For the first time since 2009, the Public Library of Science announced that they were hiking the price of publishing in PLOS ONE by $145, from $1350 to $1495–an increase of 11%. Compared to increases in the costs of living or higher education in the United States, this rate hike barely covers inflation. So, why did such a small price increase arouse such a negative reaction from open access advocates?

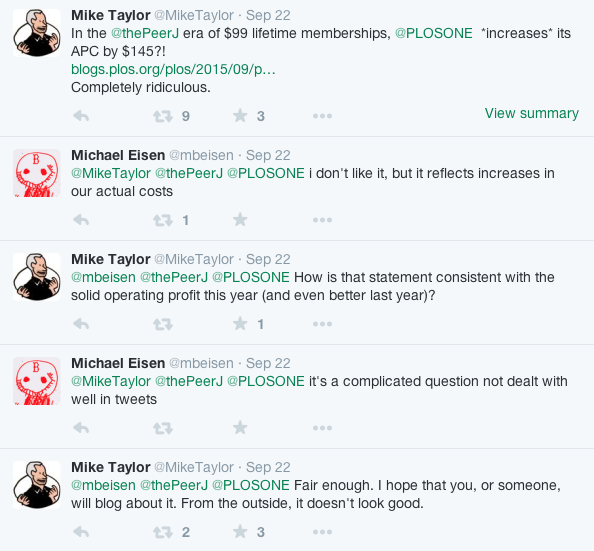

In the following public Twitter exchange, Michael Eisen, who sits on PLOS’ Board of Directors, defends the publisher’s price hike, justifying their decision on the growing costs of publishing. If you didn’t know Michael Eisen, you might be convinced that the responses were coming from the Director of Public Relations at a large commercial publishing house:

Now granted, PeerJ does not charge $99 per paper, but applies membership fees starting at $99 per author, so the comparison is not accurate. However, the argument that open access publishing can be done much cheaper is shared by many OA advocates.

If you look at the PLOS’ latest financial statement, it appears that PLOS operates more like a commercial publisher than a charity. In 2014, the not-for-profit publisher made $4.9 million surplus on $48.5 million in revenue. The vast majority of this revenue came from article processing fees for papers published in PLOS ONE, which numbered more than 33,000. PLOS’ profit margins are some of the highest in the industry, making one wonder why such a profitable non-for-profit needed to raise rates.

I should note that PLOS is only raising its publication fees for PLOS ONE and leaves its other journals untouched, in spite of the fact that current article processing charges (APCs) do not cover their operating expenses, according to Eisen. Profits from PLOS ONE continue to subsidize PLOS’ more selective titles.

According to the official PLOS blog, publication fee hikes for PLOS ONE were justified by improvements in the quality of PLOS ONE publishing, along with ongoing development of a new manuscript submission system called Aptera. Describing the current systems being used by PLOS, Eisen tweeted, “we cobbled together systems over time and there’s just a lot of manual steps in process.” In other words, the ultimate goal of PLOS ONE is to keep prices stable through automation, high acceptance rates, and high volume publishing. It does make me wonder whether other publishers can truly offer competing services at much lower rates. In its third year of publishing, output from PeerJ is tiny compared to PLOS ONE.

In spite of social media uproar, I still have a hard time viewing PLOS ONE‘s rate hike announcement as controversial, even newsworthy. To me, it simply reflects a newfound dedication to longterm planning and financial sustainability. Ideology, even for its board of directors, is slowly being tempered by pragmatism:

The turbulence we hear may be PLOS’ second wave of pragmatism colliding with fundamentalist open access ideology — that publishing needs to be done cheaply while including all of the services demanded by authors. These arguments are still being made by disgruntled academics, librarians, and scrappy startups — groups that dream of becoming a disruptive force in science publishing but have little to lose. Fifteen years later and $50 million annual revenue, PLOS is in a real position to effect change, but may find itself like most other incumbent publishers, growing conservative and protective of its assets.

Discussion

31 Thoughts on "When Pragmatism Collides With Fundamentalism-PLOS Hikes Publication Fees"

“PLOS’ profit margins are some of the highest in the industry”. I think this statement could do with a bit more context. In publishers of similar sized outputs, profits are much higher: https://alexholcombe.wordpress.com/2013/01/09/scholarly-publishers-and-their-high-profits/ Both in terms of real cash, and as a percentage of operating costs. I think we should wait for a more detailed announcement before jumping to conclusions about PLOS and other OA publishers!

The three publishers listed in that article, Elsevier, Wiley and Springer, all publish thousands of journals, while PLOS publishes 7. So, suggesting that PLOS is “of similar sized outputs” is incorrect. PLOS is, however, one of the more profitable of not-for-profit publishers, and one of the more profitable smaller publishers, at least by margin, and it’s worth noting that this year’s 12% margin is a big drop-off compared to previous years (21% in 2012 and 2013) , likely due to the noted reinvestment in their technology platform.

That depends on how you measure outputs – in terms of number of journals or number of papers (I was going for the latter!). Either way, still waiting for a more detailed breakdown of how this new increase in APC is justified.

See comment below. Detailed financial information from PLOS is available here:

https://www.plos.org/about/plos/progress-update/ and from Guidestar via their 990 forms.

PLoS may only publish 7 journals, but it publishes the largest (by far) journal: PLoS ONE. Counting articles is more accurate than counting journals: with roughly 35,000 journal papers in 2014, PLoS is the 11th largest journal paper publisher. Wiley is 4.5x larger, Springer 8x larger and Elsevier 16x larger in terms of journal papers: http://sciforum.net/statistics/top-publishers-by-articles

My point exactly. Even counting by number of papers, PLOS is still dwarfed by the massive commercial publishers. There are enormous benefits of scale, hence higher margins. Each journal at Elsevier only has to cover a very small portion of its overall platform. Any individual journal has to carry 1/7 of PLOS’ platform expenses. They are very different beasts. A more realistic comparison would be to publishers who offer a similar number of articles and operate on a not-for-profit basis. Even given all that, PLOS is in the higher end of things margin-wise, operating at above a 20% margin for 2 of the last 3 years.

I think that Elsevier, as a subscription publisher, has a totally different approach to its infrastructure and platform architecture than PLoS. I bet that PLoS is completely cloud-hosted with cloud-based backup versions and cloud-based archive versions of their content, and thus at a fraction of the cost of the Elsevier own-run infrastructure: Elsevier, through Reed Elsevier Network Management Center and LexisNexis, runs its own data centers and has even its peering contracts with several large network operators. At a rough glimpse (http://bgp.he.net/AS1757) it looks like there at least 3 data centers, probably two within larger data centers operated by Verizon and others…

Regardless, I think it’s fair to say that PLOS has been an enormous success, certainly on a business level, out-earning most of their counterparts and driving margins beyond those seen by all publishers except the largest commercial firms (and possibly Hindawi, which at last report had margins above 50%).

Phil, I do not agree with “PLOS’ profit margins are some of the highest in the industry”. Elsevier who dominates the journal paper market with a 24% market share (http://sciforum.net/statistics) makes a 30% overall profit margin (Reed Elsevier). The STM publishing division of Elsevier, by far the largest and most profitable division of Elsevier, is at 37% operating profit margin (see page 12, http://www.relx.com/investorcentre/reports%202007/Documents/2014/relxgroup_ar_2014.pdf).

Had to look up “scrappy” in a dictionary. It’s either “full of fighting spirit” or “composed of scraps”. Now having an identity crisis.

“However, the argument that open access publishing can be done much cheaper is shared by many OA advocates.”

Usually the same small group of people who seem to have a lot of time on their hands to spend on twitter, blogs, forums etc., but have never tried to run a publishing company.

Except for OA advocates who support initiatives like arXiv, Rio, Cogent, the Open Library of Humanities, SciELO etc., which all demonstrate that publishing in general can be done for much cheaper than is charged by legacy publishers.

I don’t know that PLOS has high margins, relatively speaking. I work with many organizations that drop 20% or more to the bottom line. All of these are not-for-profits. A high margin is an expression of effective management. It should also be a signal for others to get into the business. As Jeff Bezos says, your margin is my opportunity.

Or perhaps I stand corrected. I’ve generally worked for not-for-profit presses that run at lower margins than seen here.

There are high margins among professional societies with large programs. Are there perhaps two dozen of these? I don’t know. One could find out by spending a weekend inside the online forms 990. But in my view this is beside the point. A high margin nowadays is viewed as a sign of greed, which is simply wrong. It’s a sign of strong management. And I repeat Bezos’s wisecrack: Your margin is my opportunity.

“PLOS’ profit margins are some of the highest in the industry,…” I’d be interested to see the figures on which this statement is based.

See reports for 2012, 2013 and 2014 here:

https://www.plos.org/about/plos/progress-update/

Thanks but the statement implies a comparison has been made – that’s the information I am looking for. From what I understand of the figures published in the annual reports of the largest publishers who dominate the marketplace (Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, T&F) – though I’m no financial analyst – they all have bigger margins. So might one equally have written “PLOS’ profit margins are not some of the highest in the industry,…”?

Would the author like to comment on his reading of the evidence?

There are over 2,000 academic publishers. The four you mention do indeed make higher margins than PLOS. That leaves 1,996, and as far as I know, very few of them make a profit margin above 20%. Certainly it’s rare in the not-for-profit realm. For example, compare PLOS’ margins to those of the biggest and most profitable university presses, OUP and CUP, both of whom post public annual financial reports.

“That leaves 1,996, and as far as I know, very few of them make a profit margin above 20%.”

Well, that brings me back to the original question. How far do you know exactly? How many of the 1,996 have you (or the author) checked out? It would seem more reasonable to compare PLOS to other publishers that have significant market share, say the top 15 here (http://sciforum.net/statistics/top-publishers-by-articles). Worth noting I think that Hindawi boasts (or it did) a margin of around 50%. So again, perhaps PLOS doesn’t have ones of the highest margins etc?

Worth also noting that PLOS’s margins aren’t profits (some of which are distributed to shareholders) but surpluses that are ploughed back into the organisation. I think it would be worrisome if non-profit publishers were making very large margins year on year and I’m not particularly thrilled by PLOS ONE’s price increase but where I agree with the author is that the operation needs to be sustainable. Unless, of course, they are out-competed by another organisation offering an equivalent service at a better price…

I agree that it’s better to think in context with other not-for-profits. The AAUP has 133 members, the majority of whom rely on subventions from their universities to cover costs. Looking at your list and the publishers who publish around the same number of articles as PLOS, financial reports are available from the likes of OUP, CUP, ACS, RSC, and IEEE. Would love to dig out publishing margins for you but am off to the airport right now…

This is all just weird. PLOS kept prices the same for 6 years and yet no-one says well done for that achievement. Most businesses (whether ‘for profit’ or ‘for surplus’) experience rising costs. Eventually that has to be passed on somewhere, or they go bust. The majority pass it on quicker.

I don’t see why PLOS should be singled out for this in this article.

And nor do I understand why commentators are making some kind of of virtue over them being not the most profitable operation out there. How on earth does defending PLOS’s surplus absolutely or comparatively bring clarity to the debate?

The question surely, as a user, is whether or not they provide a valuable service (however youy define valuable to yourself). If yes, continue using and extolling them.

If not, go elsewhere or – better still – start your own operation to provide the value(s) you want from scholarly publishing.

And if you believe publishing should be free for authors and readers, then they just found water on Mars and so maybe there is an alternate world to be built.

I agree with Martin – but there’s a twist in defining “valuable”.

Nothing is free. Someone *always* pays. For example, many services in internet are free for us, because someone else pays to get access to our attention, or opinions, or behavioural data, without asking our permission (and I now notice it is apparently free for me to write this comment…).

Nothing is cheap, either. Someone *always* pays the full value. For example, clothes and gadgets and the mess of getting rid of them are incredibly cheap for us, because some child in the far east works as a slave to pay daddy’s debts and her master does not have to worry about healthcare costs when the fumes make her sick (and I now notice I’ve got six kinds of computers here, all of which I bought without noticeable drain on *my* living standards…) .

Too many people forget that. Often the world is better where the things I get are paid by me or from my taxes instead, with a fair amount.

Almost all of academic authoring and reading is ultimately paid by taxes or donations, regardless of user’s or provider’s operating model. And I suppose with a fair amount, given that most readers of this get a decent living from some side of that transaction. Comparatively, there’s very little exploitation of anyone (just a lot of silliness and smart people doing stupid things, but that’s another story).

So. PLOS price hike is just fine, and so is Elsevier’s profit margin.

To be fair, in the US much of subscription revenue comes from tuition payments and student fees. Not sure that any parent with a kid in college would call that a “donation”.

Mea culpa.

With the risk of being a bit of a troll… It’s wonderful how US and UK (except Scotland) are such rich countries they can afford to deny higher education from some of their talented young – poorer countries have to make do with taxpayer-funded education all the way up to PhD.

Someone posted an interesting article last week:

http://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2015/09/lsu-debt-free-college/406555/

I’d second the comment from Martin.

Any start-up company that grows and has an element of success runs into various issues as it scales. The cost of employing more people, paying them more money, or the cost of pensions, bringing in more software developers to scale up the platform. Invariably that means passing on some of the cost to the customer, eventually, in the form of higher prices.

This is particularly the case if the company is based in London, New York or other big cities where the cost of living has become crazy, and you wish to retain younger staff, who are invariably recent graduates with student debts. Added to that, when you step outside pure publishing roles-software developer, lawyers, accountants-you have to pay the going rate for those sectors, which is going to be higher than most standard publishing rolesin editorial, editorial office or production.

The alternative is to be a miserly and cynical employer, and treat your staff like lab-rats.. I remember interviewing at a company in 2011, a well-known place for building new STM publishing ventures and then selling them to the big corporates When I enquired about pensions at the company the reply was the famous “Mr X” who had started one of the best known OA ventures and then sold it for a zillion pounds to a corporate, “didn’t like to offer pensions because he wanted to keep operating costs lean for his ventures, so that he can sell them when they become profitable.

I am amazed how much faith everyone is placing in the margin. Having run a number of companies the margin is often a number that is at best artificial and reflects the accounting practices and expectations of the people the results are prepared for. Often expenditures are timed to hit the books at the appropriate time. Margins can easily be improved or lowered based on the management.