(Editor’s Note: This is the second of a two-part series. The first part, “Creating a New University Press,” appeared yesterday.)

As noted in the first part of this two-part series, established university presses have neither the luxury nor the necessity to speculate about setting up shop across the street as independent entities. For better or worse, their fate is tied to their relationship with their parent institutions. Their strategy naturally differs from that of an entirely new press, as the environment they operate in is structurally different. I wish to underscore this point: the strategies of an established organization and a start-up company are necessarily different. Much angst is incurred by established companies that mistakenly believe that strategy is strategy, that one size fits all. This error in thinking is beautifully and inadvertently captured in the title of Jeff Jarvis’s book, “What Would Google Do?”

What’s good for the Google is not necessarily what’s good for the gander.

Contemplating the creation of a new press makes it very clear that the biggest obstacle to starting something entirely new is that the established publishers are very good at what they do and would be hard to displace. I know that many people feel otherwise about the university press world today, but I simply cannot agree with them. The press world is indeed under considerable pressure, but it’s not as though someone could come along and say, “I can do a better job than Columbia or Indiana” and jump in and swiftly become successful. The presses have established networks to draw on, important brands, and know-how in critical areas. To compete with the presses today does not call for a new press; it calls for a new idea.

The established presses might do well to examine precisely where and how they would be hard to displace. I have written about this before, but a good place to start is with Peter Dougherty’s (Director, Princeton University Press) “manifesto” on scholarly publishing, which makes a case for “the character of our content.” If publishing good books with hard ideas is among the things that an established press does well, and if this activity represents one of the barriers to entry for new academic publishers, then it makes perfect, strategic sense for a press to continue to do this and even augment its activity in this area. Thus, the reports of some presses cutting back on title output seems misplaced to me. Better to align a book program with emerging fields, especially if they are supported by the parent institution, than to scale back the operation. For if a press decides to cut back on books in order to pursue new ventures (sometimes masked by the phrase “a new business model”), the press will be entering an area where a start-up organization can compete on equal terms.

Indeed, an established press should not cede an inch to an upstart in the established press’s territory. This means that the thing that presses uniquely do very well (publish important books about ideas) should be extended everywhere: in print, in print on demand, in every digital file format, for every reading device, in digital aggregations for libraries, and in the emerging methods of marketing directly to end-users (D2C for direct to consumer). It is a matter of semantics whether one would call this “innovation.” I would not; I would reserve the term for the truly new. But extending a franchise to new formats and new market segments requires insight and energy, and all established presses must engage in this.

An established press must also be on guard when an upstart publisher attempts to encroach on the established press’s network of contacts. For example, let’s imagine a university press that has published three books by one author. One day the press discovers that the author has been approached by a new entity to write a 50,000-word essay synthesizing developments in the field, to be marketed as part of a subscription directly to researchers; and what’s more, the piece will not undergo peer review. This is a ticklish situation for an established press. No peer review? Of course, the game being played here is clear: no peer review because the author, not the work, has already met high professional standards (a phenomenon I call “provostial publishing”). And what to do about that D2C subscription model? On the other hand, this is the press’s author. A press in this situation may make the determination that the best strategy is cooptation. And it may not be a good idea to wait too long to get around to doing this.

This is a roundabout way of saying that established presses should look to new publishers in any field as a source of ideas; if you only look to the competition in your own field, you will overlook the barbarians and crazies who are slipping inside the border. While university presses are occupied today with the (important) task of creating large-scale digital collections for academic libraries, they also should be studying the new apps being created for the iPad by educators and game developers and, closer to home, companies such as Morgan & Claypool, an early born-digital publisher that developed a new editorial approach for technical publications. Where is the Morgan & Claypool of Women’s Studies or literary criticism, I wonder. Recently I sat for several hours in a coffee shop with an entrepreneur who showed me one educational app on his iPad after another, the riches of the presentation defined as much by quantity as quality. “Is that all there is to it?” I asked of one app. “That’s the level of development the platform requires,” was his response. Of course, you have to sift through a lot of material before coming away with one good idea. I suppose shoplifters have the same problem.

The difficult balance for an established press is between its historical strengths (the brand, the book and journal formats, diversified distribution channels, a network of authors and advisors) and the compelling, often mandated, changes in the marketplace. We know when a press can be too conservative; everyone picks on them all the time; some librarians like to hoot about how backward presses are digitally. But presses can also be too daring at times. Many got involved with digital projects early on that did not pan out, costing the presses scarce investment capital and, worse, souring them on future experimentation. The key is to exercise mature judgment (humanities students take note!) without being unduly conservative.

Upstart publishers will challenge established publishers on many fronts, but which are the challenges that must be met, which coopted, which ignored? Ebooks–yes, do that, and do it quickly (most presses already are). And texts of intermediate length, neither article nor book–yes, do that before an entrepreneur begins to siphon off your authors. A pause may be in order, however, when presented with some of the publishing programs now being initiated in libraries. Libraries are fundamentally different from publishing concerns, and the publishing programs libraries are incubating may not be something to copy or to try to coopt. This does not for a minute mean that these programs are without value; it simply means that there are activities that presses may be wise to avoid.

The term “library publishing” covers a lot of ground. I am referring here to the creation of open access institutional repositories. It’s not relevant to my point what kind of content goes into them, whether copies of faculty papers, student papers, digitized books, scanned collections of primary documents, and so on. Publishers may have specific reservations about some of these items (Are the digitized books still under copyright?), but the real issue is one of business model.

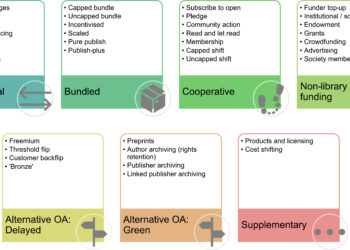

As noted on the Kitchen before, publishers have four ways and no more to finance their operations. They can have users or their proxies pay for content (the traditional model); they can have authors or their proxies pay for publication services (the model used by PLOS and SAGE Open, among others); they can earn revenue through the aggregation and packaging of audiences to sell advertising and other marketing services; or they can seek support either from a parent institution or other supporting group (e.g., wealthy individuals, grants, etc.). Many organizations have hybrid models (e.g., sell subscriptions AND sell advertising), but even the hybrids have only four kinds of revenue streams to work with. Library publishing falls into the fourth category, where the business model is, like that of a library’s traditional functions, supported primarily by an institutional sponsor.

The fundamental difference between libraries and publishers is not found in the mission statements, which may sound very much alike–and may sound like the mission statements of a thousand other organizations. The important difference is that libraries are set up as cost centers, whereas university publishers are set up as subsidized profit centers. This means that publishers have earned revenue through the sale of books and journals. With university presses under so much financial pressure right now, taking on projects that will effectively increase the requirement of institutional funding is not a prudent step. Most universities would like their presses to fund themelves entirely as profit centers without requiring a subsidy at all.

It may come as a surprise, then, to find a growing number of presses being placed organizationally within academic libraries. The declared reasons have to do with shared mssions, shared goals, and synergistic operations, but I suspect administrative convenience is a big part of it. Let’s imagine a press with costs of $5 million a year and revenue of $4.5 million. The deficit of $500,000 is made up by the parent university. In financially challenging times, the university administration may have to justify that subsidy to the institution’s governing board. On the other side of the campus is the library, a cost center with a budget of $25 million a year. If you roll the press’s half-million-dollar loss (a loss because this is what shortfalls in profit centers are called) into the library’s overall budget, the problem of the press’s subsidy seems to disappear. This is what is known as synergy.

While upstart programs wherever they emerge can often serve as good if unwitting sources of inspiration for established presses, it is important that they not be taken on their own terms. Open access, for example, was once thought to be a tool that would topple the entire STM publishing establishment. Now it is evolving into yet another profit center for a number of publishers, some of them in the for-profit world. Established presses should study start-ups carefully and learn from them, but resist any temptation to go native. To take on the worldview of the upstarts gives too much away, all that has accumulated in an extablished publisher’s brand and practices.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "What Upstarts Can Teach Established Presses"

“If you roll the press’s half-million-dollar loss into the library’s overall budget, the problem of the press’s subsidy seems to disappear. This is what is known as synergy.”

You’re a cold, cold man, Joe. 🙂

Just two quick points: 1) I don’t know of any AAUP-member press that could offer to publish an author’s book entirely without peer review of any kind. That would be counter to AAUP membership requirements. What might happen is that the press’s editorial board might delegate its authority to accept a book to a series editor. But I can’t see no peer review at all occurring. 2) When presses are merged with libraries, their budgets are not always merged. Ours at Penn State remained separate from the library’s budget after merger.