Just a short post today to highlight an interesting new initiative in the field of manuscript exchange (the process of taking an article that has been submitted to one journal, and transferring it for submission to another journal, most commonly after it has been rejected by the initial journal). This is an area that, if not exactly “ripe for disruption” (an overused and ill-applied phrase) could certainly do with some streamlining. Researchers commonly complain about the time and effort involved in reformatting an article for re-submission to a new journal after rejection by their first choice (Steven Inchcoombe described it as “publishing’s nasty secret” at the UKSG One-Day Conference last November). And while, in theory, therefore, the now relatively common concept of transfer within a publisher’s portfolio ought to be popular, it is often greeted with cynicism (particularly in scenarios where the transfer is from a prestigious subscription-based journal to a less established open access journal; it does reek a little of “your article’s not really good enough for us, but we’ll publish anything if you pay us”).

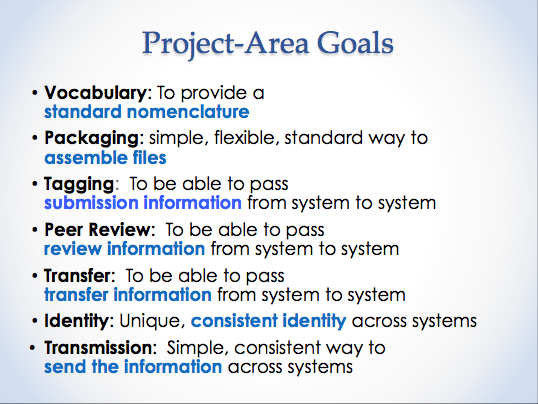

So a movement to simplify transfer across publishers is a welcome sign of the publishing industry overcoming competitive boundaries to make life easier for authors. MECA, “Manuscript Exchange Common Approach“, was launched I think at this year’s SSP Annual Meeting and presented again by HighWire’s John Sack at last week’s ISMTE conference (the International Society of Managing and Technical Editors — a wonderfully collegial and practical group if you’re in that kind of role and looking for peer discussion, networking and professional development). To quote the MECA website, “a group of manuscript-management suppliers has taken up this challenge [of transferring manuscripts and peer review data across publishers and systems] and is working to develop a common approach that can be adopted across the industry”.

Participating organizations (and systems) include Clarivate Analytics (ScholarOne), Aries Systems (Editorial Manager), eJournal Press (eJPress), HighWire (BenchPress) and PLOS (Aperta). The focus is on defining recommended best practices in the following project areas (slide from John’s talk at ISMTE, which I don’t think was video recorded, but you can see a video of a slightly earlier iteration of the talk on the MECA site):

This focus on “recommended best practices” reminds me of what we set out to do at KBART (Knowledge Bases And Related Tools, a UKSG- and NISO-led project which defined some basic formats for exchange of title level metadata / holdings data between publishers and library software suppliers). That project is now over ten years old, and its recommended practices have been widely adopted, which provides an encouraging precedent for MECA in terms of gaining adherence to voluntary principles. That said, KBART was “voluntary” in what I imagine Joe Esposito might call “the Sicilian sense”; it quickly became part of library RFPs and therefore publishers and systems suppliers were pretty soon over a barrel to comply. Whether authors have sufficient power to drive MECA’s uptake in the same way remains to be seen. And of course, whether authors actually want to transfer reviews (in particular) between publishers is also an open question. This is not the first experiment with review transfer across publishers; the Neuroscience Peer Review Consortium was launched in 2008 as a framework for sharing of reviews between publishers, and the progress / fate of portable peer review initiatives such as Axios, Rubriq and Peerage of Science have been widely covered here in the Kitchen. These experiments haven’t always met with success — uptake is limited, perhaps because authors don’t necessarily want a journal to know it was not their first choice. And it’s interesting that the MECA initiative is primarily being led by systems suppliers rather than publishers; how would (say) a small publisher feel about putting time and effort into the peer review process for a paper, and then passing the results of that process to (say) a bigger competitor? It’s hard to model who has most to gain from manuscript exchange, and it may be another scenario in which small publishers end up losing ground to bigger ones.

What the MECA team have not yet mentioned, as far as I know, is anything about introducing standards to simplify formatting across different journals. That’s the bit that really pains researchers, and seems utterly ridiculous in this day and age (where digital publishing offers so many better ways to impose a journal’s “personality”, and really what else are arcane formats trying to achieve?). Every time it comes up, publishers tell me woefully that their editors will defend to the end the need for their journal’s own specific format — though that hasn’t prevented some experimentation with post-publication formatting, as with Elsevier’s “your paper, your way” initiative. If MECA takes us one step closer to doing away with journal-specific formatting requirements, that will certainly be welcomed by authors.

- Learn more about MECA in a webinar on September 20th–sign up via the project’s homepage.

Discussion

11 Thoughts on "MECA – A New Manuscript Exchange initiative"

Agreed that it isn’t really “ripe for disruption” – though I do wonder if is “ripe for lock-in”? See https://lisahinchliffe.com/2017/02/06/elsevier-predictions/

Great post, Lisa – thanks for sharing it here. I think you are right that many missed the point of Elsevier’s patent application, and that we are looking at a potential “clearing house” for all submissions across all publishers.

I fear that MECA is providing a solution by conflating two separate issues. From their website:

Authors lose time and effort when their manuscript is rejected by a journal and they have to repeat the submission process in subsequent journals. Plus, it is estimated that 15 million hours of researcher time is wasted each year repeating reviews.

While I have no qualms about finding a technical standard solution that would enable manuscript transfer, the second part of MECA’s justification is based on an oft-repeated, but ill-supported, claim that re-reviewing a manuscript is a complete waste of time.

Reviews are inherently subjective and reviewers are often biased. Getting a second or third pair of eyes to review a manuscript is beneficial to the evaluation of a manuscript. It is not simply a redundant and wasteful process.

So, please. If MECA is attempting to justify why standards are important, make it based on transfer-alone, and stop promulgating a distorted view of the value of peer review.

In connection with this, any two journals will differ in their exact scope and coverage. An additional layer of review is therefore entirely justified on the basis of relevance to the second journal.

As far as smaller journals sharing reviews with larger journals, my understanding of MECA (from attending the SSP presentation) is that journals and authors set the rules for transfer. So a smaller journal can decide whether to share reviews with a larger journal in the transfer chain (and if not, then they would share only the manuscript submission metadata). If an author sees sharing reviews with the next journal as a benefit, then I would think that would make submitting to that smaller journal more attractive because the author would know that, even if rejected, the journal is trying to help expedite a positive decision elsewhere.

Thanks, Todd! That’s a helpful clarification.

A small piece of this is the standardization of references in a way to be transferable and not dependent on a specific reference management software. More specially, can healthcare journals move away from an insistence on Vancouver formatting of references with numbered, inline citations? This insistence hinders collaborative writing on platforms such as Google Drive. PeerJ has eliminated this for their healthcare jnls and uses the MLA. With MLA and inline (author, year) format reference software is not needed at all. If MECA addresses this, authors writing in collaborations can celebrate. If DOIs or PMIDs are encouraged, seems publishers would benefit.

Good question, Bob. I just experienced this need firsthand after I completed my first scholarly book chapter on Google Docs and then converted my handful of references to APA style manually.

It looks like there may be at least one Google Docs plug-in, EasyBib (http://www.easybib.com/), which purports to let authors create inline references and then converts them to any one of about 7,000 reference formats, including several variations of Vancouver style. EasyBib has an average rating of 3.86, from 3,694 reviews currently. So this one may have been solved. Has anyone out there used EasyBib with good results?

I may be obtuse, but I don’t understand why it makes any difference what format is used for a manuscript being submitted to a journal, anymore than it does a book manuscript submitted to a book publisher. How is peer review affected by format? Conforming to a style guide of course makes sense after acceptance, but I fail to see why such standardization should apply before acceptance.

If our goal is easy transfer of manuscripts across publishers in order to help authors, seems publishers should accept, at the time of manuscript submission, a common format for all elements including references. Currently, resubmitting articles to a second publisher can be vexing work for an author unless the author uses reference management software. As an author, I feel like I am being forced to use reference management software and thus unable to use collaborative writing methods.

I am late to the comments here as I catch up from being on vacation (shhh, it’s true that I did not read TSK while on vacation). I have been trying to make the argument that streamlining the submission and format process is a no brainer for publisher collaboration. Many publishers are already removing format requirements for the initial submission (though references numbered vs in line is a beast of an issue). At ASCE, we have been passing through subs with very, very few format requirements for years. That all said, as more and more publishers ditch requirements, how far off are we really in what’s acceptable?

Differences in the fields may persist but mostly papers stay in their own areas and don’t jump from say a bio journal to an engineering journal. Streamlining the formats also opens doors for more third party online collaborative authoring tools. Now they have multiple format outputs and I really don’t know how easy it is to switch from one to another.

I agree with the comments that there are questions about the usefulness of making the reviewer reports portable. If your reviewers are not just looking at the content/science/methods/etc/, but are also making a judgement on whether the paper fits a journal, re-using reviews is of limited usefulness.