A recently published survey of scholarly authors reveals a growing acceptance of the benefits of open access publication, yet authors are still wary of unfettered and commercial reuse of their work.

The 2014 Taylor & Francis Open Access Survey updates and expands upon their 2013 study. Juxtaposing the results of both surveys allowed the researchers to identify potential trends over time. We should reserve a little caution with interpreting some of the changes since there may be evidence of sampling or response bias between the two surveys.

For example, while the 2014 survey received nearly 8,000 responses (a 9% response rate), it was nearly half of the response size of the 2013 survey, which reported a 19% response rate. The demographics of the two response groups also appears to be somewhat dissimilar. Compared to 2013, 2014 respondents were measurably younger (median age 43 versus 46), included more women (39% versus 35%), far fewer full professors (20% versus 26%) but many more assistant professors (16% versus 13%). These differences do not invalidate the comparison, only that readers should be aware that changes in author responses may simply reflect the dissimilar composition of these two response groups.

Taylor & Francis authors believe that open access offers wider circulation, higher visibility, and larger readership than publication in subscription journals (Q1). For all three of these questions, 2014 respondents selecting strongly agreed increased from 2013. Similarly, 39% of respondents strongly disagreed to the premise that “there are no fundamental benefits to open access publication” up from 30% in 2013 (Q2).

And while there appeared to be mixed responses when an author’s work is utilized for text or data mining, translation, adaptation or inclusion in an anthology, authors were largely against the use of their work for commercial gain (Q5). The majority of respondents (71%) were fine with non-commercial use of their work, however.

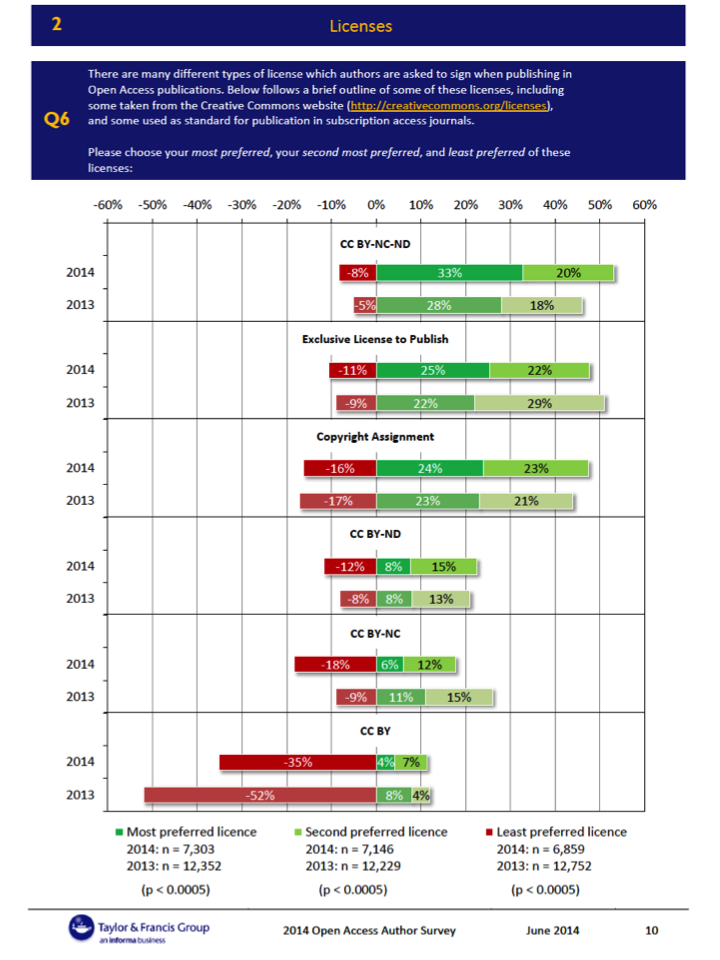

Authors are also still leery of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which permits users to “distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon” a piece of work as long as the creator of the work is credited (Q6). While the CC BY license was consistently rated as the least preferred license in both surveys, aversion to the CC BY license appears to be softening: 35% rated CC BY as their least favorite license in 2014 compared to 52% in 2013. It should be noted that CC BY permits an article to be republished anywhere for any commercial purpose–a surprise that came to several PLOS authors last year.

In contrast, the most preferred license by respondents was again the CC BY-NC-ND, a restrictive license that prohibits derivative and commercial use. Thirty-three percent of respondents selected CC BY-NC-ND as their most preferred license in 2014, up from 28% in 2013.

While framed within the context of open access publishing, the Taylor & Francis survey included questions about peer review and submission preferences (Q8). Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of respondents preferred a form of peer review that included an assessment of the merit and novelty of their results. Other flavors of peer review, such as those used by eLife, PLOS ONE and F1000 Research, received support by fewer respondents, although their numbers appear to be rising. I do wonder if the responses would come out differently if the questions were posed a little differently. For example, peer review with rigorous assessment came with a caveat (“even if this takes a long time”), while the other forms of peer review avoided listing any risks, costs, or biases.

The last question that caught my attention was to have authors rate the importance of services they expect with open access publishing (Q13). Personally, I don’t feel that any of these questions are limited to open access per se; nevertheless, they seem to reaffirm what most authors want from journal publication:

- Rigorous peer review

- Rapid publication of my paper

- Rapid peer review

- Promotion of my paper post-publication

- Automated deposit of my paper (Author Accepted Version) into a repository of my choice

- Provision of usage and citation figures at the article level

- Detailed guidance on how I can increase the visibility of my paper

- Pre-peer review services such as language polishing, matching my paper to a journal, and / or formatting my paper to journal style

- Provision of alt-metrics (such as Altmetric or ImpactStory)

What surprised me from the results was that alt-metrics ranked dead last. In 2014, 38% of respondents rated the the provision of alt-metrics as either very important (5) or important (4) on a Likert scale, down from 45% in 2013. Are authors still confused with this term or does “alt-metrics” convey a negative connotation? The fact that the composition of the 2014 respondent pool was younger, less senior and more female implies that the next generation is responding much more conservatively than its predecessors. Likewise, it suggests that new publisher services, such as accessibility on mobile devices, may be more importance to publishers than to their authors.

Correction (6:45am): The original post listed some incorrect dates for both survey and publication dates. Thanks to Joanna Cross at T&F for spotting them.

Discussion

45 Thoughts on "Open Access Publication Gains Acceptance With Authors, Licenses Still Problematic"

Thanks for this helpful and accurate summary. I enjoyed the irony that Taylor and Francis helpfully chose to publish the report itself under CC By, perhaps suggesting that they understand its benefits better than some of their authors! 🙂

Perhaps T&F employees are subject to a different career structure and pressures than academic researchers?

Or perhaps they’ve just given more thought to the actual consequences of the licences?

I don’t know that you can make a simple 1:1 comparison between a commercial publisher doing a study (likely as a promotional effort to raise their profile in the OA world) and a researcher cautiously looking both to control his/her own reputation in a reputation-based career structure and to limit others from profiting from his/her work. The nature of the work, the motivations of the authors and the environment in which it is being published are entirely different.

They are different, yes; but much the same pressures and misapprehensions act in both cases. The most pernicious of these is that the NC clause is attractive because people interpret it as “if someone figures out a way to make money using this they have to give me a cut”, whereas in practice it means “people who have any chance of making money won’t use my work”. I’ve made this mistake myself, many times — it’s a very natural one. But my observation has been that the more people think about the implications of licences, the more they tend to move towards more liberal licencing of their own work.

I don’t see the NC clause as being about researchers looking for a cut of profits from reuse of their work. I think it’s more about control of reputation and the avoidance of sleaze merchants. Basically, if you want to reuse my work and my name, I want to make sure you’re on the up and up before granting permission. Similarly the ND clause offers a chance to control how your name and reputation are used–if someone is going to change the work and still attribute it to you, wanting to have oversight on what’s being done in your name seems reasonable to me.

NC and ND licenses don’t prevent commercial exploitation nor do they prevent derivative works. They do require permission though, and given how much of academic funding and career advancement is reputation-based, it’s not surprising that researchers want to have as much control over how their names and reputations are being used. If this means that those who can’t be bothered to ask permission to reuse the work won’t reuse it, that’s probably an acceptable compromise.

I don’t see the NC clause as being about researchers looking for a cut of profits from reuse of their work. I think it’s more about control of reputation and the avoidance of sleaze merchants.

For whatever little it’s worth, that doesn’t correspond with my observations. What I see is that NC is adopted basically from a fear of missing out. But all that happens as a result is that everyone misses out.

If someone is going to change the work and still attribute it to you, wanting to have oversight on what’s being done in your name seems reasonable to me.

You don’t need an NC clause for that: CC By is very clear: “You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.”

NC and ND licenses don’t prevent commercial exploitation nor do they prevent derivative works. They do require permission though.

Yes. (To be precise, the incorporation of NC and ND does prevent commercial exploitation and derivative works under that CC licence. Someone wanting to make commercial use or create a derivative is simply tossed back to the default “all rights reserved” state and is free to negotioate with the copyright holder just as he would with a copyright holder that had not used a CC licence at all.

The problem is, as anyone who’s been involved with content-mining will tell you, that obtaining such permission is a huge time-sink, and can become a full-time job on its own. Most potential re-users, most of the time, will simply look at all that friction, think “forget it”, and do whatever they’re going to do with other works instead — ones that don’t need them to jump through hoops.

And this is perfectly reasonable. When you want images to put on this blog, I’m sure you do what I do, which is search Google or Flickr for something that is freely available for the use you have in mind. You don’t pick a copyright-encumbered licence and enter negotiations with the copyright holder. Why would you? There’s so much content out there!

If this means that those who can’t be bothered to ask permission to reuse the work won’t reuse it, that’s probably an acceptable compromise.

I think it’s rather a sad outcome.

Maybe paleontologists are a particularly greedy bunch 🙂

But I don’t see the Biology and Medical researchers I work with expecting to make a lot of money from their papers (or books/book chapters for that matter). For those doing work with immediate practical application, any expectation for revenue comes from patents, not from copyright, from discoveries, not from the words written about those discoveries.

But I do agree that these sorts of licenses are problematic for those doing widespread content mining. The good news is that copyright reform (in the UK for example) and awareness of text and data-mining needs are improving things in this area, at least for noncommercial research purposes. It’s still a problem though in terms of commercial reuse though. But I’d rather err on the side of creator rights than the rights of the secondary exploiter, and if you’re hoping to profit from a large scale redistribution and resale of someone else’s work, then I don’t have too much of a problem asking you to license those rights or at least ask permission.

Certainly not true for OA monograph publishing. I haven’t seen one yet that uses just a CC BY license. The new AAU/ARL initiative does not, for instance, as it contemplates presses making money out of selling POD editions.

Hi Sandy – just seen this comment. Our first OA monograph was funded by the Wellcome Trust last year – http://www.palgraveconnect.com/pc/doifinder/10.1057/9781137377029 – and it was published under a CC BY license.

We offer CC BY open access monographs as the default option, although other licenses are available on request.

Amy Bourke

Palgrave Macmillan

Amy:

Journal costs are rather public. If you are allowed, what were the fees for the book?

Hi Harvey

No problem, our APC prices are public too. The APC for an open monograph is £11,000, which was paid by The Wellcome Trust. The book is published as an ePub via online retailers such as Amazon Kindle, and via PDF on Palgrave Connect, our own platform. It’s also published in XML on PubMed Central, due to their relationship with the Wellcome Trust. We don’t charge for any of these.

Are your authors not concerned that with this license they have no control whatsoever over translations made of their books? Does Palgrave itself not worry about shoddy translations being made of the books it publishes?

It will be interesting to see what Amy has to say about this, but speaking as the author a large body of CC By work, I am much more worried about the lack of translations than about the possibility that someone might make a translation that is less than perfect. I’d much rather someone make a suboptimal translation of my writing than that no translation be made. (I guess this comes back to Tim O’Reilly’s aphorism that for most artists the problem isn’t piracy, it’s obscurity.)

Interesting, Mike, and that is your choice–or it should be your choice and not something mandated by anyone else. I think, though, you may feel differently if you have a bad experience with a translation or other use of your material that you don’t review and authorize yourself. I hope you never have that experience.

Hi both

We provide open access monographs, and the CC BY license, because our authors and some funding bodies have told us they would like these options available. Other licenses are available too. The publication of our first monograph was covered by the Chronicle of Higher Education’s Wired blog at the time, which might interest you: http://chronicle.com/blogs/wiredcampus/wellcome-trust-palgrave-macmillan-publish-their-first-open-access-monograph/48415

Thanks, Joe. In fact I have had experiences like this once or twice; but I consider them a price well worth paying for the extra reach a liberal licence gets me. (And I suspect that most of the bad things that have happened to my CC By blog-posts would have happened even if they’d been all-rights-reserved: things like those sites that automatically plagiarise from well-known places and scrub the attribution.)

On choice: you may be surprised to hear that I do agree that authors should have the choice of how (and indeed whether) their work is distributed, up to and including all-rights-reserved or lock-in-a-safe-until-dead. So long as it’s work that the authors have done on their own time, at their own expense. As soon as someone else is paying them to do it, all bets are off and it’s down to the contract that the author and employer agree.

And did you read my comments on that Chronicle story? I can’t help wondering whether all your Palgrave authors really understand the consequences of what they are signing. It appears from other anecdotes I’ve heard that some authors are shocked to find out what they have given away. By the way, the clause about distortion, etc., no longer appears in the most recent versions of the CC-BY license, so even that minimal protection is gone. The current CC-BY license simply refers to the fact that “moral rights” may be recognized in some countries’ legal systems. They are not in the U.S., except for a very narrow slice of visual art.

“I can’t help wondering whether all your Palgrave authors really understand the consequences of what they are signing.”

That’s exactly what I ask myself when I see that someone has chosen CC By-NC-ND (or indeed all-rights-reserved or copyright transfer).

“By the way, the clause about distortion, etc., no longer appears in the most recent versions of the CC-BY license.”

The licence says “You must […] indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use.” Seems clear enough to me. The CC By licence doesn’t for example, allow creationists to reuse my palaeontological work in a way that suggests I endorse creationism.

I would not bet the farm on creationists not using your words to endorse their position.

“I would not bet the farm on creationists not using your words to endorse their position.”

Of course they will — unscrupulous people do unscrupulous things. The point is, the CC By licence doesn’t allow them to do that more than CC By-NC-ND or all-rights-reserved would. They do it despite the licence rather than because of it; and if I had, the money, time and will to pursue them through legal channels, then the CC By licencing of the original would not be a defence for them.

That’s not the language I was referring to, Mike, and that doesn’t apply to translations anyway. You have zero protection against bad translations, even ones intentionally produced, in countries that don’t recognize moral rights. You may not be so concerned about this as a scientist, but I’m willing to bet that many humanities scholars are. I don’t think it’s any accident that the AAU/ARL Task Force is proposing the more restrictive license or that the Amherst College Press is using that one also.

if I had, the money, time and will to pursue them through legal channels…

Perhaps one difference is that if the paper had been published under traditional copyright, you would likely have the backing of your publisher whose lawyers would pursue the matter for you. Copyright gives a publisher financial reason to go after miscreants. Do you know if any fully OA publishers strictly using a CC BY license provide similar services to authors if their work is misused against the terms of the license? Did PLOS take any legal action on behalf of authors against that book publisher who collected and sold their papers and didn’t properly attribute?

David: You bring up a good point. The protections a publisher provides are never needed until they are! I discovered that a book I had published was on the web in its entirety. The company immediately issued a cease and desist order and an injunction. The book came down in moments.

My opinion of OA is far from favorable. Sure the article is available for free but I am not so sure the trade off is in the best interests of the author. The author loses protections and the possibility of a company going under and the archive being lost exists. The reason for the costs involved in subscription based materials are often not seen.

To be fair, most fully OA articles are simultaneously deposited in separate archives like PubMed Central, institutional archives, etc. In addition, reputable OA publishers use the same archiving services for their articles as commercial publishers (Portico, LOCKSS, CLOCKSS, etc) so the risk of an article disappearing is pretty minimal.

“Perhaps one difference is that if the paper had been published under traditional copyright, you would likely have the backing of your publisher whose lawyers would pursue the matter for you.”

In principle, at least, this is a difference between blogging and formal publication, not between CC By and all-rights-reserved. The reason no-one goes after these plagiarists isn’t because of the licence in use, but because it’s not worth anyone’s while (certainly not mine).

“Copyright gives a publisher financial reason to go after miscreants.”

That is true.

We would hope that publishers would also do things for reasons other than financial. But:

“Do you know if any fully OA publishers strictly using a CC BY license provide similar services to authors if their work is misused against the terms of the license?”

I don’t know, and would welcome comments from people who do.

“Did PLOS take any legal action on behalf of authors against that book publisher who collected and sold their papers and didn’t properly attribute?”

You’re referring to the Apple Academic Press misbehaviour?. I’ve not heard of PLOS taking any legal action, no (though of course that doesn’t mean it hasn’t happened).

Creative Commons itself has been engaged in a campaign to change perceptions of CC-BY. At http://creativecommons.org/choose/ your choices are labeled. If you choose CC-BY-NC, your label is “This is not a Free Culture license.” If you choose CC-BY, your label is “This is a Free Culture license.”

One has to wonder why Creative Commons shifted from a neutral position to advocacy. Perhaps there were real or imagined strings to the future of CC funding. http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/10001

Has Creative Commons ever been seen as a neutral player? It has always seemed clear to me that they exist to advocate for a particular IP agenda.

Mike: I find your reply interesting regarding making money off of ones journal publishing. I know of no scientific author who goes into the publishing game to make a buck. I would often advise that if you expect to make money I urge you to flip hamburgers because you will earn more in a shorter length of time.

The problem with using the free stuff out there is the time required to find it not to mention that it may not exist. Time is money!

This is how Taylor & Francis portrays what it calls the “2014 Open Access Survey”:

“In the first few months of 2014 Taylor & Francis carried out a worldwide survey, with the aim of exploring journal authors’ views on open access. Having previously conducted a survey on open access in 2013, we have been able to see how authors’ opinions have developed, and whether the discussion and debate on open access has helped to inform and shape views. With responses to both the 2013 and 2014 survey given side-by-side, you can easily see how attitudes have changed. Alongside this, the 2014 survey explores many new areas and gives a fascinating insight into authors’ current perceptions of open access.”

However, when you look at the methodology, the survey was, as Phil points out, conducted in 2012. The title of the survey gives the wrong impression, and this write up I copied from their site (http://www.tandfonline.com/page/openaccess/opensurvey/2014) really gives the wrong impression.

This should be called the “2012 Open Access Survey.”

It leads me to wonder why it takes them two years to process SurveyMonkey results.

My reading of the methodology is that the survey was conducted in 2014, but those surveyed were authors who had published papers with T&F in 2012:

The 2014 Taylor & Francis Open Access Survey was sent to authors published during the year 2012 (the subsequent year to the 2013 Taylor & Francis Open Access Survey, which was sent to all authors published during 2011), who had not previously opted out of receiving surveys sent by the Research and Business Intelligence Team.

I see no indication that the survey took place in 2012. It is perhaps worth noting that those surveyed were limited to authors who published in T&F journals, not all authors worldwide. Given their recent launch of Cogent, one wonders how much of an effect that will have on future studies, and whether it’s possible to compare those with the current ones.

The problem I have with surveys is in their application. At best, like this one is trying to learn about a moving target. One can base some decisions on it, but one has to be very careful in its application.

I think one of the most revealing findings about surveys was demonstrated in Karl Rove’s reaction to Ohio!

The differences in responses re: altmetrics may have to do with wording: in the 2013 survey, the question re: altmetrics is phrased as “Provision of article metrics in addition to usage and citation, such as Altmetric or ImpactStory”, whereas in this year’s survey, they ask about “alt-metrics”.

This is relevant because as a recent Elsevier survey, led by Michael Habib, has shown us, the term “alt-metrics” doesn’t necessarily resonate with researchers, but the concept does.

So a couple of points regarding the ranking of altmetrics:

1. Yes researchers still don’t understand the term. I first presented the survey results Stacy refers to at the 2013 SSP conference (http://mchabib.com/2013/06/27/summary-slides-for-2013-ssp-panel-measure-for-measure-the-role-of-metrics-in-assessing-research-performance/ ) and gave an update later that year at the at the second in-person meeting for NISO’s Alternative Metrics project (http://www.slideshare.net/BaltimoreNISO/habib-niso-altmetrics-dec-2013 ). The surveys were conducted by Elsevier’s Research and Academic Relations group (full reference in the slides).They show that from Oct. 2012 to Oct. 2013 awareness of altmetrics (the term) rose from 1% to 5%.

2. The results also show that perceived value of a (named) metric correlates to awareness (NISO presentation slide 7). For altmetrics we can see that Scopus users both have a higher awareness (10%) and a higher perceived value of altmetrics (NISO presentation slide 8).

3. The survey results also ask the questions a different way by asking the perceived value of different types of altmetrics (e.g. Number of readers). When the questions were phrased around the individual metrics, younger researchers showed significantly higher interest than more senior researchers. (NISO presentation slided 9).

4. As Stacy mentions, in the 2013 Taylor & Francis study, the primary question was phrased as provision of article-metrics and then in 2014 as provision of altmetrics. If researchers are more aware of article-metrics the term, then that could explain the change. PLOS users would, for example, most likely not know the term altmetrics but may be familiar with article-metrics. That said, the 2014 survey says that a definition box for altmetrics was presented. Without seeing how obvious that definition box it can be hard to know if the change in wording effected the outcome.

5. As Phil mentioned, but worth repeating, these services apply to all journals. Altmetrics aren’t just for OA. Getting into definitions in the survey, altmetrics aren’t just article-level either. Just like citations than can be rolled up at any level.

_

Michael Habib

Sr. Product Manager, Scopus at Elsevier

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-8860-7565

I would love to see a pan-publisher author survey on OA – while individual publisher surveys like this are always interesting, I fear that survey fatigue is setting in (hence substantially lower response rate this year – we’ve experienced the same thing at Wiley); carrying out a single survey annually would surely help. And it would also give us a view of what the whole author community thinks rather than just one section of it, which would be very valuable

I don’t think I missed it– although there is a demographic profile of the respondents (12% in the humanities for 2014 vs. 9% in the 2013 survey), there is no reflection of discipline specific responses to the questions. This is awfully important.

This is indeed important – as our analysis last year showed. After we released the top-level report in 2013, I produced a further ten Supplementary Reports (http://www.tandfonline.com/page/openaccess/opensurvey/2013) which analysed each of the key areas of the survey responses by subject, country, global region, age and professional status.

We are currently investigating the best way to share a similar analysis for the 2014 Survey results. However, in the meantime, we wanted to release the top-level report as soon as possible.

Our focus in the coming weeks will be the responses to the country-specific questions about National Open Access Mandates in the United States, the United Kingdom and the European Union.

I have issued an updated report (available at the same URL) with a minor alteration to the Survey Methodology section, to clarify that we sent the 2014 Taylor & Francis Open Access Survey to our authors throughout the month of March 2014.

Additionally, we have made all of the individual charts available on FigShare to make it easy to share a particular result:

http://figshare.com/authors/Open_Access_Taylor_Francis/589654

We also plan to release a Supplementary Report that breaks down the responses to key questions by the Career Stage of the respondent as given in the final question of the survey, Question 26.

Thanks for this, Will. I think the way T&F have gone about this has been exemplary: careful explanation of the statistics, liberal licencing, quick fixes when ambiguities are pointed out, and individual elements easily available. Excellent job!

BTW., although there have been some comments on this thread rightly pointing out necessary weaknesses in the study itself, I think some commenters have been quick to overlook the most important aspect of what the survey tells us, which is how attitudes are changing. It’s really helpful to have this documented.

Reblogged this on A librarian abroad and commented:

Always great content at Scholarly Kitchen: very interesting to see what authors want from journal publishers, and that attitudes to altmetrics are fluctuating.