Culture wars have proven a successfully-repeated trope in political campaigns. This history of censoring content for political purposes dates back well into the 19th century with fights over information about slavery and then the Comstock Act seeking to limit vice. It continued into the 1920s, with the Scopes Monkey Trial. In the 1950s and 1960s, as waves of anti-communist fears gripped the nation, the perceived “left-leaning bias” in Hollywood led to blacklists, and efforts to “protect children” through the formalization of the Hays Code into the current rating system for movies. In the 1980s there were hysterical concerns about Dungeons and Dragons (later to become a plot point in Stranger Things) but also in music, eventually leading to the “Explicit Lyrics” stickers on album covers. Today, these culture wars are heating back up and it is well past time that the publishing community begin to engage in the battles. Last week, in a court filing against a school district in Florida, a brave band of authors, parents, PEN America, and a single publisher, Penguin Random House (PRH) have entered the fray. Many other in the publishing community should stand up behind them.

The court filing from last week details a case alleging that the actions taken by the Escambia County School District in Florida which are claimed to be political infringement of the rights of authors, publishers, parents, and students. In the filing’s 59 pages, the plaintiffs outline how one activist in particular, supported by the school district leadership, has systematically sought to limit access to materials focused on race, gender, sexuality, or other “woke” themes. While some of the books in question do raise mature themes and can be challenging to users, often that is what good literature does. The purpose of fiction is not solely, as one of the complainants asserts, “simply to ENTERTAIN” (emphasis retained as related in the filing, p. 39).

This case is more than just a single school district

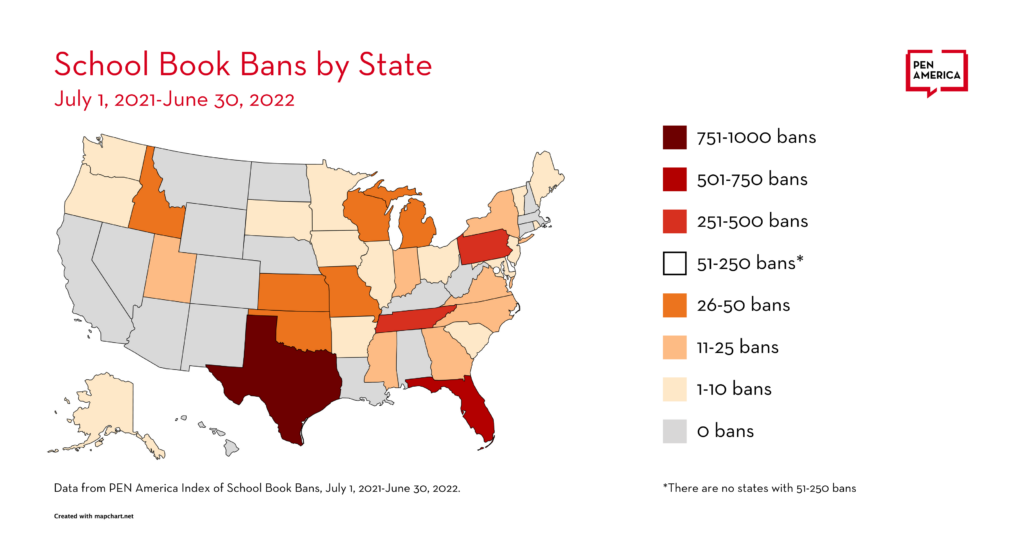

The plaintiffs describe what by all accounts appears to be a coordinated campaign across dozens of states, generally targeting a small subset of the few millions of books published each year. According to data from PEN America in the year ending June 30, 2022, more then 40% of book bans in the US were focused on books describing or including LGBTQ issues or characters. A further 20% involved issues of race. One might dismiss those few hundred books as “fringe titles, full of obscene or problematic materials unfit for children” that might be best kept from schools. Without acquiescing on that point, the problem is that these processes are increasingly being directed at an ever wider range of content.

The Pen America report, Banned in the USA, describes how these bans are “increasingly affecting a wider swath of titles, including those that portray violence and abuse (44%), discuss topics of health and wellbeing (38%), and cover death and grief (30%).” To give one a sense of scale, in the 2022-23 school year, 1,477 instances of individual books banned, affecting 874 unique titles, which is up 28% in just the preceding 6 months. One can reasonably expect that the pace and ferocity with which these bans are pursued will only increase to coincide with the coming political campaigns in 2024.

It is worth stressing that this campaign to reinvigorate cultural wars around book banning is an explicit and coordinated nation-wide strategy. Most of the book bans outlined in the suit mirror lists and rationales provided by national campaign sites supporting limiting access to content. Often times, these vaguely worded critiques are provided to school districts or public libraries where there is little chance the complainant has actually read the book in question and sometimes, the complaints are directed toward books that aren’t even held by the library in question.

There has often been an intentional misunderstanding and conflation about the distinctions between what is taught in classrooms and what is simply available in the library. As described in the Pico ruling, libraries are places distinct from the classroom, where children’s self-directed interests can lead to exploration outside of the standard curriculum. The supporters of book bans often bounce seamlessly between the two, forgetting this key distinction and making it seem as if they are concerned about the books being in the classroom, when the vast majority of the time, they are not.

Also, often the “worst” examples of literature are cited for justifying the principle, which is then taken to the extreme. One might argue that The Perks of Being a Wallflower by Stephen Chbosky is a challenging title that is not appropriate for a third grader, as its subject matter is mature. Yet somehow the same rationale is given for removing Diary of Anne Frank, or the Handmaid’s Tale. Historically, this is a variant of the same arguments that were made for banning Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1851 and many others.

Since a 1982 Supreme Court ruling in Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico, the prevailing opinion of the Court has held that “Local school boards may not remove books from school libraries simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” Appellate courts have reiterated a similar basis for this rationale, even while turning aside other claims. For example, even while dismissing the viability of the students’ claims in the Seventh Circuit in Zykan v. Warsaw Community School Corporation, the court was careful to note the ruling was “not to say that an administrator may remove a book from the library as part of a purge of all material offensive to a single, exclusive perception of the way of the world.” However, the Pico ruling was somewhat muddled by the 5-4 split in the decision, with a variety of Justices split on which rationale they preferred for their decision. This could leave open the possibility that the decision in Pico could be ripe for reconsideration.

It is also worth noting that the Supreme Court has, of late, decided that no long-established precedent is not worth revisiting, so there is no guarantee — as much as one might want one — that the Judiciary will continue to rely on the precedent of Pico. One might believe this precedent will remain, and I, for one, hope that it does. However, while a good court strategy is wise, there is likely more that needs to be done to curb these efforts to control what readers may find in a library.

Why should publishers care?

These actions pose a specific threat to the business of content providers and other service providers for the school and library markets. Here are just a few high-level reasons why more publishers publishers should care:

- The resources directed toward bans, fighting bans, and responding to requests to remove or sequester content deflect resources that could be spent on content (it’s bad for business). It leads to higher litigation costs, to insurance costs, etc. It wastes staff time and distracts from management oversight of more important issues.

- A rating system, as has been proposed on several occasions and as has been adopted by other industries would be expensive and problematic to employ.

- Authors, in whose behalf publishers stand, need allies and it is incumbent on publishers to support and defend the authors whose content is being censored.

- There is no clear line between educational content and “explicit” content, because to educate or research, sometimes these topics can or need to be detailed and range into topics some people would prefer not to discuss. This is particularly true in some areas of scholarly publishing.

- Core to the business of distributing ideas is the notion of intellectual freedom and the right of people to read the content being distributed. Limitations on this right will inevitably diminish the market for content in some measurable way.

Advocacy Organizations Can Help, but they too can do more

The publishing industry has historically played a leading role in the fights against book bans and censorship. The Association of American Publishers has as one of their three key policy areas “Protecting Freedom of Expression and the Free Exchange of Ideas”. And yet, there is no statement about the Pen America et al., case by AAP on either their News or Blogs sites (as of May 23rd). It is not the pace of a response on this particular point that is most troubling, the issue seems to have fallen off the radar entirely in recent years, despite the above-mentioned flood of attempts to ban materials. If you scan through the past couple of years of AAP’s press releases and blog posts about its activities, you might notice a decided lack of focus on supporting the public’s access to materials unfettered by attempts at state and local bans. For example, it appears the last time AAP publicly supported Banned Books Week activities was six years ago in 2017.

AAP and many other organizations have played a role in the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC), which has regularly highlighted and objected to a variety of book banning activities. This work by NCAC has been helpful and is much appreciated. While political strength can benefit through coordination, joint statements can also diminish perception of the breadth of a position’s support if the co-signers on the statement simply leave the promotion of the position to the central body. This seems to be part of the problem with NCAC position statements and activities. The community should do more than simply co-sign NCAC statements on these issues.

Politics, especially in Washington, are very sensitive and organizations need to be careful how they direct their resources. To achieve desired ends one often needs to find a way to balance interests among people who might not normally agree. The copyright-focused industries have balanced those interests reasonably well over the years, finding common cause with a very diverse set of supporters. It makes sense for an organization like AAP to be bipartisan and find ways to work across the aisle to achieve its mission. However, when its stated missions collide, it is important to stand with one’s principles. If freedom of expression and intellectual freedom are indeed primary goals of the organization, as it proclaims, it should draw more attention to these growing problems, not just in DC, but among the many states.

This should not be read as a swipe at AAP here, as many publishing organizations could also do more. PRH has resources to pursue this case that many other publishers do not, but that is not a reason why it should stand alone in these fights. Many other organizations, big and small, publishers and other content providers in our community, are negatively impacted by these actions to suppress the free access of information. Of course, it doesn’t make sense that every organization do so publicly, forcefully, as PRH has done in a court of law. There are many ways to show our collective support and commitment to our principles. It would be wonderful if more in our community provide more than quiet, tacit support.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "The Publishing Community Should More Actively Oppose Book Bans"

Todd my hat is off to you. I have been endlessly dissapointed with the quiet across the publishing world as the culture wars have heated up. Tell me how many articles, posts, blogs, forums, etc. you have read from publishers speaking out??? Here is a link to my very public position on the subject from March 2022: https://livedplacespublishing.com/blog/learning-belongs-in-the-library-%E2%80%94-on-critical-race-theory-and-book-banning-publishers-speak-up!

Well said, Todd! Thanks for saying this out loud.

The irony here for those who support banning books (not that the irony of so many right-wing comments and actions gets much traction) is that the alternative for young readers is to scroll on their devices in pursuit of information that could be found in books in a context that has the guidance of a librarian or other adult in an educational setting. So where on the continuum is banning books also an attack on publishing?

Interestingly, whereas attacks on books in libraries tend to come from the Right, direct attacks on publishing (and bookselling) often come from the Left. Overwhelmingly, it’s organized conservative groups that challenge books in schools and libraries. But recently we’ve seen significant examples of the Left trying to stop books from being published, calling for them not to be sold, and retroactively censoring books already published.

Before I get pounced on for pointing this out, please note that I’m not saying that Left censorship is just as big a problem as Right censorship, or that the Left does it just as much as the Right does. I’m saying that Left censorship is also a problem, and that censorship is not less pernicious when it comes from those we agree with ideologically.

Publishing should be trailblazing, risk-welcoming, comfortable with all sides of an argument, free of political influence, and committed to creating thinkers who, as Krishnamurti describes it, ” … are [free of] thinking [that] is conditioned, [because] our beliefs and dogmas have no value at all …” if they are not broadly informed.

That said, I have no problem with a publisher adopting an ideological stance and saying “This is our house position.” There’s no reason why Verso should have to publish right-wing books or Regnery left-wing ones. But we need an ecosystem in which both Verso and Regnery can flourish, and when people try to keep either one from publishing ideas they don’t agree with, we need to call that out.

Thank you, Todd, for this post, and I completely agree with you that publishers and academics should be speaking out more against this wide-ranging censorship. I also urge anyone who wants to contribute financial resources to consider the Freedom to Read Foundation (more info at https://www.ftrf.org/ ), which is “a non-profit legal and educational organization affiliated with the American Library Association. FTRF protects and defends the First Amendment to the Constitution and supports the right of libraries to collect – and individuals to access – information.” School and public librarians are under fire, being threatened with violence, arrest, and incarceration for simply doing their jobs to provide resources and information to the public. See https://www.everylibrary.org/its_very_real for some chilling news. How long will it be before those wanting to shut down access to information start targeting academic libraries and librarians in a serious way?

In a related development: “Illinois sets precedent in becoming the first state to ban book bans” https://goodereader.com/blog/e-book-news/illinois-sets-precedent-in-becoming-the-first-state-to-ban-book-bans?utm_source=feedly&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=illinois-sets-precedent-in-becoming-the-first-state-to-ban-book-bans&utm_source=New+Items+and+Posts+from+Against+the+Grain&utm_campaign=dbc5ea4823-RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_34489e508f-dbc5ea4823-174630079