- “gift” by imago via Flickr

Can incentives motivate scientists to participate in social media?

Yesterday in the Kitchen, David Crotty (a trained scientist himself) proposed that publishers need to consider offering more incentives to scientists if they wish to seek their participation.

In his piece, Crotty gives several examples of stick and carrot incentives to encourage participation:

- a professor refusing to write letters of recommendation if students don’t use the lab’s social media’s website (a stick)

- paying science bloggers to write (carrot)

- sharing revenue with authors (carrot)

- providing open access article processing charge discounts to loyal authors (carrot)

The kind of incentives that David discusses are direct incentives — the kind of incentives that economists often talk about when attempting to motivate particular behavior. These direct incentives are easy to understand, and we find them everywhere: taxing soda reduces consumption; coupons and discounts encourage spending; employee stock options increases loyalty; etcetera, etcetera.

What is not acknowledged is that science is based on a strong indirect incentive called reputation. I call it an indirect incentive because reputation is an intangible reward. Reputation can be exchanged for a good job, a grant, an editorial position, but it isn’t worth anything itself. Reputation plus a small coffee at Starbucks still costs you $1.90.

Reputation is the coin that drives science and explains its publication system. In describing the sociology of science nearly 40 years ago, Warren O. Hagstrom in his seminal work The Scientific Community (Basic Books, 1965) summarizes the process of science in a single sentence:

The organization of science consists of an exchange of social recognition for information.

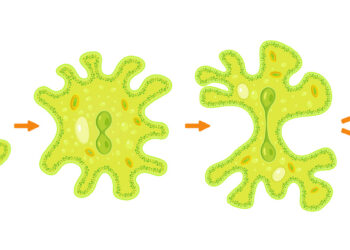

Unlike authors of fiction, who write to be compensated financially for their manuscripts, scientists gift their manuscripts to publishers — some even paying the publisher to take it — in return for the public dissemination of their work. Such gift-giving establishes the donor as a scientist, and the acknowledgment of that gift by qualified peers (through citation and other public forms of credit) builds reputation.

If we understand this reputation system, other processes in science make much more sense. It doesn’t matter whether it was Amazon, Sony, HP, or Apple that came out with the first e-book reader. But it does matter (a lot!) who was the first scientist to publish an important discovery. Disputes over priority can be fierce and pithy, pitting one group of supporters against another. Time-stamping the submission, review, and publication cycle helps reveal who came first. Even subject repositories like the arXiv date-stamp manuscripts and adhere to documenting the revision process down to the second. Coming in second doesn’t mean very much for science.

Recognition is a form of intellectual property. Since science puts a premium on originality and on advancing the field, there is intense pressure on being first. This is where the rewards are found. Those who are not acknowledged, his accomplishments are forgotten. — Robert K. Merton [1]

“Fine,” you say. “Science is based on a reputation system. Reputation still works as an incentive for desired behavior, whether it is indirect or not. Right?”

Right, but the indirect nature of reputation as an incentive insulates scientists from some of the blatant effects of direct compensation. Reward a doctor for every test that he prescribes and you are likely to get, well, the American healthcare system. Pay bankers for every CDO they build, and you shouldn’t be surprised at the risk these individuals take with other people’s money.

We are all driven by forms of direct compensation.

Yet, the indirect nature of the reputation system helps keep scientists insulated from inappropriate behavior. Reputation is cumulative. It takes years to build a portfolio of publications, grants, and awards. But reputation is also fragile — get caught publishing fraudulent data, for example, and you can kiss your entire career goodbye. The permanency of the publication record ensures that bad acts are kept in the minds of one’s peers.

So while I agree with David that publishers need to consider incentives if they wish to motivate scientists to participate in new ventures, I’m leery that providing direct compensation is the way to go. It’s just too tempting.

Unlike executive compensation, there is no golden parachute in science.

—

[1] Merton, R. K. 1957. Priorities in scientific discovery: a chapter in the sociology of science. American Sociological Review 22: 635-659.

Discussion

13 Thoughts on "The Stick and the Carrot: Why Direct Incentives in Science are Dangerous"

Isn’t there a further motivation behind reputation? Doesn’t better reputation lead to a better job with a higher salary? Doesn’t it help bring in better funding to a lab, to hire more people and to buy better equipment? While we’d like to think that science is a noble (or nobel) pursuit, pure and above everyday concerns, scientists are just like everyone else on the planet–they gotta eat. Scientists need to feed their families, pay their employees, put a roof over their heads.

Scientists do all sorts of things solely for financial compensation. They write grants, they give talks and write book chapters for honoraria, they write or edit whole books for royalties, they serve as consultants for companies for payment. You’ll note that the Nobel Prize and MacArthur Awards have big checks that accompany the lovely medallions and certificates.

One of the common complaints about science publishing (and social media for that matter) is that it’s exploitative, that the scientist (or social network member) does all the work and the publisher (or network owner) takes all the profit from that work. One solution has been to try to set up a system that removes this imbalance by taking away the profits a publisher sees from subscriptions via an author-pays model. It’s not yet perfect, as the publishers behind them are instead profiting from the author fees, but presumably it would evolve to a point where the fees are reduced to a break-even level.

I’m suggesting an alternative way to make things balanced, paying the author for their hard work, sharing in the profits driven by their efforts. This wouldn’t result in any decrease in the rigor used to evaluate a publication. As we’re all aware, scientists are under extreme pressure to publish papers already (again,their salaries depend on it). I don’t think further compensation would increase this pressure enough to matter.

But even if we decide that it’s a bad idea for journals, what about ancillary activities. Most of the examples I used, writing a blog, writing up a method, rating or commenting on a paper don’t provide the reputation reward one gets from a data paper. As noted above, scientists do all sorts of things for direct compensation. Should we all think it’s fair that we’re expected to do tons of extra work so some MBA’s running a startup can get rich?

David,

I think we’re mostly in agreement here but my point is a little more nuanced than your representation of it.

Scientists are motivated by incentives just like everyone else. My argument is that the indirect nature of academic reward (incentives working indirectly through a construct called “prestige”) provides an insulating layer that prevents widespread personal corruption that would be more prevelent under a direct compensation model.

I agree that the language can obscure the economic model: an “honorarium” could be described as a “bonus” in the business world. But the language underscores the values in the academy. The main payout of a major award is not the cash but the prestige that comes along with it. That prestige, as I described, can be later traded for real material things like a good job or resources.

In sum, publishers should be looking at forms of indirect payment that feed into the value system of science and not forms of direct payment that feed into the value system of corporate culture.

The reason the reputation reward works though, even if it is couched in obscuring terms and separated by a few layers of insulation, is because it is at some point linked to real-world rewards, namely funding and security. An associate recently published several superb papers, which helped her land 3 big grants, which brought in a job offer from a competing university, which she used to renegotiate her deal at her current location, raising her salary and moving her lab to a newly renovated space. While she does enjoy the extra prestige the papers bought, she probably gets more pleasure out of having a better funded lab with better equipment and more money to support talented postdocs, students and technicians (not to mention the pleasure she gets from the view from her new office window or from her new car).

And that’s why there’s no buy-in for social media. Despite the best sales jobs that have been offered, there’s no direct or even indirect tie between the reputation one gathers from participating and any real-world benefit. PLoS is trying to sell article commenting as if such a link existed:

“People who comment frequently and write valuable comments will build reputations over time. If you rate, annotate and comment on PLoS ONE papers now, you will be one of the early adopters and will be recognized and respected for this in the future.”

Despite this wishful thinking, the scientific community in general doesn’t seem to agree, and instead appears to be focusing their time and energy on the activities that build the types of reputation that is indeed tied to actual reward. And that’s the big problem for social media in science. There’s no motivation for participation. You can’t just declare something important without it actually having any useful impact. I noted in my article that it’s unlikely that we’ll see funding agencies or tenure committees offering up their very valuable real-world rewards as compensation for commenting on the works of others.

So if the current system is not available, what other rewards can be offered?

David,

Your PLoS ONE example is a good one. Obviously, they have not built in enough carrots into their reputation/reward system. But others have.

Letters to the Editor of major medical scientific and medical journals function as much to draw attention to the commenter’s own work through self-citation. Sort of like, “that was interesting, but did you know that I’ve done similar work?” These letters to the editor are indexed by ISI and therefore boost one’s citation count. Little work for a few extra carrots.

I would suggest that the majority of social media endeavors for scientists haven’t built in enough carrots, or really any carrots at all.

And a detailed, well-thought out and meaningful letter to the editor probably does deserve more credit than clicking on a star rating, or adding the comment, “nice work” to someone’s paper. Not sure if ISI would be interested in indexing those….

Every research scientist gets paid so direct compensation per se is not an issue. But writing an invited book chapter, making an invited presentation, or getting an award are all evidence of achievement. The funders want to see that, as it demonstrates the wisdom of their funding choices, which they often have to defend.

The problem with social media is precisely what the advocates like most, namely anybody can do it. If you can tie the social media compensation to evidence of scientific achievement then it might work. Otherwise is is moonlighting. Consulting often carries the same stigma by the way.

This gets back to the issue of whether science can really be egalitarian, or if we’re better served if it remains a meritocracy. To me that’s a major problem with social media, that they select for consensus and popularity, rather than quality (more on this to come, I promise).

I have no idea what egalitarian means in this context. Do you mean researchers get funded by popular vote, or a lottery, or some such? The whole point of merit is to decide who gets funded to work on which problems. Note by the way that the problems are just as important as the people. Should problem selection also be egalitarian?

I was referring to your comment here as far as those hoping for an egalitarian approach:

Some embrace social media on ideological grounds, as a new form of egalitarianism. To them science is simply organized wrong, so looking at how science works today is irrelevant. The culture is corrupt and must change.

As you note, such approaches are not compatible with science. I worry that much of it is an attempt to substitute the ability to network instead of using actual achievement as the measuring stick of status, funding, etc.

I am reminded of David’s remark yesterday that we require accurate appraisals of what our users need and value most. This is the basis for every successful development project.

In the context of this conversation, we will learn best by isolating the specific motivating factors that inspire action by various classes of contributors.

Phil’s mention that scientists have paid publishers to disseminate their work stands out for me. We have experienced a paradigm shift, wherein the packaging and dissemination of research by a third party (publisher) is less incentivizing than it was in the past. There are simply many more venues and routes to readership (not disputing the fact that some have more clout than others). In bullets:

– Having the ability to package and disseminate information has lost value (-)

– Brand alliances that provide a shortcut to a targeted readership have more value, due to the amount of noise in the information space (+)

– Being first-to-market/trailblazing is still of high value and worth jockeying for(+)

What this boils down to is a question of IMPACT. The playing field for information exchange is transformed. What researchers and scientific organizations seek are instructions for play that help them maximize the impact of their research, voice, and notoriety in this changed environment–which, in turn, secures their seat at the table and assures their survival.

Well said. I probably tend to take things to the next step though, to think in more practical terms about what purpose “IMPACT” really serves. Obviously there’s a big ego boost, but that’s not the sole reason why it’s so valued.

I don’t think any analysis can avoid looking at the job market, and how crowded and competitive things have gotten. At the recent NAS EJournal Summit, one of the scientists noted that for every job offered at his institution, they get at least 400-500 applications. This scientist was a postdoc at one of the UC’s before his current job, and noted that of the 3,000 postdocs employed at that particular university, he was among the 5 or 6 who got high profile jobs that year.

It’s a brutal time to be on the job market and because of this, the scientists who are going to succeed and thrive are those who are tightly focused on doing the things that lead to jobs. And that’s certainly one place where impact comes in–does the activity directly help my job prospects. For those already employed, does this help my funding, my tenure, advancement (or the funding/job prospects/advancement of my students and postdocs)?

It’s easy to get lost in the lofty ideas about information exchange and the higher purposes of science, but it’s always important to remember that, as I put in my first comment above, “people gotta eat”, and that’s always going to come first.

Forget social media or a royalty for an article – I could care less. Give me a paper in Nature or Science???, now THAT’S motivating!

![Reblog this post [with Zemanta]](http://img.zemanta.com/reblog_e.png?x-id=0a2b7a85-cda8-4b52-aa0b-8f075adf3b58)