Stephen Jay Gould, in his famous essay about Joe DiMaggio’s hitting streak, explained why the human brain so often has a hard time understanding the scientific data of a random universe:

We must have comforting answers. We see pattern, for pattern surely exists, even in a purely random world. (Only a highly nonrandom universe could possibly cancel out the clumping that we perceive as pattern. We think we see constellations because the stars are dispersed at random in the heavens, and therefore clump in our sight.) Our error lies not in the perception of pattern but in automatically imbuing pattern with meaning, especially with meaning that can bring us comfort, or dispel confusion…We believe in “hot hands” because we must impart meaning to a pattern—and we like meanings that tell stories about heroism, valor, and excellence. We believe that long streaks and slumps must have direct causes internal to the sequence itself, and we have no feel for the frequency and length of sequences in random data.

William Gibson explored similar themes in his novel Pattern Recognition, how evolutionary adaptations to seeing patterns (the plant with leaves shaped like this tastes good, this shape is poison, big animals with sharp teeth should be avoided) continue to drive the way we see the world.

Which is why for so many people a really good story so often trumps hard data (e.g., creationism, anti-vaccine sentiments). But science itself is filled with wonderful stories, and The Story Collider offers a growing collection of them:

Science surrounds us. Even when we don’t notice it, science touches almost every part of our lives. At the Story Collider, we believe that everyone has a story about science—a story about how science made a difference, affected them, or changed them on a personal and emotional level. We find those stories and share them in live shows and on our podcast. Sometimes, it’s even funny.

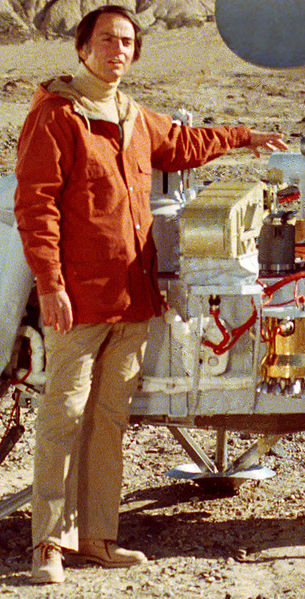

Here’s an example, a wonderful story in which Carl Sagan finds a surprising ally in the battle to separate fact from myth: