I’m on the record as having suggested that institutional, funder-imposed, and governmental open access (OA) mandates have troubling implications for academic freedom, given that academic freedom includes — according to the statement promulgated by the American Association of University Professors — “full freedom… in publication.”* You can’t simultaneously enjoy “full freedom in publication” and operate under a regime that requires you to publish in very specific ways — especially when those modes of publication require you to give up important rights granted to you by law.

When I’ve raised these concerns in the past, I’ve often been asked (usually by people who are strongly in favor of institutional, funder-based, and/or governmental OA mandates) whether I have the same concerns about a journal’s or publisher’s requirement that authors relinquish copyright in return for the their publishing services. After all, in both cases the author is being asked to relinquish control over her work in return for something else she wants. Aren’t journal publishers being just as coercive when they require copyright transfer as funders are when they require OA publication with a CC BY license? This question has usually come in relatively constraining forums like Twitter and online commenting threads, where it can be tough to respond effectively to a question this complex. Hence this posting, in which I’ll try to explain my thinking on this issue, which I think is a very important one.

The first crucial thing to bear in mind is that when dealing with questions of freedom and coercion generally, we are not dealing with a binary issue. There’s no scenario available to faculty authors that offers either perfect freedom or absolute constraint. Even at their most free, academic authors are still generally expected by their peers to publish in quality scholarly journals, and their careers are hobbled when they fail to do so; even under the most constraining scenarios, authors usually still have some degree of choice between publishing venues (although some emerging models, like Plan S, would have particularly severe effects on authors’ freedom to choose). So this isn’t about choosing between absolute freedom and total coercion; the issue is how best to balance the tradition of academic freedom with the rights of various kinds of institutions to impose requirements on authors in return for such considerations as employment, funding, or publishing services. As it does in so many situations where different parties’ rights come into conflict, the challenge boils down to trying to find the right balance between the legitimate rights of individuals and an obligation to the collective good — or at least, the “collective good” as understood by people who have power over authors.

The second important thing to bear in mind is that when it comes to academic freedom, we are not talking about authors’ legal rights, but about a cultural tradition. In the United States, there is no legal right to academic freedom; instead, there is a deep and longstanding cultural understanding that academics must have the freedom to say and teach what they wish, and to publish their academic opinions and scholarly findings without institutional restriction. When it comes to institutional constraints on authors’ freedom, the question is not “Are these constraints legal?” — invariably, they are. Rather, the question is: how acceptable do we, as a scholarly and scientific community, find these constraints? One important criterion of their acceptability will be the degree of coercion that the policies represent; another will be the amount of public benefit that they offer in return for that coercion.

And this brings us to a third important factor: coercion of authors does not take place in isolation. Policies that restrict authors’ freedom to choose do so with an eye to creating benefits for others. In the case of journals’ and publishers’ requirements that authors relinquish copyright, the idea is that doing so will benefit the journal’s publisher — which, in some cases, will be a profit-seeking entity that seeks to realize commercial benefit from copyright ownership, and in other cases will be a nonprofit entity such as a learned or professional society that seeks to realize institutional benefits for its members. In the case of funder and governmental mandates, the purpose of restricting authors’ freedom is to provide a net benefit to the general public. And universities will typically impose their will on authors with an eye towards realizing institutional benefits (such as those that come with control over patentable inventions, for example) and often public benefits as well.

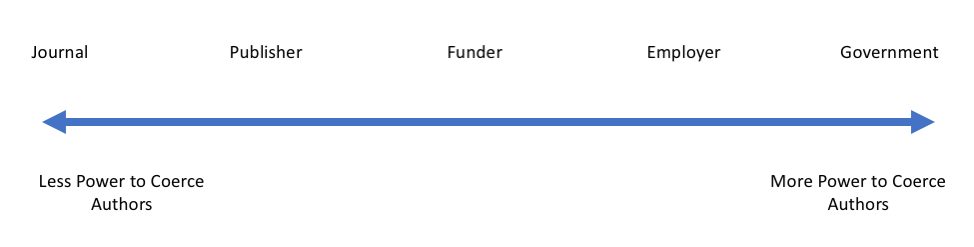

So, given that freedom and coercion both exist on a continuum, where might we place different mandatory policy scenarios along that spectrum?

Let’s look at what I think are the five most common entities that try to constrain authors, which I’ll list here in ascending order of their power to do so (as illustrated by Fig. 1 below):

- Journal. (“If you want to publish in this journal, you must relinquish your copyright in the article.”) The individual journal has relatively little power to coerce authors, because if an author doesn’t like the terms offered by one journal, she can submit to a different one. Of course, the more journals there are in her field that impose similar requirements, the more this competitive dynamic weakens. Which brings us to a scenario one step up on the ladder of coerciveness:

- Publisher. (“If you want to publish in any of our journals, you must relinquish copyright in the article.”) The more journals a particular publisher controls — and the more desirable they are as publishing venues — the more power the publisher has to impose its will on authors.

- Funder. (“If you accept money from us to use for your research, you must publish in [X] manner.”) Funders, of course, control something even more fundamentally important to researchers than publishing venue: the money needed in order to do one’s work in the first place. And since funders both control an essential resource, and are radically less numerous than journals (or even publishers), each one is in a position to wield much more coercive power over authors than any individual journal or individual publisher can. And they are becoming bolder in exercising that power: for example, both the Gates and Ford Foundations now require their funded authors to assign all of their exclusive copyright prerogatives to the general public, and Plan S will forbid funded authors from publishing in roughly 85% of existing journals.

- Employer. (“As long as you are on our faculty, you must publish your work in [X] manner.”) The institutions that employ researchers have even more power than funders do, because they directly control the author’s livelihood. Making a particular mode of publication a requirement of employment is an especially powerful tool of constraint — mainly because, in a tight academic employment environment, authors have little freedom to pick and choose between employers. This scenario is complicated, though, by the fact that college and university faculty typically govern themselves with regard to promotion and tenure, and both establish and enforce the publishing standards by which they’re judged. In other words, when it comes to publishing behavior, it’s the faculty themselves who decide what “you must publish in [X] manner” means, which complicates the issue of coercion pretty significantly. (Can you coerce yourself? Discuss.)

- Government. (“If you produce scholarship as a citizen or resident of our country, you must publish your work in [X] manner.”) Governments have the most power over authors of all of these entities, because not only do they provide many of the employment venues and much of the research funding; they also wield what is the ultimate coercive power in any society: that of the state. To my knowledge, this coercive power is not yet being exercised in the context of scholarly publishing, except by governmental funding agencies: in other words, it’s not actually illegal to publish one’s research behind a paywall, even when that research is publicly funded. (Although governments do have a long history of trying to censor scholars and scientists generally, and we’ve seen particularly egregious examples of this recently in both China and the United States. See, for example, here, here, here, here, and here.) But as governments become increasingly involved in the regulation of authors’ publishing behavior, that possibility becomes less remote and abstract. In this context, it’s worth noting that just a few weeks ago, the architect of Europe’s Plan S was in the United States, working to convince the U.S. government to adopt a similar program.

So, to sum up: freedom and coercion are spectrum phenomena. Different institutional entities have different capacities to force authors do what they want them to do. To say that one is deeply concerned about the coercive behavior of entities that have great power over authors (funders, employers, governments) is not to say that one has zero concern over such behavior on the part of those that have less power over them (journals, publishers). In fact, I do have concerns about publishers requiring copyright assignment; I don’t agree that such requirements are necessary, and I think it would be much better if journals published articles under licenses instead of requiring copyright assignment. But the distinctions between those scenarios are nevertheless important. And the reality of those distinctions raises a critical question: in which of the institutions discussed above do we see a growing inclination to coerce authors and restrict their “full freedom in publication”?

* It is not so defined in other countries; the varying definitions and cultural understandings of “academic freedom” is a topic for a separate discussion. For the purposes of this posting, we will consider these issues in the context of the AAUP definition.

Discussion

42 Thoughts on "Open Access, Academic Freedom, and the Spectrum of Coercive Power"

Many years ago, the university where I taught considered applying its rules about patents to copyrights, reasoning that intellectual property created on university time and in university facilities should belong to the university. (They ceded their rights to one profitable patent when the creator argued successfully that he had thought it up in the shower and it was unrelated to his university research.) They asserted the right to do this and said that the only reason they hadn’t was that there was no money in it–that is, journals don’t pay authors. However, they were thinking that textbooks might be the source of revenue to the university. In the end, the scheme came to nothing–in part because the creative writing faculty would have resigned en masse, and those who wrote textbooks said they wouldn’t bother if they didn’t make money from it.

The point is, I think, that this from the institutional point of view this is about money rather than academic freedom. Though article authors are not paid, universities now realize that some journals make extraordinary profits, and they want a share. How open access affects this equation is beyond me to figure out, but if someone else has the answer I’d be interested.

Money is definitely one reason that an institution might want to restrict the academic freedom of its faculty. But the prospect you mentioned–the loss of faculty to other institutions that don’t impose such restrictions–is indeed a major barrier to imposing those kinds of policies. This, I think, is the biggest reason why we don’t see mandatory OA policies at US institutions: even in a tight academic job market, there’s still enough competition for top-quality faculty between institutions that no one wants to be the first to impose what would be a deeply unpopular restriction. (The only exception I’ve been able to find to this rule is at Duke University–and I think it’s very instructive that Duke’s OA mandate doesn’t apply to faculty, but to graduate students, who of course had no say in its implementation.)

“..the author is being asked to relinquish control over her work..”

Some would ask: is it really “her work”, or does it belong to the funder or taxpayer who funded the research?

Regrettably funders are turning to potentially counterproductive mandates (sticks). There is surly an opportunity for better researcher incentive structures (carrots) that encourage desirable outcomes without undermining the sense ownership felt by researchers.

Twitter: @RichardCDW

Some would ask: is it really “her work”, or does it belong to the funder or taxpayer who funded the research?

Certainly in the US, it is her work, as copyright law explicitly grants ownership to the creator of the work. The only way it would belong to the taxpayer or the funder is if the researcher had signed and explicit agreement stating that all creations were considered “work for hire”:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Work_for_hire

As noted in the comment from Beth Luey above, it is likely that most university researchers would object to such a major change in their employment status.

Note also that nearly every funder has an Intellectual Property policy that leaves ownership of works created with the researcher and their institution. Here’s the Wellcome one for example:

https://wellcome.ac.uk/funding/guidance/policy-intellectual-property

“We do not seek to directly own or co-own IP arising from our research funding. IP created by Wellcome-funded researchers will generally be owned by their employers.”

Here’s the NIH’s policy:

https://grants.nih.gov/policy/intell-property.htm

“Inventions arising from federally funded research projects are required to be reported to the government agency that funded the project, per the Bayh-Dole Act (the Patent and Trademark Law Amendments Act). The Act permits businesses (large and small) and nonprofits (including universities) to retain ownership of the inventions made under federally funded research and contract programs”

And now the Wellcome Trust is a signee of Plan S. I wonder how that sits with their own IP policy?

Personally, I think of research grants as “donations”, and most places allow people to attach conditions to donations. I don’t think that adding restrictions on publication venues goes against academic freedom, since one could still potentially publish whatever he/she wanted anywhere, provided that the research funds (minus salary) came out of his/her own pocket, or from money granted by some other more amenable entity. After all, funders also have their own freedom to choose who and what to fund.

truly surprised this red herring is mentioned yet again on one of the only sites that constantly pushes back on it.

over half the universities in the US are fully private: no taxpayer funds whatsoever.

the public universities typically receive small (and ever falling) percentages of operating funds from state taxpayers. sometimes that percent is as low as 20%, 15%, or lower. does that small stake justify “ownership”?

if states were to assert ownership over the work of faculty (which they never have), this would be an enormous blow to faculty freedom and academia in general. Northwestern could no longer hire away a productive scholar from U-Florida, since U-Florida would own that scholar’s work and Northwestern could not consider it work of the scholar they’ve hired.

and the next move sometimes made by OA advocates on this point–to assert that tax breaks received by higher education institutions because they are non-profit–is a complete nonstarter. For-profit corporations these days receive tax breaks of every kind that often dwarf what universities get. Nobody ever suggests that California owns Apple’s IP and deserves to earn its profits due to the tax breaks the state gives Apple.

i mean, communists do, and I’d be in favor of talking about some kind of socialist economic system, but until we get there, there is just no road to head down where the state owns the work product of professors.

note that there are circumstances where governments pay the entire research budget of specific projects and make the funding contingent on access (OA or otherwise) to the research. that’s an entirely different, specific story, in which researchers openly grant rights as part of the funding agreement. no such agreement applies to professors producing ordinary work on salary.

I think this is an important point — there is a gross underestimation by most parties of the number of unfunded researchers in the US, if not elsewhere. We talk about OA policies that will shut out researchers from developing countries, but it is likely that Gold OA requirements will also leave significant numbers of researchers in wealthy countries on the outside looking in.

Also worth considering how much of a university’s research budget comes from student tuitions — here for example, Duke University charges students $21,000 per year to cover faculty salaries and research costs (https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2014/02/14/277015271/duke-60-000-a-year-for-college-is-actually-a-discount?sc=tw&cc=share).

In theory, if you don’t like a journal’s publishing terms, you can pick a different one, but in practice, the career rewards of publishing in the top journals in your field are too critical to faculty work for us to choose our publication outlet based on altruism before tenure. If we have scruples, we use a green open access option to soothe them rather than choosing a different journal.

Ultimately, open access mandates don’t infringe on academic freedom at all, as long as they allow faculty to use green open access options.

In theory, if you don’t like a journal’s publishing terms, you can pick a different one, but in practice, the career rewards of publishing in the top journals in your field are too critical to faculty work for us to choose our publication outlet based on altruism before tenure.

But there’s a big difference between “top journals” and “only journal.” In other words, I can’t think of any field in which there is genuinely only one journal that will count towards tenure and promotion. (Obviously, the fewer there are, the more constraint is placed on the tenure-seeking author.)

If we have scruples, we use a green open access option to soothe them rather than choosing a different journal.

I may be misunderstanding this sentence, but are you suggesting that it’s unscrupulous to decline the opportunity to make one’s work OA?

Ultimately, open access mandates don’t infringe on academic freedom at all, as long as they allow faculty to use green open access options.

This is only true if you don’t believe that academic freedom includes “full freedom in publication.” If it does, then any policy that constrains authors’ freedom to decide how to publish their work infringes to some degree on academic freedom.

Yes, I am saying that is unscrupulous to decline the opportunity to make one’s work open access. Sometimes we have to choose between careerism and our responsibilities to the public. And we don’t always make the selfless decision.

You’re right, any policy that constrains authors’ freedom to decide how to publish their work infringes to some degree on academic freedom, just not necessarily in a way that is meaningful to a faculty member.

Yes, I am saying that is unscrupulous to decline the opportunity to make one’s work open access. Sometimes we have to choose between careerism and our responsibilities to the public. And we don’t always make the selfless decision.

And this, I think, is an example of one reason why the OA movement has failed to capture the hearts and minds of faculty members. It’s not just disagreement about issues around OA itself, but also this tendency to tell faculty that if they disagree with the goals of the movement itself, they are somehow morally deficient. As long as this message–that disagreement is moral turpitude–persists, faculty will probably keep pushing back. And the only way to overcome their resistance will be to gain power wherever possible, and take the ability to resist away from them.

You’re right, any policy that constrains authors’ freedom to decide how to publish their work infringes to some degree on academic freedom, just not necessarily in a way that is meaningful to a faculty member.

If that’s true, then why not just leave the choice in the hands of the faculty member? Why should the choice be made for her by others?

This is an astonishing remark. I have read it several times looking for some hint of irony.

For the cost of publishing one article OA, I can hire 1-3 undergraduates for a full semester. In doing so, I am (1) helping them pay their way through college and (2) using our grant money more quickly and efficiently than if I had to do all the work myself. How is this unscrupulous?

This refers to free green OA. Not paid Gold OA.

Thank you for this thoughtful piece. I agree that when talking about freedom and coercion, we are not talking about absolutes. However, I’m not sold on the model you present, because it neglects to mention the transfer (or loan) of coercion power from some entities to others. According to the model, journals and publishers have the least coercive power over authors, and employers and governments have the most. However, what if in the employer/government statement “you must publish in [X] manner.” X = “Whatever these journals/publishers say”. This effectively transfers employer and government coercion power to journals and publishers, and ultimately, it might lead to the case that tenure of certain researchers in very specific areas of research rests in the hands of a handful of journal editors.

You’re right; if an institution says “you must publish with [X] journal,” then the institution is using its coercive power to place the author under the someone else’s coercive power.

But I’m not aware of any examples of an institution doing that. As I mentioned in my piece, it’s definitely true that faculties impose on themselves standards for promotion and tenure that include publication in reputable journals. But that’s a very different scenario for at least two reasons: first, where the standard is defined and adopted by the faculty (which is pretty much invariably the case, at least in the US), it can hardly be characterized as external coercion; second, there’s a very big difference between saying “You must publish in Journal X” and saying “You must publish in a journal with a good reputation.” The former is much more constraining on academic freedom than the latter, because it specifies a single publishing outlet rather than a broad characteristic that applies to multiple outlets.

It’s also worth noting here that there are some governments (notably India and, I think, China) that do create lists of approved journals in which their faculties may publish. To the degree that those lists meaningfully restrict the choices of authors, they definitely represent a constraint on academic freedom–as understood in the US, at least. Maybe not as understood in China and India.

In Spain, tenure in public universities is subject to a process of accreditation by a national agency. The criteria are as specific as for example, saying that for physics researchers to get a good research performance review in their tenure application, they must have published at least 130 articles in journals covered by the JCR, and at least 100 of them in journals within the first tertile in their JCR category (I know that JCR doesn’t even display tertiles, but that’s another issue). Would you agree that these kind of criteria significantly transfer coercion power over Spanish researchers from the government to a small number of journals, and that this represents a significant constraint on academic freedom?

The OA movement hasn’t caught on among faculty because it is not necessary to their careers and means extra work for them. I haven’t seen anyone resisting. What I see is faculty who just have too many demands on their time to become fully aware of OA opportunities or follow through with them.

Faculty are educators and the moral imperative of their chosen profession to disseminate knowledge is the same as the OA movement. I believe faculty are genuinely committed to this goal. They are just overwhelmed by so many demands on their time that they can’t also be experts on scholarly communication as well.

The rights of some groups are often limited by regulations that protect the rights of others. Protecting the rights of the public to publicly funded information is one value, and allowing faculty carte blanche is another. Each government, funder, and institution has to decide where their values lie. We don’t always have the right as individuals to choose the lazy path. Sometimes the communities we are a part of look out for the greater good.

The OA movement hasn’t caught on among faculty because it is not necessary to their careers and means extra work for them. I haven’t seen anyone resisting.

You can see faculty resistance, for example, in every OA policy enacted at a US university. Why is it that none of them is mandatory? It’s because the faculties would never have voted to enact them if they were. You also see faculty resistance in the extremely low uptake of OA options on the part of faculty. I’ve seen faculty resistance very directly on our campus, where we tried to introduce an OA policy and the faculty literally, explicitly, told us to stop. The examples are legion.

With respect, Sarah, your position on these issues comes across as remarkably arrogant. Do you honestly believe that the only reason faculty might do something you disagree with is because they’re “lazy”? Do you really believe that when faculty make publishing choices you disagree with, it can’t be because they disagree with you in principle, but has to be because they’re “overwhelmed by so many demands on their time” that they’ve failed to understand things exactly the way you do?

There is certainly faculty resistance to OA mandates. They understandably don’t want their rights diminished. OA mandates are not the entirety of the OA movement. There isn’t faculty resistance to an increase in options for OA.

I don’t think faculty are lazy, but I do acknowledge that it is a lot of work to understand every implication of every OA decision.

Certainly some people may disagree that the public has the right to the knowledge faculty produce. Some people also disagree that citizens of the United States have the right to public education, or social security, or a clean environment. Probably with strong financial motives for these beliefs.

OA mandates are not the entirety of the OA movement. There isn’t faculty resistance to an increase in options for OA.

Agreed on both counts. As long as the options remain optional, I’m not aware of any faculty who object to them.

Certainly some people may disagree that the public has the right to the knowledge faculty produce. Some people also disagree that citizens of the United States have the right to public education, or social security, or a clean environment. Probably with strong financial motives for these beliefs.

For what it’s worth, I have no financial motive for believing that faculty should retain the right of “full freedom in publication.”

Sarah, if memory serves, the author of a green open access article has to self protect his/her copyright should someone infringe upon it. Thus, the author would have to enforce the copyright and if choses to not do so then anyone can use the article as they see fit. Say, someone selectively cites content and in so so doing misrepresents what the author said. It is now the author’s responsibility to take that person to court and force a retraction and removal. Are author’s understanding what they are getting into?

In short, a publisher accepts great responsibility when copyright is transferred because if they do not defend the copyright, the author has legal recourse.

If I am wrong please correct my understanding.

It really doesn’t matter to faculty members if someone distributes their work after they’ve published, as long as they got the credit for the publication from their institution. It just means their work has gotten wider attention, which is a good thing.

If someone misrepresents your work, and they have enough credibility for it to matter, you publish an article explaining why they’re wrong. Scholarship is full of misreadings and disagreements. It’s the nature of studying new things. Scholars go into it with their eyes open.

It really doesn’t matter to faculty members if someone distributes their work after they’ve published, as long as they got the credit for the publication from their institution.

This may be true of some faculty members, but it is certainly not true of all of us. Many of us do care where and how our work is republished, and will resist attempts to take choice away from us in that regard.

This is an important point, which I explored further in a blog in 2012 (https://www.socialsciencespace.com/2012/10/why-open-access-is-good-news-for-neo-nazis/). CC-BY terms do not protect the integrity of a work and the context in which it is used. This is potentially a big deal for those of us in SSH fields where work can carry a high risk of public controversy and injudicious or malicious editing can undermine carefully phrased arguments. I am fine with copyright transfer to my publishers mainly because they share an interest with me in protecting the work against unlicensed abuse and they have much deeper pockets than me to be able to enforce that.

that presumes certain kinds of “work” and does not cover much of what faculty produce and that counts for us as “research.” writers of nonfiction journalism, fiction, poetry, and other forms of for-profit writing do typically object–strongly and rightly–when their work is distributed beyond their control.

Most of what faculty produce is not journalism, fiction, or poetry. These scholars operate in an entirely different publishing ecosystem from the majority of scholarly production.

except they don’t, not in any way that can be clearly defined. they are often the same publishers, the same individuals, the same presses, and the same magazines/journals.

no OA mandates carve out exceptions for work that has traditionally been produced for profit. this is why creative writers have been among the only voices that have stood up against OA mandates. further, the Peter Subers of the world have steadfastly refused when people like creative writers have asked for detailed clauses that make clear that OA applies only to the kind of academic journal articles that have typically been published without compensation. the problem is that there is no coherent way to carve out exceptions–“you must publish in venues that will not pay you, unless you do.” even scientists frequently publish books with for-profit presses. if you look at what has been proposed and even enacted in the UK, it directly cuts against some of the most important and highest-profile work professors do. the current UK push to prevent professors from profiting from sales of their monographs is poison to academia, and to my surprise looks like it may well succeed.

and if you want to know why, ask yourself why the non-professor world does not adopt the model that authors can’t be paid for their work. surprisingly, this creates disenctives for writers, artists, and others who depend on their creativity for their livelihood.

When I have been offered the opportunity to make my work open access, it has come with a price tag: $2,000 for a book review, as I recall. I don’t think turning that down was unethical. I think asking me to pay that much was.

I absolutely agree, turning that down was not unethical. When an author declines to make their work green open access for free, however, that is not the same thing.

i’m in strong agreement with most of this post. but the phrase “relinquish copyright” seems a bit strong from at least the fields I work in (the humanities, broadly).

here, as far as I know, we don’t relinquish copyright: we grant certain limited rights to the publisher that allow it to distribute the article in a number of places. full copyright is not granted to the publisher; they don’t have the right to reprint it in a new venue without our approval, to remove our name as the author, to sell that copyright except the limited aspects of it, etc. the author retains very specific and important rights. further, by custom at least, it is very unusual for publishers to refuse authors the right to publish identical or modified versions of their work in other places (edited collections or single-author collections), or to demand payment for that reprinting (I’d have to check, but I’m not sure that is even provided under the kinds of contracts I usually sign).

Note that under the most common and heavily-promoted OA models, authors basically lose many of these protections, although they are free to republish their own work in their own subsequent publications. Under several OA licenses, namely the ones that allow commercial re-use (none of which, I like to stress, has ever been seriously tested in court, and for good reason, since the author has basically sacrificed all of their IP interests in their work, despite what advocates tell us), the author has no say over whether someone else republishes the work. arguably, and this is one of the things that will never be tested due to the sacrifice of economic rights, even if someone republished an OA piece and violated the “BY” condition, used their own byline, and earned significant $ from it, the original author would have very little recourse because it would be impossible to show that they have directly suffered an economic loss.

Not sure whether this is of interest to anybody, but it appears that my native Sweden in fact does quite explicitly protect the academic “freedom to publish” in law (Chapter 1, section 6, this is a very straightforward translation from the Swedish original):

https://www.uhr.se/en/start/laws-and-regulations/Laws-and-regulations/The-Swedish-Higher-Education-Act/#Chapter%201

In Finland, where I now live and work, there is a less specific paragraph protecting “academic freedom”. I’m not sure what these things mean to law people, but the protection in law is of course meant to shield researchers from various institutional pressures. I doubt that it is meant to be overridden as easily as the OA provisions from Swedish founders joining Coalition S.

Note that this comes with the significant caveat that I’m in no way a legal expert (but will definitely try to get opinions from people who are).

It is arguable that there are also ways to read the constitutional protection of academic freedom in Germany in the same way. It is notable that the Federal Government has not rushed to endorse Plan S which suggests that they may share my interpretation. Of course, there is a big difference between having a right and having the resources to enforce it…

In other writings, Rick, you’ve suggested that it’s problematic if not dangerous for individuals/organizations to act outside of their host institution’s mission (“…we will have an ultimate obligation to act more like soldiers than like revolutionaries. Libraries that fail to do so will inevitably lose their institutional support – and with good reason.” https://insights.uksg.org/articles/10.1629/uksg.230/).

Why wouldn’t that same obligation apply to the divisions and employees of a grant-making institution? Why shouldn’t the Gates Foundation, Wellcome Trust, or a government agency base the terms of their spending on their organizational mission? These bodies don’t fund research for the sake of funding research, after all; they have priorities and fund research in order to advance those priorities.

Matt, what you’re quoting is a paper in which I argued that when libraries fail to align their practices and strategic goals to those of their host institutions, they run the risk of losing support from those institutions. In that context, the library is an agency of its university, not an independent entity. The same would definitely apply to the subdivisions (and employees) of a grant-making organization. Were you under the impression I was suggesting that employees of, say, the Gates Foundation should go rogue and refuse to carry out its OA policies?

(Apologies if I’m not fully understanding your question.)

No, I’m asking why should a government agency, foundation, or other funding source refrain from implementing policies that advance their mission?

You’re suggesting here that it is problematic for governments and funding agencies to exert coercive power in opposition to academic freedom, via open access mandates and similar policy actions. Yet these policy actions are typically announced and framed as actions in direct support of strategic goals or an organizational mission.

So what is the problematic aspect here? Are you concerned about organizations acting in support of their strategic goals, or about organizations adopting strategic goals which value public access to information over traditional publishing practices?

No, I’m asking why should a government agency, foundation, or other funding source refrain from implementing policies that advance their mission?

Ah, okay. In that case, the answer is “in the interest of preserving an author’s academic freedom.”

You’re suggesting here that it is problematic for governments and funding agencies to exert coercive power in opposition to academic freedom, via open access mandates and similar policy actions. Yet these policy actions are typically announced and framed as actions in direct support of strategic goals or an organizational mission.

I don’t understand your use of the word “yet” here. An organization’s strategic goals and mission can certainly be pursued in a manner that imposes coercive constraint, in a problematic manner, on those over whom they have power.

Are you concerned about organizations acting in support of their strategic goals, or about organizations adopting strategic goals which value public access to information over traditional publishing practices?

I’m concerned about organizations pursuing their strategic goals in a way that coercively undermines the academic freedom of their funded authors. The high-mindedness of their intentions in doing so is not irrelevent, but it doesn’t make the problem go away either.

Interesting. So you are here arguing that organizations should choose to align their resources in support of something which is not a strategic goal (i.e., academic freedom as you have defined it here), rather than in support of something which is a strategic goal, if the two are in conflict? Maximizing access to funded research is, after all, in direct conflict with the subscription publishing model, which is based on denying access to anyone who does not pay.

Or are you arguing that these organizations’ strategic goals should include preserving the ability of scholars to get money no matter where they choose to publish?

As always in my discussions with you, Matt, I’m going to express my position using my own words rather than letting you try to maneuver me into an endless string of false choices.

What I’m suggesting is that when funders choose to exercise their power over authors by limiting their publishing options, that represents a restriction on academic freedom that needs to be discussed broadly and in an above-board way. Authors need to be aware of what’s going on, and need make their voices heard — whether in support or in opposition, as they see fit. Funders, of course, are under no obligation to listen to authors; they have the money, which means they have the power, and they have every legal right to use that power to impose their will on those who rely on them for money. But it’s also appropriate for the larger scholarly community (which consists mainly of authors) to know what’s going on and to make their voices heard if they have opinions about such policies.

Journals implicitly value an article at $0 or a negative figure, if there are page charges. Yet if one opts for open access, they charge an outrageous fee. Which is it, guys? Is my article worth nothing or something? Shouldn’t you pay me for NOT choosing open access? Or–my preference–not charge me for choosing OA?