In recent years, open access has moved beyond a core of faculty and librarian activists to achieve acceptance, if not always a full embrace, broadly across many libraries and publishers alike. Many publishers have open access models of their own, and academic libraries are building offices of scholarly communication and taking on formal publishing responsibilities in some cases as well. Many academic libraries today invest in scholarly communication – which typically includes, at a minimum, efforts to support and reform the dissemination of research. These scholarly communications investments are designed to pursue an array of objectives and to serve a variety of roles.

This array of objectives and roles is a key finding of a recent study of the scholarly communications organizational structure, objectives, and programs of a nearly a dozen major research libraries. Working with Sarah Thomas of The Harvard Library, my Ithaka S+R colleague Deanna Marcum and I studied a group of the most research intensive peer institutions, mostly in the United States, to understand how their offices of scholarly communications have developed in recent years. Our study, released last month, is available on the Ithaka S+R website.

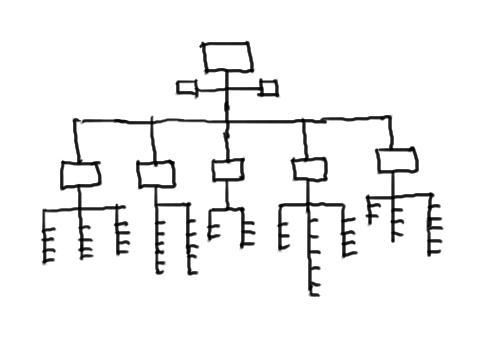

We found a wide array of models for organizing and implementing scholarly communications programs at major research universities, which we grouped into four categories:

- Collections-based: Scholarly communication functions are carried out to advance a strategic objective of transitioning the library’s collecting activities away from licensing content and towards supporting open access to scholarship. Libraries adopting these models are situated on campuses with an open access policy. These models treat open access as another type of publishing that the library supports with its collections resources and one that it would thereby advance.

- Research-based: Scholarly communication functions are aimed primarily at supporting researchers on the campus, to ensure that they have access to the newest formats and channels for releasing their scholarship and helping it to have the widest distribution and greatest impact. Libraries that adopt these models do not have campus open access policies in place, but there is nevertheless an objective to contribute to progress in scholarly communication.

- Collective Ownership: Scholarly communications functions are viewed as the responsibility of the entire library organization, with essentially every department and unit expected to integrate these issues and priorities into their work. There is no “central office” ultimately responsible for organizing or managing scholarly communications activities.

- Not an institutional priority: The library has not identified scholarly communication functions, per se, as a high-level priority and has not assigned staff responsibility for them. This may be the case because the university’s academic leadership or governance structure has not been able to prioritize open access.

The variety of objectives that academic libraries have for scholarly communications is to some degree a reflection of the different levels of engagement and prioritization that their parent universities have on these issues. As libraries continue to develop in this area, and a variety of partnerships such as the Digital Commons Network, SPARC, SHARE, and even publisher APIs develop to engage with and support these efforts, they do so in the context of real diversity of objectives, functions, and responsibilities inside the offices of scholarly communications themselves.

Discussion

1 Thought on "The Objectives and Organization of Scholarly Communications Functions in Research Libraries"