Editor’s Note: This piece is co-authored by Lisa Janicke Hinchliffe and Oya Y. Rieger, Senior Advisor to Ithaka S+R’s Libraries, Scholarly Communication, and Museums program.

Last week, Roger Schonfeld discussed how several libraries are increasingly scrutinizing the value of their license agreements with greater attention to alignment with their own strategic interests in light of recent negotiations and cancellations. The financial pressures inherent in Big Deal agreements are often combined with an interest in using them to fund open access publishing. So while some libraries have cancelled their Big Deal contracts outright and changed to title-level subscriptions, others have sought to have them re-born as “transformative agreements” with publishers, with libraries funding both reading and publishing.

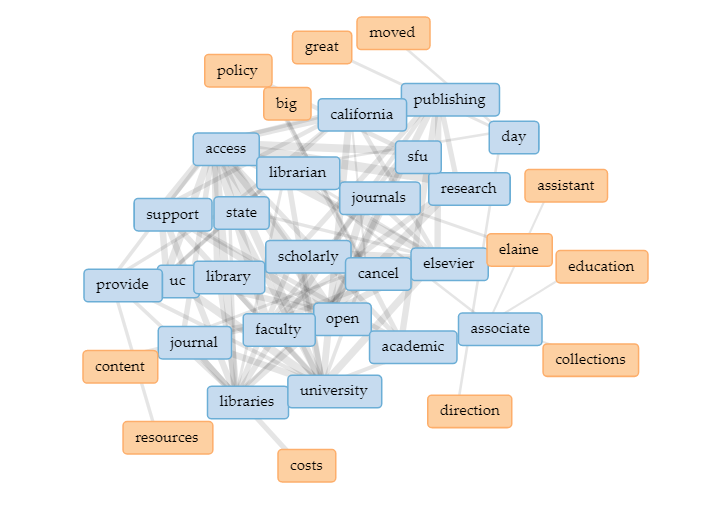

The number of statements that California’s action of canceling their Elsevier Big Deal has garnered exemplifies how attention is currently focused on library-publisher negotiations. Today we look at those statements with an eye to understanding what they might reveal about open access publishing, institutional priorities, and the role that library-publisher contracts might play in this arena.

In examining these statements in detail, we quickly realized that there are some common themes as well as interesting divergences in areas of emphasis and positioning. We went through almost three dozen statements (see University of California Scholarly Communication for a collated list) to analyze the similarities and differences among them, and actions promised by them. We offer our observations with a goal of furthering the dialogue on the important issues currently facing both libraries and publishers about open access publishing in scholarly communications.

The statements take a variety of positions, spanning from criticism of commercial publishing (especially large publishers with steep pricing and large profit margins) to advocating open access more ideologically. Here are the key characteristics we noted in our review:

- Authorship: The statements are predominantly written by library leaders. There are, however, a few from senior university leaders such as Provosts or Vice Provosts of Research.

- Claim — System is Broken: The primary argument put forth is that the current knowledge sharing system is no longer fit for purpose and that there is a need to shift to a sustainable and open publishing ecosystem.

- Claim — Needed Interventions: The statements vary in the kinds of interventions that they call for. Some highlight exploring alternative models for supporting open access dissemination of content. Others make a case for transparent and affordable pricing of formal open access publishing, typically coupled with a desire to control open access article processing charges (APCs).While some suggest that the system is reaching a tipping point, regardless of which intervention(s) a statement highlights, the overall suggestion is to shift funds to support open access rather than continue expenditure on closed for-profit publishing.

- Justification — Access and Impact: Some statements view scholarly communication through a lens of diversity and inclusivity and argue that scholarly publications should be accessible across all educational systems and to the public at large. Additionally, these statements mention the analysis that has shown greater use and citations of open access publications in comparison to those that are not open.

In addition to rhetorical positioning, some statements imply a promise of action:

- Future Negotiations: Some refer to either ongoing or upcoming negotiations with prominent publishers; however, they stop short of making any projections about desired outcomes or “lines in the sand” that would cause cancellation.

- Raising Campus Awareness: Some say that the California cancellation has been an opportunity to start campus conversations about the Big Deal and its implications. These conversations seek to raise awareness of the challenges library budgets face and also to explain the specifics of the UC’s cancellation of Elsevier contract. There are several general statements about the intentions to work with the campus academic communities to continue to advance our advocacy and support for open access.

- Promotion of Services: Some are leveraging their support statements to promote their institutional repositories, open access policies and mandates, APC support funds, and related service consultancies for copyright, publisher agreements, and public policy compliance.

Reviewing the support statements have raised several questions for us:

- What happens after cancellation? How do libraries and scholars adapt? A 2017 literature review by Sjoberg revealed that, although there is some research on cancellation decision-making process, what happens after does not get sufficient coverage in the literature. There is a scarcity of testimonies about the positive or negative outcomes of cancellations, assessment strategies deployed, and engagement of faculty and students in post-cancellation reviews. How are we going to know if and how the cancellations have impact on research? A notable exception is the recently presented systematic post-cancellation assessment in Sweden. Research on the search and use of scholarly articles more generally indicates that researchers use the most convenient and readily available means to discover and obtain information rather than pursuing comprehensive strategies. Are researchers going to try to acquire the articles to which their institutions don’t subscribe through interlibrary loan, etc. or will they settle with what’s conveniently available?

- Is there a turn from crisis to strategy? Most library leaders already know where they want to invest and which programs they would foster if they were to have additional funds (see Figures 11 and 14 in Ithaka S+R US Library Survey 2016 Survey) and collections, publishing, and related staffing are relatively low in priority. California’s action, which parallels the still in force cancellations in Europe by Germany and Sweden, has emboldened some to consider cancellation as a potential negotiation tactic — both in pursuit of open access but also for cost containment. What would it look like for libraries to develop a more intentional and long-term strategy to reclaim control of collection budgets without reacting at points of financial crisis?

- Transformative agreements — maybe/maybe not? The statements are notably quiet when it comes to committing to pursuing transformative agreements that would fund open access publication. It seems there is an ongoing debate about the promise of green vs. gold open access and questions about the desirability of propping up the value of the offerings of commercial publishers. It is well documented that transformative agreements lead to research-intensive institutions and countries paying more as costs switch from paying to read to paying to publish. Are transformative agreements sustainable, if there are no price caps, if they succeed in shifting the industry to paying for publication?

We are not the only ones who are thinking about how the subscription environment is shifting and its implications. We were delighted to note that L. Angie Ohler (University of Maryland) and Joelle Pitts (Kansas State University) are investigating the issue directly. They are currently surveying academic librarians in order to address this question: “In the aftermath of the recently publicized breakups between academic libraries and academic journal publishers over renewal of “big deal” journal contracts, are academic libraries consciously planning for, or already making the pivot, to supporting open access initiatives as an alternative to traditional scholarly publishing practices?” We look forward to seeing the results!

In the meantime, we invite comments on this piece. What themes are you noticing? What questions are being raised from your perspective?

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "What Do Statements of Support for California Tell Us About the Big Deal?"

Would be great to see a bibliography of the “almost three dozen” statements you looked at. Thanks!

Lisa references this list from UC’s Office of Scholarly Communications website: https://osc.universityofcalifornia.edu/open-access-at-uc/publisher-negotiations/uc-and-elsevier-impact/

Apologies, don’t know how I missed that link….

I continue to see a wonderful opportunity for the U Cal system to lead efforts to significantly contract the number of subscribed journals. Regardless what one thinks of the specific way Bradford’s Law has been articulated, surely the insight that underlies it is correct: a subset of journals contributes significantly to dissemination of knowledge. In my view, OA advocacy is consistent with a concern about the astronomically increasing number of articles in all fields, but one does not hear much (or at all) about just how problematic this fact is for inter-generational transmission of knowledge. The latter is a core goal of librarianship.

Along these lines, I’ve been wondering whether the U Cal system has contended with the research findings, reported in TSK some months ago, that argue that APCs are more inelastic than at least one statement from U Cal suggests and that was used to justify library funding (or in this case, funding by a state system) of APC charges.

I also continue to wonder why there is not a lot more scrutiny of the complementary role that preprints can play with respect to peer-reviewed publications. (I’ll hopefully have up a third version of my preprint about this topic, in relation to arXiv, and then work on a version for possible journal publication.)

There are big challenges to effect reforms along the lines suggested above, of course.

P.S.

It will be quite interesting to see what ILL activity U Cal experiences in the wake of its decision not to renew one of its big deals. What will that ILL activity say, after close analysis and surveys of faculty, about the real (as opposed to perceived) need by researchers for so many journal subscriptions? (Comments reflect my own views.)

To ILL you have to add the data from Sci-Hub, ResearchGate, and many others, if you can get it.

That’s definitely the case, to get a full picture. In lieu of a very complicated statistical analysis based on all kinds of assumptions, surveys of the user population would be the best hope. They’d have all the usual limitations of surveys, but on the other could be very useful in getting the barometer on user perceptions about the need for so many journals and whether journal articles behave as economic substitutes. This data about perceptions would be useful to university administrators understandably concerned about losing political capital by significantly cutting down on the stock of journals they make available.

Let’s be careful to un-pack “make available”. I would argue that subscriptions/ownership/licensing are one set of strategies we use to make stuff available to our users. Supporting open makes stuff available, encouraging sharing makes stuff available, green OA makes stuff available…. I’d like to shift that entire narrative to be about what we make super-conveniently available. When we cancel a subscription to a widely distributed and highly-available resource like a journal, we aren’t saying our users are forbidden from getting it, nor that we won’t help. Let’s talk about what things we need just-in-case (i.e., highly-likely to be used a lot) vs. the things we can get on-demand. The price of everything-right-now through institutional licensing just doesn’t always add up to a good value for many titles…

Brian, you are missing the obvious point. If you want to reduce the number of journals, only purchase at the library journals with a high JIF. Let authors fight to get into the top journals. Problem solved. As for the other problems this strategy would create, heh.

Joseph, do you have a suggestion for better metrics than JIF? We’re finding more and more that those are propped up in many journals by a small numbers of very “hot” articles….

Several points. First, my comment was a rhetorical response to Brian, who does not seem aware of the implications of what he is asking for. Second, I am a “metrics moderate”: I think the obsession with metrics is preposterous and are no substitute for human judgment. Third, it depends what you are trying to measure. Altmetrics measures marketing, for example. JIF measures citations (imperfectly). Fourth, citations have significance of a special kind for research, for which there is no known substitute. Finally, although people try to game the system, the system is still mostly reliable. JIF is a “B.” There are no “A’s”.

Joe, I’d never advocate crudely taking JIF’s as a metric to effect contraction in the journals market. Why would anyone advocate that? Why would I advocate that? JIF’s would be highly problematic for this project and in general are well known to have many problems.

I actually share your unease with metrics. But I’m not convinced that they are entirely worthless, by any means. We need a plurality of metrics to evaluate the quality of a journal, including subjective appraisals by researchers. On a different front, when it comes to crucial tenure and promotion decisions, much more needs to be placed on holistic evaluations by peer evaluators who write letters of evaluation for t an p. But even the latter is problematic. A professor once remarked that he never saw a letter of evaluation that was not positive. There are drawbacks and trade-offs in all approaches.

This would be too much too quickly, in my view. I could see a U Cal taking an incremental approach that would involve surveying faculty as mentioned to assess interest in a gradual contraction in the stock of journals. The idea is to get a discussion going through advertising survey results.

Tenure and promotion practices of course reward large quantities of publication in addition to publication in high quality journals, however defined. I could see tenured faculty taking some interest in this approach, though. No asst prof in their right mind would take on these issues. They worry about survival.