Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Janet Salmons. Janet is a free-range scholar. She edits the Substack newsletter, When the Field is Online, and is the author of 12 books, most recently Doing Qualitative Research Online (2022).

I thought I was a scholar and a writer, but I found out I’m just a link in generative AI’s content supply chain. So far, three of my books have been swallowed up without my consent, and I assume they have devoured my extensive collection of blog posts and videos. I’m not alone; writers and artists have involuntarily become content suppliers. While Aretha Franklin’s chain of fools referred to betrayal of trust in love, writers feel betrayed by those who should be protecting our intellectual and creative property.

The term supply chain refers to the network of organizations involved in stages needed to deliver products or services. Typically, a product chain starts with raw materials that are sold to a manufacturer who creates widgets to wholesale to a distributor who sells the finished product to customers. Money is made at every step, and all benefit from their coordinated efforts. In today’s content supply chain, writings, artwork, music, and photography are the raw materials taken by Open AI, Meta, Google, and other AI firms. Our raw material is fragmented into bits and remixed with others’ stolen words or images to generate products these companies sell for profit. The content supply chain is unique because, those who are supplying the content did not intend to contribute to someone else’s product, did not agree to supply content, and were not paid.

That’s right, while AI companies are bringing in billions of dollars, creators of raw materials essential to their products are unpaid. As Ed Newton Rex, CEO of Fairly Trained observed, while AI companies need people, computing power, and data, they expect to pay for the first two and take the third — training data — for free. They argue that our content is simply used for “training”, and nothing is reproduced verbatim, but this is simply untrue. Verbatim responses are not uncommon, along with hallucinations such as fake references that use our names. Writers are pushing back, most recently with a Statement on AI training signed by over 30,000 writers and artists (including me.)

Aren’t there ways to protect original intellectual property from theft?

You might be wondering, why don’t copyright laws apply? The companies behind generative AI argue that “fair use,” a protocol that allows teachers to use copyrighted materials in the classroom, somehow applies to commercial companies with adequate assets to pay for content. As a professor I had to abide by strict university policies put into place to avoid copyright violations. For example, instead of simply sending a copy of an article to a student, I was required to give them a link so they could download the article through the proper channel: the university’s library subscription. Over a year ago the U.S. Copyright Office received over 10,000 comments in response to their request for input on the AI interpretation of fair use policies, but their Artificial Intelligence Study is still underway, with no new regulations in place to protect creators. While truly fair policymaking drags slowly along, and numerous lawsuits are mired in the court system, AI scraping proceeds unabated.

You might also wonder: why don’t Creative Commons (CC) licenses apply? This might seem like a logical solution. With the current licensing system, creators can indicate whether or not they agree to have their work remixed and repurposed. For example, someone who agrees to be a part of the content supply chain could use a CC BY license that “enables reusers to distribute, remix, adapt, and build upon the material in any medium or format, so long as attribution is given to the creator. The license allows for commercial use.” Of course, it is questionable whether the AI tool would actually acknowledge, let alone attribute the writer as the source. Creators who don’t want their work chewed up by AI could select the CC BY-NC-ND license that allows “reusers to copy and distribute the material in any medium or format in unadapted form only, for noncommercial purposes only, and only so long as attribution is given to the creator.”

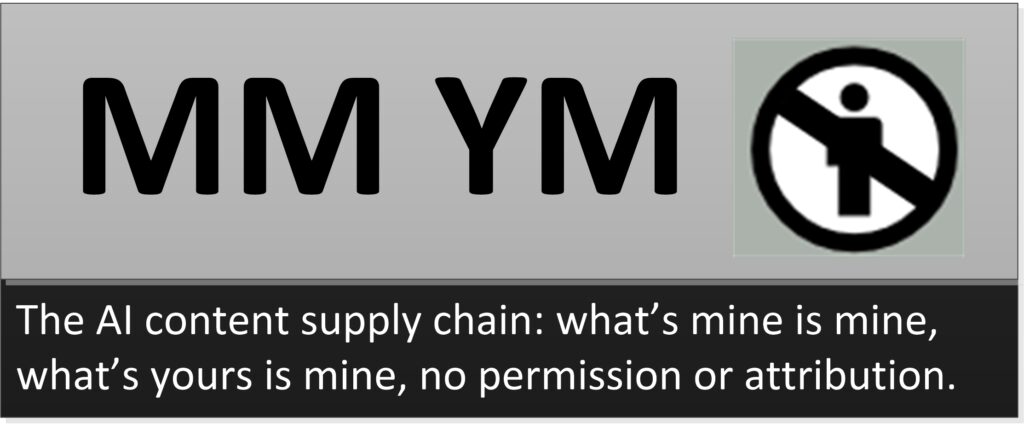

Instead, I imagine these companies assume they have their own “license,” MM YM: What’s mine is mine and what’s yours is mine, no attribution necessary. They implicitly say: “The billions of dollars venture capitalists invest are mine, and you don’t get any. What’s yours is mine because we say so, and we’ll keep information about our private theft. What’s yours is mine because we said so, and we’ll keep information about our theft private.”

Creative Commons is trying to address the AI content theft problem by adding “Preference signals” that “would empower creators to indicate the terms by which their work can or cannot be used for AI training.” They suggest that a CC solution has the advantage of allowing varied preferences such as “Don’t train,” “Train, but disclose that you trained on my content,” or even “Train, only if using renewable energy sources.” CC points out the need for this addition to the current license structure, because:

- The use of openly available content within generative AI models may not necessarily be consistent with creators’ intention in openly sharing, especially when that sharing took place before the public launch and proliferation of generative AI.

- With generative AI, a handful of powerful commercial players concentrated in a very small part of the world produce unanticipated uses of creator content on a global scale.

Preference signals, if respected by AI companies, would be a positive step. However, currently they are not legally enforceable, so creatives could not litigate cases where their preferences were ignored. Given that large commercial AI interests have disregarded copyright, it’s not clear why they would honor Creative Commons licensing.

Why does all this matter to scholarly writers and publishers?

For scholarly writers, the issues go beyond compensation. For us, the irreparable loss is to the integrity of our work. What we offer goes beyond ideas or opinions. Our writing is grounded in empirical research and cross-checked by knowledgeable editors and reviewers before publication. Scholarly books and articles aspire to a high standard in order to merit trust. Our thoughtful writing contrasts with the fragmentation of sources and unpredictable re-composition of results from large language models. There are good reasons outputs are known colloquially as AI slop.

In a scholarly article, we start by introducing a problem or question, defining the issues and contexts, and explaining why they are important. Then we offer foundations: who has studied this problem before and what did they learn? We discuss studies that adhere to basic ethical principles laid out in the Belmont Report: potential harms were minimized, participants were informed of risks, and they voluntarily consented to participate. We honor scholars by carefully citing and referencing them. Next, we lay out our own process, helping readers understand theoretical frameworks, ethical safeguards, methodologies, and methods. We discuss the results; what was learned, and what it means. A scholarly article is all of a logically flowing piece.

Years of academic study and research come to fruition in each scholarly article. Similarly, years of effort go into texts and academic books. We must do extensive research and careful thinking before we put words on the page. We work to develop a well-organized book, with sequential chapters, glossaries, and appendices that fit together. We navigate layers of oversight for the research itself and review protocols before the manuscript is accepted.

This kind of publishing involves little pay for writers in the form of book royalties and no pay for writing, reviewing, or editing journal articles. We do it because we believe in the power of new knowledge to help us understand our world and make it better.

You got me where you want me, I ain’t nothin’ but your fool

AI companies have got us where they want us: without transparency for sourcing, we are in the dark about what they’ve taken and what they did with it. If we can’t verify what was taken, how can we fight for any kind of remedy? Some academic publishers are trying the deal-with-the-devil approach by establishing licensing agreements that give AI companies access to their content. However, writers are not at the negotiating table. Publishers such as Taylor & Francisand Wiley did not inform writers or allow an opt-out of deals they made with AI companies. It is apparent that they signed deals without considering whether or how royalties would be determined. I learned in July that three of my books had been licensed to AI without my knowledge or consent. To date Taylor & Francis has still not adequately responded to my questions about how royalties for use of my books might be paid. The only comment I received was, “royalties will not be determined on usage or on any outputs in their AI tools.” If not output, then what? Inputs? Word count? In any case I haven’t seen a penny of the $10 million agreement Taylor & Francis made with AI companies.

Meanwhile, Microsoft and Google now argue that copyright should be waived so they can use anything they want without permission or compensation. If AI companies succeed in pushing governments to set aside copyright protections, even the licensing avenues will be lost. So, while we fight to defend the value of copyright and Creative Commons licenses and try to retain the integrity of our work, AI companies just keep singing:

One of these mornings

The chain is gonna break

But up until the day

I’m gonna take all I can take

Thanks to Don Covay for the “Chain of Fool” lyrics (1968) and to Aretha Franklin for her timeless interpretation!

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Supply Chain of Writing Fools"

It seems to me the Google Books case will favor the consumption of copyrighted work by chatbots, but what about CC-BY-NC content, that is offered freely, and often at an author’s expense, in exchange for not monetizing it? Wouldn’t AI engines consuming such content be in violation of such licenses?

As a biologist, AI researcher, author, and tool creator we have always adhered to and were strictly bound by copyright agreements. We as academics, have been stopped from reusing content that is not licensed appropriately to create tools that serve academics.

I am very concerned that large companies are trying to, and largely able to, flaunt these rules set for everyone else, especially authors whose work is being distributed without compensation and those of us who are trying to use these technologies in ethical ways.

We need rules to be put in place and enforced so that people who are creating content can control what happens to their content and those of us who use their content should not breach that covenant.

In your article, you wrote, “The companies behind generative AI argue that ‘fair use,’ a protocol that allows teachers to use copyrighted materials in the classroom, somehow applies to commercial companies with adequate assets to pay for content.” Fair use isn’t just a protocol; it’s encoded into U.S. copyright law (17 U.S.C. section 107, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/107), and it doesn’t govern classroom use of copyrighted materials (that’s 17 U.S.C. section 110, https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/110). Fair use balances the rights of creators to control their works with the rights of the public, allowing the latter to use copyrighted works without permission under certain circumstances to advance science and the arts. In addition, fair use applies to commercial, corporate entities in the U.S. in the same way that it applies to individuals.

I understand that many creators are outraged that their work is being licensed by their publishers to train AI, but the sole reason publishers can legally make these deals is that creators transferred their copyright to their publishers. If you want total control over your work, you can’t give up your copyright. It’s just that simple.

Good points, Jody, and I agree that writers now must consider retaining the copyright for their books. Of course AI companies are notorious for their disregard for copyright, so unless enforcement steps up, it is not much protection.

In my case, licensed books were originally contracted with a publisher that was acquired by by Routledge after suffering through the pandemic. Naturally, generative AI had not been released so I was not aware that I’d need to be worried about protecting my work. Times have changed, but that shouldn’t mean writers are disregarded.

There’s also the obverse problem that I don’t see discussed very much: the disposal of one’s online content with no warning or opportunities to retrieve said materials. I wrote about 120 detailed, scholarly articles on biotech for an online news magazine over a 10 year period. I referred people to my published articles all the time. I found out last year that the publisher was bought out, and the new owners just decided to dump all the old content. No notification given to anyone who wrote for said magazine. No archiving opportunity given. Pretty disgraceful behavior in my book.

The instability of platforms and online publications is problematic as you mentioned. I suggest that writers retain copies of everything and create your own archive!

I do have copies, but what I need to do is to post them on a substack or some place other people can access them online. It’s good that I kept copies, but that only helps me, not my readers.

Yes, good you kept copies! I started a Substack newsletter in August and have been pleased with the experience. My newsletter is “When the Field is Online” at http://tinyurl.com/qualnews. If you decide to post there please ping me.

I’d also note that I recently offered a webinar, and will have an informal online conversation this week, on the topic of curating your own work. In other words, revisiting and rethinking your published and unpublished work. See: https://tinyurl.com/mzmmac2r The recording is only available to members of the Textbook and Academic Authors Association, https://www.taaonline.net/join.

You can indicate whether you want to allow AI to train on your posts.

Rules and laws should and do apply— but ingestion for AI purposes is a new type of use and the question of whether or how fair use applies is essentially the question in the roughly 30 cases brought so far in the US against AI companies. One might also think that AI companies could determine what is CC BY content and what is CC NC content, although they might argue about whether they are NC or not. We shall see. But one of the points the author makes is that the “rule” in big Tech tends to be to go ahead and break things first, and then if they are forced to, make arrangements and settle things out– which often takes years. A helpful point in this debate is the EU AI Act with its requirement for transparency with respect to what content has been used for training purposes. Lots of details here still to be worked out, but at least then creators and authors will have some idea when their content is being used.

Thanks Mark. In the US, the Copyright Office asked for comments on “the use of copyrighted works to train AI models, the appropriate levels of transparency and disclosure with respect to the use of copyrighted works, and the legal status of AI-generated outputs.” They received over 10,000 comments! You can see them here: https://www.regulations.gov/docket/COLC-2023-0006/comments. Reading through them, you’ll see the the fair use question is hotly debated.

So far, they have published a report about digital replicas, but they haven’t ruled on fair use and transparency – so companies have taken advantage of the opportunity to take what they want. Writers, especially academic writers, don’t have a lot of say or clout.

As I tried to point out in this post, the input issues are only part of the problem. It is also concerning to have research-oriented writing taken out of context and mixed up with other garbage in to spit out AI slop.

I’d like it if the Copyright Office did venture a fair use opinion, but I suspect they will not, and will instead let the courts do the talking— that’s the way fair use jurisprudence works for the most part…

Court cases will be influential in the US, but the Copyright Office hasn’t given up the effort to define what is acceptable practice. Just last week Shira Perlmutter testified to the Senate:

https://www.copyright.gov/laws/hearings/Testimony-Register-Shira-Perlmutter-Nov-13-Hearing-Senate-IP-Subcommittee-of-US-Copyright-Office.pdf

Scientific publishers can also consider not selling copyrighted materials to big tech companies running AI engines for training purposes. As others note here, there’s an ethical issue here of not allowing the scientific record to be “polluted” by general LLM’s mashing that carefully constructed record up with all sorts of general Internet flotsam and jetsam. It should be noted that there has been a big push for open access and CC-BY and CC-0 licenses, often quietly supported financially by big tech companies, for a couple of decades now. However, I am afraid that if a publication has no copyright protection in the first place, there’s no way for an author or anyone else to assert copyright protections or author preferences ex-post facto, regardless of what the courts may decide in the future.