My last post was about institutional conservatism in relation to research evaluation and reward. I illustrated it with a brick wall bearing the words “insert head here” because so many wicked problems in scholarly communications today can be traced back to this underlying cause, and its immutability is therefore so frustrating to those trying to tackle its symptoms.

One of the many symptoms is that publishers and researchers are inextricably linked, mutually dependent, and likely to remain so for the foreseeable future. Evaluation processes — even those that are evolving away from simplistic publication counts or Impact Factor-based points systems — still mean that publication in an established journal is important for researchers, much as quality submissions are important for publishers. It is into this stasis that “scholarly collaboration networks” (SCNs) have emerged, originally as places for researchers to form connections (à la LinkedIn) but increasingly used for “content swapping” and / or “quasi-legal downloading of research papers”.

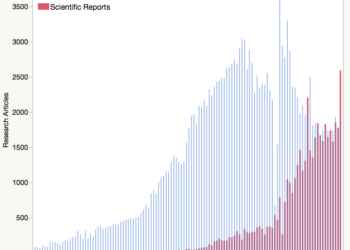

Quite what SCNs are used for, and by whom, and what threats / opportunities they represent, has been a topic of conversation both on and off the agenda at pretty much every meeting I’ve attended recently. It is a commonly held belief that SCNs have become more focused on content sharing than on other kinds of collaboration between researchers, but evidence to support this assertion has been limited. José Luis Ortega’s interpretation of over 1 million records from scholarly collaboration networks was that SCNs are being used not, primarily, for collaboration, but for posting and accessing work; however, the most recent large scale survey, Nature’s 2014 study of “online collaboration: scientists and the social network”, showed only 35% of ResearchGate users (for example) selecting “post content” as one of the activities carried out on the site, with 33% using it to discover content — whereas 68% were on the site for a much more passive purpose, “in case contacted”.

In this context, I’ve recently worked with a group of publishers to carry out a new survey to update our understanding of how and why researchers are using SCNs, and shape next steps in terms of how publishers might best engage. The survey had over 7,500 respondents from around the world, all career levels, and all subject areas, though the bias is towards STEM (64% over 36% HSS), developed countries (40% Europe, 18% North America) and early career (39% within 1-10 years of completing PhD). Headline findings are that 57% of respondents indicated that they upload copies of their work to SCNs and 66% access work in this way. Of course, the survey respondents are not the same as those who participated in Nature’s study 3 years ago, and direct comparisons can’t be drawn, but one way or another, that looks like quite a shift in just 3 years. (It might also, of course, be a shift in researchers’ overall consciousness of sharing, and in their willingness to be open about this behavior — although our survey was sponsored by publishers, the survey was carried out by a third party, responses were anonymous, and publishers did not have access to the raw data, meaning that responses could not be tracked back to individuals; I don’t know the relevant specifics in relation to the Nature survey, but should acknowledge the possibility that respondents there may have underreported their use of SCNs to share and access work — thanks to Nicko Goncharoff for musing on this point).

Headline findings are that 57% of respondents indicated that they upload copies of their work to SCNs and 66% access work in this way.

Digging into respondents’ views around copyright provided further useful insight. Firstly, the assumption that people share via SCNs primarily for convenience (rather than because of specific intent to undermine traditional publishing models) may be given some substance by the finding that 83% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that copyright should be respected. The attitudes to copyright suggested by the survey may be surprising: on balance, respondents considered publisher copyright / sharing policies to be: “straightforward” (48%, vs 34% “confusing”), “fair” (39%, vs 27% “not fair”) and fit for purpose (44%, vs 23% saying policies “do not serve their purpose adequately”). On the other hand, 42% considered copyright to be “restrictive” (vs 34% “permissive”), and despite the strong sense that copyright should be respected, 60% felt they should nonetheless be able to upload work to SCNs. 21% didn’t realize that copyright / sharing policies might apply when sharing their work, and 82% thought it would be useful to have a single place to check policies — good news for the STM-led “How Can I Share It” initiative).

What does any of this mean for Scholarly Kitchen readers? Usage of SCNs is (probably) growing, and (probably) changing, with authors more actively using SCNs to access and upload work in a dissemination ecosystem completely separate to that provided by publishers and libraries. SCNs have become a major discovery channel, maximizing visibility of research (good thing), albeit in a way that is largely uncounted by publishers, institutions and funders (bad thing, for authors too, as it further complicates their ability to get an overall sense of the readership of their work). As a publisher, if you haven’t already done so, it’s worth auditing the extent to which your content is available, and within that, the level of copyright compliance (Hamid Jamali’s recent study found that 51.3% of 392 non-OA full text articles in ResearchGate were non-compliant with publishers’ policy). This should help prioritise and focus how you respond: from educating authors about copyright and metrics, to working with them to identify and support approaches to sharing that harness the visibility provided by SCNs, without undermining the publishing processes and metrics so necessary under current institutional reward mechanisms.

Discussion

12 Thoughts on "Updated Figures on the Scale and Nature of Researchers’ Use of Scholarly Collaboration Networks"

In the final paragraph, “as a publisher, if you haven’t already done so, it’s worth auditing the extent to which your content is available, and within that, the level of copyright compliance…”

A comprehensive audit would be a challenge, and would seem to require cooperation from ResearchGate (RG). Hamid Jamali’s recent study describes an involved process where he download 437 with ResearchGate’s XML site maps with 50,000 records each, and then randomly selected 500 records, read each one, and then tracked them back to the publisher’s website to see if they were in compliance. This was March 2015, but he notes that subsequently RG no longer allows access to these XML site maps. Without RG’s cooperation, it would seem to take a tedious manual effort to sort through more than a small sample. I was further astounded that only 51% of Jamali’s non-OA sample were non-compliant with publisher’s policies. I’ve never tracked it, but I download several articles a week from RG and I seldom see anything other than the publisher’s PDF version of record. Makes me wonder why bother to post author versions if few others do, but apparently a large minority do so.

Another RG curiosity is who or what is doing the full text downloads. Sometimes while my articles are in the 1-year timeout, I’ll upload a “full text” placeholder that prominently says that the article is still within embargo, but here’s my email and give me a click and I’ll be happy to send it. These faux full text placeholders get downloaded hundreds of times but I seldom get email requests that appear to come via RG as opposed to requests from the publisher’s site.

I was also surprised to read that more of Charlie’s survey respondents considered publisher copyright / sharing policies to be straightforward than confusing. RG links to the Sherpa RoMEO site for authors’ to check policies. The Sherpa RoMEO definition of Green OA, the version allowed by most STM publishers is that authors “can archive pre-print and post-print or publisher’s version/PDF.” Huh? It makes it sound a lot more liberal than the actual copyright transfer agreements I’ve recently received from “OA Green” listed publishers.

Hi Chris, yes, I’d agree, a comprehensive audit is probably not realistic but at the very least doing some spotchecking around e.g. a 2015 issue of each journal might be a starting point for assessing the scale of sharing for a specific publisher / journal.

Very interested to hear about your placeholders being downloaded, but very few requests arising from these. Thanks too for sharing your experiences of Sherpa RoMEO. We can hope that the continued efforts of “How Can I Share It” might see simplification; part of the job to be done here is educating editors and ed boards to see the value of achieving greater simplicity and consistency across journals!

Hi Charlie,

I think, you nail the issue on the head, when you talk about convenience for the researcher, as, indeed, SCNs have become a major discovery channel, which is also maximising visibility of their own research.

Your study should give food for thought for publishers to develop more researcher-centric services!

Sabine

Thanks, Sabine!

Hi Charlie,

Thanks for a good post, very relevant when RG seems to be getting increasingly popular among researchers. Even though many are still probably confused on what constitutes a copyright violation when uploading work to SCNs, I feel RG has become a useful channel for discovery as you mentioned. What I didn’t entirely understand was your view on RG complicating researchers’ overall sense of the readership of their work. I would argue otherwise. I feel the site gives simple but valuable information on which parts of the world your readership comes from. Similar tools are of course available at Mendeley, which is still however way weaker as an SCN. Could see a lot more value created on this front by traditional publishers.

Hi Mikko, thanks for your comment! My thinking around understanding the readership of a work is that copies on SCNs create (further) fragmentation of usage statistics, and while publishers / institutions (say) could work together to provide consolidated counts across publisher / repository versions, the “walled garden” nature of SCNs means that the onus is on the author themself to add that usage into the picture – and in whatever context / to whatever extent usage counts are used, it’s possible therefore that a potentially significant level of usage, via SCNs, is not being included. For the author to address this creates a new layer of complexity – that’s what I was getting at! I agree with you that RG does on the face of it provide good metrics / detail to authors. For me it’s just a question of how to join that up with the “bigger picture” to give an author as strong as possible an understanding of their work.

Hi Charlie,

It is a good contribution however, different part of the other scholarly network, academia.edu, menedely, selected works etc. I found also violation of copyright by the author in these Academic Scholarly Networking Site (ASNS). Point to ponder how can we control it uploading of fulltext article.

However, it is interesting at international level we should designed the author Al-metrics site where we can judge the credibility of author works. KUDOS is one of the good platform to promote your research.

The interest seems to be on the posted articles separate from the scholarly journal associated with the article. This seems to say that readers (and therefore contributors) are more interested either in the particular author or the subject matter of the article rather than how it is bound within the published journals.

Of course this also plays into how authors position what they write and, particularly, references cited in order to raise the possibilities for others to access the materials which also has been of interest when publishers try to drive readers and downloads from their sites.

The increased sophistication of search engines to scan through titles, abstracts and text mine also makes such specific search/recover materials easier and encouraging the SCN’s. The idea of adding “comments” by publishers seems a futile attempt to respond to activities such as SCN’s. Couple this with the rise of OA of various colors points to change, albeit slow. Like the frog sitting in the water heating on the stove, this may be a cautionary note.