In yesterday’s post, we wrote about why publishers should care about persistent identifiers (PIDs). Today, we are broadening our scope to discuss the benefits of a fully PID-optimized research ecosystem, not just for publishers, but for funders, institutions, vendors, and of course, researchers — and, importantly, how they stack up against the costs…

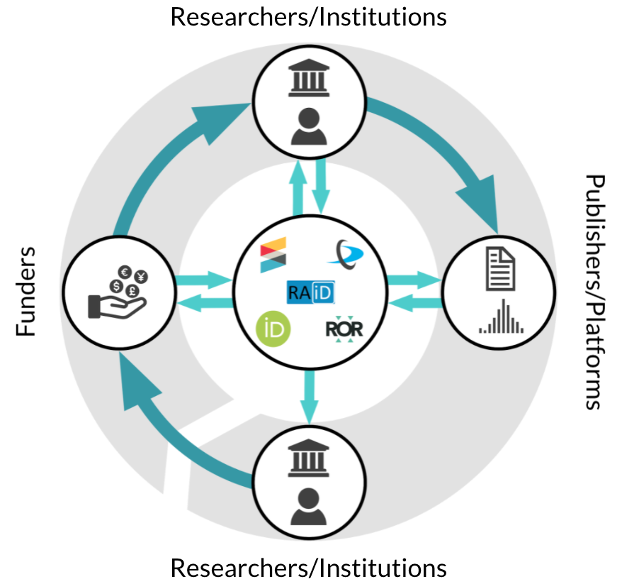

Before we get into that analysis, we need to ask what we mean by a fully PID-optimized world? Essentially, it’s a world where persistent identifiers are registered, used, and shared at all points in the research lifecycle. To be most effective, PIDs would not only be created for the people, places, and things associated with research, but would also be collected and used by funders, institutions, and publishers, at the earliest possible point in the process. For example, ORCID IDs for researchers would be captured by funders during grant application; grant IDs would be captured by institutions at the point of award; and so on. In addition, as we noted yesterday, PIDs are more than just identifiers, they also have metadata associated with them — and, vitally, that metadata should include other associated PIDs. This is often already the case, for example, for DOIs associated with ORCID records, but it needs to happen much more broadly and more completely. Think about collaborators being associated with grants, or ROR identifiers for institutions being embedded in article metadata. This early capture and association minimizes the manual entry of information and maximizes the opportunities for it to be reused.

The image below is a representation of the PID-optimized workflow. If you click on it, it’ll take you to a Zenodo page with a more detailed and annotated infographic.

But getting from concept (infographic) to reality (implementation) in a multi-stakeholder environment is easier said than done. For one thing, there are costs associated with PID adoption; for another, the benefits aren’t always clear to the decision-makers responsible for agreeing to those costs — they want proof of a worthwhile return on their investment.

There is plenty of evidence for the practical value of linking research objects together, like this article by Colavizza et al and this more recent one about real-time bibliometrics for COVID-19. There have also been several efforts to compare costs with financial value of PIDs and PID integrations (see here, and here).

The UK PID roadmap

Last June, Alice shared details of Jisc’s multi-year program exploring how PIDs can be used to reduce friction in the ongoing transition to open research, including their 2019 PID Roadmap for open access to UK research. This report identified five priority PIDs, seen as most likely to contribute efficiency gains across the UK — and global — research information network:

- DOIs for outputs (Crossref and DataCite)

- Grants (Crossref)

- ORCID IDs for people

- RAiD (Research Activity iDs) for projects

- ROR (Research Organization Registry) IDs for organisations

The report also recommended the formation of a UK PID consortium, and the establishment of a governing council, whose responsibilities would include consortium oversight and management. That council is now in place — the newly-formed Research Identifier National Coordinating Committee (RINCC). However, before moving ahead with the proposed national consortium, the stakeholder group that preceded the RINCC requested a cost-benefit analysis, to help build a sound business case for the investment required. The full report is now available, and, in addition to the analysis itself, it also includes a brief review of other PID analyses, several case studies, and a handy Excel model that enables any institution to enter its own data and derive an estimate of cost savings, based on its scale and structure of support for research (full disclosure — we are co-authors of this report, together with MoreBrains colleagues Josh Brown and Fiona Murphy). Although this analysis focuses on the UK, our hope is that other communities and organizations will use the same methodology to evaluate the costs and benefits of widespread PID adoption.

As mentioned in yesterday’s post, there are three broad areas of benefit for widespread adoption of PIDs:

- Metadata exchange

- Automation of processes

- Improved business insight and analysis

The cost-benefit analysis focuses primarily on the first of these — largely because it is the easiest to measure — so the benefits (financial and other) of a fully PID-optimized world would, in fact, be even greater.

So, without further ado, here are some of our key findings!

Finding 1: Widespread PID adoption will generate significant cost savings

To be honest, when we first started this work we didn’t have any idea of the scale of potential cost savings a PID-optimized research world would enable. There is a (largely anecdotal) sense that researchers and administrators spend a lot of time keying and rekeying information that could be automated, so we figured that PID-enabled integrations would probably at least pay for themselves. Working with Paul Clayton, Financial X-ray Lead Accountant at Jisc, who did the financial modeling for this analysis, we were able to determine that an estimated £5.67M could be saved in the UK over the course of five years, if PID adoption targets of 67% by year 3 and 85% by year 5 can be met. This is based on conservative estimates and includes the cost of setting up and running the PID consortium. We assumed only one metadata reuse per research output. This is a deliberate underestimate so in reality, cost savings are likely to be higher.

It’s important to reiterate that our modelling predicts that the financial benefits of PIDs are dependent on the level of adoption across the ecosystem. The PID-optized world is effectively a knowledge graph or network of objects and, like many networks, the bigger it is the more valuable it becomes to each participant. So PID adoption efforts must include funding for education, outreach, and community participation.

Finding 2: It’s not just about direct cost savings

Although it’s always good to be able to demonstrate significant cost savings, we believe that there are other, less tangible benefits of a national PID consortium (not to mention a globally PID-optimized research lifecycle), which are equally — if not more — valuable in the long term.

The UK’s primary governmental research funding body (UKRI) currently spends £3.2 billion a year on what it calls pioneering ideas. Reducing unnecessary administrative work and increasing efficiency by just 2% would free up over £60 million for research. That’s not to mention that every £1 spent by the government creates £7 of benefit to the economy. As we mentioned in yesterday’s post, global research and development spend is $1.7 trillion. With so much at stake, especially now as the world faces multiple crises from climate to public health, making the best use of that money is more important than ever!

On a more immediately practical level, a consortial approach will enable UK research institutions to have greater influence with vendors, and to ensure consistency of approach to PID use, leading to improved portability of metadata and workflows and increased ease of collaboration. It will also ensure that “no research institution is left behind.” While the national PID strategy and implementations could disproportionately favor the largest research-intensive institutions, the benefits will only be fully realized when everyone is involved. PID adoption at smaller and more specialist institutions is critical to the success of this initiative, and the consortium will facilitate their participation, by reducing duplication of effort, improving documentation and standardization, and providing community resources to assist local IT staff and administrators.

Publishers were out of scope for this analysis but, as mentioned yesterday, a PID-optimized world would give them access to more complete, more accurate, and more timely contextual information about their content. It would enable them to more easily gather better information that can be used both to increase discoverability and for market analysis.

Finding 3: Quality versus quantity

The time saved through efficiency gains in a PID-optimized world won’t (and shouldn’t) always translate to reductions in time spent, for example, on reporting. Instead, researchers will be able to spend this extra time on higher value work, such as narrative/contextual information, or additional reporting on innovative outputs and outcomes. We know from this ORCID ORBIT report that, “Funders see a need to automate … so that the limited time and effort researchers have can be focused on describing impacts, relationships between activities, funding, and subsequent activities rather than providing simple factual data” (disclosure — Alice is one of the authors). By improving the quality of reporting in this way, investment in PIDs will support better, evidence-based decision-making.

FInding 4: Community buy-in is essential

Without wanting to downplay the technical challenges, they’re less of an issue than the culture and behavioral changes that will be needed to achieve widespread PID adoption. High-level commitment to integrate and support all five priority PIDs is part of the answer. In our stakeholder interviews, everyone (publishers included) saw this as essential to ensuring buy-in and avoiding any increase in administrative burden. But, to be successful, all stakeholders need to be equally convinced, so clear messaging—and, as noted above, evidence—of the benefits are needed. Taking researchers as an example, we know that many of them already choose to use PIDs when they see the benefit of doing so, such as the automatic updating of their publication lists in Researchfish or the automatic addition of their outputs to their ORCID record via Crossref and DataCite.

FInding 5: It takes a village

Cross-sector collaboration is also essential to achieving the full benefits of a PID-optimized world—and, of course, to ensuring that all stakeholders benefit from it. While this analysis focused on institutions, it’s clear that funders, publishers, and the service providers that support them also stand to gain from widespread PID adoption. That means collecting—and making openly available—PID metadata that is as complete as possible from the earliest points in researcher workflows (e.g. grant application), so that publishers and content platforms can incorporate it in their platforms and systems, add publication metadata, and make it available to other stakeholders.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Making the Case for a PID-Optimized World"

Another great read and a truly compelling case for the use of identifiers. However it is sad that the work excludes identifiers for research objects as opposed to data or people. RRIDs are now in heavy use in the biomedical literature, and they cover research reagents and resources.

It would be great to understand how much money is saved when investigators are able to quickly track down the reagents that they need to replicate a portion of the experiment. For antibodies, which usually take 6 weeks to optimize and cost $300-800, 50% do not work. So having insufficient information adds a tremendous burden to labs! How much money, time, and post-doc gray hair can we save by having this information easily available inside of the manuscript?

RRIDs don’t seem to have any kind of markup associated with their usage. As far as I know if it’s in the article text then a crawler will eventually pick it up and report back to scicrunch (?). I’ve never seen JATS XML markup for it and it’s not in any metadata schema I know of. So in that respect, is there anything even required from the publishing community except to ask authors to put them in and gently suggest that they use them if missing?

Thank you for the comment Anonymous.

We are working with the JATS group to start the process of adding markup, we have hit a snag or two, but the goal is indeed to bring this into proper article metadata in JATS at some near-ish point so they would no longer depend on a single group or the good graces of google scholar.

For the time being, we have a funded project to pull them semi-automatically.

https://hypothes.is/users/scibot?q=group%3A__world__

Should be in the ~300K public RRIDs, so far, which we would love to add to the article metadata, once snags are resolved.

Of course, getting these into the paper in the first place is possibly most important use case and in that case, yes it would be lovely to increase author awareness that they can actually help them do better science, including steer clear of contaminated reagents (e.g., https://elifesciences.org/articles/41676). Some journals do go much further than gently nudging authors, they are requiring RRIDs as a condition of publication (seemed to go over ok at Nat.Protocols: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41596-020-0334-4 ).

Thanks for the reminder about RRIDs Anita – there are a number of other very useful PIDs (including RRIDs!) that we very much hope will also be more widely adopted. But, as Phill noted in response to a similar comment from Martijn Roelandse yesterday, we started with just the five priority PIDs that are likely to deliver the best return on investment soonest. You can read a bit more about the process in this post from last year: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2020/06/29/the-uk-national-pid-consortium-a-pathway-to-increased-adoption/