The Journal of Electronic Publishing (JEP) has a very good issue out now on publishing economics, which I recommend to everyone. (The issue is labelled “Volume 19, No. 1: Economics of Publishing,” a useful atavism.) There are a number of good articles here, including the very well-written introduction by the editor, Maria Bonn. I looked at a couple of the articles with special interest because, well, I had an interest: the piece by Paul Courant and Terri Geitgey on free riders in monograph publishing draws in part on data developed by Karen Barch and myself on behalf of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation (Karen and I expect to publish a report on that data on the Scholarly Kitchen by the end of the year), and I was an early reader of Nancy Maron’s piece. Taken as a collection, though, all the pieces here make an assumption about what publishing is, one that is not aligned with what publishers actually do.

The best expression of this assumption appears in the excellent piece by the aptly named Scott Smart and his colleagues. Here is the passage that set me a-pondering:

The charge of our investigation was not to develop a “profit-and-loss” statement for the press; in other words, revenue and other revenue-related considerations (such as royalties, which are a function of revenue) were identified, considered, and ultimately removed from the final analysis, keeping in mind that our goal was simply to determine, on a per-monograph basis, the “true” cost of publication.

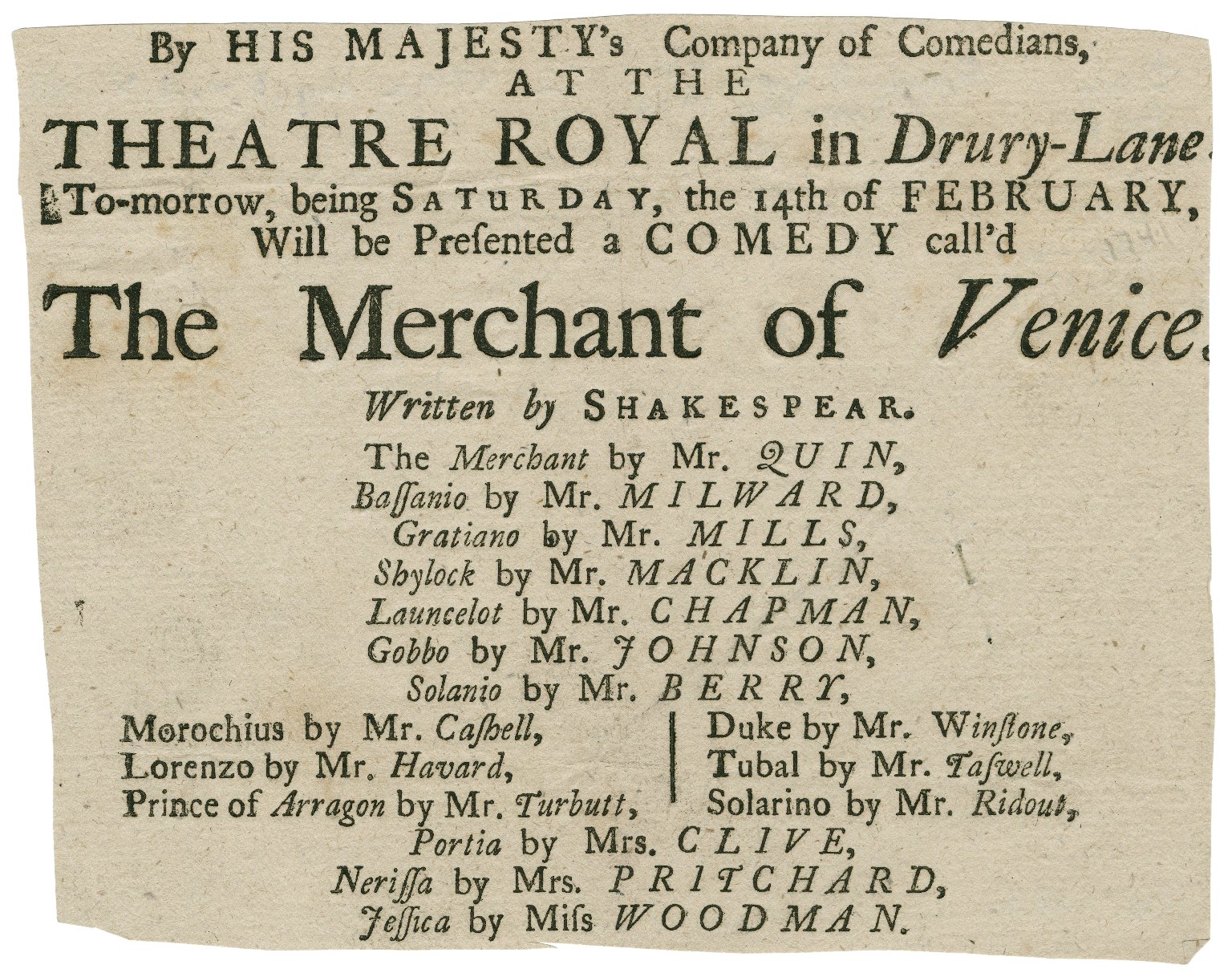

The scare quotes around the word true serve to make the point that accounting is not an unambiguous science but is ultimately open to interpretation. In Smart’s formulation, the cost of bringing authors to the list don’t count as publishing. Smart reaches this conclusion for a very good reason, namely, that royalties are a variable cost (the more copies of the book you sell, the more royalties you have to pay): If you want to get to the theoretical “first-copy cost,” you don’t include all the costs, or the revenues, that come after the first copy is created. As I said, Smart’s analysis is very well done. The problem is that Smart (and Nancy Maron in her paper) are not catching publishing costs; they are capturing production costs. This is not just semantics; production and publishing are different things (production is a component of publishing in the same sense that a pound of flesh, say, is a component of a human being). I hasten to add that knowing the cost of production is a very important thing and between Smart and Maron the community is well served with the analyses on offer. But if you want to know what it costs to publish something, you have to look elsewhere.

Whenever someone talks about the cost of publishing, the conversation seems to me to take place in a vacuum. Step inside a publishing company and ask this question: Where is the greatest amount of energy expended? The answer is in finding the best authors. Publishing, in other words, is about the relentless pursuit of the best content for a particular program, and the best content comes from the small number of people who can create it. Publishing is brutally competitive, but the competition takes place not so much downstream in sales and marketing but upstream, where editors step into the ring every day, determined to knock out their rivals.

There are a number of ways editors attract the best authors. Most obviously (and particularly true for trade publishers) is the payment of an advance and royalties. Even scholarly publishers, including small university presses, will at times pay advances (some advances are fairly large), and just about all book publishers pay royalties when a book has sold a certain number of copies. But there are other ways to entice authors as well. University presses, for example, may trade on their reputation — the reputation of the parent university, the reputation of the press itself, or perhaps the reputation of a particular program at the press. Thus there is a university press that is regarded as the place to publish on the history of the American South, another for international studies, and two or three that battle for the mantle of best list in anthropology. As I write this paragraph I imagine that the staff of some presses may be reading with special attention: Is he talking about us? I won’t let the cat out of the bag, but I will say that if I were publishing in architecture, I know where I would send my manuscript; and the same goes for American history (several candidates here, but one sits above the others) and economics. Yes, press-people, I am indeed talking about you.

Presses also attract authors through their marketing presence (“We attend MLA every year”) and their networks of authors, advisors, and editors. Persistence helps, too: many a book has been acquired because of the tenacity of an editor pursuing an author over a long period of time. Sometimes the only way to get rid of the editor is to submit the manuscript. It is a source of amusement to me to observe how the highly-educated, bookish, ultra-polite editors at university presses sometimes talk about their rivals. There is as much focused energy here as there is on a football field or on Wall Street.

None of this is captured by Smart; his analysis gets at everything except what makes publishing publishing; and I want to repeat that his assumptions are implicitly or explicitly shared by all the articles in this issue of JEP.

So now we know how much it costs to produce a scholarly monograph, but how much does it cost to publish one?

Publishing is best viewed as having two complementary parts: frontlist and backlist. The frontlist is the books that you are publishing this year; the backlist is the list of books that have been around for a year or more. Some publishers qualify this a bit (e.g., the frontlist is said to cover two years, and the backlist may be divided into recent backlist and “deep” backlist), but the principle is the same. Every book on the backlist was once a book on the frontlist and, with rare exceptions, every book on the frontlist has a future on the backlist. Thus a snapshot of a press’s program at any point in time shows us the life cycle of an average title. Smart’s analysis does not capture life cycle costs, though it does capture much of the frontlist cost. The backlist cost is entirely missing. This is important because the backlist almost always operates at a profit; and that’s true for the smallest presses as well as the largest. By not including the backlist in the analysis, the alleged cost of publishing to the parent institutions is vastly overstated.

But to get at the cost of the backlist (as well as some of the frontlist costs), you have to include the costs incurred to generate revenue. Those costs are largely in sales and marketing, but also include the cost of printing and binding and online hosting. And of course you have to include whatever you pay to authors and advisors. In fact, you have to include all the costs of the press.

This is a complex calculation. In order to accomplish this, you need some sophisticated tools: the back of an envelope, a pencil, and five minutes. With these tools in hand, you now look at the total costs incurred by a publisher. Let’s say that a press has costs of $11 million a year (and revenue of $10 million, for an operating loss of $1 million a year). This press publishes 200 books a year. You then divide $11 million by 200 and find that the cost of publishing at this press is $55,000 per title. That may seem like an enormous amount of money, but bear in mind that the press earned back $10 million of the total cost in the marketplace — and you are assessing life cycle costs. Another way to do this calculation is to take the operating loss of $1 million and divide it by 200 new books per year. This leaves us with $5,000, the cost to the press’s parent institution per title. Smart’s and Maron’s figures are much higher than this because they don’t include the offsets to the institution’s costs from money earned in the marketplace.

Let’s not stop there. Imagine a larger press, with costs and revenues both running at $20,000,000 a year. The number of new titles is 300, giving us a cost per title of $67,000. But the cost to the parent institution is zero because this press operates at breakeven. Or we might have a smaller press, with $5 million in costs and $4 million in revenue. This press publishes 150 new books per year. This press has a cost of $33,000 per title. The cost to the parent institution is $6,700 per title per year.

You can do calculations like this all day long and what you will find is that the numbers are all over the place. And they should be: the cost of publishing varies with many things, including the overall costs and revenue of the press and the number of books published each year. The costs to the parent institutions vary as well: the better the sales and marketing of a press, and the larger the backlist, the lower the cost of publishing to the parent. And in many cases the cost to the parent is actually a negative number because the press is profitable.

What Smart is doing is what I call the “Shylock analysis.” He is looking for a pound of flesh, but the real cost includes the blood. The cost of producing the first copy of a book cannot be analyzed outside the context of the press’s overall operations. At least it can’t if you are talking about what it takes to publish something.

Production, on the other hand, is a different matter. It can be done for much less than Smart says: all you have to do is give up the cost of attracting the best authors. That would allow you to scale down your editorial effort, as you don’t need to invest much in editorial if all you are doing is operating the digital equivalent of the campus print shop. We see this in the world of Gold Open Access, where PLOS ONE changed everybody’s understanding of costs by reducing the scope of editorial review.

In my view, we don’t have to decide which method is better: viewing publishing as simply a production process or viewing it as a matter of careful selection, whose success is measured by marketplace demand. Over time these two processes will either eliminate the other or each find its own place. But let’s not confuse one with the other. That would be neither true nor smart.

Discussion

20 Thoughts on "How Much Does Publishing Cost?"

The cost and challenge of finding the best authors is discussed for books, which are large projects. What about journals, where each article is a relatively small project. Do journals actually look for authors?

Yes, commissioning for content for journals is pretty common, particularly for review-type articles.

It depends quite a bit on the journal. For high quality journals, a great deal of time and effort is spent on recruiting the best authors and papers, planning special issues and sections and bringing in the best authors and guest editors for those issues/sections, etc. Editors will often attend meetings in order to recruit authors from the best talks and posters as one example of costs.

If you’re in the quantity business, you’re less concerned with the quality of the work or any specific author, and instead what you care about is recruiting lots of authors. This has costs as well.

Yes, but none of these are costs borne by the publisher. They are costs borne by the universities who pay faculty that do these tasks.

Sorry, no.

If the publisher pays the editor’s way to a meeting, provides them with journal business cards and materials, that’s not paid for by a university. If the journal does a “call for papers” and heavily promotes it and buys mailing lists to send notices to, the university does not pay for those costs. If the journal makes special efforts to promote the work of authors and offers them other features and useful reporting mechanisms, the university does not pay for those things.

Really, I have no idea what sorts of costs you’re talking about. Also, note that many journals employ editors that are not necessarily university employees.

Re those high quality journals, I developed a procedure for DOE’s Office of Science that might be useful. It was for finding new reviewers for proposals and it consistently found researchers the Program Officers were unaware of, so it should work for new authors. Even in a narrow field, nobody knows everybody.

The basic procedure is simple enough. Start with a small set of papers that are central to the topic. Use Google Scholar’s “Related articles” (RA) function for each paper. This is the big trick because GS RA uses semantic analysis of entire papers, not keywords. GS returns a list of about 100 hits for each starter set paper. Look for papers that occur in most of the RA hit lists. These will be very close to the central topic. Then look for new authors in these frequently occurring papers.

You can also do this over time to see new authors entering the topic and old ones leaving. It turns out that researchers can be pretty nomadic when it comes to narrow topics, often moving from one to another, like oases in the desert. One can also see how the research radiates away from the central topic in different directions. This is basically a science mapping tool.

David: Thank you for sharing this procedure. It’s a very interesting approach, but I would imagine very labour-intensive, and used only for proposals in the later stages of review? Or were you able to automate this somehow?

Paul: The prototype automated pretty simply. (The SBIR program we worked under was terminated, not because of us, so that is as far as we got.) We automated finding the core set by using every article for the last n years with a specified term in its title. If the term is in the title you know that is what the article is centered on. Picking that term is something of an art of course.

The output ranked all the related articles by how many times they appeared in the related article sets. So all one has to do is specify the search term. I call it the Inner Circles Method because the ranking is like concentric circles of closeness to the core set articles.

Proposals are big ticket items so a certain amount of work is justified. For journals one might want to add people to the reviewer database or some such. But a simple manual version works pretty well too.

Interesting analysis by Joe and I would add that their is the cost of failure, i.e. a book or a journal fails and that too is a cost. It seems to me that everyone is a publisher until they actually have to publish and sell what they issue.

David: Journals are always seeking the best authors as well as the best articles that is why they review and have editors-in-chief. However, I think in OA it is different in that it is not what or who you publish, it is only that you publish something.

“Publishing, in other words, is about the relentless pursuit of the best content for a particular program, and the best content comes from the small number of people who can create it.” This is why “internet publishing” is an oxymoron. And no, Mr. Esposito, those aren’t “scare quotes”; they indicate irony.

It is very difficult to calculate publishing costs that can be used as a comparison across presses, and the main reason is that the subsidies universities provide to their presses vary quite widely. Some presses may not have to pay the benefits costs of their employees because they are part of the university’s overall benefits plan. Some presses get free office and warehouse space. Some get free legal service. Etc. The analysis Joe does therefore only gets us just so far.

The best method for taking all publishing costs into account is the one that Herbert Bailey, former director of Princeton University Press, wrote about in his book “The Art and Science of Book Publishing,” which remains in print today. It provides a very refined method for breaking down costs into various categories, which are then used to estimate what the full costs of publishing a book are. I urge people to take a look at this book, which remains in print today and was recently called by the Yale Publishing Course the one book to read if you read only one about scholarly publishing.

Perhaps one might do this analysis for monograph and journal publishers who do not have permeable boundaries for cash flow from a parent such as a university or foundation, the private sector such as Elsevier, Springer or ….. Then ask the simple question as to whether they are profitable in that they have a net positive or negative pretax revenue. If it is negative then they will cease to exist unless they can figure out how to return to profitability considering all the variables so eloquently analyzed here.

The issue for academics and others who want the information is the cost to the buyer or users. All the analysis here, while important, seems like an academic exercise, in part to respond to the concerns of the end users who see that the major private sector publishers do not seem about to go out of business. The university or related publishers have other issues which may or may not need to be addressed.

You make a very good point that recruiting papers is competitive, and journals ignore this at their peril. As editor-in-chief of a respectable science journal, I spent about 40 percent of my budget (time and travel) attending the organization’s three conferences (annual, two specialty) each year and scouting out potential papers. Not to give away trade secrets, but it was extremely beneficial for our journal’s quality as well as Impact Factor.

There are a lot of questions here I think before a figure could hope to be reached. It’s flawed to divide the number of works published by the running cost – what of business efficiency?- but equally flawed to consider production costs as publishing costs. Having worked across editorial and production roles, and now working for a publishing solutions company, I think there are more angles to this than the Hope Diamond. Facilitating scholarly communication by identifying and securing the best authors, ensuring timely and accurate publication, and delivering that content on a platform that supports the research experience is a team effort. To identify the cost of publishing (rather than publication) would require these strands to be isolated and collated across a wide enough dataset. I for one, would love to read those results.