In times of controversy, it may be tempting for an author to remain silent and let others speak. Yet in science, silence is often an indication that something has gone awry which cannot be explained. Rather than placating the public, an author’s refusal to speak has just the opposite effect: Silence generates skepticism and undermines trust, not only of the paper itself, but of the authors, their institutions, and the journal that published their work.

After weeks of silence from the authors of a new paper, “Does Tweeting Improve Citations? One-Year Results from the TSSMN Prospective Randomized Trial” (Annals of Thoracic Surgery, 3 June 2020), I published a critique, pointing out various errors, omissions, and inconsistencies in their work. Keeping in character, the authors refused to respond, either with answers or with their dataset.

After much work, I was able to recreate their dataset from an appendix to an earlier work. Using their title list, I matched each paper to its citation performance in the Web of Science (Clarivate Analytics). I also looked up the article type for each paper on the participating journals’ websites. For the record, I am willing to share this dataset with anyone who asks.

Following the authors’ methods stated in their paper, I can report the following results:

First, the papers listed don’t match those described by their methods. The authors described selecting 112 “representative original scientific articles published from 2017-2018 in the Annals of Thoracic Surgery and The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery.” The authors also explicitly excluded particular article types: “Articles that were not reporting on original scientific research were excluded, i.e. reviews, editorials, letters to the editor, and case reports.” However, their list of selected papers included 3 Reviews and 16 Editorials, one of which was entitled, “How Andre Agassi helped me during my cardiothoracic surgery training,” an inspiring personal note on how a tennis star helped the author persevere through his training. This paper was assigned to the Control group, as was another Editorial that was simultaneously published in 3 separate surgery journals [1]. An author of this thrice-published Editorial was Mara Antonoff, the corresponding author of the tweeting study. Perhaps silence, in this case, was a much safer response than pleading ignorance.

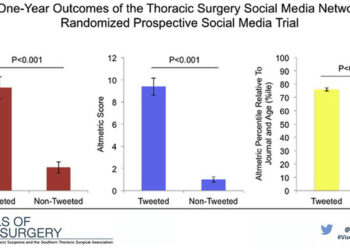

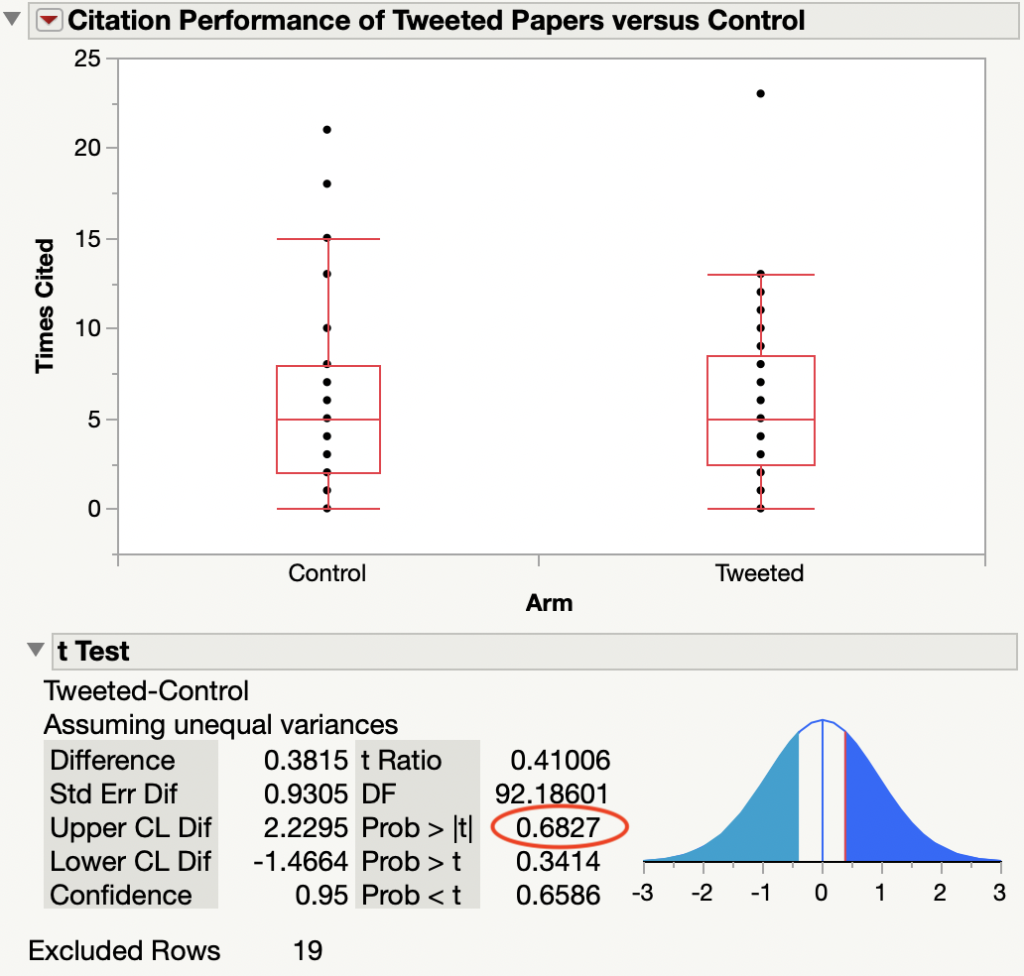

Second, and more importantly, I detected no citation differences between the intervention (Tweeted) and Control arm of their study. Comparing citations accrued at a median of 861 days (2.4 years) from publication, Tweeted papers received 5.5 citations on average compared to 4.9 citations for the Control group — a difference of 0.6 citations (not significant, p=0.47). Removing the 16 Editorials and 3 Reviews from the dataset, the difference in citation performance gets even smaller: Tweeted (5.8) vs. Control (5.4), for a difference of just 0.4 citations (not significant, p=0.68), Figure below.

In their paper, the researchers reported a change of 3.1 citations for the tweetment group and 0.7 citations for their control group — a difference of 2.4 citations (p<0.001) in a period of just one year. They also reported that tweeting created a citation effect was 9.5 times the size of the control. It is difficult to believe how such a large effect could simply vanish.

Authorship comes with benefits and responsibilities: Both are necessary for the system of rewards in science to operate effectively. When authors are openly willing to derive benefits but accept no responsibilities, there is only one recourse: Editors must step in as arbiters and either compel the authors to clarify their claims or label their paper as untrustworthy. This case is understandably complicated, as both the first author (Jessica Luc) and corresponding author (Mara Antonoff) are both members of the journal’s editorial board.

But someone needs to speak up, even if deep conflicts of interest are at the root of this silence.

[An update to this investigation was published on 3 August 2020, Tweeting-Citations Authors Speak, Finally]

Notes:

1. “Transatlantic Editorial: Thoracic Surgeons Need Recognition of Competence in Thoracic Oncology” was simultaneously published in The Annals of Thoracic Surgery, The Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, and The European Journal of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "Reanalysis of Tweeting Study Yields No Citation Benefit"

Thanks Phil. I don’t understand this comment “In their paper, the researchers reported a change of 3.1 citations for the tweetment group and 0.7 citations for their control group”.

It’s strange to see a report of a change for the control group – it’s an increase of 0.7 citations relative to what?

Great work, Phil! There is at least one publication (https://explorer.altmetric.com/details/43339115) in the non-tweeted arm, which actually received tweets and retweets during the focused tweeting period (4-17 June 2018) according to Altmetric. The tweet came on the 5th of June from the official account of Annals of Thoracic Surgery (https://twitter.com/annalsthorsurg), and it was retweeted several times during the following few days. There are other publications in the non-tweeted arms which have received several tweets outside the focused tweeting period. This shows that it is very hard to separate the treatment/non-treatment arms in this case, because it is not possible to control who and when will tweet about the articles.

Thanks for the follow-up analysis, Gabor. For this experiment, the intervention was limited to a single tweet from the first author (Jessica Luc) and retweet from the other TSSMN delegates. All other tweets, even from the journal itself, are not considered part of the intervention.

This is a very weak intervention. And given what we know about the effect of social media on citations, we shouldn’t be surprised that such an intervention has little (if any) effect.

from their Study Protocol:

In brief, 4 articles were prospectively tweeted per day by a designated TSSMN delegate (JL) and retweeted by all other TSSMN delegates (n=11) with a combined followership of 52,893 individuals and @TSSMN for 14 days from June 4 to June 17, 2018.

Excellent analyses and posts. So what’s next? Trim these two posts down to letter-to-the-editor length and see where that goes? That would likely provide good material for another post, but I’d be highly impressed and surprised if the editors publish it forthwith. Crickets would be my guess, based on David Allison’s prodigious attempts to publish critical letters to the editor, which usually seek to take authors to account for their statistics. Or they might just send you away in rounds of review, such as with “How to Publish a Scientific Comment in 123 Easy Steps.”

When I started reading your initial post I assumed it would be another police report of a p-hacking misdemeanor, where someone bashed their data into “significance.” After all, it makes sense that Tweeting and the like might have some effect – promoted articles would be seen more, seen articles read more, and read articles cited more. But a 9.5X effect size? This is more than a garden variety case of confirmation bias and selective statistical testing. Hopefully the next publicity seen for Dr. Antonoff’s study (after your expeditiously published letter to the editor (ha)) will be in Retraction Watch. Kudos.

Yes, the analysis reveals much, much more than p-hacking. In small datasets, there is a reasonable chance of finding a big difference, especially if one arm of the study includes a single extreme outlier, as was the case in the TrendMD reanalysis. If the researchers compared the performance of each group by simply calculating their mean, this could explain a large difference.

However, the Figure shows no evidence of extreme outliers. Both groups performed about the same, whether you do a simple (inappropriate) t-test, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test, or just eyeball the data. I don’t know how the researchers could even argue that they found a massive difference at year one that could not be replicated at year two, given that citations are cumulative.

If the authors were willing to explain and defend their work, we could get somewhere. At present, there is sufficient evidence to conclude that the paper is untrustworthy.

Absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence, a lack of a significant (alpha of 0.05?) p-value does not always indicate no evidence for the null, it depends heavily on the sample size. Best you can say is that there is currently no evidence to support a citation benefit in tweeting, until you look at either some kind of test of equivalence like TOST or its variants from Lakens and others or a Bayes Factor approach. Admittedly, looking a the box plots there is likely no effect here but claims, either way need evidence.

I appreciate your response, Bryan, but you need to put the reanalysis in context. The extant literature on the effects of social media on citations shows little or no difference, meaning the theoretical difference is zero. However, the authors made some exuberant claims in their paper that looked suspect, and were unwilling to explain or defend their paper. A reanalysis of a dataset built by their description also shows no difference, which supports the null hypothesis. Granted, the distribution of citations is known to be skewed and the authors used a simple t-test, which is based on normally-distributed data. It was important to follow their statistical methods in order to discount their claims. A non-parametric (e.g. Wilcoxon) test should have been used, but it, too, shows no difference.

In sum, it behooves the authors @JessicaLuc1 and @maraantonoff to defend their paper and share their dataset. If not, the editors of the Annals of Thoracic Surgery @annalsthorsurg have an ethical duty to retract this paper https://doi.org/10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.04.065

With a theoretical difference of zero and using the only T statistic I can easily find (in figure 1), using a JZS Bayes Factor and a sample size of 112 for each group, the best we can see is BF01 = 6.34. In other words, the data indicate that the null hypothesis is about 6 times more likely than the alternate. This is not exactly overwhelming evidence in favour of the null. Adjusting the prior on effect sizes to make it more precisely centred on an effect size of zero does not dramatically change the Bayes Factor (this should make it harder to shift one’s belief away from there being no effect). I agree the data need to be openly shared and the authors and journal should respond and it sounds like the paper should be retracted. All that being said, a non-significant p-value does not in itself distinguish between there being support for the null or there being insufficient evidence either way (equivocal). This is true irrespective of what the expected value of the population parameter is or how wrong the original analysis. My conclusion from this data is that even selecting a strong prior of there being no effect of social media on citations the best you can conclude from this data is weak evidence for no effect. More data is needed to make a definitive claim, doing otherwise is dangerous, even if the original analysis is broken.