As one former publisher, now consultant, told me, “a consultant is someone who steals your watch to tell you what time it is.” That is, a consultant is someone who tells you exactly what you already know, but want to hear again for reassurance sake.

In a particularly cogent article, Open Access 2.0, published in the June issue of the The Journal of Electronic Publishing, Joe Esposito lays out many things that we don’t know – or at least are not willing to admit – about publishing. This is not a collection of declarative diatribes loosely held together with non-sequiturs, or a pronouncement of how we’ve done good in our company/library. It is one of the few articles based on theory – in this case economic theory – and how it helps us to understand and predict the successes and failures of publishing.

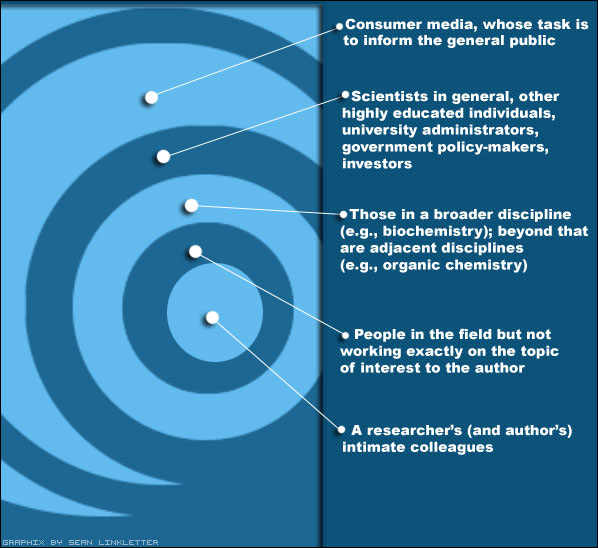

The basis of Esposito’s argument is that the publishing economy’s limited resource is not access, but attention, and that the role of traditional publishing is to help readers decide what is worth their time reading. This job is done essentially through filtering (also known as gatekeeping).

And yet Esposito does not discount other forms of publishing that allows everything to come through the gate, and to filter and evaluate later. Thus he sees places for the role of Open Access and repository publishing, only he believes that these forms of publishing should occupy different market niches. In this sense, Joe goes beyond the typical rhetorical and binary argument of open or closed, but sees a plurality of publishing markets for reaching a plurality of reader communities. Similar to the argument of viewing the automobile as simply a horseless carriage Esposito writes:

One of the reasons that many open-access ventures have had a hard time financially is that they have been built on the mistaken assumption that they are replacing traditional publishing and thus have to re-create all of the services that traditional publishers now provide.

For pure OA publishing, he sees stripped-down models that attempt to minimize the role of human involvement and to maximize automation. For instance, he views a university librarian spending time coaching a faculty member on how to deposit a manuscript into the institution’s repository as both overly expensive (in the time of a highly-paid administrator) and unsustainable.

In spite of his insistence on avoiding the binary pro-against open access, Esposito creates another dichotomy between supporting readers (the traditional subscription market) or authors (the author-paid OA market). Part of this dichotomy may be used for rhetorical purposes and to strengthen the force of his argument. Nevertheless, this is one article from which both sides of the open access debate can read, agree, and learn.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Open Access 2.0: When Free Gets Expensive"

I followed over from Bench Marks.

As a researcher who has published for many years, I have to agree that OA and traditional approaches are not binary and that both will have their place.

However, their focus is not on author or reader. It is currently on author and subscriber.

Many journals are too expensive for me to subscribe to. Apparently only libraries can. And as a reader they charge men upwards of $60. I am not well served by this approach.

I am better served by association-based pseudo-OA journals that give me free access after say 6 months but only charge me $5 to read the article before then.

These journals join up authors, members, subscribers and readers into a potent mix that may come to dominant scientific publishing.

I found your site on technorati and read a few of your other posts. Keep up the good work. I just added your RSS feed to my Google News Reader. Looking forward to reading more from you down the road!

How is Open Access Publishing able to happen without Peer Review? I was told that the publishers organize the Peer Review Panel, and they determine whether a scholarly piece is worthy to be published.

Can something be published without the standard Peer Review panel?