Some years ago, I was one of the co-founders of the KBART initiative for metadata transfer. My interest in the project was sparked by a UKSG/Scholarly Information Strategies report on “Link resolvers and the serials supply chain”, which recommended the creation of best practice guidelines to improve the exchange of metadata between publishers and knowledge bases. I volunteered to convene a group to pursue this, thinking what was required was pretty straightforward and it would be all over by Christmas. Cue two years of detailed discussion just to get the first code of practice finalized (and several years of advocacy work and revisions since).

I remind myself of this story from time to time when I stray into thinking “really, how hard could it be to find a new, more equitable approach to scholarly communications”. Huge amounts of energy (= time + money) are being invested in exploring new approaches — from FORCE 11 and the Sydney Conference and OpenCon to the Open Scholarship Initiative (OSI) and the Scholarly Communication Institute (aka TriangleSCI), and that is barely scratching the surface. Note that I use the “scholarly communications” term but even that isn’t entirely agreed upon (People’s Front of Scholarly Communication vs Scholarly Communication People’s Front perhaps) — for some it is broadly interpreted to mean “making the outputs of scholarship available” (thereby encompassing both established mechanisms as well as emerging ones); for others it’s more about open access and indeed in some library job descriptions seems pretty much a synonym for “repository”.

Depending on definitions and scope, the conversations I’ve been involved in or read/heard about range widely: formats, stakeholders, workflows, business models, technology, values, skills, are all in the frame for consideration. It’s a great indication of the health of our community that nothing seems sacred, and that so many of us engage so enthusiastically in testing the status quo. The majority of such conversations seem to be initiated by universities, funders or indeed researchers themselves, rather than by publishers. Indeed, the extent to which (particularly “traditional”) publishers are welcomed varies; their presence is either interpreted as a positive commitment to rethinking how we meet overall goals of scholarship, or as a negative monitoring of the revolution until such time as the water cannon are required.

What troubles me is how much of the focus seems to be on conversation rather than action. On the one hand, I think it’s fantastic that UNESCO is funding 10 years’ worth of OSI discussions. On the other hand – TEN YEARS? How are we going to be communicating our research via holograms and brain implants by then if we’re still in talk mode? Having participated in (and been hugely inspired by) some of these groups myself, it is dispiriting that the ideas thus generated often get as far as a follow-up blog posting and no further. And it seems incohesive and uneconomical for Mellon, UNESCO and others to be separately funding very similar think tanks; what if we had fewer think tanks, and released more budget (not just that of the funders, but those of the sponsors, and the self-funding attendees) to support implementation of selected ideas?

I don’t doubt that there’s a little of the pre-KBART me talking here — impatient, naive, certain that change is easy to effect if you just put your back into it. But many of the interesting ideas that emerge from these discussion are not costly in terms of materials or systems, but costly in terms of time to research and test, to raise awareness and inspire change. Mapping and smoothing out the bumps in the road to consensus was what slowed down the KBART vision in those early days — but with our small group of knowledgeable people, committing regular time each month (and substantial quantities of it in the case of the co-chairs), we were able to make progress. In my continued work with UKSG in the years since, what’s clear is that people’s day jobs are now too pressured to enable them to take such an active role in community endeavors. We break the conference bubble, return to our day jobs, and have no capacity to take our discussion forward.

Of course, lack of capacity is not the only challenge. We’re not just trying to rebuild a plane while it’s in the air, we’re potentially trying to take one plane and convert it into a range of other aircraft that better suit the needs of their passengers. Hence I’m not suggesting that we should boil the entire future of scholarly communications down to one set of discussions — it’s clear that one size won’t fit all and we need the opportunity to tease out the nuances. But we need to be better at pooling the outputs from our discussion, and ensuring not only that future conversations build on what is gone before, but also that we shift the focus from conversation to action. This is where capacity is currently lacking and where I’d advocate for re-allocating some of the funding, budgets and sponsorship, to (in effect) a small secretariat for scholarly communications focused on synthesizing discussions and managing a framework for putting ideas into practice. I’ll bet that some answers already exist in the discussions we’ve had so far. To misquote William Gibson: The future’s here. It’s just not appropriately resourced.

Discussion

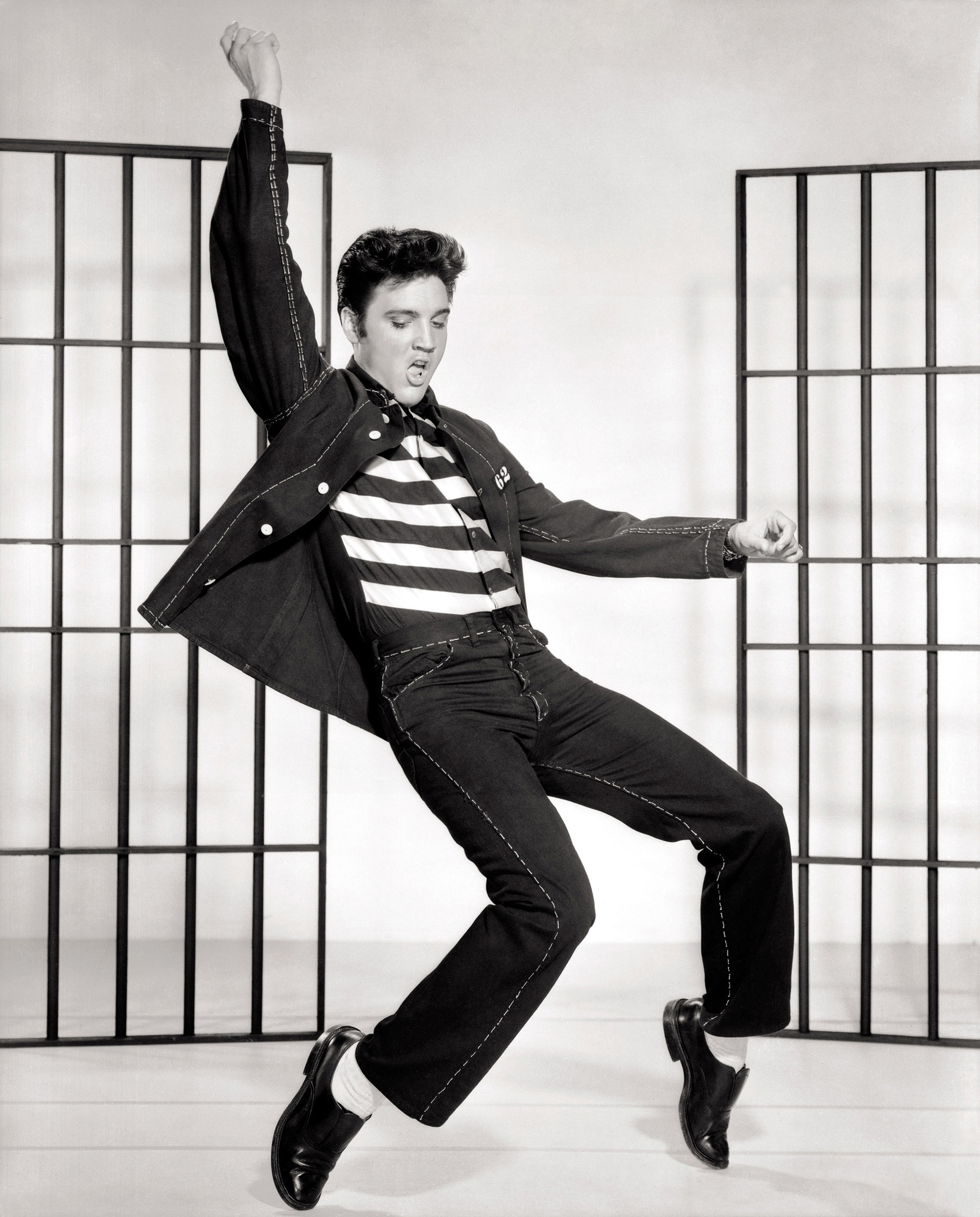

41 Thoughts on "Reinventing Scholarly Communications: A Little Less Conversation, A Little More Action?"

One notable example of a wide-ranging and lengthy study that seemingly had very little impact was the National Enquiry into Scholarly Communication, a three-year project (1976-1979) sponsored by the ACLS with funding from the NEH, Ford Foundation, Mellon Foundation, and Rockefeller Foundation that produced a final report of several hundred pages (published by The Johns Hopkins University Press in 1979) with many recommendations for change, some still very relevant today, almost none of which were acted upon.

I think a lot of the reason for all the talk and not much action is that publishers assume financial risks for authors and readers. Taking action requires financial risk-taking. I applaud many of the publishers (PLOS, Hindawi, BioMed Central, PeerJ, and others) who have taken financial risks in order to fulfill a vision of a new path forward, with generally good financial results. However, it also means these people go “all in” at some level, and don’t just sit on the sidelines and comment. They risk their day jobs. That takes sacrifice. Talking about change doesn’t require sacrifice. In fact, a lot of this seems to be a new way of using other people’s money — convincing or directing the industry to move in ways while taking no risks personally.

I don’t think resources are the issue. The future is here, the resources are available. Unfortunately, the future is not risk-free. But talking about it is.

I do half agree with you, Kent, but on the other hand I’m not sure about “other people’s money” – it’s all the same money, just moving through a cycle. At some points it’s funders’ or government money. At some points it’s universities’ money. At some points it’s publishers’ money – and yes, arguably publishers have shown themselves to be most likely to do something risky with that money. But isn’t that because there’s nowhere else that money *has* to go at that point? i.e. it’s not a case of “do we enable our patrons to access more content and services, or do we invest in innovation” for a publisher, as it would be for a library, say. Publishers are able to take risks because they have profits / surpluses that others don’t, and indeed if they are non-profit they MUST find something to do with their surpluses that benefits the community. Meanwhile in the case of start-up publishers, again, is it really their money they’re taking risks with? Maybe in the case of owner-directed companies (I guess Hindawi could be in that category, though I don’t know the details of their financing) but for PeerJ it was still funders’ money ultimately.

You’re so right, though, that the issue is as much about people’s willingness or ability to take risks, and that varies by which part of our community they’re in and how empowered they feel to experiment. I still think ultimately that we need more capacity to drive forward those experiments, wherever they take place!

In the university press world it has been the critical

role of the Mellon Foundation to fund initiatives involving risk so that presses can try new things without having to use their own funds. Project Muse, JSTOR, the ACLS Humanities and Guternberg-e projects, and many others have all been made possible by startup funding from Mellon.

On the other hand I am puzzled by the lack of discussion of big changes that are well underway. Examples include the US Public Access Program, CHORUS, SHARE (which is on the verge of becoming amazing) and the proliferation of hybrid and OA journals. It seems that people are too busy having visions to see the real changes. Revolutions are like that.

Today there are vast bodies of unstructured “data” or metadata on the Internet. Deep learning systems such as Google’s page view and Amazon’s are able to sense individual needs by a variety of techniques and to expediently refine. Others are in narrower fields with less powerful systems and create ontologies in, for example, biomedical research. All of this evolves with the idea to remove the need for humans to blend with these search strategies.

For the research arena, as long as these engines have access to the materials, metadata and the actual data itself, then Watson and off spring should be able, after suitable “learning” or training be able to meet an individual researcher’s interest regardless of where it is located. It may not be fully realized today, but, close.

One of the major issues is access where much of the data is restricted as in academic publishing. Hence the struggle seems to be to create metadata as a way to signal what is behind these walls as explicitly as possible. No barriers and an AI engine today is able to start to do context based research on full text or other files and make sense for a certain research need.

This is an inherent problem in how research is published and the “metadata” used, such as titles, key words, selective abstracts to “tease” a searcher to like a flower attracting a bee that this is “it”. With the rise of Watson and off-spring, even visual information can be searched and the systems can be trained, not only to detect needed information but to construct narrative.

It seems like KBART and even Kudos are based on publishers maintaining the current business models as to how they accept data and overlay metadata on top. From visiting the KBART site it seems that the struggle is with the limits of the human biocomputer and little foresight as to what is here or on the horizon in the AI field which is another challenge to the STEM/STM publishing community.

AI is certainly useful but nowhere near as powerful as you suggest. (AI hype is a constant.) Nor is it a challenge to publishers.

Hi Tom, this is an interesting hint at one of the developments that may bubble along relatively under the radar and then burst out one day and change everything, I guess! It’s not something I know so much about; as you point out, most efforts that happen now are still quite structured around our current system – it is possible to picture each such effort as a stone in the bridge to the future, but indeed there are many things that might just take off and fly us to the future instead of requiring us to build bridge and walk!

“Fewer think tanks, more budget.” Hear freaking hear. Of course, Kent’s point is well taken — there will always be a very high ratio of talking to action in the scholcomm space, because talking is low-cost and low-risk.

Talk, talk, and more talk. There certainly has been many groups talking and generous funding from any number of foundations but still after more than ten years the top 20 STM publishers that were supposed to change still receive 90% or more of their revenue from subscriptions sales to libraries. The prediction that the big deals were going away has never materialized, OA titles have been established in many scientific fields and libraries often still collect both the subscription title and the OA title. Authors are still flooding the top publishers with manuscripts for publication in subscription based journals. Impact factor is still king.

Report after report and recommendations often sit on the shelf with little implementation. The management level of many of the top 20 STM publishers are often never part of these discussions and yet everyone wonders why so little has changed.

Talk is cheap especially when someone else is paying for it. Changing is expensive and frankly why change when the cash cow is still giving plenty of milk.

I’d like to add that one of the major impediments to change is that our authors and readers don’t necessarily want much change. PDF, anyone?

“We” may want change, but why is that, if our supply-side and demand-side customers don’t? There may be an explanation in a great blog post (https://medium.com/@joshuatopolsky/your-media-business-will-not-be-saved-1b0716b5010c#.fl2leh8yf) on the topic of change in the media space:

“The truth is that the best and most important things the media . . . has ever made were not made to reach the most people — they were made to reach the right people. Because human beings exist, and we are not content consumption machines. What will save the media industry — or at least the part worth saving — is when we start making Real Things for people again, instead of programming for algorithms or New Things. . . . this industry . . . began to cede its power in the delivery and distribution process to other people. People who didn’t care about or understand the media business. People who told them the answer wasn’t the best of something, it was the most of something. Partially this was done out of fear, but mostly it was done out of ignorance.”

Do we want change because our customers want it? Or do we want change because it’s in someone else’s playbook that we change?

Meh. So what’s his argument here?—that having more content creators has meant more static and therefore it’s better to have fewer content creators? Or that readers are too dumb to know what they want so we shouldn’t give them choices? Or that the Internet hasn’t actually changed our expectations about what kind of information we want or expect? Or maybe that the world couldn’t possibly benefit from new ideas and new ways of doing things so we should stick with the old ones? Joshua makes some interesting observations in this article but I don’t quite see how they lead to his conclusion(s)….

I think his point is very clear — technology companies treat information as a quantity-based commodity (the more, the better), and have trained us to think that way because it suits their business purposes. It may not suit ours, or even be true for our audiences.

There is a relationship between problems with library budgets, reproducibility problems, and the quantity of articles being published now. If we published fewer articles, more geared to a population of readers and their needs and interests, we might see improvements on multiple fronts.

I doubt that the (evil?) technology companies have trained us (whoever us is). I do think that the problem with library budgets is that they have not kept up with the growth of research outputs, but that is not the research community’s fault, by any means. Should we restrict research to match the library budgets? Surely not. This is what makes APC Gold OA attractive, in that it makes publication part of the research budget, not the library budget.

To me reproducibility is a glaring red herring, one that ignores the scale of publication. Given two million articles a year, the fraction that requires reproduction is extremely small, almost zero. Restricting publication by say half, to just one million, would not improve reproducibility, but it would deny us a million new articles a year. Or are you proposing that half the world’s millions of researchers stop doing research, in order to reproduce the remaining researchers’ results?

In the immortal words of Montgomery Scott, “I’m givin’ it all she’s got captain!” The OSI2016 conference is just two months old and the workgroup papers and recommendations are available today—scoop! Go to http://journals.gmu.edu/osi. A summary of these ideas and proposals will be developed soon for broader audiences, and then we (the OSI planning group, which you and David are welcome to join, by the way) will begin figuring out which ideas to start pursuing right away (and following up on with OSI2017). There are a LOT of really innovative, energetic, amazing proposals in these papers that you wouldn’t expect to emerge from a diverse stakeholder conversation. But getting these off the ground, fine-tuned and widely adopted will take at least a couple of years—maybe not 10, but we won’t be done by Christmas. Fingers crossed. The next few months will tell whether and how fast we’ll be able to charge forward with action. And then maybe those holograms and brain implants can be on the agenda for OSI2025.

Ooh, thanks Glenn for the link / scoop! I will take a look. I maybe don’t know enough about how OSI is structured and what your plans are for taking action so sorry if I did you an injustice. Do feel free to elaborate here as I’m certainly interested in how you plan to take things forward, and I’m sure others who’ve read this post would be curious too!

Hi Charlie,

Sorry for the delayed reply. There are a number of steps moving in parallel right now, including planning the logistics for OSI2017, identifying new delegates, mapping the outreach strategy, fundraising, and fundamentally, trying to craft a broad agreement on how OSI should be structured and how this effort can be be most effective.In addition, we are currently distilling the OSI2016 papers into policy guidance—what kind of proposals are actionable now and later, what kinds of resources and commitments are needed, what are the missing pieces, how do we socialize these ideas and incorporate feedback, how do we leverage existing efforts and resources to accomplish these goals (assuming they’re worthwhile) and so on.

The most promising OSI2016 proposals and recommendations will become the major focal points of OSI2017, and OSI2017 delegates will continue to develop these more fully (plus new ideas as warranted). After some of these proposals are launched, future OSI workgroups will be tasked with reporting out to the full group on feedback, progress, roadblocks, refinements, and so on during subsequent conferences.

Finally, at a macro level, apart from the specific proposals that will be put forth for consideration by OSI workgroups, what can we tell about this effort from their past nine months of work? There’s broad support and enthusiasm for this effort among delegates, but it would be all too easy to discredit this by portraying the challenges ahead as insurmountable or the need for reform as nonexistent. Therefore, we’ll also be discussing and developing the big picture—continuing to build the case for a collective, collaborative effort so that even if the specific solutions developed at OSI2016 don’t gain wide acceptance, the idea of working together will gain more currency and the OSI effort will continue to learn, grow, and become more effective.

Best,

Glenn

Thanks, Glenn – I hope that your summary of OSI 2016, and the more actionable proposals within it, might be the catalyst to inspire some folks to take that action sooner rather than later. Perhaps OSI itself, in resourcing your post, will be able to ensure some of those actions happen more quickly.

Agreed. Back to your thesis, a little less talk, a little more action.

From the perspective of the Force11 Scholarly Commons Working Group (https://www.force11.org/group/scholarly-commons-working-group) I definitely recognize some of the barriers Charlie describes that are at play here, not least the limitations in time everyone involved is able to allocate to these initiatives.

At the same time, I think there is a lot of movement currently, not only in the amount of talk about reinventing scholarly communication, but, importantly, also in the amount of innovation we see happening, with new tools and services constantly being developed across the research workflow (e.g. see https://101innovations.wordpress.com/2015/12/25/timeline-of-tools). A lot of change is already happening, even if it is often still underused in the culture of assessment and review. Also at a policy level, there is action from many parties involved, exemplified by the concrete action of governments in Europe and the EU commission in shaping new Open Access and Open Science policies.

At Force11, we plan to take our current work on formulating principles for scholarly communication (https://www.force11.org/group/scholarly-commons-working-group/principles-scholarly-commons) further by mapping them against what is currently already available. Which current practices already conform to these principles, and where are gaps that should be addressed, for instance by improving infrastructure or influencing policy development?

This operationalization of principles, that will take place both online and in a workshop in San Diego in September of this year, will hopefully bridge the gap between talk and practice. We hope to end up with both a set of principles that stakeholders (including publishers) can stand behind, and actionable items to improve scholarly communication in practice.

Of course we cannot do this in a vacuum. We invite anyone interested to join us in the Scholarly Commons Working Group, and also hope for constructive dialogue and collaboration with the other groups and organizations looking at this very issue (in addition to the ones mentioned by Charlie already, for instance also the Working Group “Open Access and Scholarly Communication” of the Open Access Network Austria (OANA) that this week published the Vienna Principles: http://viennaprinciples.org/).

That there are multiple initiatives around this topic right now indicates that the need for change is broadly recognized. Personally, I see these multiple initiatives not as duplication of effort, but as necessary plurality in the development of ideas in a time of change. Centralizing these efforts too soon will limit the scope and breadth of these discussions, as well as the number of people that choose to be involved in them.

Thanks, Bianca, for sharing the next steps in the process for the Force 11 scholarly commons process, and I think your point about plurality in the development of ideas is well made! I guess my concern is not so much that there are lots of conversations, but that the ratio of conversation to action is too much skewed towards conversation. But I can see that with so many useful conversations taking place, and proceeding at different paces, it is hard to know at what point it would be useful to add more capacity to help bring the resulting ideas to life – or what model would work to provide funding for that to happen. That’s another conversation in itself!

The reason I love OpenCon is because it is organised to lead to action: see my take on OpenCon: https://pkp.sfu.ca/2016/06/16/opencon2016/

Thanks for the link, Juan Pablo – great to see the focus on RPT because I’d agree with you that’s the nub of the problem and change there will make it much easier for change to happen elsewhere. Have you written up any more details about the project or is it still at the info-gathering stage? Exciting stuff.

After a bit of digging I discovered that RTP stands for review, promotion, and tenure. If that is the nub of the problem, what is the problem? I do not yet see a problem. Nor for that matter do I see the scholarly communication community reinventing RTP, which it has almost nothing to do with. RTP is done collectively by faculty and administration. Perhaps there is some overreaching going on here.

Hi David – the problem I think a lot of us see is that RTP (apologies for that acronym!) processes often include publication as part of the evaluation. That requirement is arguably propping up traditional systems (from business models to review models to rankings), and thereby hampering innovation because the “market” is not free to choose new models. It may not be the role of the scholarly communication community to change this – but (a) many of us care about innovation, whether to make better use of technology, or to make scholarship more open, or for other reasons and (b) publishers are roundly criticized for failing to support new initiatives – if they feel their endeavors are constrained by current RTP processes, then it does seem logical to try and address that.

Of course evaluation includes publication, how could it not? Publication and funding are the primary measures of success, which makes sense. The only problem I see is that people think the way the world is, is somehow wrong. In my view they are wrong, which makes this a big problem indeed. Innovation should not depend on demonizing present practice.

However, the RTP players often make the false assumption that decisions publishers make can be construed as judgments about quality pure and simple, but as the AAUP and others have pointed out many times, decisions about what to publish involve much more than decisions about quality–market projections, fit for the list, etc. Tjherefore, it is far too simple to regard a publishing decisions as a stand-in for the judgment about quality that RTP should be focusing on.

I seriously doubt that RTP decisions are as simple as this common refrain makes them out to be, especially tenure. Given the nature of the decisions and the people making them I expect the process is quite complex. But various aspects of publication are and should be major pieces of evidence. Is there any research on RTP decision making?

No research yet that I’m aware of – but that seems to be what Juan Pablo (and Meredith Niles and Erin McKiernan) will be doing – and of course they may be aware of any existing research in this area (if still reading!)

Google Scholar returns 364,000 hits for an (all dates, full text) search on promotion + tenure. Many of the first ranked are of a how-to nature. GS also suggests having all four words — promotion tenure publication quality — as a related search and gives 215,000 items in return. These large numbers suggest we are picking up a lot of extraneous material. I would expect hundreds or thousands, not hundreds of thousands. But there still looks to be a lot of extant research on this topic.

I know of no systematic studies of how the RTP process uses publication as a metric in decisions about P&T, but I have heard many accounts from scholars who went through it that often great weight is given to the “prestige” of the publisher or of the journal independent of any assessment of the merits of a publication undertaken by members of the P&T committee on their own (who are sometimes presented with so much material that they don’t bother to read it all but simply reply instead on the “prestige of publisher or journal” metric. This reliance seems to assume that the publisher’s decision is based mostly on merit than on other considerations, like sales potential for books. But as we in publishing all know, there is no direct correlation between scholarly merit and commercial success. P&T committees seem to conveniently ignore this fact.

Turns out there is a lot of research. Here is a place to start browsing:

http://scholar.google.com/scholar?as_q=promotion+tenure+publication+quality&as_epq=&as_oq=&as_eq=&as_occt=any&as_sauthors=&as_publication=&as_ylo=2015&as_yhi=2015&btnG=&hl=en&as_sdt=0%2C49

The prestige of the journal is an important piece of information, as are citations. Nor are evaluators likely to be experts on a candidate’s research so cannot judge their papers. That sort of evidence probably comes from Department heads, letters of support, etc. It is a complex reasoning process. I am sure no one bases RPT decisions simply on journal weight, but that weight is important evidence, not to be ignored.

No doubt there is a more straightforward correlation between quality and journal prestige than there is with books because decisions about accepting articles do not have to factor in other considerations like market potential.

David – it’s not so much that people think the way the world is is _wrong_ – it’s that people consider there are improvements that could be made (e.g. better accessibility of research, whether in the sense of delivery formats or business models). I agree that it’s not helpful to demonize present practice but I think it is important that we recognize where it doesn’t serve us as well as it could! Sandy’s point is well-made here: publishing models weren’t designed with RTP evaluation as their primary use case. What if we could find a better way to do RTP evaluation, and thus “liberate” publishing from that responsibility, enabling it to serve other purposes better?

Wanting the scholarly community to cease using publication for the purpose of peer evaluation is certainly wanting the world to be fundamentally different from the way it actually is. You can provide additional forms of evidence, altmetrics for instance. But we cannot rule out important evidence, which publication provides.

Moreover, the journal system as a whole does rank research results by importance. That is a central aspect of peer review and especially rejection. If we want to stop being useful for RTP then simply publish everything that is submitted. This is the magnitude of the change people are calling for. In my view it is unrealistic, hence a problem by itself.

Question/observation: Architects have built “campuses” without putting in sidewalks, waiting to see how traffic identifies movement of individuals. Shaping Tomorrow, Shapingtomorrow.com is a foresight database, knowledge extraction and analysis site that crosses all disciplinary areas, many not in scholarly journals. ST let’s users submit sites of relevance to their own interests and the system then starts to build a database of ontologies developed by users, open access. It does not attempt to anticipate the ontological database.

Thus, the pain expressed in the discussions here and summary of past efforts in various working groups seems to be minimized as such ontologies wax and wane based on past, present and future needs of those using the database regardless of attempts to classify and anticipate

For STEM/STM journals, it does seem dependent on open access which may be one of the unspoken barriers around which these efforts are dancing. Siince the best development needs to get to full text and not just metadata such as titles, keywords and abstracts.

thoughts?

Ontologies are not all that useful and algorithmically generated ontologies may not be useful at all, especially when it comes to issue analysis. Beyond that, the concept of a “foresight database” is hyperbolic at best. Full text is certainly useful as a discovery tool, which is why Google Scholar uses it. (My understanding is that Scopus only uses abstracts, which are a tiny fraction of full text.) I myself have developed a full text algorithm that maps local scientific neighborhoods.

But you seem not to be talking about search or discovery. It is unclear to me just what you are talking about, especially when you refer to “the pain expressed in the discussions here and summary of past efforts in various working groups…” Innovation is painful and no ontology can change that.

My concern is that terms like “reinventing” scholarly communication is becoming an empty mantra, like “reform” has become in education. I just did a Goggle Scholar search on the Boolean union of the terms “education” and “reform,” and got about 2.6 million hits. That is astronomical. For the scholarly literature for 2015 alone I got about 86,000 items, mostly journal articles and books. Clearly the term reform has lost its meaning in education. The same may well be happening with the lexicon of change in scholarly communication. In particular, experimentation is not change. This distinction seems already to have been lost.