A few days ago, the New York Public Library did something truly remarkable: it made nearly 200,000 digitized photos, postcards, maps, and other images freely available online.

“But wait,” I hear you cry. “What’s so remarkable about that? Sure, that’s a lot of images, but libraries have been digitizing public-domain documents and making them freely accessible for years. Millions of such documents can now be found online. What makes this project so unusual?”

Two things set the NYPL project apart from other, similar digitization initiatives:

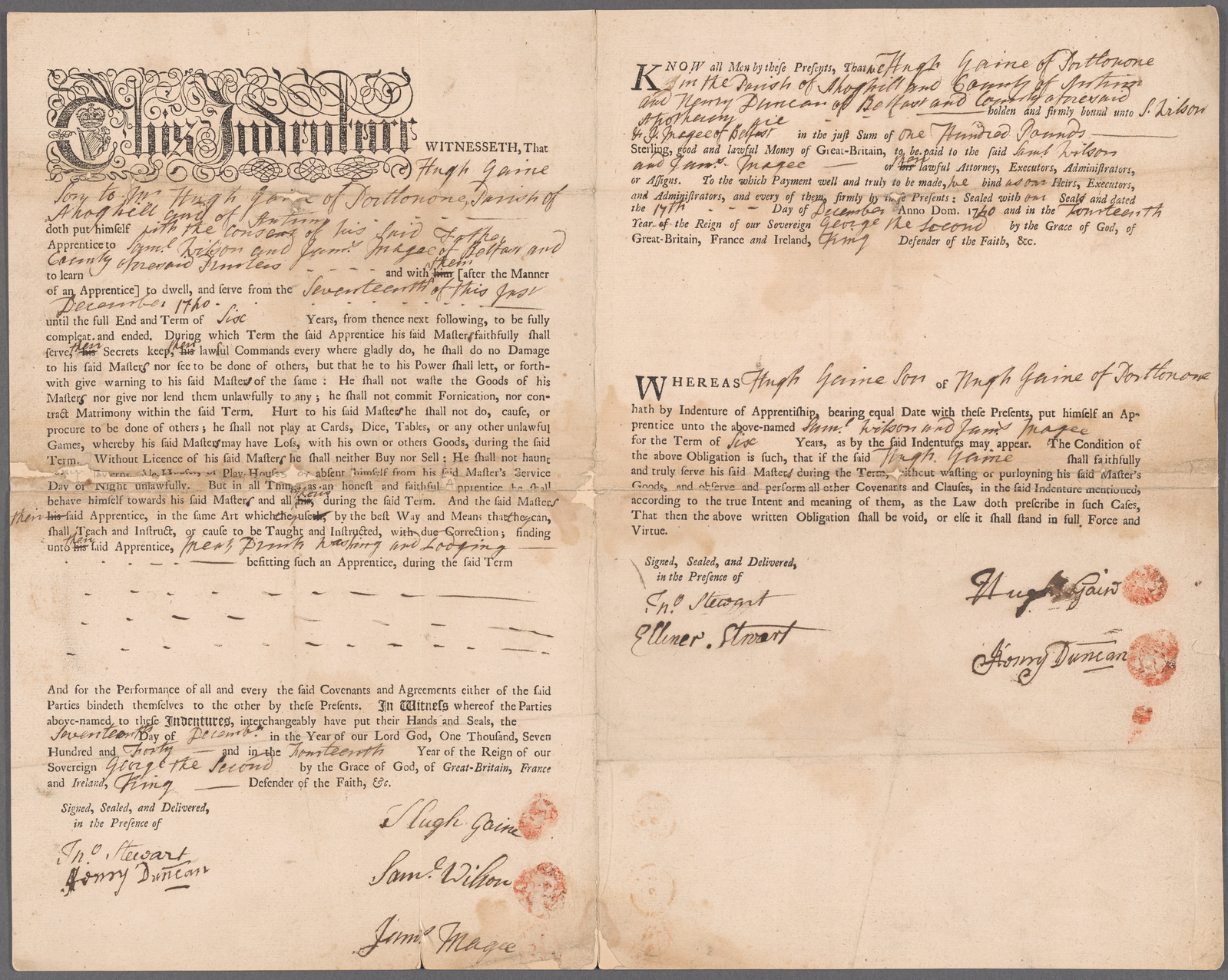

First, the content itself. The NYPL is, obviously, not just any library. Its collection of rare and unique historical documents is unusually rich, and is of unusually broad interest. According to the project’s website, among the materials included in this release are:

- Berenice Abbott’s iconic documentation of 1930s New York for the Federal Art Project

- Farm Security Administration photographs by Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Gordon Parks, and others

- Manuscripts of American literary masters like Walt Whitman, Henry David Thoreau, and Nathaniel Hawthorne

- Papers and correspondence of founding American political figures like Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison

- Sheet music for popular American songs at the turn of the 20th century

- WPA-era lithographs, etchings, and pastels by African American artists

- Lewis Hine’s photographs of Ellis Island immigrants and social conditions in early 20th century America

- Anna Atkins’ cyanotypes of British algae, the first recorded photographic work by a woman (1843)

- Handscrolls of the Tale of Genji, created in 1554

- Medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts from Western Europe

- Over 20,000 maps and atlases documenting New York City, North America, and the world

- More than 40,000 stereoscopic views documenting all regions of the United States

This is an amazing trove of images and documents—not only for students and researchers, but for anyone who just wants to spend an enjoyable few minutes or few hours browsing through beautiful and fascinating historical information.

The second thing that sets this initiative apart from many others is the fact that the NYPL has decided that it is going to treat these public-domain images like what they actually are: public intellectual property that can be reused by members of the public in any way they want.

To be very clear about what “public domain” means: it does not mean that the NYPL holds the copyright in these images and has granted the public a generous reuse license. The fact is that these images are not subject to copyright at all. That means that, even if it wanted to, the NYPL would not have the legal standing to restrict public reuse of these materials.

So if these images are public property anyway, and if the NYPL has no right to restrict their reuse, why do I find it praiseworthy that they’re declining to impose restrictions? Are they doing anything special by simply letting the public make unfettered use of these public-domain documents?

Unfortunately, yes.

A little over a year ago, I wrote about this issue for Library Journal’s Academic Newswire. In far too many libraries, public-domain documents and images are treated as if they were under copyright — and, even worse, in many cases the policies in question are written as if the holding libraries were themselves the copyright holders. Sometimes this is because the librarians who control access to those images genuinely don’t understand copyright law: they believe that simply digitizing an image results in a copyrightable document (it doesn’t), or that owning the physical item gives one legal say over how its intellectual content can be used (also untrue). The result is that in many academic libraries, intellectual content that the public has a right to access, copy, adapt, and generally reuse in any way we wish is being locked down and restricted by — ironically enough — librarians.

What do these restrictions look like? They generally take the form of “permission to publish” policies (a few representative examples of which can be found here, here, and here), which require patrons to request the library’s permission before republishing content from documents in the libraries’ special collections, regardless of those documents’ copyright status. In a few of the more egregious cases, patrons are actually required to ask the library’s permission before even quoting from these documents, and must tell the library where and how they plan to publish the quotes.

Now, it’s important to bear in mind that a variety of factors may limit the ways in which a library can provide access to digitized materials. Low-quality digitization is cheap and easy, but high-quality digitization is labor-intensive and expensive, as is the creation of good metadata. A library might make only low-resolution images available online simply because that’s the best it can afford to do, at least in the short term. It’s also true that not all rare and unique materials are in the public domain, and that donor restrictions may make it impossible for the library to provide free and unfettered access to some public-domain materials. Where circumstances like these prevail, and where the resulting restrictions don’t go beyond what is required by law or donor conditions, I have no criticism.

It’s also true that most libraries are under no legal requirement to share their collections at all, and a library is completely within its legal rights to say, for example, “If you want to enjoy ongoing access to our special collections you must abide by a set of rules that include refraining from fully exercising your legal rights with regard to these public-domain materials.” There’s nothing illegal, in other words, about imposing permission-to-publish policies on documents in the public domain, anymore than it would be illegal for a library to say “You may only enter our special collections reading room if you’re wearing a purple shirt.”

However, it strikes me as perverse that any library would intentionally try to stop the public from making free and full use of intellectual property that is, by law, theirs to do with as they please. By declining to impose such restrictions, the NYPL has already made possible several new information products and tools — and, in fact, it has created a “Remix Residency” specifically to encourage such reuse and reinvention.

I hope academic libraries everywhere will see the NYPL’s example and follow it.

Discussion

25 Thoughts on "NYPL Shows Academic Libraries What "Public Domain" Means"

This is a huge step forward and real leadership by NYPL. Rick, thank you for highlighting this important development for Kitchen readers.

The Library of Congress began doing this way back in the 1980s with its American memory Project championed by James Billington. The HathiTrust group has been doing this for almost two decades now. Were there any restrictions imposed on use of digitized materials from these projects?

Art museums, of course, have long controlled access to works of art in the public domain so that images cannot be made or used by anyone except a photographer authorized by the museum to make the images and users licensed to reproduce them. An important copyright case in the Second Circuit (Bridgman Art Library v. Corel, 1999) did determine that a regular photograph of a public-domain work of art was not “original” enough to claim a separate copyright.

Some works in the public domain can still be under copyright protection in those countries that recognize the “moral rights” of authors, which are perpetual.

The Library of Congress began doing this way back in the 1980s with its American memory Project championed by James Billington. The HathiTrust group has been doing this for almost two decades now.

You’re correct; the same can be said of Digital Public Library of America. But my observations and concerns are about policies in academic libraries, and none of these is an academic library.

But HathiTrust is an aggregation of mostly academic libraries, is it not?

Not exactly. It’s a “partnership of major research institutions and academic libraries.” It is not, itself, an academic library. Even if it were, I wouldn’t be sure what your point is. There are academic libraries out there that are doing what NYPL is doing — my point is that they seem to be the exception to the rule, and that’s the problem under discussion here.

Indeed, NYPL’s lovely navigation section includes a “Show Only Public Domain” check box under Filters. I checked from curiosity about how they’d handled Mark Twain materials at the Berg, some of which remain protected by copyright. The SLC collection shows 863 results until you tick that box–and then there’s only one result.

The problem is bigger than you know. I’m aware of at least 5 “entrepreneurs” who are working to contract with academic libraries to digitize large parts or all of their media collections (pictures, photos, movies, videos, etc) and then hold those digitized products “in lieu of” the library. And will charge a fee for each access and most particularly a higher fee for publication use. Google so far has not jumped on this bandwagon, But their entry seems likely. And they already know the libraries and the researchers/students who depend on them. So the next public domain media publication request for a dissertation or faculty research project could see another $100 to $500 added to the cost of the work. That’s capitalism! Or at least the neoliberal version of it.

It would be interesting to know more details about these proposed programs. Can you share anything further? (Generally, I try to be careful not to get too outraged about things like this until I have verifiable facts in hand.)

I must disagree with you, Ken. While I don’t know the details of the projects you mention, the reason that third parties are getting involved is because no one is willing to fund the digitization process and make things available for free. I really don’t think you understand what the public domain is. No reason in the world not to charge for access. Access and copyright are different things.

Joe, I would disagree with you only if Ken is right about these initiatives resulting in some entity holding truly unique public-domain documents “in lieu of” the original holding library and charging people for access to them. If, in fact, this is what happens, then it seems to me it would constitute taking public-domain content functionally out of the public domain.

I’m skeptical, though, that this is exactly what’s being contemplated in these initiatives. Hence my desire for more verifiable details.

Your use of the word “functionally” seems right to me. But I would counter with this point: if these materials should be available to everybody, why won’t people pony up the money to do the job? This is a constraint refrain–that is, that commerce is taking things away from The People–and it is not restricted to scholarly communications. For example, there is much moaning about the destruction of the old Penn Station in New York, but if it were so valuable, why would people pay to keep it?

I can’t speak for Ken, but my concern isn’t really primarily about availability — after all, as I pointed out, access will always be limited by the resources available for making access possible, which is why no library has yet digitized all of its rare/unique holdings. My concern here is with libraries that, having made public-domain content accessible, then try to restrict the reuse of that content.

The question you’ve posed here is probably a good topic for a whole separate posting.

Here is a site that promises to teach you about how to profit from selling public-domain materials: https://www.udemy.com/repurposing-public-domain-content-for-beginners/

A friend of mine used to find, republish, and sell 19th-century books on railroad history. Seems completely fine and legitimate to me. He wasn’t restricting anyone’s access to the source documents he used, nor did he try to stop anyone else from reusing those source documents in whatever way they might wish. Similarly, it’s not at all unusual for a library to sell prints of digitized public-domain photos from their special collections. I see no problem at all with that — as long as the library doesn’t try to stop other people from making and selling prints of those photos as well.

Rick, we can toss this over to the copyright nerds, but the original source document is not in the public domain. The text is. You can lock up the source document or burn it. Not a copyright issue. Not making a moral argument here. My point, which I will repeat until I am stopped by force, is that whining about all the bad things that happen to PD materials (which you emphatically are NOT doing) has to, in my opinion, step up to the question of why our civic institutions don’t pay for digitization.

In addition to the cost of digitizing and developing metadata, there is the unknown cost of bandwidth. Many academic IT folks will argue against such initiatives without knowing the actual costs and without understanding the benefits that will accrue to the institution.

I’d like to point out, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) Publications Warehouse (pubs.usgs.gov) provides “access to over 130,000 publications written by USGS scientists over the century-plus history of the bureau.” All digital, all free, the website literally replaces a giant warehouse – hence the name! Digitizing this content was neither cheap nor easy, but USGS did it in the public interest.

While what NYPL has done in removing restrictions on public domain material is admirable, it is not particularly innovative among academic libraries. Cornell lifted its restrictions on the use of public domain material from the library in 2009; Yale subsequently lifted restrictions on reproductions of public domain items found in both its libraries and museums; and in 2014 Harvard also lifted restrictions on the reuse of most reproductions of public domain material found in its library collections. I am glad to see that NYPL has elected to follow the example of LC and some leading academic libraries.

Totally agree, Peter — there’s nothing particularly innovative about NYPL’s policy regarding public domain content. I present NYPL’s initiative here not as an example of innovation, but as a hortatory example to the many academic libraries that continue to impose artifical reuse restrictions on their public-domain holdings.

Thanks for posting this, Peter. Here’s more detail on the Harvard policy for those who want to follow up.

* the policy itself (September 30, 2014)

https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/programs/open-initiatives/hl-pd/

* the policy FAQ

https://osc.hul.harvard.edu/programs/open-initiatives/hl-pd/faq/

* the policy announcement

http://goo.gl/SRxvPx