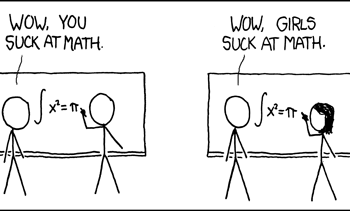

The American academic and cultural heritage communities are not keeping up with societal needs for diversity, equity, and inclusion. My fellow chefs Alice Meadows, Charlie Rapple, and Robert Harington have written about gender inequities in scholarly publishing. In other sectors that colleagues and I have studied in depth, including art museums nationally, cultural organizations broadly and dance companies specifically in New York City, and academic libraries, inequities on the basis of race and ethnicity are if anything greater than those around gender. Gender imbalances remain, stark in some cases, but can at least sometimes be assessed to be moving in the right direction. Race and ethnicity indicate profound differences that we continue to struggle to resolve.

In terms of representative diversity — basic employee demographics — the numbers are especially problematic when one focuses on the “intellectual” leaders in our organizations. Looking in art museums, for example, those who shape the strategic direction, collections policy, and community engagement — the directors, curators, educators, and conservators — are fully 84% white non-Hispanic. While other departments, such as security and facilities, bring greater representative diversity, the result is substantial inequity inside of organizations and an ongoing inability to engage with the cultural and intellectual needs of the society that is changing around us.

For scholarly publishers, individuals involved in setting business and editorial strategy are two broad areas where we should question whether “intellectual” leadership is diverse or diversifying. Larger publishers have an array of individuals with responsibility for strategy, product development, mergers & acquisitions, and so forth. And while smaller publishers may have less of this business infrastructure, all publishers have individuals responsible for editorial work, in particular the selection of what it is that will be published. In all roles, but perhaps especially these types of roles in scholarly publishing, diversity matters.

For this reason, I was especially interested to learn about the University Press Diversity Fellowship Program, an initiative designed to diversify the acquisitions departments at university presses. Last week, I had a chance to speak with Larin McLaughlin, the editor in chief of the University of Washington Press who has spearheaded the fellowship program, to learn more about it.

This initiative, led by the University of Washington Press and including the Duke University Press, the MIT Press, and the University of Georgia Press, is funded by The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and also supported by the Association of American University Presses. Mellon has been building on its long-standing work to diversify the professoriate with a series of research projects and initiatives to bring diversity to various parts of the cultural, library, and scholarly communications sectors.

The University Press Diversity Fellowship program arises from a sense that the acquisitions editor positions at university presses are among the least diverse in scholarly publishing. Each of the four participating presses will, over each of three years, hire a paid fellow for its acquisitions department, for 12 fellows in total through the program. Many fellows will have a graduate education and an interest in scholarly publishing, and all are required to demonstrate a “commitment to using an understanding of the diversity of human experiences in developing, recruiting, and marketing manuscripts and books.”

The fellows are compensated as junior members of the acquisitions department (at an editorial assistant or assistant editor level). This stands to be a great equalizer given that so many individuals get into university press publishing through unpaid internships, with well-understood negative equity implications. And they are expected to take on the standard work of individuals in these positions: screening manuscript proposals, examining competing books, facilitating the peer review process, and so forth.

In addition to learning on the job, fellows are provided a series of professional development engagements. There are a series of webinars for the fellows on topics related to the acquisitions editors position and beyond, for example on managing a P&L. And fellows are provided with free registrations to two AAUP meetings, one towards the beginning of their fellowship and a second towards the end, affording substantial networking opportunities and a vehicle to learn about broader trends in this community.

McLaughlin and colleagues hope that many if not all of the fellows will pursue a career in in scholarly publishing. In that sense, the program can be described as trying to build a “pipeline” of acquisitions editors, who over time can potentially take on more responsibility as intellectual leaders of university presses and in the community broadly. It is important though to distinguish unambiguously what is meant by “pipeline.”

Sometimes, leaders looking at their dismal employee demographics blame the “pipeline” of potential employees, i.e., the pool from which they recruit. This rhetoric is sometimes deployed to displace blame for a lack of diversity: “What a shame there are not more people of color with the appropriate qualifications,” is sometimes a way to blame PhD programs, MLS programs, and other “pipelines.” This lament is surely easier than taking responsibility for the diversity of one’s own organization, by reassessing job requirements, organizational culture, and strategies for sourcing talent, among other efforts.

The University Press Diversity Fellowship program is not a lament at how the pipeline is limited but rather a recognition that university presses can take responsibility for expanding their own recruiting pool directly. It is broadly similar to the ACRL Diversity Alliance, in which academic libraries recruit junior “residents” to increase the diversity of their organizations and ultimately the library profession. In both cases, participants recognize that there are enough qualified individuals for these positions but that there is a need for structured programs to recruit them into traditionally unwelcoming sectors and develop them professionally.

The University Press Diversity Fellowship program is not a lament at how the pipeline is limited but rather a recognition that university presses can take responsibility for expanding their own recruiting pool directly.

The Fellows are recruited through a joint effort of the recruiting departments of the four presses. Coordination across HR structures — whether simply to announce and recruit for a program such as this one or deeper work to standardize position descriptions and application processes — is a complicated but worthy undertaking to improve recruitment. And the four presses are taking on some substantial recruiting efforts individually and collectively, to include:

- Collective recruitment and through the individual campuses

- Recruitment through each press’s author networks to reach graduate students

- Outreach to campus diversity offices and to regional minority serving institutions like HBCUs, HSIs, and tribal colleges.

Looking at the recruiting work to date, McLaughlin notes that the fellowship has generated “really stellar pools — very competitive — with really highly qualified candidates and really amazing finalists.” Perhaps most importantly, she is convinced that the recruitment has brought in a number of individuals who would not otherwise have been interested in a university press position – thereby expanding the number of qualified people of color in the process.

This program appears likely to generate a modest but steady increase in the diversity of intellectual leadership in the university press sector. After the funded start-up cycle, one hopes that the presses will be able to continue investing in positions like these ones, but the responsibility need not fall on these four publishers alone. Looking at other university presses, and beyond to society and commercial publishers as well, what aspects of this program could be applied more broadly? Given their scale, the largest publishers could have programs such as this one operate internally. For smaller and medium-sized publishers, is there a way to assign some set of junior positions to a fellowship program such as this one, thereby limiting its costs to the professional development that might be coordinated through SSP, AAUP, PSP/AAP, STM, the Library Publishing Coalition, or a similar organization? And, given that these issues are not restricted to publishers but cut across organizations devoted to scholarly communications and cultural heritage such as libraries and museums, would a broader alliance here have any merit? Please use the comments to share your reactions and suggestions.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "Diversifying the Intellectual Leadership of Scholarly Publishing"

Excellent post on enhancing diversity in scholarly publishing.

Question: amongst academia societies, one usually finds a caucus specifically

on LGBTQ diversity and inclusivity–except in scholarly publishing. Is this

an area of potential interest? Feedback would be welcomed.

Thank you for the details on what appears to be a very thoughtful and well-designed initiative. The idea of an eventual broader coalition is worthy of consideration.

I look forward to seeing the results of this pilot and what happens post-fellowship re retention. I believe that librarianship has as great, if not greater, problem with retention as with recruitment. Unless “traditionally unwelcoming sectors” transform broadly, I fear such recruitment efforts sometimes have minimal impact.

“Applicants must be citizens, nationals, or permanent residents of the U.S., or individuals granted deferred action status under the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals Program.”

Kind of goes against the whole ‘diversity’ idea behind it, doesn’t it?

After a plenary session at the annual AAUP meeting devoted to diversity in the profession, I sent the following information to AAUP’s new president, Nicole Mitchell:

Over the full course of AAUP history there have been 53 male presidents and 14 female presidents, including you. But there were 23 male presidents before Miriam Brokaw filled out the term of Howard Bowen in 1974/75 and there were 12 more men before Carol Orr was the first president to have a full term in 1987/88. Thereafter there have been 18 men and 12 women. But we are getting close to equity. Since 2000 there have been 10 male and 8 female presidents.

The picture for press directors is not so rosy. I looked at only university presses based in the US and attached to universities (so did not count AAUP members like Brookings, National Academies Press, RAND, etc.), but here is the total of those I counted: 53 male press directors and 35 female directors. There are several interim directors serving now, and most of those are male, so these numbers may shift slightly when the new hires are in place. And I did count PUP [Princeton] as having a female press director. This is not terrible and is, of course, very different from what it was when I began my career in 1967, but perhaps WISP’s work is not completely done after all. [WISP, Women in Scholarly Publishing, founded in 1980, was dedicated to increasing gender diversity in scholarly publishing. It disbanded sometime after 2000.]

Clearly, there has been nothing like this progress for racial and ethnic diversity in the profession despite efforts the AAUP made in the mid-1990s when it had a Diversity Committee focused on the task. It is good that the AAUP is trying again. To a certain extent, sheer demographic change should help: when I entered Princeton in 1961, my class included just one black and four students of Asian ethnicity; the entering class of 2021 includes 53% people of color.

But change doesn’t come without effort. And even with effort progress can be very slow. Consider these findings from a recent NCAA report about diversity in college coaching:

Little progress has been made diversifying coaching staffs and the leadership of athletics departments, the report shows.

In 1996, nearly 43 percent of women’s teams were led by a female head coach — by 2016 that percentage had dropped to about 40 percent.

On women’s teams, the female head coaches were, and remain, overwhelmingly white.

About 92 percent of head coaches of women’s teams were white women 20 years ago, and in 2016, about 86 percent were white women.

Sandy, I am reflecting on your comment, which mainly provides data about gender. I wondered when I was drafting this post if we have good baseline employee demographic information for the scholarly publishing community. I would be especially interested in data covering race and ethnicity, but in light of Bill Cohen’s question I wonder about LGBT and other categories as well. As you observe, the most intractable issues we face on diversity and inclusion appear anecdotally not to be about gender, but it would be better if we had the evidence on which to base that conclusion for this sector. And in other adjacent sectors, there is all too little evidence to suggest that the kind of progress you observe on gender is taking place with race and ethnicity. It is understandable that many of us are impatient.

It seems to me that these are fields which are very open to people of different backgrounds. Maybe they just aren’t as appealing to those people as a career. I have a hard time imagining librarians and publishers, who tend to have an avid interest in other cultures and experiences and in bringing those to others, intentionally or even unconsciously shutting out diversity. Honestly, these people are the cream of the liberal intellectual crop… just think about the types of museum exhibits and books that are in vogue. If anyone of a different background has had trouble making their way in these fields I’d be fascinated to hear about it. Is it really progress if the people in question aren’t concerned about it?

I agree liberal intellectuals value diversity and are generally welcoming to people of minority backgrounds, but openness and good intentions do not create opportunities for people of color. If discrimination is built into the system, then it doesn’t matter how much a publisher would welcome a non-white worker. How do young people generally start in publishing? Unpaid internships. And who is more able to have the time and support network to commit to (and succeed in) long-term, intensive internships? Those who are already privileged and those who know that these opportunities exist through the networks that have been built over generations. It is true that working in publishing is a tough sell to anyone. How does one compete with tech or medical or business salaries, where entry-level jobs make more than mid-level jobs in academic publishing (and, by the way, these jobs are much easier to obtain without a graduate degree, which seems to be more and more of a requirement in academic publishing)? This is a question for all people considering publishing as a career, and it is an even more difficult question for people of color, who can look at the highest levels of university publishing and see a distinct lack of people who look like them. Deciding to make a career in academic publishing is a huge gamble, and success in the field looks even more daunting to minority candidates.

To say that people of color are not concerned about opportunities and advancement in a field that they may love as much as (or more than) any other feels a bit like blaming them for not caring enough or working harder. The fellowship mentioned in this article is certainly not a quick fix to the problem, but at the very least it communicates that we do want these candidates, and that’s a big deal.