We talk about the future of publishing quite a bit on the Kitchen, as though we can picture it with greater clarity than the world actually swirling around us today. The past, however, is often neglected except when invoked nostalgically, as in “before the commercial giants took publishing away from us.” I have found that publishing’s past can provide some useful lessons, if only for forensic analysis, as we ponder what has changed, what has not, and how much of the changes are due to forces outside of publishing itself.

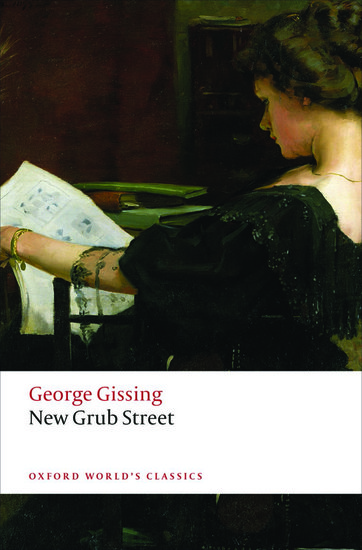

It was thus with great pleasure that I just read George Gissing’s fine novel New Grub Street (1891), a minor classic that depicts the state of the publishing industry, and the poor, often truly impoverished, people who labored in it in London in the late Victorian period. The title is a reference to the metonym for commercial publishing, as we might today use “Wall Street” to refer to the financial industry, wherever a company is located, or “Silicon Valley” to refer to technology and semiconductors, even though they are mostly manufactured in Taiwan. Besides its many merits as a literary work, New Grub Street provides us with fine detail of the process of writing books and for “magazines” — a term that in context refers to every kind of periodical publication, with the emphasis on so-called journals of opinion, which today would include such publications as Commentary, The National Review, Jacobin, The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic, Harper’s, N+1, maybe even The Scholarly Kitchen and countless other Web sites.

It was thus with great pleasure that I just read George Gissing’s fine novel New Grub Street (1891), a minor classic that depicts the state of the publishing industry, and the poor, often truly impoverished, people who labored in it in London in the late Victorian period. The title is a reference to the metonym for commercial publishing, as we might today use “Wall Street” to refer to the financial industry, wherever a company is located, or “Silicon Valley” to refer to technology and semiconductors, even though they are mostly manufactured in Taiwan. Besides its many merits as a literary work, New Grub Street provides us with fine detail of the process of writing books and for “magazines” — a term that in context refers to every kind of periodical publication, with the emphasis on so-called journals of opinion, which today would include such publications as Commentary, The National Review, Jacobin, The New York Review of Books, The Atlantic, Harper’s, N+1, maybe even The Scholarly Kitchen and countless other Web sites.

It’s the detail that matters. We learn for example, how much the author of a novel is likely to get paid, and whether the payment is a flat sum or includes a royalty; apparently only the more successful authors ever received a royalty. We get authoritative guidance on the productivity of writers (how many pages a day, how many books a year), the income of editors, and the different economic implications of writing a one-volume novel or the more profitable three-volume variety, the mainstay of the commercial lending libraries, especially Mudie’s, which was the Amazon of its time. We hear quite a bit about rivalries and literary feuds (one of the industry’s universal themes), but also about how book reviews could simply be disguised press releases. For example, the protagonist, Jasper Milvain, writes, and is paid for, three separate, adjulatory reviews of a friend’s hopelessly uncommercial novel. He writes these anonymously, and his sister notes with wonder and admiration that no one would guess that they were by the same person.

A particularly amusing, if bitingly cynical, passage takes place late in the book, where several characters debate the viability of a proposal to revamp an existing publication into one for ‘the quarter-educated.” Yes, they really use that term, with snarling irony and pomposity. I was reminded of a conversation I had during the Pleistocene period with an extremely successful book editor, who was my colleague at Random House; she had, in the jargon of the time, “hot hands.” I asked her how she did it. She looked for manuscripts for people who don’t read books, she said, because the people who do read books read these, too. I must remember to hide my copies of the novels of Robert Harris.

New Grub Street is not just about the plumbing of publishing; it also surveys the thinking of the time about the emergence of the “realist” aesthetic in literature. ‘Realist” in this context refers to a set of literary conventions or artifices that aim to provide an almost journalistic approach to works of the imagination. Gissing was a realist, but he notes the limitations of this outlook in the character of Harold Biffen, whose commitment to realism cannot stop him from falling hopelessly in love with the magnificent, unattainable Amy Reardon. Biffen commits suicide, and Amy mourns his loss, though perhaps feeling a bit of pride in having evoked it. A good realist knows that romance and fantasy are part of realism.

So what has changed? The centrality of publishing, and of the book in particular, for one. It is hard to imagine what it must have been like in the media world before there was media — before Edison gave us recorded music and the motion picture; and Tim Berners-Lee was still a century away. Also very different are the economics of publishing and its participants, though this has little to do with publishing and much to do with the overall growth of the economy. Gissing’s Biffen may have had to pawn his coat in order to buy a slice of bread, but today’s Biffens are more likely to serve as adjunct instructors teaching creative writing at community colleges. Today the phrase “starving artist” is mostly a metaphor.

What hasn’t changed is the hope of making a killing. There is in the publishing genus a wild, against-all-odds prayer for transformative success. This could take the form of the liberally cited article, the serial publication that carves out an audience just as a new field is emerging, or the dream of a prominent place on The New York Times’s bestseller list. This is because hope springs eternal in the human breast, a phrase coined by Alexander Pope in 1732. I wrote another Kitchen post on the representation of publishing in fiction (William Dean Howells’s A Hazard of New Fortunes) a few years ago, which is explicitly about striking it rich. Gissing’s novel is the better book, but Howells’s is more prescient: the arguments in that book are still taking place today, though they may have moved a few miles east from Manhattan to Brooklyn.

Should you read New Grub Street? Yes, if you want to learn more about the history of publishing. I would add that the book is insightful, at times painfully so, about the nature of English urban poverty, the class system, and the place of women in British society. (Gissing also wrote The Odd Women, which centers on women seeking to enter the commercial world in order to become financially independent. The means to achieve this is to master that revolutionary technology, the typewriter.)

To recommend New Grub Street as a purely literary experience, well, it depends. If you read only a couple novels a year, and don’t naturally lean toward the English Victorians, this probably should not be near the top of your list. But if you have already tasted Dickens and George Eliot and the supporting cast of the Brontes, Thackeray, Elizabeth Gaskell, Trollope, and other prominent Victorians, Gissing may be worth a look. He lacks the brio of Dickens and the granite intellect of Eliot, but his unflinching portrait of English society has the virtue of feeling incontrovertible and makes it very much of our time as well as of his.