Evolving forms of digital scholarship such a 3-D images, multimedia, and geographic data are relatively new elements in the scholar’s workflow. These formats appear in stark contrast to the legacy books and journal articles required for career advancement within the academy. How do these tools fit into the current landscape and what are the implications for publishers?

Two scholars recently shed light on this topic as they shared their research as part of a Regional Program planned by Society for Scholarly Publishing (SSP) members in Philadelphia. Jen Grayburn, Council on Library and Information Resources (CLIR) Postdoctoral Fellow at Temple University and Kathi Martin, Professor and Associate Director of Graduate Fashion Design at Drexel University discussed the potential and challenges of working with developing and image based technologies. Their talks were complemented by Alex Humphreys’ experiences with innovative services as Director of JSTOR Labs. As part of the organizing team of publishers, librarians, and consultants, I found this session fascinating and we believed that it would be of interest to a much broader audience – hence this post.

Use of 3D tools highlights need for best practices

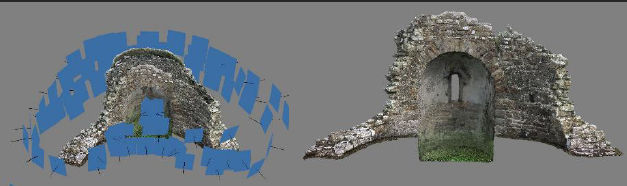

Jen’s research combines text mining, 3D visualization technologies and Geographic Information Software (GIS) in a forensic examination of the relocation of a historic church in Scotland. The insights gained from an elevated view of the site in 3D, highlighted aspects of the landscape that prompted her to consider how changes in international sea routes in the 12th century influenced the decision to move the church.

In responding to our questions about publishing the results of her research, Jen noted that a key difference between writing a book and working on a digital project is determining when/if the project is done. When a traditional publication is disseminated and preserved, it often indicates the successful completion of research. However, 3D data files provide the flexibility to reevaluate, alter and test more data even after it is released.

Furthermore, different methods of preservation enable different capabilities, for example, proprietary PhotoScan filesvs geometry files vs 3D PDF files. Currently there isn’t a standard infrastructure to preserve and support 3D data. Experts in the discipline may be able to evaluate the research but not necessarily the digital methods and components. Given these challenges academic departments have been slow to reward digital projects or have a process for incorporating them in formal evaluations.

Given these limitations, she is enthusiastic about two grants from the Institute of Museum and Library Services (IMLS) and the CLIR to gather scholars from different disciplines to develop a common understanding of these problems. There are two projects: Community Standards for 3D Data Preservation (CS3DP) and 3D/VR Creation and Curation in Higher Education.

How Best Practices Extend the Value of a Collection

Kathi Martin works at the intersection of fashion and information science at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Under Kathi’s direction, the Drexel Digital Museum Project (DDM) has provided online access to its own collection as well as holdings of private collections. Typically in historic exhibits, distance from the objects and low lighting can obscure design elements. High resolution images improve viewing by providing close-ups of the construction and embellishments that are important to students in learning their craft. By providing greater visibility of these collections through online images, Drexel has served the needs of research and education, and gained additional funding to hire a curator and several staff.

The DDM employs best practices in image capture, information architecture and metadata harvesting which served them well when Quicktime VR died as they were able to re-purpose the images as plugin free MP4. Now they are researching best practices for 3D Object Virtual Reality (Object VR) which can be re-purposed as web ready HTML5. This approach provides them a smooth path forward.

High resolution image files range 350 gigabytes in size and are accompanied by rich metadata descriptions using Metadata Object Description Schema (MODS) and Persistent Uniform Resource Locators (PURLS) that ensure continued discovery, access and conservation. Drexel staff are part of an international effort to create an open shared vocabulary and visual thesaurus for fashion. Descriptive metadata using a specific structure that supports Linked Open Data supports the broadest possible use by remote users anytime, anywhere.

A key difference between writing a book and working on a digital project is determining when/if the project is done.

For example, one of the gowns on exhibit was worn by Princess Grace of Monaco, a former native of Philadelphia, when the city celebrated her 50th birthday. Digital assets include images of her wearing the gown, press images, user generated content of the exhibition, along with video footage for additional context. Together these provide a more complete user experience of the garment and the wearer in a different era. Using technology to engage the user in viewing the artifact gives them the ability to customize their encounter with each object ultimately extending the narrative of the original garment through digital means.

In the stories Jen and Kathi shared they describe how they use tools to generate content in the form of data and images. JSTOR Labs works with content to create tools that enhance the user’s experience.

Tools Designed to Enhance the Use of Content

Alex Humphreys is the Director of JSTOR Labs which was created three years ago with one goal:

To shape the future of research and teaching, one project at a time. Working with partner publishers, libraries and labs, we aim to create tools for researchers, teachers and students that are immediately useful – and a little bit magical.

Alex describes the team’s projects as being informed by the work of digital scholars like Jen and Kathi. JSTOR Labs adopts some of the same digital technologies, and it engages similarly in exploratory projects. Alex emphasized the importance of “play” to these explorations, describing the partnerships that work on these projects as “playdates.” Throughout the development, hypotheses and designs are refined through multiple iterations based on user feedback as the tools are created. The following examples are tools that expand the use of the content by providing a fresh approach to accessing it.

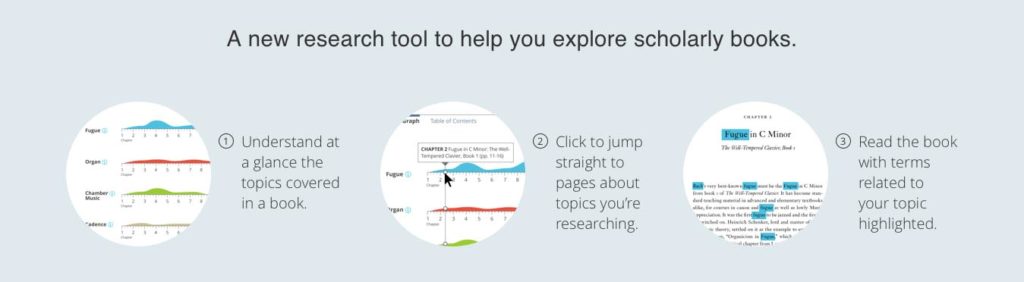

- Seeking to Reimagine the Monograph, the key question was how to improve the experience and value of longform scholarship. One possible solution is the creation of a topicgraph that provides a fingerprint of a monograph. Each term has a set of associated keywords that enable the reader to more easily explore the content, go directly to the most relevant pages with terms and to read the content with the terms highlighted.

- Through a partnership with the Folger Shakespeare Library, the Understanding Shakespeare tool enables the reader to find a line in a play and link to a list of articles in JSTOR that contain that line.

- Text Analyzer digests a text submitted by the reader and returns articles and chapters from JSTOR that are about the same topics. This is popular both with junior researchers learning how to conduct an academic search and with students writing a dissertation to uncover citations important to their work. Alex demoed an experimental extension of Text Analyzer that allows a user to submit a text in one language to find related articles and books in their preferred language.

These tools advance scholarship by enhancing the utility of content and the value of it.

Development and sustainability of tools

A question at the close of the session raised the matter of sustainability of tools. While the preferred view is open access content and open source tools, there can be ongoing development costs. Some felt that the capabilities being developed had the potential for commercial applications that could be done in a responsible manner.

What is your experience with digital scholarship? Are there instances where innovative and creative approaches were accepted as part of the evaluation process? What has to change for the academy to accept something other than a traditional publication as a demonstration of expertise?

I’d like to extend thanks to the three speakers as well as members of the SSP Planning Team, especially Emma Sanders whose notes were helpful in writing this post.

Discussion

2 Thoughts on "Innovative Research and Creative Output: From Ideas to Impact"

Writing a book or journal article does not mean the project is done! It means that what is believed to be known at the moment is being presented for others to appreciate. As for the research it goes on. The same can be said for producing something on a computer. The difference between using the computer and using print is that print is not reliant on changing technology. To think we use to use tubes, then transistors and now integrated circuits. Ever try to download a compact disc?

In days of yore one had a very detailed index and indeed the index could and often did hold its own copyright. If one looks back and reviews the Syntopicon one is looking at a text analyzer that covers a vast number of books.

I am all for innovative methods to present material and discover what is in it, but the goal of any presentation method, I would hope, is to make the material easily creatable and accessible.

The humanities which sees bound volumes as evidence of scholarly publishing may have the edge both with respect to non-standard print media and the acceptance of longer periods between “publications” which addresses the issue here of when the work is “complete”.

Science seems to be driven by “speed” and the acceptance of work that has been published while the research is “in progress”. There are a plethora of reasons for this but both the academics and their institutions as well as the editors and their respective journals seem to reinforce this pattern which is a challenge when the ideas presented here become standard practice. Many of the reasons in STEM areas such as proprietary revelations can be critical but for a large percentage of the literature, it is persiflage and designed to meet other needs.