Headlines remind us that the crisis of higher education in the United States, in which universities that are squeezed for resources are cutting programs and staff, has accelerated with the COVID-19 pandemic. A review by the Chronicle of Higher Education estimated that the pandemic will have cost higher education $183 billion. Hundreds of thousands will have lost jobs in the sector. The impact on humanities programs and positions are likely to have been hardest hit. This is not unique to the US.

At the same time, another crisis has been long unfolding, mostly out of the headlines except when protests erupt. Mostly, though not exclusively, private universities in cities have expanded their real estate holdings, become substantial and sometimes dominant local (even regional) employers, and turned their security into police departments, all with serious consequences for urban communities — primarily communities of color. A longstanding ideal of higher education has underwritten both tax exemptions for universities and new public-private partnerships that further marginalize existing communities.

At the same time, another crisis has been long unfolding, mostly out of the headlines except when protests erupt. Mostly, though not exclusively, private universities in cities have expanded their real estate holdings, become substantial and sometimes dominant local (even regional) employers, and turned their security into police departments, all with serious consequences for urban communities — primarily communities of color. A longstanding ideal of higher education has underwritten both tax exemptions for universities and new public-private partnerships that further marginalize existing communities.

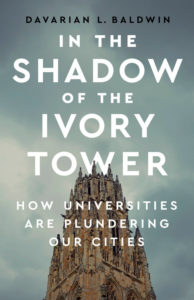

There may be a better path forward, and, post-pandemic, this may be exactly the time to commit to it. But we still need to have a clearer sense of just what’s happened. Davarian Baldwin’s new book, In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities are Plundering our Cities, takes a close look at universities in cities including Baltimore, Buffalo, Chicago, New Haven, New York, Phoenix, and Pittsburgh — and Winnipeg. Dr. Baldwin is the Paul E. Raether Distinguished Professor of American Studies and founding director of the Smart Cities Lab at Trinity College, author of Chicago’s New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and BlackUrban Life and co-editor, with Minkah Makalani, of Escape From New York! The New Negro Renaissance Beyond Harlem. With research that included 100 interviews with administrators, faculty, students, and staff, as well as community activists, he shows the impact of university expansion and intrusions. A believer in higher education and its public mission, he also has ideas — and an example — of how things could be different.

I sat down with Dr. Baldwin across Zoom, to ask more about how he’s come to understand the role — and the potential — for universities in American cities. Below is an edited version of our long and very rich conversation. Dr. Baldwin addressed a host of related issues in our conversation, including the history of racist urban development, the explosion of student loans, the experiences of low wage workers including graduate students, and the history and recent steps at his own university, Trinity College in Hartford, that I’d encourage you to read about in the book.

Could you start by telling us about the famous Checkerboard Lounge blues club on the Southside of Chicago, and the University of Chicago? This is a story that you introduce the book with, and it seems to contain many of the themes that you follow in other cities, with other universities, and you watched some of what happened unfold.

I was in the library doing archival work and I stepped outside and it was unfolding right in front of my eyes. I heard these chants and sounds and came to find out that protesters were demonstrating because the University of Chicago had decided to relocate the Checkerboard Lounge from the historic black neighborhood of Bronzeville to the commercial corridor of the University and its Hyde Park campus neighborhood. There were some in the crowd charging cultural theft.

The simple act of a university buying and relocating a blues club from a historic black neighborhood to a campus neighborhood was instructive to me.. It demonstrated the political and economic power of colleges and universities in ways that has nothing to do with what we consider higher ed’s traditional and primary function, teaching classes and conducting quote unquote pure research. The university had acquired this cultural asset to help anchor its control over real estate, employment, healthcare, and policing in the city. It highlighted a growing convergence between university administrators and city leaders and their broader desires to reorganize space, to turn neighborhoods around their campuses into an urban playground to draw, not just students and their families, but also investors in related industries, into this kind of island of prosperity with state of the art amenities, retail, housing, health care, all protected by one of the largest private security forces in the world, the University of Chicago police department, that could and would keep the largely Black and increasingly Latinx poverty that’s around it, the growing campus, at a safe, regulated distance. So in short, I was being introduced to a new model of urban and economic development where higher education stands at the center. And this is a story that was not just unique to Chicago.

This is also a story that could be looked at in rural areas in college towns. But as an urbanist, I was coming to this as someone who’s interested in what’s happening in cities.

Tell us how more about how you want us to think about universities as economic actors within cities in particular.

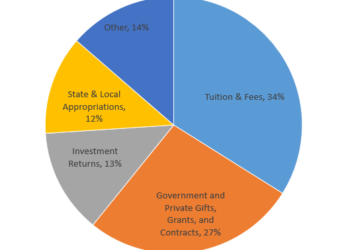

The critical way in which they’re able to amass so much wealth is because we don’t see them as economic entities. We don’t see them as businesses, we see them as institutions of learning. As I say throughout the entire book, the presumption of higher education as a public good does a lot of financial work. They engage in financial transactions under the cover of our presumption, that all they do is teach classes and conduct research. So we talk a little bit about their endowments at most, and many schools have multi-million and some have billion dollar endowments, most of it sitting in money market accounts, accruing interest, but these numbers are simply a portion of the wealth that flows through and is managed by these institutions of higher learning.

A major portion of higher education wealth comes from real estate acquisitions and public private partnerships. Another is in what I call today’s knowledge economy. The Bayh-Dole act of 1980 allows schools to prioritize their research as intellectual property, sell it on the private market, and then reap the royalties. So then federally-funded academic research is used to create profitable commercial goods and services in a range of fields from pharmaceutical industries, software products, to military defense weaponry. Schools rightfully brag that these projects, these partnerships can generate life-saving discoveries and they do. But these schools are also competing with each other to recruit the best and brightest. So if you’re a University of Chicago in the middle of South Side, if you’re at Columbia in the middle of Harlem, there’s a perception of danger, whatever fear. So key to recruiting is creating these urbane clusters of laboratories, housing, retail, and nightlife. We call these innovation districts or knowledge communities that not only sit right in the middle of existing communities of color and working class neighborhoods that are around campuses, but most of these properties remain tax-exempt because of higher education, nonprofit status.

So this becomes the whole shelter economy that also passes the burden of property taxes on to the cities and the neighborhoods around them that are filled with tax-starved public schools and public services that university affiliates benefit from, but don’t pay for. So you have all these tiers where universities are actually not just benefiting from being in cities, but they’re actually extracting wealth. And the wealth they brag about literally is directly extracted from the taxes that they don’t pay into the federal government, the taxes that they don’t pay into the cities, and the market rate costs that they charge for these discoveries that are then never given to the community.

You mostly focus on private universities, but is there a story here about public universities, too?

The difference is not so much between public and private, because some public universities are doing a lot of the same kind of work, UVA, the University of Michigan, the California system, and ASU, which I talk about in the book. Some of that is because in just 20 years, the state contribution to supporting public universities has collapsed. So the argument at these public schools is that they’ve got to be entrepreneurial, right? I understand that. But I think the real divide is not between public and private. I think the real divide is between the profit-oriented nature of the administration in universities — not all cases, but in most cases — and the public good orientation of faculty and staff. And so what you actually have is a bifurcation within universities, around competing missions. You have these amazing scholars and staff that were putting together ideas about community engagement and civic outreach, and in the same school, you have a real estate office or administration that is going to buy up land to build amenities like movie theaters and high-end retail for our targeted students, to the detriment of the existing residents. The school, the staff and the faculty members, and the administrators were all using the same language of anchor institution, of civic engagement, of community outreach. But what they meant was very different.

Why is the rise of university police forces so important to this story?

Campus security largely started out as general support staff, keeping students out of trouble. But then by the time we get to the 1960s and 1970s, largely in response to cities that surrounded campuses becoming browner and blacker and poorer, schools wanted to assure mainly white parents about safety, and as students and communities started engaging in social protest, police forces were ramped up to clamp down. Then we also have another wave of explosive campus policing in the 1990s and 2000s that didn’t even really have as much directly to do with campuses, with mass shootings. But we have to look at what have been the primary crimes on campuses. The major crimes on campuses are theft, drug use, and sexual assault. If you’re trying to sell the brand of a university to ambassadors and the families of students, you’re not going to want to publicize largely white on white crime amongst your students. What you’re going to want to publicize is that yes, we know we live in increasingly poor and brown neighborhoods, and we’re going to ramp up police to point outward to show you that your children will be safe. So the reality when it comes to campus policing is that there was a total disconnect between the actual functioning of police and the need for public safety. Campus police have been creating extra-territorial jurisdiction because as schools expand out into what is considered to them relatively cheap land, these innovation districts and these retail and housing corridors for their faculty and students that want an urbane experience, a Disneyland version of the city that’s fully safe and hermetically sealed and really is reflection of their old suburban life. So it’s full of Trader Joe’s and Shake Shacks and Lululemons. The police need to surround all of that to offer extra-territorial jurisdiction and authority as campuses expand across cities and these black and brown communities. So now we have, in certain cases, memorandums of understanding between campuses and cities where armed public and private campus police either have jurisdiction over any politics for campus buildings like U Chicago, or they have agreed to give campus police jurisdiction over entire cities in the case of Cincinnati or New Haven. So what this means is that you have, in many cases, either a private police force or a public police force that served the interests of a university first — so a private or quasi-private police force with public authority and no public oversight.

One of the people I interviewed in Chicago said that he used to walk on campus and get surveilled, but then after a while, he couldn’t even walk outside of his front door without being profiled because the campus police had jurisdiction in his own neighborhood. What does it mean that your entire life is now governed by the interests and the needs of the campuses?

How have communities fought back against university expansion?

There are wonderful historical examples that show communities protesting for alternative ways of imagining what the university can be. During the Cold War rise of the knowledge economy, universities became these battlegrounds over simply continuing to educate and train literally a white, white collar labor group, or what’s going to happen to the increasingly brown cities? Will they have access to this new, white collar world or will they simply be service workers in that world? We know what happened. They became ivory tower working class. But in that critical moment, they saw the handwriting on the wall and said, not only do we want to enter into this work world, but we also want the university to be something different. We want this university to be in service to us in real ways.

We can look at the City University system in 1970 and Black and Puerto Rican students and their white allies said okay, it’s great that the City University system has free tuition. But our public schools do not prepare our communities to meet admission standards at these colleges. So public universities, it’s your job to compensate for the inadequate education of public schools, so that we can prepare our citizens for social mobility.

In 1966, the neighborhoods of Oakland saw Merritt College as an extension of the north Oakland neighborhoods, speakers in the cafeteria, an incubator for re-imagining policing, re-imagining social relationships. In 1968, Columbia was trying to put a gymnasium in the middle of Morningside Park where there would be separate entrances for primarily white students and the primarily Black community — also with limited hours. When residents and students saw this, they charged Jim Crow — G Y M Crow — and they occupied university buildings for over a week. It was one of the biggest occupations at that point in the history of cities, not just universities. Aunties and uncles from the community were sending in soul food plates to sustain students in protest. So this is a moment where community members and students came together. Other protests at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Chicago, at Trinity in Hartford were important as well.

In recent years, the NYU faculty protested the Sexton plan, a land grab in Greenwich Village. The Community Benefits Agreement Coaltion in Chicago sought to claim resources as the University of Chicago-backed Obama Presidential Center brought in investors and then inflated land values in the neighborhoods that threatened displacement. You got to know it’s tough fighting against Obama! Obama is the son of Chicago. And so at first they couldn’t even figure out a way to get into the conversation. They put together the coalition of community groups and interested faculty at U Chicago. And they are trying to put together a policy to institute things like a property tax land trust, so that aunties and uncles who are on fixed incomes and grandmamas who are on fixed incomes, who can’t afford for the property taxes to go up, can pull from this land trust to compensate for the inflated value so they can stay.

Especially in the aftermath of pandemic, and of the racial reckoning that many universities as well as communities are engaging in, is there a better path forward? Perhaps like the one that you’ve described at the University of Winnipeg?

So I’m going to be honest, when the pandemic arrived I thought this book was going to be totally irrelevant. But then serious conversations developed about the future of universities, and after the social protest in the reckoning of summer 2020, people began to turn their attention to universities, policing and gentrification. The book became a project of academic research that was in service to a social reckoning. To be in the middle of this moment where we’re talking to community groups and student groups and faculty groups and city leaders about ways to think differently about universities specifically, not just because there are these ivory towers, but because they are the shop floor of city workers of whole cities. So to have this book be able to speak to that and get people make sense of that…it’s just been, I have few words. I’m humbled and honored for this book to be in service in that way.

And I’m a builder, I’m a dreamer, so I want to end with possibility. At the University of Winnipeg they have a vision of sustainability. Now it’s not perfect, but they take this vision of seriously. And it wasn’t just all benevolent. It was in their interests as a university that was growing and serving an increasingly non-traditional Indigenous and New Canadians (immigrant) student population. They built new housing with Indigenous community needs and values in place, as well as scaled rents. They fired their food supplier and created something called Diversity Foods where 65% of supplies come from small family farms within a hundred kilometer radius. Every workstation has a compost bin and cooking oil is shipped off and turned into biodiesel. On the employment side, at least 65% of the workers are from marginalized communities. They added affordable childcare slots. A faculty member fought to move an urban studies center into a hotel in the majority Indigenous north end of the city, and it’s now thriving.

You know, people want the university in their backyards. They want the schools to be there, they don’t want to have to leave because they can’t afford to stay there or because they can’t deal with the policing apparatus. They want all this. They just want to be there to enjoy it. Campuses could be the model for public safety instead of the model for incommensurate, ineffective policing. Schools that have these medical facilities could lead the way in police abolition towards units of care with trained trauma and healthcare workers actually meeting the needs of public safety. Schools could also address critical public safety needs of food and housing insecurity by diversifying their new developments and distributing unused food.

During the pandemic we saw slivers of this possibility, even in our universities in the States. In Chicago during the pandemic, they created small grants for small businesses that were struggling in the pandemic. They took unused food from the cafeterias and converted it into meals for families of need. My question though is, because we know that the cafeteria had thrown out food every day, why wouldn’t you be doing this all the time?

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "What Universities Have Wrought: An Interview with Davarian Baldwin"

While recognizing this is not about scholarly publishing per se, I would still say this is one of the most important articles The Scholarly Kitchen has published. I just ordered a copy of this book and look forward to a deeper dive into this topic.

US readers may be interested in knowing that the University of Winnipeg’s sustainability initiative began in 2005 with the facilitation of a proposal by then President, Lloyd Axworthy, a former Minister of various portfolios including Foreign Affairs. He was a great politician devoted to public service and was nominated by Senator Patrick Leahy for the Nobel Peace Prize for his work on banning land mines.

I attended Clark University in Worcester, MA in the 1980s. It is a private university, small and without a massive endowment, situated in the Main South neighborhood, the worst in the city in terms of poverty, gang activity and crime due to long term socio-economic decline and urban decay. The university and its c3000 students were viewed with some hostility by the ethnically and racially diverse locals, too.

While I was there, the University began an effort to follow the strategies here, leading to urban gentrification for the purposes of keeping the university attractive to fee-paying students, and even provided incentives to faculty to live there and to patronize local businesses and eventually, schools. They spent $9.5 million in the first phase, buying buildings and restoring them, and helped establish a PPP, Main South CDC. The next phase after I was gone, was the University Park Partnership (UPP) Revitalization Initiative, described here https://www.mainsouthcdc.org/historical-perspective. This and subsequent work, I guess using favourable higher education tax status and with some City support, has involved demolishing and rebuilding a few blocks with a lot of vacant and substandard property, building sports facilities, restoring heritage buildings, and youth work/projects. Some buildings and colorful open spaces and car parks on Main St have now gone, replaced by apartments and university offices. Campus police patrol. The idea has been to create a ‘safe zone’ around campus, and to extend into the surrounding neighborhood. Success has been partial – many decaying wooden three decker apartment buildings remain, and crime has not been eradicated but there are more local businesses serving both communities, aided by startup funds. Almost all the faculty still live elsewhere, the majority on Worcester’s west side. Just a handful -two are my friends – lived locally when I last visited in 2017, some with subsidised housing loans from the university. There has been subsidised university tuition for Main South locals, and the PPP started a school – University Park Campus School, which apparently has low dropout rates. So it’s a localized story, and mixed in terms of its impacts, perhaps not as aggressive and insensitive as some in the book. At root though is a private university trying to make the neighborhood safe and attractive for students, and financially lucrative, with a subsidiary interest in its liveability for the local population. You see similar initiatives elsewhere in the world, but the US leads the way in visceral inner city town/gown divides, social and spatial.

Universities create wealth. Who shares in that wealth is a separate (and important) matter.

As someone who has written history of Making of a national University in India I saw many of the operating elements emerging earlier. I am so glad this book brings them together in an analytic frame. Thanks Prof Baldwin as well as Karin Wulf to bring them to us here.