it seems to be completely self-evident that libraries should see publishers as collaborative partners in the future.

Second: regarding library collections in particular, it’s worth noting that these writers were not just saying that traditional collection practices are dead; they were saying that the concept of the just-in-case collection itself is dead. They may be right, and they may be wrong — but their near-unanimity in this view strikes me as significant. Assuming this group of scholarship applicants is at least broadly representative of the rest of its generational cohort, we have a rising generation of librarians who seem to believe that this core function of the library is dead. If they do (and it seems like a more rigorous study would be in order to determine whether that’s the case), it portends seismic changes to the library profession — regardless of whether these librarians are correct or incorrect in their assessment of the declining importance of traditional collecting. To the degree that publishers depend for their revenues on libraries building traditional collections, the implications for publishers are obvious and just as important.

Third: as for library-publisher collaboration, these young essayists embolden me to say that maybe it’s high time we librarians acknowledged and dealt with the fact that the faculty we serve are also the publishers we revile. (And yes, yes, I know we’re more than just “servants” of the faculty, especially those of us who have faculty status ourselves. But we ignore the service component of our work at our peril. That’s a subject for a whole other column.) Too often, we say “publisher” when what we mean are for-profit commercial publishers, ignoring the fact that the great majority of scholarly publishers are nonprofit scholarly and scientific societies whose members — our faculty — derive direct and concrete benefit from the access tolls imposed on their publications. This is not a simple issue, of course: some putatively nonprofit publishers are in fact highly profitable, and some putatively mission-driven societies use their content monopolies in ways that are questionable at best. (Of course, even libraries have a tendency to impose inexcusable access barriers.) But this complexity is precisely the point: a Manichean worldview is not helpful in an ecosystem as complicated as that of scholarly communication. What these young librarians expressed in their essays tends to reflect that complexity better than much of the rhetoric I currently hear from older, more experienced, and — let’s just say it — more entrenched librarians. Those, that is to say, who look a bit more like me.

It kind of gives me hope for the future.

Discussion

48 Thoughts on "The Death of the Collection and the Necessity of Library-Publisher Collaboration: Young Librarians on the Future of Libraries"

I trust the young librarians were referring to regular collections, not special collections. Presumably it is the latter, much more than the former, that give a library’s collection its “special” nature, not duplicated elsewhere.

The attitude of these librarians reflects the attitude of faculty themselves about building personal collections. Back in my day in graduate school (late 1960s) faculty still often tried to buy all the books essential for their fields, especially in fields like classics and philosophy where the number of new books to be purchased was still manageable and everyone more or less expected to own editions of all the classic authors from Plato on. This aspiration had disappeared by the 1990s, as I discovered when conducting a survey back then. It is the rare faculty member now who strives to have a personal library of that magnitude–and that change goes some distance toward explaining the decline in monograph sales beginning in the 1980s.

How does just-in-time work for journals, or is it confined to books?

Libraries have purchased articles on demand for patrons for decades. In recent years, more programmatic solutions like GetItNow and ReadCube have emerged. For a discussion of one library’s adoption of ReadCube, see this article.

Understood, but the question is what does JIT look like, in full flower as it were? At one extreme there would be no subscriptions. Or one might just subscribe to a core set of journals that faculty say they read regularly, then JIT the rest. In any case it sounds like under JIT the big deal is dead. Do you agree?

If you’re talking about 100% article-based purchasing with no subscriptions, then yes, obviously it would mean the end of the big deal because it would mean the end of the subscription model, period. To me, this is actually the only rational way to acquire journal content; paying up front for a year’s worth of articles without knowing how many will be good or which ones will actually be needed makes no sense to me. But the existing system has tremendous inertia behind it, and it remains to be seen to what degree it will be supplanted by a new and more sensible one, and how long it will take for it to happen.

Whether it is perceived as better to pay up-front for a big deal or just-in-time depends on what measure is used to determine this. Cost per download is the standard measurement. Extending this to books presumably means cost per *chapter* download.

Since a fully just-in-time system requires brokers like ReadCube, who are going to be financed by the major publishers anyway, the line between the big deal and just-in-time is inevitably blurry.

Cost per download isn’t a perfect measure. For example, repeated downloading by the same user of the same content all counts as new use, which might not be meaningful. But while working in collection development, I assume that Elsevier, Springer, and Wiley all watch this measure carefully for their own content.

Agreed that cost per download isn’t a perfect measure, and in fact I’d go further: it’s also not necessarily a reliable measure. As long as we count on publishers to define “download” or “use” and to tell us what those numbers are, I regard the data with some skepticism — publishers have a serious conflict of interest in reporting usage. We need those data points, but we also need to read them critically.

I disagree, though, that the line between the big deal and JIT is inevitably blurry. I would contend that the big deal and JIT are, in fact, exact opposites of each other.

Thanks for this post Rick. I’m a little late to the party but I related particularly to your comment:

As long as we count on publishers to define “download” or “use” and to tell us what those numbers are, I regard the data with some skepticism

I’m seeing use stats in one report at this library that reflect as little use as a 10 second ‘peek’ at an e-book title and wonder what should be counted, or omitted, by some vendors. Perhaps such an online glance is more of a ‘rejection’ stat (as in ‘no I don’t want to use that title now thanks’)?

I am not too sure publishers count on library book sales too much anymore. STEM publishers print about 300 copies for world wide sales and then go to POD for the rest of the sales for the life of the book.

I think the collection building status depends on the specific library and the philosophy of the University Librarian. There are many great libraries in the US that still follow a just in case collection strategy and they have a collection development staff that are proactive and highly competent. Great libraries like NYPL, Columbia, NYU, the University of Texas at Austin, UCLA, Berkeley, University of Washington, and I am sure others still are building collections to serve their students and faculty. The question is more for the future when the collection development staff begin to retire and either not replaced or the next generation is not so highly trained or motivated.I have know so many bibliographers who have build their collections with skill and precision but perhaps they are a dying breed as the next generation is simply not interested in continuing that dedication to collection building. So collection building is not dead yet, but in 5 or 10 years it could see a serious decline.

This is very interesting. If it’s not giving away too much, could you please mention what these librarians believe is to take the place of “the collection”? Is it just a matter of different types of outsourcing, such as allowing the vendors to do the selection for you, or relying on patron-driven-acquisitions? Or is it something different?

I think it’s instructive to look at the information environment in which young professionals have grown up: it’s not one in which you typically stockpile a bunch of books or music or movies, but rather access them from the cloud whenever you want them. Imagine yourself in the shoes of a 25-year old starting his first library job: he comes into a building that is filled with printed books that, in all likelihood, are being used less and less each year, and that also provides online access to journals and a quickly-increasing number of ebooks. He looks back at the information world in which he grew up, and then looks around him at the library in which he now works, and he almost certainly sees an institution that is slowly coming to terms with a completely new information environment and gradually moving in the direction of a cloud-based, just-in-time program of information access.

He may be right and he may be wrong, of course; and if he’s right, that evolution may turn out to be a better thing or a worse thing, on balance, for scholarship. But I think this is what the young writers whose essays I read are seeing now and expecting for the future.

I personally have little problem with the idea of the death of the physical collection. I use printed books less and less myself, and while my apartment is full of books, I have no doubt that someday, all of the scans in Google Books will be available to everyone, plus every new book that appears. That would be great. It could be happening now, except for the decision of a single judge. If his decision had been different, we would all be living in another world. Publishers cannot avoid such a world forever. That time is inevitable I think.

My problem is that no matter what, it seems to me that there will still be a “collection” although it may be scattered thoughout the Internet. From everything I read, people are unanimous that they have serious problems with “information glut” and “information overload”. I know I have serious problems. This means that people really want and need some kind of selection from all of that growing mass. And if there is a selection, then that–at least to me–means a collection. That’s what libraries have always been after all: bigger or smaller selections from the mass of printed/physical “whatevers”.

If this is accepted, then the questions become: how do we manage this selection/collection and who will do it? We might decide that managing all of it will be completely automated, from selection to paying, to organizing and describing/automatic indexing (ala Google). It may be crowdsourced. Or there could be various hybrid systems with librarian oversight.

But this still supposes a type of selection from the whole, and that is a library’s collection. Each selection should be based on the needs of the community it serves (whatever that community may be). Different communities would have different selections of course, just as they do now.

Would you really be confident that we could trust Google with stewardship of the entire world’s collection of literature? The problem with the proposed Google Books settlement was that it gave Google monopoly control over so much material. Given Google’s duty to shareholders, I would have a hard time turning over the control of the world’s libraries to them, particularly since they’ve been known to regularly drop unprofitable projects, not to mention the roles they play in spying on users and censoring content.

This is getting off the topic of the original post, but I don’t think it was a matter of “trusting” Google. The monopoly Google supposedly had was not really a monopoly at all. They had paid for scanning zillions of books and consequently, they owned those scans. While you could say that they had a “monopoly” of what they had created, others could say they owned what they created. That is not so controversial.

The question was: should Google be allowed to share those scans with the public? They had worked out a method where everyone would get paid: Google, publishers and authors, while primary access would be through the libraries. Many authors freaked out for reasons I still cannot fathom; a lot of them seemed simply to want all the scans deleted and Google Books shut down. The judge decided that the project had to be opt-IN, instead of opt-OUT as it is on the regular web. An opt-in system on the web would make Google and every other search engine illegal but this precedent was not followed for Google Books. Google decided not to appeal.

Nevertheless, people still want these materials electronically and sooner or later, somebody will make sure they get them. The final result is that publishers and libraries are now living on borrowed time–time that neither has used very wisely–while the public lost access to one of the greatest research libraries that has ever existed.

But there was never a danger of “turning over the control” of the world’s literature to Google. The libraries would continue to exist. The physical materials scanned by Google are still in those libraries and if necessary, it could be done again, although to do so would be a tremendous waste of money, time and labor. There has been such animus in some quarters against the Google Books project, it may actually need to be done again.

As I recall, the monopoly issue came about due to the legality of the use of orphan works. If I recall correctly, Google would be given the right to exploit orphan works unless the original copyright holder opted out. That right would be exclusive, because only Google was a party to the settlement. For someone else to get that same right, they would have to scan the same works again, essentially duplicating the efforts of Google and the libraries, then get someone to sue them, then get that suit turned into a class action lawsuit, then negotiate that same settlement. Hence, essentially the settlement gave Google a monopoly because those things were unlikely to happen. Had it instead put the works in the public domain, or required Google to share those scans with others in return for profiting from them, it would have been a much more acceptable settlement.

The judge decided that the project had to be opt-IN, instead of opt-OUT as it is on the regular web. An opt-in system on the web would make Google and every other search engine illegal but this precedent was not followed for Google Books.

But to be fair, Google does not share the full text of copyrighted websites with the public. They only offer snippets and that was not what was proposed here, rather the plan was to make the full, copyrighted text available (and only available through Google).

I share David’s concerns, particularly with regard to Google. I’m tremendously grateful for what Google has done and continues to do, but I have no confidence in it as a permanent and sole source of access to books.

James: it sounds like you are talking about personal collections. Under JIT I assume these are paid for by the library, for the faculty members. Discovery is a different issue.

James: it sounds like you are talking about personal collections. Under JIT I assume these are paid for by the library, for the faculty members. Discovery is a different issue.

No, I mean everything. With the Google Books project, the idea was just as you mentioned: that all the scans would be available to everyone through paid access, mostly paid through their local libraries. Assuming that these materials will never be made available electronically doesn’t make sense because people will be demanding it more and more.

To me, this is just like any other library, except the number of materials available grows exponentially, and actually equalizes access in many ways–one library will not have access to a significantly greater number of materials than anybody else.

Certainly, the idea of library’s collection will change and how people will find out what is in the collection will also change, but I think library collections are under no threat, and may perhaps become much more important than they are today.

I can make a guess as to which scholarship this was and so would put forth that some of the perspective that you see in the essays is potentially reflective of the essay prompt. Whether I’m correct or not in my guess is not as important as my request … which is – would you share the prompt? Given its framing, one might not expect to see a different perspective and would help assess whether the themes you observe are an effect of who writes to a prompt framed a certain way?

As a young-ish librarian myself, I reject the position that library collections are dead.

Let’s look at the alternatives: subscriptions, print-on-demand, patron-driven-acquisitions, interlibrary loan, or big e-book bundled packages. I’ll deal with each briefly.

Subscriptions and bundled packages essentially outsource the library’s collections to the publishers/vendors. This is great if you think you really need all of those OUP and Springer biology books from 2013 at your library, but I am pretty sure we don’t. Bundled packages also incentivize publishers to pad the packages with less substantial content (same principle as journal big deals) and bundle it in with substantial content.

Patron driven acquisitions is still very much an open question. Publishers are starting to raise their STLs or even eliminate them altogether. Whether the major publishers are even going to continue allowing PDA to siphon off their revenue from sales is very uncertain. How could a library rely on this completely to predict what a collection will look like in ten years? Nothing more than a supplementary acquisitions stream, unless it becomes a lot more established than it currently is.

ILL and regional repositories are great but the loan periods are shorter, restricting grad students to a shorter borrowing time. It also doesn’t draw on the benefits of serendipitous discovery, unless a library or library system is really savvy about how to make this happen online. Most I’ve seen are not.

Print on demand is a dead letter until it garners a critical mass of publishers to work with the Espresso Book machine. Period.

All of these options are good for some things, not so hot for other things, and each one would be a slender foundation to build a library’s future on. To be understated about the issue. Obviously I’m not disparaging any of these tools for what they bring to our profession.

If so many librarians are eager to turn their collections over to publishers and vendors, maybe they should ask themselves how well that worked out when it came to journals.

Thanks, Josh — it’s certainly good to hear from a variety of perspectives on these issues. One point of fact, though:

Print on demand is a dead letter until it garners a critical mass of publishers to work with the Espresso Book machine. Period.

Actually, POD is already a very important part of the book-fulfillment system for libraries, and has been for years. It’s just that most of it is still happening at the jobber rather than in the library. Ingram, for example, has a huge POD operation, and the last time I checked they were boasting the ability to print and ship a book at 2:00 pm if they receive the order by 10:00 am. That’s obviously not the same thing as immediate fulfillment (which is what the EBM would offer if it worked better), but it means that POD is far from a dead letter. It’s not even the future–it’s already greatly affecting libraries’ ability to provide books at or close to the point of need rather than trying to guess ahead of time what will be needed.

That’s true, Rick. POD provided by jobbers is not something I would knock. And I do REALLY like the idea of the EBM, and I hope it becomes a reality for all libraries. Just don’t think we’re there yet.

I’d just like to raise a tiny point of clarification: could we please refer to new librarians, instead of young librarians? I share many of the perspectives and values as those conveyed in this post, and am indeed new to the profession. But I can by no means be described as young, and thus feel somewhat excluded from this discussion. New is a much more inclusive term.

I appreciate your point, Elizabeth, but I think in this particular case the actual age of the respondents is relevant. (In the piece I referred to them as “Most(ly), but not all… relatively young librarians in the early to middle stages of their careers.”) Part of my point is that the generation of which they’re a part comes to the library profession with a very different set of assumptions and experiences than folks my age did, 25 years ago — and that’s a somewhat separate issue from how long they’ve been librarians, though that’s relevant too.

All of that said, I hope you’ll feel completely free to contribute to this conversation regardless of your age or career stage. The fact that we’re discussing a group of people who mostly come from a particular generational cohort by no means excludes those from other cohorts from the conversation.

Interestingly, JIT may be far more labor intensive for the library than collection building. For example, the big deal is wholesaling personified. But buying individual articles and books for individual faculty is retailing. Automation helps but even Amazon as a huge customer relations operation. JIT may build staff.

It depends entirely on the mechanism involved. Products like ReadCube and SIPX involve little or no real-time intermediation by the library. It’s in the very nature of most PDA book programs that they involve no title-level “selection” at all, on either the patron’s or the librarians part. Other kinds of behind-the-scenes work are involved in the program setup and maintenance, of course, but it’s not anything like retail-level book acquisition.

Now I am more confused than ever. I thought the T in JIT was the time that the patron expressed a need for the item. Perhaps JIT is not yet a well defined concept. In time for what, I wonder?

Budgeting is also an interesting issue. In collection mode one works to a defined budget. JIT suggests that an unpredictable cost amount may arise, requiring some form of dynamic rationing. This in turn means dealing with those patrons that are denied. Sorry to be a pest but designing systems like this is a field of mine. I call it paperwork engineering. JIT seems considerably more complex than collecting.

David, the reason you’re confused is that you don’t have enough background information on this topic to be able to ask well-informed questions. You’re clearly not familiar with how DDA works, either for books or for journal content, nor do you know how libraries work. There’s no shame in this; your fields of expertise lie elsewhere. But this probably isn’t the right forum for the kind of remedial instruction in scholarly communication and library management that would be required to bring you up to speed.

No Rick, I am pretty sure that JIT is a confused concept at this point, as far as the future of libraries is concerned. As you said, everything depends on the mechanism, but there is no specific mechanism at this point. This is the normal confusion that accompanies technological revolutions, one I first described in 1973. How libraries operate today is irrelevant because, as you point out, we are talking about a fundamentally different form of operation. My observation is that what this form is has yet to be determined, but various experiments are in progress. This is actually the result I expected, when I began my probe.

No Rick, I am pretty sure that JIT is a confused concept at this point, as far as the future of libraries is concerned.

You’re mistaken about that. There really isn’t any confusion about this concept — at least as it applies in libraries — among those of us who are doing the work on a daily basis. There’s disagreement about the degree to which the various JIT strategies are appropriate and about which mechanisms work best in various situations, but disagreement and confusion are not the same thing.

As you said, everything depends on the mechanism, but there is no specific mechanism at this point.

I didn’t say that everything depends on the mechanism, and there are many specific mechanisms in place and functioning at this point.

If you’d like to discuss this further, maybe we should take it offline. Feel free to email me at rick.anderson@utah.edu.

Are you aware of the CCC’s “Get It Now” program, which was designed to provide much faster access to journal articles than is normally available through regular ILL systems? It has proven quite successful and , rather than increase labor demands, decreases them.

“the need for libraries and traditional publishers to work together” … seems to be a forlorn hope.in view of the fact that most for-profit publishers have a take it or leave it attitude towards libraries.

This has been a really interesting conversation thread. Libraries and publishers have always, through the print era and to a degree in the digital era, had a symbiotic relationship – each needing the other. The core purpose of both is about content (through changing business and access models) and delivery. This is a fluid and dynamic mix still being sorted out, whether through JIT or PDA, or OA or other emerging direct or customised services. Agility in this context is key.

However, what interests me in terms of the ‘death of the collection’ is the other traditional role of the library (apart from providing access) which is preserver/repository (or whatever) of content, of knowledge. In the print era libraries were, as public services, the de facto archive of and for publishers and managed access to the physical collections. In the digital era Google, the Internet Archive or some individual publishers are taking that role, assisted in varying ways by the HathiTrust, Portico and some national library initiatives. This is ‘collection’ on a more global scale and the is backdrop of the profession for new librarians and their attitudes towards collections.

The shift of content/knowledge delivery through libraries from a public service to a corporate (albeit partly publicly subsidised) service is now pretty much I think a given. How this pans out in the long term *control* of that content (and long term preservation and access) should be more of a concern for new librarians entering the profession.

I find it interesting, and slightly depressing, that no one in the thread of comments so far seems to have picked up on two crucial words in Lynne Rienner’s post two days ago: the words “world-wide”.

This, in full, is what she said:

“Whoa … let’s not write off the importance of book sales to libraries just yet. We publish monographs (among other things) in the social sciences, and we count on selling (and do sell) considerably more than 300 copies world-wide. Library sales are the backbone of our business.”

It would be great if commentators in the US could remember that academic and professional libraries and librarians outside N. America do not all think (and have collection building strategies) that reflect the concensus of current American librarians’ thinking as presented in this stream of comments. I speak as a Director of Eurospan Group (London) which markets, sells and distributes academic and professional books from over 100 American specialist publishers (including Lynne Rienner’s titles), and our sales of their print format books to libraries outside N. America are healthy, and, in many parts of the world, rising year on year.

These are good comments, Stephen. It would be very interesting to know whether the views expressed by the cohort of librarians in the group I encountered — all of them American — are similar to those held by British, or continental European, or Asian, or African librarians of the same age and/or career stage.

Any kind of collection development for books, whether on demand or prediction built, will run up against a student’s “I need it now.” I have spent much time finding books with a student who will then tell me “I can’t wait for interlibrary loan because the assignment is due in the morning.” As librarians we will always need to have a book in reserve, ready to hand to the student. With this in mind a prediction built collection should become what the students need.

Isn’t it a given that JIT collection development allows for librarian initiated purchase of reserve books for classes and other obviously essential new editions of heavily used books? I try to avoid setting policy on the basis of exceptions (students waiting until the last minute).

Yes — I’m not aware of any library that either operates on a 100% patron-driven/JIT basis, or of any that is planning to do so. The discussion is usually around what should be the proper balance between patron- and librarian-driven acquisition, and between just-in-case and just-in-time. And the answer will depend to a significant extent on the mission of your library and the nature of the institution you serve.