Last week, Public Library of Science (PLOS) CEO (and Scholarly Kitchen Chef) Alison Mudditt released an open letter to the community in which she outlined the organization’s priorities going forward. Included in the letter was a note that development on PLOS’ ambitious workflow system, Aperta, was being shut down. While disappointing to many in the community who had high hopes for much-needed improvements in the manuscript submission process, this serves as yet another reminder of the complexity involved in building such systems.

Back in 2013, Joe Esposito wrote about the one universal point of agreement among all researchers:

What do almost all scientists agree about? The manuscript management systems employed by most publishers. Scientists detest these systems. They find them to be cumbersome and they express real frustration and sometimes outright anger over them. I will forebear naming names here, but some of the most prominent publishers and vendors of workflow management systems come under fire.

Having spent the last few weeks meeting with journal editorial boards, I can attest that editors aren’t too keen on most of the current offerings either. On both sides of the process, the systems in use seem needlessly complex and hard to maintain, with powerful capabilities often hidden from the user. One assumes that these systems, like most other commonly-used software, have accumulated a great deal of cruft over the years. So it would seem to make sense to start from scratch and build a new, modern manuscript submission system from the ground up.

But clearly that task is a lot harder than one would think. From the outside it seems a straightforward activity, but as Cameron Neylon explained back in 2015, this is an area where scale becomes a major problem, rather than an advantage:

If documents came into this process in a standardised form it would be easy. But they don’t. And they don’t on a large scale. One of the key elements we will see over and over again in this series is that scholarly publishing often doesn’t achieve economics of scale because its inputs are messy and heterogeneous. Depending on the level of finish that a publisher wants to provide, the level of cleanup required can differ drastically. Often any specific problem is a matter of a few minutes work, but every fix is subtly different…

…The few examples of systems that users actually like are purpose built by small publishers. Many people have said it should be easy to build a submission system. And its true. It is easy to build a system to manage one specific work flow and one specific journal, particularly a small one. But building something that is flexible(ish) and works reliably at a scale of tens or hundreds of thousands of articles is quite a different issue.

Neylon gets to the heart of the problem faced when building a submission system, namely the complexity with which they have to deal. From what I’ve heard, even the smaller bespoke submission systems he talks about require a significant amount of manual intervention, something that’s a complete non-starter for a large journal or set of journals.

In the intervening years since the post was published, the complexity of the material coming in to journals has only continued to increase as articles increasingly contain new types of media and new types of content (think data, or code for example). But perhaps even more than the variation in incoming documents, the great variability in editorial processes within and across journals is a major confounding factor.

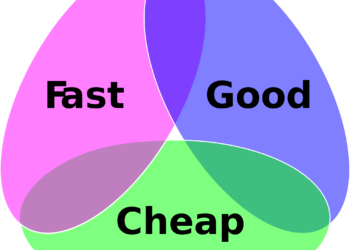

In speaking with Allison about Aperta, the initial work involved modernizing and simplifying the user interface for authors, and she sees this a success. Where they ran into trouble was in working with editorial teams using the system. Each editorial office has its own personality, its own go-to features and its own “can’t live without” functionality. Peer review standards and processes vary from journal to journal. This makes it very difficult to build a system around a standardized workflow because there is no agreement among journals as to what that should be. Trying to accommodate even a limited number of editorial offices turned Aperta’s planned lightweight system into something heavy and cumbersome, much like the products already on the market.

There are no easy answers here. The editorial practices and workflows are important differentiators between titles. Standardizing all journals on one homogenous system would remove variation and choice from the market.

As Neylon notes, Elsevier has spent years and reportedly tens of millions of dollars trying to build a better submission system, and still runs a variant of Aries’ Editorial Manager. Thus, it’s perhaps not surprising that PLOS hit the same roadblocks that have plagued other attempts. Making these sorts of bold gambles has been a strength for PLOS, and not every gamble will fully pay off. On the positive side, the improvements in Aperta’s user interface offer value, and as Mudditt notes, “we’ve had great feedback on the interface from users and hope to be able to repurpose that experience in the future.”

So if not the planned revolution, at least there’s hope for some evolution to ease a major pain point for scholarly authors and it’s worth keeping an eye on how PLOS puts into practice those lessons learned.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "The End of Aperta: Journal Submission Systems Remain Challenging"

Interesting article. There is no question that most publishers while good at many tasks just don’t have the talent in-house to take on significant software development projects. Article submission, online hosting services, and fulfillment systems are all best left to specialized companies that design and build systems for publishers. Once in a while a publisher will believe that they have the talent to take on a project only to abandon that effort after spending far too much money with little results. Even the mighty Elsevier has been humbled in their attempts to build a manuscript submission and tracking system.

If fact, it has been my experience even when publishers buy an outside system, they have trouble implementing it or maintaining the updates or new releases. In my consulting business I have often found examples of plans to move to new hosting service or a new fulfillment systems where the implementation took twice as long as required or more to implement and even then only partial implementation was achieved.

Too often publishers have a limited view of technology or are not willing to invest the resources to achieve even a minimum level of competence in this area.

Given the commitment to technology that publishers now are making, I think buying outside systems is going to continue for many years to come. Thank goodness that Alison was able to take this decision. Too often management supports these development projects long after a change in director is required.

Actually, Elsevier did build a new system from the ground up, called EVISE (www.elsevier.com/editors/evise), which was rolled out in 2016/2017.

I have a journal that uses EVISE. We were one of the very early adopters and I regret agreeing every day I interact with it. What drew me into the platform was the promise from Elsevier that it would be leaner (great if much of the workflow happens in low bandwidth settings such as Africa) and more editable to fit different journal workflows (receiving mainly papers from non-English first language authors, we have an author assist step in the pre-peer review workflow for some papers, as well as an in-house copy-editing step prior to production). It wasn’t either and none of our preferences could be met. Our view is that we were left with less freedom than we had on EES. Interestingly very few (if any) of the flagship journals in my specialty adopted EVISE. I know of one journal that went on EVISE and then changed back to EES after a few months. I guess the tricky issue as the author stated is addressing the unique workflows of different journals. I used to think we were the only journal with these issues, but am encouraged to see that this is not the case. Perhaps publishers will take note at some point?

The Guardian had an article on the rise of Robert Maxwell’s empire in scientific publishing:

http://tinyurl.com/ycjxmzuq

Basically, as you note, few systems deal effectively with the high cost of editing, particularly for articles that come from non-English speaking authors and from those who follow form but not substance in order to meet demands for publishing, often turning in a fully formed paper around a single or a few data points.

The question is: For whom is the “workflow” system?” For most, it seems like it seems to be for authors and editors (the collegial part of academic publishing). In reality, in the past, and still current, mostly, its for the publishers (note the discussion here refers to publishers with many and varied journals) and their administrative overhead including actual production, collection of requirements such as copyrights, process for acceptance and revisions, and the compulsion of a uniformity across individual and the collection of journals, basically marketing demands. In reality, it’s the authors and editors who need to fit into the workflow needs of the publisher from submission to creation of a marketable product once launched into the world.

As the previous articles on predatory journals and the two on workflow issues (and follow-on comments) indicate, we may be seeing, in part, the barriers to entrance of both small journals and those who want a public voice for their research and which may need to be challenged.

The articles on workflow development point to the two elephants in the publishing industry and clearly sounds an alarm to the smaller houses still included in the community of legitimate academic journals. A recent webinar aimed at the single or small family of journals on how to “look like” the ranked journals makes very clear what the rules on the pitch are. Journal submission systems are part of this Labyrinth to navigate and which may become moot in the age of increasing intelligent systems. These may be curing problems of the past

David, thank you for this piece, especially for introducing me to the word cruft. If PLOS can’t start with a blank piece of paper and succeed with implementing a new submission and peer review workflow, it doesn’t bode well for the rest of the industry. As far as I know, PLOS has never gone to print, never had to deliver it’s content to the institutional market, and doesn’t do society publishing (where editorial practices are harder to standardize.) While I think this is a wise move for PLOS, who can make better bets to achieve publishing scale and impact than developing and supporting a proprietary editorial system, I hope it doesn’t encourage publishers and vendors in this space to recede into complacency. We are an industry where workflow is often a matter of form and rooted in tradition. When the biorXivs of the world start seriously taking on the challenge of classifying, verifying and sorting science for its interestingness, I doubt they will encumber themselves with the stately traditions of academic publishing.