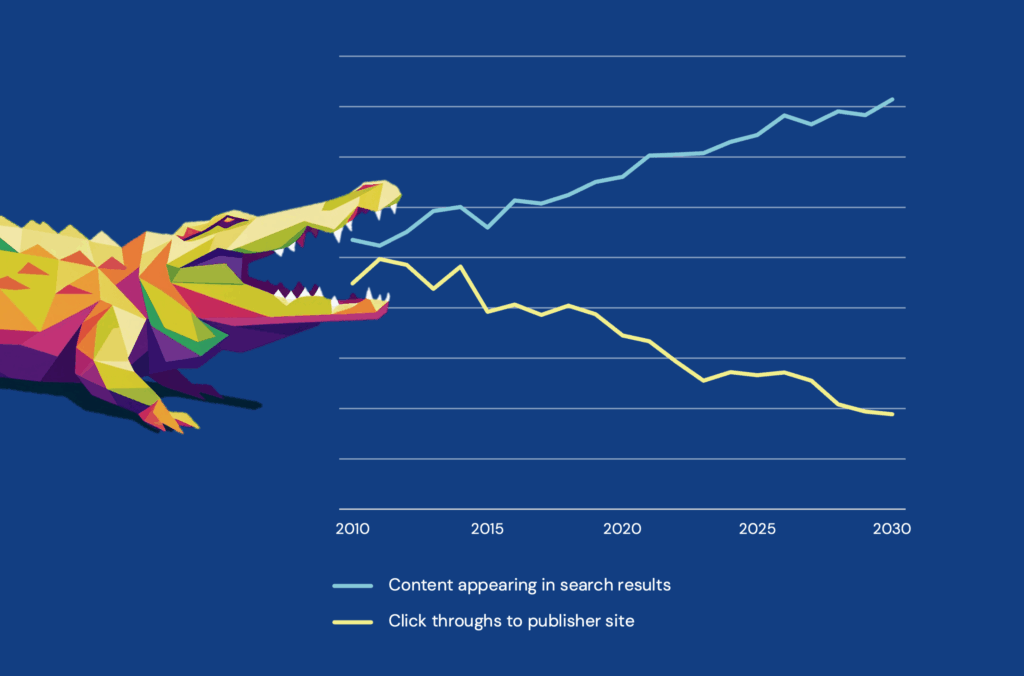

Open wide and say “aaargh”: we’re going to talk about the Crocodile Effect. You’ve probably heard of it already, even if you don’t recognize the term. It is the biggest threat currently faced by scholarly publishers, and yes, I know that’s an audacious claim given the research funding crisis, peer review crisis, research integrity crisis, and all the other crises of the day. Yes, I’m talking about “Google Zero,” “zero-click search,” “On-SERP fulfillment,” “walled-garden search,” or the many other terms that are bandied about to describe users getting answers directly from search engine results pages (SERPs), rather than clicking through to source sites such as journal articles.

The term “Crocodile Effect” derives from a LinkedIn post by SaaS marketing expert Tim Soulo: “The past 12 months of GSC [Google Search Console] data for the Ahrefs Blog [his website] look like a crocodile. And I’m pretty sure you’re seeing the same crocodile in your own GSC.” That is to say, the Crocodile Effect is the gap between impressions of your content in search engines, and click throughs to the full text on your platform.

Eating our traffic

The Crocodile Effect has grown hugely since the addition of AI-generated knowledge panels on search pages (discussed by Stephanie in a post in December) and is the central USP of new “AI web browsers” like Perplexity, or OpenAI’s Atlas. Publisher search results are pushed down the page, and although they may appear in the side bar offered alongside knowledge panels, they may be shown further down the list than more answer-oriented or news-driven content. Content impressions continue to rise because the content is being ‘shown’ — but fewer users click through to the full text on your website, creating a threat to any organization whose business model relies in usage as a metric of customer success. This includes scholarly publishers — whether the customer is an institution paying for a subscription and expecting to see lots of downloads by their users, or an author paying an APC and expecting to see lots of reads. Fewer site visits puts revenue at risk by weakening publishers’ renewal negotiations or reducing author retention. Low traffic is also likely to reduce citations and brand awareness, undermining publishers’ vital role and reputation. Publishers have spoken at conferences about the drop-off they’re seeing (OUP’s John Campbell told last year’s London Book Fair that he attributed a 19% drop in click-throughs to their academic reference content to zero-click search; one October 2025 study shows that over half of Google searches now end without users leaving the search engine results page 😱. As Dariusz Jemielniak puts it in his recent Nature article (thanks James Butcher at Journalology for drawing my attention to it, and for this excerpt), “When AI chatbots provide seemingly authoritative responses drawn from Wikipedia’s very pages, why would anyone navigate to the source, let alone contribute to it?

Threatening research integrity and transparency

Zero-click search is not only a threat to web traffic. It is a challenge to research integrity and transparency. Zero-click search amplifies and camouflages misinformation — by reformatting content, it removes the contextual cues that would otherwise help users make both conscious and subconscious choices about which content to trust. AI panels are well-articulated, seemingly polished and credible, but generated from a problematic mixture of sources. They contaminate trustworthy peer-reviewed content with poorer quality research, misinformation (inaccurate content, e.g., with missing caveats or distorted interpretation) and disinformation (content deliberately manipulated or invented to mislead).

Citations in AI panels are deliberately given low prominence — and reduced to a single symbol, stripped of quality indicators such as journal title or peer-review status. If users request a reference list for AI-generated summaries, the AI cannot reliably provide one, because it generates content dynamically without persistent tracking of exact sources, meaning citations may be missing, incomplete, or fabricated. The absence of clear attribution increases the risk of mis-citation or even citation of the AI tool itself rather than the underlying article. This lack of transparency renders panels unreliable and threatens research integrity.

Understanding and addressing zero-click therefore helps publishers not only protect and retain usage, but also safeguards the accuracy, trust, and integrity of the scholarly record — ensuring that authoritative sources remain central in a landscape increasingly vulnerable to misinformation.

The Crocodile Effect is exacerbating the risk of publishers being swallowed — simultaneously losing control of discovery, and losing visibility, authority, and revenue.

Zero-click search strips away credibility and context, making it harder to demonstrate the value of publishers in the process of scholarly communication. Publishers are at greater than ever risk of being reduced to invisible suppliers rather than valued partners. AI developers may depend on the corpus of authoritative information managed by publishers, but as parasites at risk of killing the host. The pathway to a more symbiotic relationship needs to be forged by publishers.

What can we do?

The scholarly sector needs to act quickly to steer the next stages of this seismic shift in how information is discovered and consumed, and how emerging usage behaviours are measured, reported and valued. This might mean:

- Developing new Codes of Practice for collating and reporting off-site usage

- Working to reshape institutions’ and authors’ perceptions of “what counts”

- Redefining what Fair Use means and creating licensing or royalty frameworks for derivative content

- Setting standards for how peer-reviewed content is indexed, ranked, referenced and attributed by AI tools

- Testing new tactics and features for attracting, retaining and maximizing usage

- Accelerating Answer-Engine Optimization (AEO) or Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) work.

What is clear is that this issue affects all departments (technical, editorial, marketing) and all types of organization (publishers, platforms, but also libraries and institutions, societies, conferences). No one department should be trying to tackle this alone, and many of the issues will need cross-publisher collaboration through the auspices of organizations like SSP, STM, NISO, COUNTER, ALPSP, and others. In the immediate term, I’m devoting my next quarter to a fast-track research project to dig beyond the metrics into user behaviors (is the traffic we are losing ‘quality’ or ‘quantity’; in what scenarios do users still choose to click through to source material; do users understand which content is generated on the fly by AI, and how — if at all — do they gauge the credibility of such content), identifying AEO quick wins from our sector and beyond (what are mainstream media or FMCG retailers doing? what kinds of metadata or ‘interstitial’ content correlates to higher ranking in AI summaries’ reference lists? what kinds of UX / features help increase time on site / page views from visitors who’ve arrived via AI panels — and so on.) (Do contact me if you would be interested in learning more about this project — I have a few sponsor places left for interested publishers / platforms.)

Ultimately, the Crocodile Effect is just the latest front in a battle that’s been underway for some time — how knowledge is mediated, and by whom. But it is a scaling up of hostilities, threatening not just the status quo for scholarly publishing business models, but the fundamentals of trust and attribution. Understanding what *exactly* is happening (beyond the data) is critical to understanding what we need to do — and whether we have the influence to do it.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "Responding to the Threat of Zero-Click Search and AI Summaries: How Do We Tame The Crocodile?"

Great initiative!

Like it or not, it seems that AI Chatbots offer a superior (or at least preferred) method for users to interact with scholarly content. Other than one or two large publishers, journals will be systematically disintermediated by these services.

No point in crying over spilled milk. We’ll have to adapt. Part of this adaptation should include developing extremely robust licensing and legal strategies to gain leverage in future negotiations with AI channels.

Thanks, Richard – yes, I think that’s the key point. We need to adapt, both in terms of the format of the content we publish, and in terms of how we license it. There are parallels to what happened with ResearchGate about 10 years ago. I remember speaking on a panel at APE and saying “we have to accept that users will do what works for them – and find ways to adapt to / accommodate that”. (And getting very short shrift from others on the panel, but a few years later that’s exactly what was happening with big publishers’ agreements with RG. The question is whether we as a sector have the same leverage / agency with LLMs / AIs as we did with RG!)

“Like it or not, it seems that AI Chatbots offer a superior (or at least preferred) method for users to interact with scholarly content.”

I suppose you are representing publishers. I suppose because no one in my field prefers these for “interacting with scholarly content”. In fact, a big uproar occurred when ACM decided to go with the hype bandwagon (see, e.g., https://anil.recoil.org/notes/acm-ai-recs). Even heavier criticism has been expressed in other fields (see, e.g., https://irisvanrooijcogsci.com/2025/08/12/ai-slop-and-the-destruction-of-knowledge/). But as for the article’s topic itself, it is indeed a major issue affecting also news media, and, I again suppose, the whole open web.

You’re on record as the “not” part of “like it or not”!

The benefits of AI are certainly more questionable when it comes to content generation.

However, most of the academics I know have become avid users of Chatbots for researching, ideation and discovery. That’s anecdotal and why we need Charlie’s initiative to gather empirical data about the impact of AI on usage.

I am not technical but I was able to use an LLM to “vibe code” modifications to my Chrome browser right-click context menu so I can skip Google search and instead search websites I actually want results from: Pubmed, MedlinePlus, ORCID, Chicago Public Library, Wikipedia. I was surprised how easy it was to do this. I had to make a few small tweaks but otherwise just followed the LLM instructions and it worked great.

When I highlight and right click a drug, I can go right to MedlinePlus search results. When I highlight and right click a researcher, I can go right to ORCID.

I don’t think this is a panacea but libraries could consider pushing something like this out to their users during orientations. It works for me so I figured I’d share. Thanks!

That’s a great approach, Jacob. As you say, it’s probably too daunting / “out there” (not too *complicated*, I agree, but just too *advanced*) for most users to do of their own volition, but it could signpost a potential way forward – could we as a sector suggest that LLMs offer a “scholarly toggle” that basically does this for users. Thank you for sharing!

Regarding “Redefining what Fair Use means and creating licensing or royalty frameworks for derivative content”: It is unlikely publishers can redefine fair use. It is already defined in Title 17 of the US Code, Section 107 (https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/107), and one judge has ruled that training LLMs on legally acquired copyrighted materials is a transformative fair use. Most legal scholars I follow indicate that other judges will rule similarly. Here are two quotes from Judge Alsup’s opinion in Bartz v. Anthropic: “the use of the books at issue to train Claude and its precursors was exceedingly transformative and was a fair use under Section 107 of the Copyright Act.” And “the ‘purpose and character’ of using works to train LLMs was transformative — spectacularly so.” (https://docs.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/california/candce/3:2024cv05417/434709/231)

The settlement in this case and Anthropic’s historic payout to copyright holders are not about fair use. They are the result of Anthropic using illegally acquired materials in some instances to do the training.

Thanks, Jody. But does *training* an LLM include the subsequent creation of derivative content, without proper attribution? (I have no idea. V much not my area of expertise!) I also don’t know that I’m suggesting *publishers* redefine Fair Use. I feel like this is an issue for the whole schol comms sector and ultimately it’s researchers / scholars (and by extension their institutions / funders?) who lose out if they don’t get acknowledgement / recognition for how their work is reused. That’s the breadth of mindset from which I’ll be approaching this study and its recommendations, anyway!

It’s not as clear-cut as you suggest.

“Fair use” is a multi-part test including assessment of the impact on the copyright holder’s business model. In the US Supreme Court case of Grokster (decided in favor of copyright holders) this was a key consideration.

In the more recent Supreme Court case of Warhol, “commercial purpose” was elevated as a factor to determine whether copying was unfair.

Transforming a copyright work into a probabilistic model is no more transformative than converting the same work into imprecisely positioned ink and pulp atoms using a photocopier.

When it comes to copyright, there is everything to fight for! For this reason, journals/publishers should carefully document any detrimental impact AI has on their usage data and business model.