The underlying economic assumption of the movement for open access monographs is that provosts will pay for what librarians will not. Never mind that libraries get their funding through the provost’s office; what matters is the shell game: move the money around and somehow or other it will grow in size. And if it does indeed grow, what’s not to like?

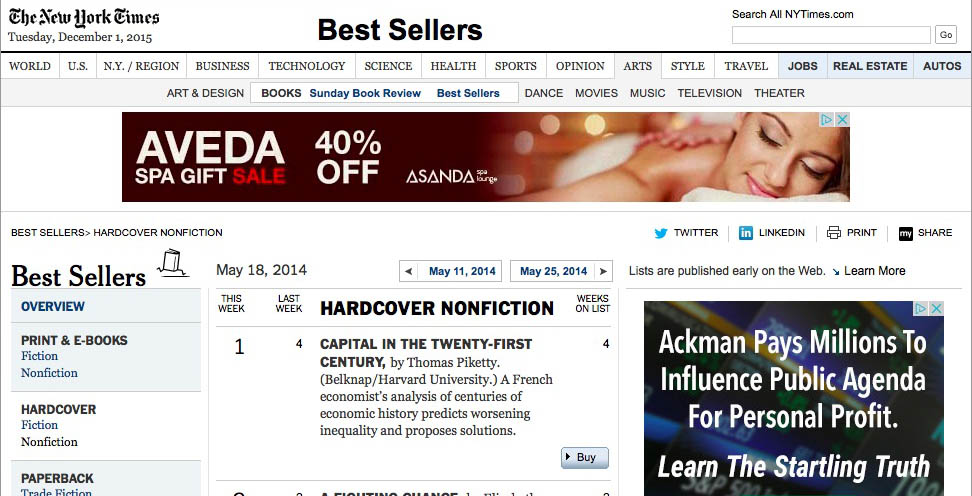

Here is how this works. If we go back a couple decades, we had a university press world that was partly supported by sales to libraries. Over the years the percentage of press books purchased by libraries has dropped. About 5 years ago I did a survey and estimated that about 25% of university press sales went to libraries, down from about double that 20 years ago. (About an equal number found their way into college classrooms.) There is a problem with this survey, namely, that we can’t know for sure how many press books find their way to libraries because virtually all sales are on an indirect basis, with an assortment of middlemen sitting in the value chain between publishers and libraries. On the other hand, I was able to get in touch with some of the distributors and got some off-the-record information. The decline of press sales to libraries is well-documented but not definitively and publicly documented.

There is a lot of hand-wringing over this information. Aren’t libraries falling down on their job if they are not building comprehensive collections of university press books? Why the bias in favor of STM fields and STM journals in particular, when university presses concentrate mostly on books in the humanities? Isn’t the library supposed to support all of a university’s activity, not only those fields that have heavy support from funding agencies and governments? It’s just not fair!

And maybe it isn’t. In my view, though, libraries are doing their job and doing it well. Libraries are not buying STM journals over university press books because of a bias toward the sciences (scratch a librarian and you are more likely to find an English major than a particle physicist), but they do have a bias, and that bias is to the actual usage of their collections. With the usage of STM journals recording big numbers and many university press books circulating rarely or not at all, the bias is built into the data: the best collection is the most useful collection. This does not mean that monographs don’t circulate or that they have no or little scholarly value; rather the point is that with finite resources, librarians have to make tough decisions. It’s a very difficult thing to be on the wrong side of a tough decision.

Let’s imagine an alternate universe where monographs are in great demand. A librarian reviews the usage statistics for books from the university presses of Kansas, Colorado, Toronto, MIT, and Rutgers and notes that the books circulate so often that the library has to purchase multiple copies or renegotiate its agreement for ebooks and short-term rentals. Meanwhile, the librarian’s colleague notes that no one reads Nature or The Lancet any more. Do the librarians conclude that the library’s patrons are simply wrong? Do they fail to acquire university press books because the institution wants to look better in STM? Of course not. Libraries acquire what people use. The problem that monographs have is that their demand is simply not as great as that for STM journals. Thus fewer books are acquired. It’s a cruel thing to say, but the market has spoken. For my part, I don’t know any librarians who would not acquire more books if resources or demand were greater.

The problem that emerges from this situation — in which librarians are doing their job and doing it well — is that the monograph publishers find it increasingly difficult to continue to publish monographs. Those monographs serve not only as a form of scholarly communications (in which they make a tepid contribution if they are not read by an audience sufficient to support the books financially) but also as a means of certification. Without a published monograph, scholars in many fields at some institutions would find it hard to have successful tenure and promotion reviews.

Enter the open access monograph. As a rule, open access is not so much an innovation as it is a capitulation — a capitulation, that is, in that it recognizes that the marketplace sets a high bar. There may be insufficient demand to read a particular monograph, but the demand to publish that book is enormous, beginning with the author and extending to friends and colleagues. Inasmuch as the funding for monographs and the research underlying them is small and often nonexistent, authors naturally look for help in paying the fees for Gold open access. Thus the provost is brought into the discussion. If the provost can be persuaded to pay for publication (for a book that is fully peer-reviewed and deemed to be outstanding from a scholarly point of view), then everybody is happy. The author finds a publisher; the publisher speaks with the authority of the university with which it is affiliated; tenure and promotion committees have third-party validation of an author’s work; and interested parties (all of whom are assumed to be impecunious) can read the book at no cost to them.

It will be immediately observed that there is an easier way to make these books available. Institutions could increase library budgets and they could increase their support of their presses. But those options are not on the table. So now the provost, having declined to step into the library’s operations or the local press’s funding, begins to make large grants to guarantee that members of the faculty find an outlet for their work.

Where will this additional money come from? It seems not improbable that it will start with newly budgeted sums. The real test of this model is what happens over time. An economic recession (not even open access can do away with recessions) could make money tight on campus. Will the local press be asked to provide some of the funding for the Gold open access fund? Is there an inexhaustible supply of external funders? Will some departments on campus argue that the money going toward open access monographs would be better spent on graduate students in life sciences? In flush times these conflicts are small; in bad times people behave badly.

What is so ironic about this is that open access in theory is about providing access to people who don’t otherwise have access. But the problem with monographs is not that people don’t have access but that there has been insufficient demand for libraries to ensure that all monographs are represented in their collections. A book that circulates once in ten years does not make a strong case for opening up access further. The problem is demand, not access. Gold open access for monographs is solving for the wrong problem.

Meanwhile, we might ask where all these newly tenured faculty will be teaching. If there is a crisis in credentialing, that must mean that there are open positions waiting for certified people to come along. I personally am not aware that there is a plethora of job openings waiting for university presses to send qualified candidates. Perhaps this is the underlying reason behind the weak demand for monographs. This is not something publishers can solve.

While the open access situation plays out, university presses will continue to do what they have long done: publish important books for the scholarly communities they serve. The monograph world is mature, but it is not going away. The university press sector is doing far better than the common perception. Of course, some presses are doing better than others, and there is a reason for this: they are better publishers. They are better in identifying outstanding authors, in matching a book to its potential readership, and in promoting the heck out of it. This is another way of saying that they live and thrive within an environment of demand, capitulating to no one.

Discussion

40 Thoughts on "For Open Access Monographs, Peter Pays Paul. Who Pays Peter?"

Joe, your questions about OA monograph funding are good but not insuperable ones. As you know the issues have been explored and deepened in two recent Mellon-funded reports looking at how a producer-pays funding system for monographs would work at Emory University (https://pid.emory.edu/ark:/25593/q4fd0) and Indiana University / University of Michigan (http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/113671). Irrespective of where the funding would come from within the university (probably multiple sources), an important thing to remember is that the total cost of funding all humanities books from even a highly productive research university like Michigan would likely not exceed $1m a year and would be much less for smaller institutions. $1m is about the start-up funding for a single new hire in Chemistry but would have the consequence of making 50 humanities faculty very happy — a bargain that any Provost would be attracted to. There are clearly many questions to be resolved (how can one avoid disenfranchizing poorer institutions, non-tenured faculty, small commercial publishers, etc.) but they are ones worth addressing if we believe that the books university presses publish have potential beyond a narrow group of scholarly readers.

Charles, I love your optimism, but I see little evidence that making humanities faculty happy is of much interest to provosts–certainly not interest enough to fund the level of ongoing investment it would take. I think that sea changed about the time Larry Summers was at Harvard saying the humanities are a lost cause.

I agree that this may not be about access, or not entirely. But the marketplace of scholarship is much larger than the marketplace of readership. So, for example, a University might want to underwrite a bunch of monographs, in an ongoing way, to showcase its scholarly strengths. A lot of good stuff might get published under this model.

At most research universities the humanities and social science departments struggle for resources in a very competitive environment with the STM departments. Funding for monographs even in the library continues to shrink. Extra funding for open access monographs is a very hard sell. Few provosts ever get down to that microlevel. The individual academic department if not the faculty member bears the responsibility to find their own funding. I don’t see a ground swell of support for open access monographs. A number of small or medium size STM publishers are evaluating their monograph publishing programs. If the STM publishers cannot support monographs, I don’t see much hope for the humanities and social science publishers.

Lets see. I just read the white paper and they forgot one of the costly parts of publishing: Marketing.

What I see here is a $1,000,000 per year job program for some 40 profs in the humanities who are at a given university. After all at $25K per title that is some 40 titles.

Prof A writes a history book. “A” then shops the title to those publishers who are known to publish in that area. They all reject the title. “A” then goes to his/her university and low and behold gets a contract.

So what we have is a university funding 40 profs to publish something no one really wants to read. Thus, the lack of marketing dollars is accounted for.

But, we have assured those anointed few a job for life. Not bad if you are among the washed!

Hi Harvey – my thoughts exactly, and indeed I discussed this recently with Don Waters at Mellon. I know publishers who will spend $20k per title on marketing alone – this gets readers for those titles, but many publishing marketers will acknowledge that tracking the ROI of their spend is difficult i.e. they don’t really know which of their efforts actually brought those readers in. While there are those to whom marketing is a dirty word (implying cold calls, ethically dubious advertising techniques, etc), we must recognize that there is value in raising awareness of publications among the audiences they are intended to serve. I think (and suggested to Don!) that we need a study on what works when it comes to marketing publications (perhaps particularly, in this case, monographs). Otherwise, as you say, we have excellent studies for some aspects of the costs of monograph publishing, but we’re missing data about some of the real-world costs involved.

It seems to me that judging the ROI of marketing investments is especially difficult when you’re producing books that are being made available at no charge to readers. What form does “return” take when your marketing efforts result in no revenue? (Unless the marketing is being directed at potential authors, of course.)

Rick:

I guess the marketing is for the funders. After all they want to know what you are doing. I would bet the library has a nice presentation each year for the administration that justifies their budget request.

One form of ROI is book prizes. I made it winning top scholarly book awards a priority at Penn State. Before I came in 1989, the Press had won a total of 4 prizes since its founding in 1956. By the time I retired in 2009 the Press had won over 100 book prizes including the top prizes awarded by many associations like the Latin American Studies Association and the Middle East Studies Association. Marketing certainly plays a role in getting books so recognized. Indeed, it is one function of the marketing department to submit books for appropriate prizes.

Book prizes are not an aspect of ROI. ROI is a financial term. Let’s not get overly metaphorical. Book prizes may be much more important than financial returns, but we should not add apples and oranges.

True, Joe, and I was mostly using the term metaphorically. But there is a real financial dimension here, too, as book prizes generally lead to increased sales.

The driver for creating many monographs(and of course there are many where this is not true), as you say, is the career of the author, not the benefit of the reader. We could even suggest for some, a reader is a by product.

In this sense, is the monograph that far removed from the PHD thesis? Again, written for the author’s phd, not primarily for the reader. And the thesis is paid for by the author (or proxy, ie government) in fees, not by the reader, it is free, whether online or in a library basement.

So does it not make sense that as it is the author who benefits and ‘demands’ the creating of the book, is the one to pay.

This also makes a better market. if there are x academics wanting to publish and able to pay, then x books can be published, rather than x academics able and willing but publishers/libraries only will to cater to a subset due to less demand.

There’s a secondary point here, if it is recognized from the start that a book will likely have a very low readership, does it need the same level of editing, formatting, proofing and marketing as a book which has potential for a larger readership (note, peer review still the same). Again, the PHD thesis will typically have very limited input from those other than the author in this sense.

Chris

Joe gets at part of the truth but not all of it. As some others have suggested, he overlooks the imbalance of political power in universities. Those who bring in the vast majority of research grants, viz., the science faculty, get to call the shots about how university funds are allocated. It doesn’t matter that most librarians have been trained in the humanities or social sciences. The second point Joe overlooks is the argument made by Paul Courant, head librarian at Michigan (who used to be provost there and is an economist): he pointed out that universities spend a lot of money on faculty over the course of their full careers, and that adding to the grants that are already given to tenure-track and tenured faculty by the universities to cover the cost of a monograph or two pales in comparison with the overall lifetime investment universities make in their faculty. And adding to this already existing funding requires no new bureaucratic mechanism, unlike schemes like Knowledge Unlatched and Luminos. It is no accident that Courant was a leader of the group that got the AAU on board with its funding of first books. A third point is that there are other ways to fund open access that do not involve title by title funding: consider the example of Amherst College Press, whose funding is paid for by endowment funds, not individual title fees. Fourth, market demand is not the only test of a monograph’s value, as Joe seems to think: what is more important is who reads the monograph, not how many people read it. Scholarship advances by the influence one work of scholarship has on other scholars, and only a few of them need to be influenced in order for a field to advance. Part of the problem of university press publishing for decades has been its reliance on market potential in making decisions about what gets published. That is a distortion of a press’s mission, not the goal of it. Consider what happened when some presses started picking up the mid-list trade books abandoned by commercial publishers and cutting back on monograph publishing. That was the wrong direction for presses to go, but understandable because of the financial presses presses were under. Joe seems to be obsessed with the market as a criterion of success in academic publishing. The short answer is that it shouldn’t be even if it currently is.

P.S. Courant’s argument, of course, only works for tenure-track faculty. Adjuncts and others are left out.

Sandy:

If we look at Indiana Univ there are some 1,357 full time tenured and tenure track profs of which 216 are in the sciences. If we eliminate the school of business and the school of public, environmental affairs, the school of journalism and the school of education we would lose about another 350 faculty. Thus, we are talking about some 781 folks in the humanities. Of the 1357 some 366 are on a tenure track. Is it the role of the University to assure that those in the humanities get tenure because that is what IU would be doing for that select group if it becomes the publishing arm for the humanities faculty! In essence, IU is becoming a vanity press for its humanities faculty.

Even if we expand the role of IU as a publisher and that is what it now is having put the press under the auspices of the library, to include all of the faculty, it would still be publishing what others deemed not worthy for either commercial reasons or other ones.

I still tend to think that good and important ideas are disseminated in society and that if a university press fails in that mission so be it.

Lastly, one of the ways a university evaluates its bet on a new faculty is via the tenure process. If a book is needed to get tenure then the author has to have something to say that others view as worthy. This comes out in reviews. It is not economics or consumer acceptance that determines the worth but other scholars. Then the publisher makes a decision and will price to meet a margin. The commercial publishers do this all the time. Why can’t most university presses?

Who said that a university has to publish its own faculty? (In fact, though, the University of California Press got its start that way, and people like Kathleen Fitzgerald have recently argued for a return to that service model.) The Amherst College Press publishes open-access monographs in the humanities for faculty from everywhere, so IU faculty could publish there. Your assumption that because a press reports to a library that it therefore just publishes for its own university faculty is not true: the press I headed at Penn State became a unit of the library in 2005 and continued to publish for faculty everywhere just as it always had. When a press publishes as a unit of the library, it still uses the traditional peer-review process. We turned down plenty of manuscripts submitted by Penn State faculty. I don’t see where you are going with these comments because they don;t reflect what actually has been happening.

Sandy: I believe the model suggested of IU publishing only IU comes from Joe’s discussion. Also, I believe that the intention of IU is to only publish its own faculty. Why support someone else?

I made no comment about you whatsoever. I know nothing about its programs and policies. My post had nothing to do with any of the matters under discussion in the comments.

Joe: I was only using IU as a hypothetical example. I did not mean to imply that this is what they are doing.

University Presses have traditionally NOT sought to publish works by authors at their host institution. Though this was seen as a key role in their development in the 19th century, it was abandoned as publication began to play a more prominent role in promotion and tenure. Once P&T was involved, the UP publishing scholarship from its host institution was seen as a possible conflict of interest.

Despite having read plenty that advances the notion that publication is primarily of benefit to the author, about libraries and usage among other things, I remain baffled by this perspective. Yes, I see Joe’s point about demand because that speaks to sustainability for presses. But the error is in the equation. Comparatively low demand (comparative that is to the high numbers associated with some other genres of publication) does not mean no value to scholars or scholarship.

The projects I’m working on now have dedicated piles of books all over the place. My spouse just finished a mss. and step one after sending it off was to return boxes and boxes of books to the library. We are reliant on other scholars in order to contribute to scholarship. Scholarship generates knowledge through a form of conversation (a lot but not all of it happening via texts)–and by the point of publication a work of scholarship has usually been improved by engaging in a lot of conversation along the way (in conferences, seminars, or with fellow graduate students and committees *at a minimum.)

And to a related point (perhaps the books littering my house/office/car are the high demand/value ones), I was the book review editor for the major journal in my field (early American/ early modern Atlantic world history) for over ten years. I saw just about everything published in that field, and there certainly wasn’t much that I would say was of no value to other scholars. Some of greater value, some generating more scholarly debate, some having a longer shelf life. But very little was of value exclusively to the producer rather than any consumers.

Karin:

I think the issue is not so much the value of the book but rather what one is willing to pay for it. Publishing is as the say ain’t cheap! Just look at the list on this site of things done to a book before it is published.

I have consistently said that there is no free lunch. The market speaks and it often speaks harshly. Look at the prices that commercial publishers charge for a monograph and then what the University Presses charge. I do not see commercial houses saying they have to publish open access books. Indeed, Palgrave charges $100 for a 288 page POD history monograph. Thus, they have addressed the small market with a high price and by maintaining no inventory.

You say that you are returning books to the library. Was your husband prepared to spend say $90 or more for a book to do his research? That is a question I have not seen addressed.

In fact, Harvey, Palgrave does publish open-access monographs. And so have other commercial publishers like Bloomsbury Academic for some time.

Sandy thank you for the information. I stand corrected. Just looked at the Palgrave site and they charge $17,000 per title. It is available as PDF or on their e platform. Springer basically is data basing all their material and selling it as a data base to libraries. The one thing about data base publishing is that you have to constantly feed the data base. Thus, the merger makes more and more sense as time progresses!

On the Palgrave site is a comparison of various prices charged by the OA monograph publishers. Also, presented is the fact that none print that which is published. By ridding costs associated with PPB, inventory, distribution, etc it probably costs about $10-12K to produce a book. Not a bad business model. Almost as good as but not quite as OA journals.

But many publishers that do OA monographs also offer the option of buying POD editions, as we did for our OA Romance Studies series at Penn State. This is all handled by LightningSource’s POD operation, so requires no extra staffing or cost from the press itself. This is important because many scholars find that their P&T committees still want a hard copy (and so the author’s grandparents!).

Sandy: In looking over the Palgrave site many do offer POD publications for a fee to the consumer. However, they did not give a price.

The question, Karin, is what is the proper equation for measuring scholarly value? On the gold side it appears to be peer review plus someone’s willingness (and ability) to pay the APC. Would you accept that equation as a starting point? I doubt that effort expended, per se, is a measure of scholarly value. Life is not that simple.

Aren’t there any comments about desire for royalties? I never met a book author whose

ears didn’t pick up when it came to royalties. I do understand that for some

authors, just getting a book published is “their things.” Most authors I have met, of even the slimmest of monographs with barely a library market, still had “Harry Potter” delusions. Very few in the scholarly world wanted to just “give it away,” although altruist motives were often voiced.

There is an interesting video called “Success in the New Economy”,

It looks at the larger picture for education in society, particularly the US. It points out that there has been a basic ratio, 1:2:7 where for every one person who gets a masters or higher, there is a demand for 2 who obtain a 4 year degree and 7 who obtain a 1 year degree, certificate or advanced training beyond secondary. For the purpose, here, and by looking at the job market for Ph.D.’s, particularly in academia, there maybe an over production of Ph.D.’s, many of whom have expectations of finding a tenure track position where the “monograph” supposedly provides the ticket to that job space. As in the world of work outside of academia, there is an increasing number of individuals working in positions below the degreed qualification. And, in Academia, the number of Ph.D.’s working in non-tenure track positions appears to be increasing.

Thus, the need to publish a monograph by an aspiring academic may be pushing to create an oeuvre for which that high cost may not be warranted as in the purchase of a lottery ticket. STEM or STM degreed individuals have many more options to work at the level for which they were educated and hence their publications, of all stripes, has a larger audience or market, often well outside of the pub/perish academic domain and hence a much different value proposition for libraries and publishers, regardless of the perceived merit outside of the existence of the monograph as an entry fee for academic ladder. Q. E. D.

With more and more libraries moving away from a just-in-case purchasing model to a just-in-time purchasing model, open access monographs with effective preservation could support the availability of such scholarship down the road when a book’s time has come. I’ve organized panels on campus of faculty across the monograph oriented disciplines along with representatives of the university press who unanimously agree that every year quality scholarship is rejected for publication because there isn’t sufficient market for the proposed monograph. This can’t be a good thing for scholarship.

There has to be a better way to support these kinds of publications. And, as been pointed out above, there are numerous stakeholders and beneficiaries involved. Thus it makes sense to spread the cost across a broad spectrum and not just rely on an author’s institution or the immediate audience.

I think Open Access book publishing is going to be the future for university presses. As an academic librarian, the author’s points are good ones.

Here is the problem from librarians’ perspective: While the universe of available books becomes larger each year, our book circulation has continued to drop. While it is showing signs of plateauing, our book circulation has dropped 60% over the past five years alone. What this means is that the library does not have a justification for continuing to buy the same amount of university press titles as we did fifteen years ago. As we buy fewer books, some of us are moving to shared print collections/repositories, at the same time as we embrace Demand Driven Acquisitions.

However, this is still not an ideal situation. Ordering books through interlibrary loan is inconvenient and in some cases may shorten one’s borrowing rights. Additionally, many faculty in the HSS subjects complain that they don’t like reading books online. So what is the solution to this?

I think the solution is simply to fund OA monograph publishing for faculty. This will both make ebooks easily available and make them immediately accessible. It would also free up publishers to embrace print-on-demand services like the Espresso Book Machine, which could then become more widely adopted at academic libraries, for those who want to read a book of limited general interest but dislike reading on a screen. Publishers would have nothing to lose by allowing unlimited access and printing to books, as they would still be making money, but through the front door instead of the back door, as it were. I realize there are a host of entrenched logistical difficulties that stand in the way of such a revolutionary change happening overnight, but this scenario still looks more plausible to me than Gold OA for journals does, as the latter issue embroils one in many thorny problems that seem to be intrinsic to that publishing model.

Interesting comment. OA books are the solution to the problem. Question: is a faculty member in HSS willing to pay between $20 and $60 for a book produced by the Espresso Machine? The faculty member is used to walking into the library and checking out the book for free!

Additionally, where is the money going to come from to fund the HSS manuscripts? According to the studies cited in the paper it costs about $25K plus to publish a book. Say one does not print the book. Paper, Printing and Binding is not that much of the cost of a book. A 300 page B&W perfect bound book is about $1,800 for 300 copies. Thus, $1M gets you about 40 books. I am not too sure the provost would find those numbers appealing. On the other hand, how many books could the library purchase for $1M?

I find the problem with the OA model is that there is no income to off set the costs involved in publishing books.

Perhaps tenure committees and Universities have to re-evaluate the criteria for tenure for HSS faculty and remove books. Have books become an anachronism and the need for a multitude of university presses too?

Harvey, you’re not listening. Presses like Amherst cover their costs through endowment funds; no authors are required to pay anything. Other presses are fully funded to do OA publishing by their parent universities, as at Athabasca Press in Canada. Luminous at California is funded through library support in part. There are a variety of models, not all of which require authors to pay fees.

I am not sure you are listening. A $1M grant gets you 40 books.

I believe Amherst is an exception. It has an endowment of over $2.1 billion and its pockets are deep. Also, it makes some rather bold assumptions!

“In other words, when enough institutions make the leap into free publishing, the savings achieved—by no longer having to purchase (now free) publications from University Press X, Commercial Press Y and Trade Press Z—will more than offset the costs incurred when libraries contribute resources to support open-access publishing. When some critical mass of university presses make publications available to anybody with an Internet connection, the savings realized by libraries will more than offset the expense of running a press.”

https://acpress.amherst.edu/were-often-asked/

I am not too sure that many schools have that much money and the commitment to providing free books for everyone. Also, I don’t believe many commercial houses will commit to free publishing unless the author comes with a grant in hand. A grant that would cover costs and profits from sales!

Athabasca is not free to the author and they sell their wares:

The decision to publish is based on a variety of factors. Foremost among them is the text’s scholarly merit, but we also consider the size and demographics of the book’s intended audience, its overall marketability, and whether funding is available to assist with production costs. These costs are not trivial, and they increase in proportion to a book’s length, as well as with the addition of colour images.

For this reason, you will be asked whether you have access to funding to support publication, whether from your university or from an external grant. It is primarily the author’s responsibility to identify and apply to possible sources of funding, although the press will be happy to assist in this process as needed. One exception is the award provided by the Awards to Scholarly Publications Program (ASPP) and administered by the Federation for the Humanities and Social Sciences of Canada. If we determine that your manuscript is eligible for this grant, we will apply for funding on your behalf.

AU Press books will be sold to libraries through electronic aggregators, who do pay royalties.

http://www.aupress.ca/index.php/publish/

In my ideal scenario, faculty would not need to pay for books to be printed. The library could take on any costs associated with Print on Demand. The question of where the money is to come from to pay for HSS manuscripts is a good one, which I don’t have a complete answer to, but if $1 million produces about 40 books, then that seems like something that could be do-able.

From my librarian’s perspective, we are all in this together as part of the ecosystem. Libraries have space constraints and declining circulation, but we don’t want university presses to suffer as a result of us buying fewer books from them. The current situation doesn’t seem sustainable. Demand Driven Acquisitions is perhaps not sustainable either for libraries or publishers. What would be the best way for university presses to set themselves up with a model that ensures payment, no matter whether books are read by a hundred people, or by one person?

Books are not an anachronism, and we need to support them just as much as ever. But library and university administrators are NOT supporting them, yet faculty still need to publish them, and researchers still need to access them.

Some questions for a librarian

1. Why do you care about University Presses?

2. Do you have the same concerns for commercial presses?

I did not say books are an anachronism but possibly university presses are as is the requirement for a book to get tenure.

We came up with a plan for presses and libraries in the CIC (Big Ten plus Chicago) to do OA monograph publishing jointly way back in 1996. The history of this project and its later mplemntation in the Office of Digital Scholarly Publishing at Penn State Press (where I was director) is provided in my lead article in the April issue of the Journal of Scholarly Publishing. The Green OA verson of this article is accessible here: https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/files/x346dv41v

$1 million will not give you 40 books unless you already have infrastructure in place to support the OA initiative. Only looking at incremental costs is financially illiterate. OA monographs are MUCH more expensive than this thread claims. Palgrave et al get buy with their bargain basement prices because they do bargain basement publishing on top of preexisting infrastructure.