Editor’s Note: Every year as we enter the holiday season, we take a moment to pause and look back on the best books we encountered (not a “best books of 2022″ list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2022 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new). In recent years we expanded our list to include any sort of cultural creation or experience our Chefs wanted to share.

Here’s Part 1 of our list, Part 2 is also available.

Joe Esposito

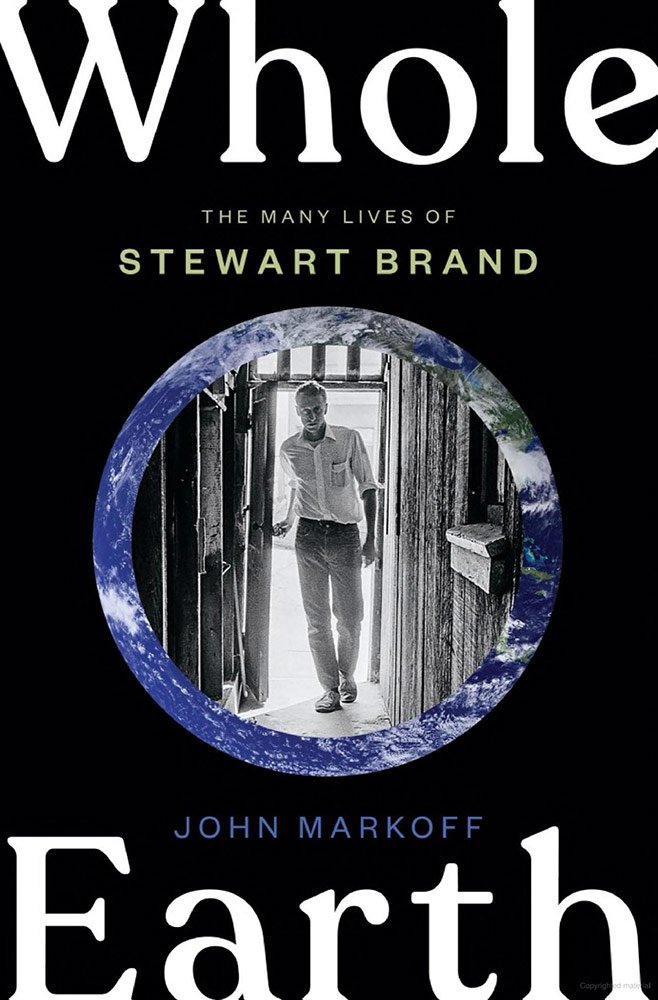

I find that one book leads to another. A few years ago I read John Markoff’s excellent book on the counterculture and the rise of Silicon Valley, What the Dormouse Said. As a major figure in that book was Stewart Brand, the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, I waited eagerly for Markoff’s biography of Brand to appear. It is available now; the title is Whole Earth. Brand was a leader in the creation of the distinctive socially progressive but libertarian ethos of the San Francisco Bay Area. He was everywhere, knew everybody, and developed a number of projects beyond the Whole Earth Catalog. Truly one of a kind. I strongly recommend this book.

I find that one book leads to another. A few years ago I read John Markoff’s excellent book on the counterculture and the rise of Silicon Valley, What the Dormouse Said. As a major figure in that book was Stewart Brand, the creator of the Whole Earth Catalog, I waited eagerly for Markoff’s biography of Brand to appear. It is available now; the title is Whole Earth. Brand was a leader in the creation of the distinctive socially progressive but libertarian ethos of the San Francisco Bay Area. He was everywhere, knew everybody, and developed a number of projects beyond the Whole Earth Catalog. Truly one of a kind. I strongly recommend this book.

Brand was part of the cultish community that gathered around author Ken Kesey (the Merry Pranksters), immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s cult classic, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Markoff’s book nudged me to go back and read the Wolfe book again, which I did, in audio. I last looked at this book when I was a long-haired college student. It is an amazing piece of journalism, and so funny at times that I laughed out loud as I listened to it while walking the dog. But now, as a man of a certain age, I see that Wolfe was not celebrating Kesey’s clan but mocking it. Indeed, I grudgingly realized that Wolfe is basically an unpleasant person. I recommend Kool-Aid with that caveat.

Brand was part of the cultish community that gathered around author Ken Kesey (the Merry Pranksters), immortalized in Tom Wolfe’s cult classic, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Markoff’s book nudged me to go back and read the Wolfe book again, which I did, in audio. I last looked at this book when I was a long-haired college student. It is an amazing piece of journalism, and so funny at times that I laughed out loud as I listened to it while walking the dog. But now, as a man of a certain age, I see that Wolfe was not celebrating Kesey’s clan but mocking it. Indeed, I grudgingly realized that Wolfe is basically an unpleasant person. I recommend Kool-Aid with that caveat.

One book leads to another: Prominently featured in Kool-Aid is Neal Cassady, who drove the bus for the Pranksters. Cassady was manic. He became the model for Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. I thus re-read the Kerouac, after a 30-year hiatus. This is definitely a book worth revisiting; I think it is, after Lolita, the most misinterpreted American novel of all. Thousands of young people hitchhiked across the U.S. inspired by that novel, but, on re-reading, it made me want to check into a hotel with air conditioning. Kerouac silently critiques his narrator, Sal Paradise, who, in turn, begins to see Dean as hopelessly unstable — for example, Sal has to instruct Dean not to touch a 13-year-old girl. The jazz-like prose often skates over the scenes, but Kerouac leaves clues as to the human drama lurking behind the elegant riffs. Like Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, On the Road must be gone through, not around, for any sense of American literature.

One book leads to another: Prominently featured in Kool-Aid is Neal Cassady, who drove the bus for the Pranksters. Cassady was manic. He became the model for Dean Moriarty in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road. I thus re-read the Kerouac, after a 30-year hiatus. This is definitely a book worth revisiting; I think it is, after Lolita, the most misinterpreted American novel of all. Thousands of young people hitchhiked across the U.S. inspired by that novel, but, on re-reading, it made me want to check into a hotel with air conditioning. Kerouac silently critiques his narrator, Sal Paradise, who, in turn, begins to see Dean as hopelessly unstable — for example, Sal has to instruct Dean not to touch a 13-year-old girl. The jazz-like prose often skates over the scenes, but Kerouac leaves clues as to the human drama lurking behind the elegant riffs. Like Huckleberry Finn and The Great Gatsby, On the Road must be gone through, not around, for any sense of American literature.

Allow me to indulge myself and mention one other title, which I just began to re-read for perhaps the sixth time, my favorite book by my favorite author, The Complete Cosmicomics by Italo Calvino. Calvino invented a new genre with these 34 short stories, embedding a human-like consciousness into cosmological phenomena. The physics is fascinating, the humor hilarious, and the insights into human sentiments often moving. If you read only one book — but why in the world would anyone read only one book?

Alice Meadows

This is usually one of the hardest “Ask the Chefs” to answer — there are so many great books out there. But this year, as soon as I read it, I knew that Pip Williams’ The Dictionary of Lost Words would be my choice for both my next book club pick and for this Scholarly Kitchen post! I picked it up by chance in my local bookstore, couldn’t resist a blurb that begins, “Esme is born into a world of words…” and read it pretty much in a single sitting.

This is usually one of the hardest “Ask the Chefs” to answer — there are so many great books out there. But this year, as soon as I read it, I knew that Pip Williams’ The Dictionary of Lost Words would be my choice for both my next book club pick and for this Scholarly Kitchen post! I picked it up by chance in my local bookstore, couldn’t resist a blurb that begins, “Esme is born into a world of words…” and read it pretty much in a single sitting.

The Dictionary of Lost Words is set mostly in late nineteenth/early twentieth century Oxford, and the story is woven around the development of the first Oxford English Dictionary (OED). Like all the best historical novels, it’s a clever blend of fact and fiction. Having worked as a freelancer on the Concise Oxford English Dictionary in the late 1980s, I found it astonishing how similar the process of “collecting” words and definitions on handwritten postcards was nearly a century later (admittedly pre-Internet!). I also loved how recognizable the Oxford of then is to the Oxford of now — for example, the protagonist, Esme, and her father live on Observatory Street, just around the corner from what is still the Oxford University Press building. Many of the characters are also either real (the Dictionary’s editor, James Murray, for example) or based on someone real (Esme’s godmother, Ditte, based on real-life OED volunteer, Edith Thompson). So, too are the events and issues the book covers, including some, like backstreet abortions and voting rights, which suddenly seem all too real again today.

The title of The Dictionary of Lost Words essentially sums up the overall theme of the book itself. When Esme realizes that the men involved in collecting words for the OED are ignoring (or even deliberately rejecting) some that are commonly used by women and/or less well educated people, she decides to take matters into her own hands and collect these lost words herself. It’s a courageous thing to do for all sorts of reasons, and brings Esme into contact with many people she would otherwise never have met — and into conflict with some of those she is closest to, especially when she has to decide what to do with her collection of lost words. I loved the fact that the inspiration for the book was the author’s discovery that the word “bondmaid” was missing from the first volume of the OED when it was published in 1901 — and no one knows why or how. Bondmaid is also the first word that Esme realizes is missing, and so her journey into the world of lost words begins.

Pip Williams writes beautifully and tells a fascinating story. I absolutely loved The Dictionary of Lost Words and so does everyone I’ve recommended it to (it also prompted the longest discussion about a book we’ve ever had at my book group!). I very much hope you will too.

I would venture a guess that the majority of people reading The Scholarly Kitchen, and almost everyone reading a post of book recommendations, could be described as “book people”. We all might love different types of books, different types of stories, or different styles of written communication. Since the start of the pandemic, I’ve made it a goal to increase my book consumption, which had languished in recent years in favor or reports, articles, Twitter or other work-related content. It has been a joy getting back to consuming a variety of books on a monthly basis. This year, interestingly, I’ve spent a great deal of time reading about reading, about the history of books, about how we understand books, and how machines understand books.

I would venture a guess that the majority of people reading The Scholarly Kitchen, and almost everyone reading a post of book recommendations, could be described as “book people”. We all might love different types of books, different types of stories, or different styles of written communication. Since the start of the pandemic, I’ve made it a goal to increase my book consumption, which had languished in recent years in favor or reports, articles, Twitter or other work-related content. It has been a joy getting back to consuming a variety of books on a monthly basis. This year, interestingly, I’ve spent a great deal of time reading about reading, about the history of books, about how we understand books, and how machines understand books.

With this increased volume, it is interesting to deeply reflect on the world of books, both in the libraries and in the book trade, in which many of us work. Earlier this year, at the Book Industry Study Group annual meetingin NYC, each attendee was given a new book. I picked up a copy of In Praise of Good Bookstores by Jeff Deutsch, published by Princeton University Press. It is a glorious, philosophical treatise on the values, structure, and importance of bookstores as cultural institutions. Deutsch is the director of Chicago’s Seminary Co-op Bookstores, which in 2019 he helped incorporate as the first not-for-profit bookstore with the mission of bookselling, and this background infuses his text with a clarity of vision and purpose. Being “book people”, I expect most of you embrace and relish in the joys of a good bookstore. From the possibilities inherent in the size of the offering, to the care and organization of the objects, to the contemplative browsing of the others who share the space, I often experience the thrill and serendipity of a visit to a bookstore, be it my local bookseller or a new find on my travels.

The book explores the bookstore as a physical space, as a place of curation, of abundance, of value, and of community. In it, the author reflects as much on the literature contained in the bookstore and its relevance to culture as he does to the process and business of book sales themselves. From his calculation of the number of books one could possibly read and how many he had left to possibly read, to the interesting details of the sale of books—such as of all the books sold by the Seminary Co-Op, some 60% were single-title sales, sought by a unique reader—one is delighted by his thoughtful consideration of this segment of our community.

The comparisons and similarities between the world of bookstores and libraries was so strong throughout and I often found most of the descriptions could have been aptly replaced one word for the other, and one that Deutsch often connects. The two institutions serve similar purposes and, as Deutsch described them, similar roles in our society. Filled not only with reflections of his own extensive reading, and his experience running bookstores, he connects the process of collecting and sharing knowledge through space and time, both as a business, but also as a calling some are drawn to. I expect many of you reading this will see some reflection of yourselves and your own calling in the process of sharing content in Deutsch’s writing, as I did.