Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Christos Petrou, founder and Chief Analyst at Scholarly Intelligence. Christos is a former analyst of the Web of Science Group at Clarivate Analytics and the Open Access portfolio at Springer Nature. A geneticist by training, he previously worked in agriculture and as a consultant for A.T. Kearney, and he holds an MBA from INSEAD.

Amid ongoing industry disruption (Plan S deliberations in Europe, a rumored executive order in the US, and contentious negotiations for PAR/RAP deals with consortia around the world), news of a changing evaluations policy by the Chinese administration is unlikely to have been welcome news for international publishers.

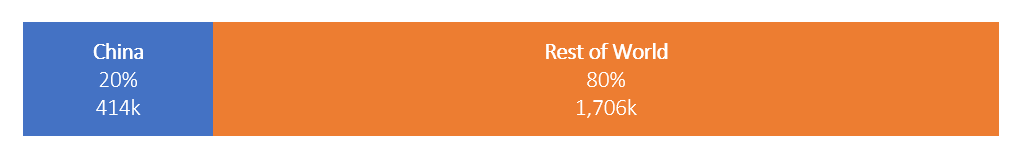

Anything that affects publishing habits in China has the potential to affect domestic and international publishers. According to Clarivate’s Web of Science (WoS), authors affiliated with Chinese organizations contributed to 20% of research articles and review articles (the types of content that matters the most commercially and academically) in 2018 (Figure 1). The share of China exceeds 30% for two of the top eight publishers. Moreover, China has been a key driver of content growth for many international publishers in recent years.

New policy and old habits

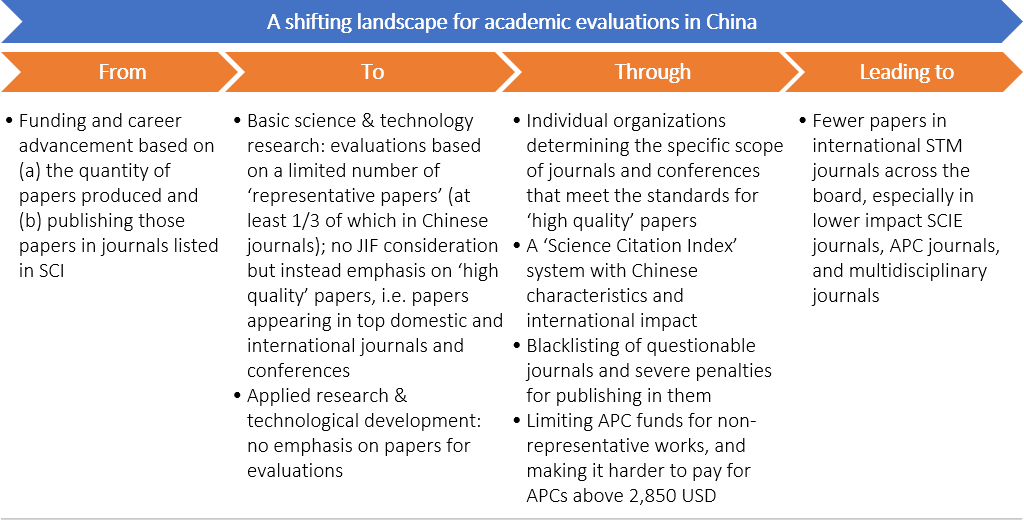

This post by Scholarly Kitchen resident Chef Tao Tao, captures the main points of the two documents that were issued in February. The summary sheet below contains key information from that post, hopefully without much misinterpretation.

The policy dictates a departure from evaluations based on SCI indexed journals (it refers to SCI 31 times in a rather short document). Standing for Science Citation Index Expanded, SCIE (which has replaced SCI) is the foremost index of Clarivate’s Web of Science (WoS). Journals indexed on SCIE (and those on SSCI, the index for Social Sciences) receive a JIF (Journal Impact Factor) and category ranking on an annual basis.

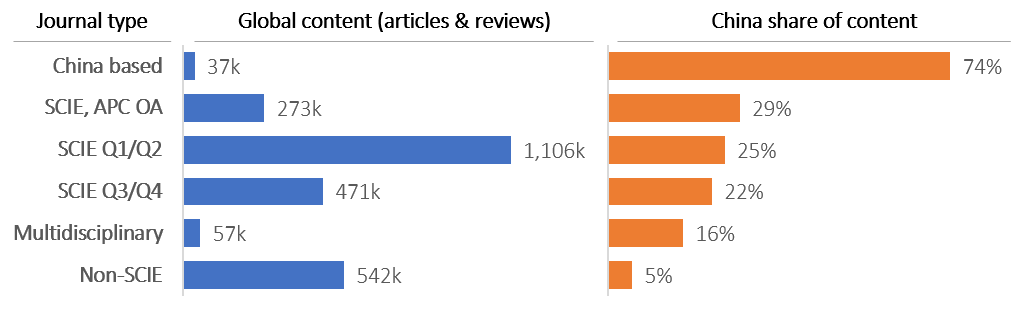

Chinese authors and institutions have been rewarded for publishing in SCIE journals. As shown on Figure 2, authors affiliated to Chinese organizations account for 25% of the article and review content in top SCIE journals (those ranking in the top half of cite-ability in at least one WoS category). Other SCIE journals get 22% of their content from China. On the contrary, journals that are not in SCIE but in one of the other journal indexes of the Core Collection of WoS (SSCI, AHCI, and ESCI) get only 5% of their content from China.

The misbalance between SCIE and other indexes may be the result of stronger Chinese emphasis toward sciences and/or the lack of appeal of international journals in Social Sciences and Humanities for Chinese authors. But it is also likely that it reflects a system of incentives that has driven Chinese researchers towards SCIE journals, especially those with higher impact.

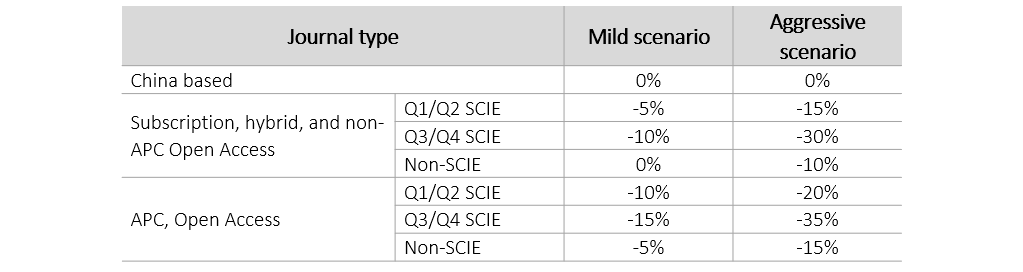

Explanation of journal types: China based: publisher address is shown as China; SCIE, APC OA: indexed in SCIE and showing APC information on DOAJ (fully Open Access); SCIE Q1/Q2: indexed in SCIE and ranking in Q1 or Q2 in at least one category; SCIE Q3/Q4: indexed in SCIE and not ranking in Q1 or Q2 in any category; Multidisciplinary: indexed in SCIE exclusively under the category of Multidisciplinary Sciences; Non-SCIE: indexed in SSCI, AHCI, or ESCI and not in SCIE

Implementation and obstacles

The policy is ambitious in its scope and contradictory in places. For example, setting up an editorially rigorous and accurate index such as SCIE is complex and laborious. The Chinese administration may be able to achieve such a feat through trial, error, and considerable investment, but it is unlikely that it can do that within the next 2-3 years. The same goes for the development of domestic journals with international reach that can absorb a large volume of high quality, domestic literature (despite the investment of $29m per annum in a five-year period).

Moreover, moving away from the JIF is easier said than done. Non-Chinese institutions are also JIF averse, but plenty still rely on it for evaluations, and alternatives have not taken off. For instance, DORA may have almost two thousand organizations as signatories, but only a few hundred appear to be universities. Even if the JIF is no longer used for evaluations in China, researchers will still want to publish in the most impactful, most visible journals, which typically are indexed in SCIE.

Nonetheless, it is likely that Chinese researchers will cut back on the volume of manuscripts. Research will continue to happen and it will need to be published somewhere, but there will be less of drive to ‘salami slice’ (to split up findings into multiple separate papers rather than concentrating them into one stronger publication). SCIE journals with poor ranking and APC journals are likely to be affected the most, the former because they will matter less for evaluation and the latter because of the imposed funding restrictions.

Quantifying the impact

It is too early to accurately forecast the impact of the policy for international publishers. Instead, this analysis tests two scenarios (a ‘mild’ one and an ‘aggressive’ one) of varying paper flight from top SCIE journals, other SCIE journals, non-SCIE journals, and APC, fully Open Access journals in the next 2-3 years, based on 2018 data. The end result is likely to be between the two scenarios.

In both scenarios, it is assumed that (a) content in Chinese journals will be unaffected by the policy (as shown on Figure 2, they are already dominated by Chinese content), (b) non-SCIE journals will be affected less than SCIE journals, (c) top-SCIE journals will be affected less than other SCIE journals, and (d) APC, fully Open Access journals will be further affected. Table 1 below shows the parameters (paper loss from China) that have been fed to the model.

The analysis uses 2018 data from Clarivate’s InCites (which utilizes WoS data) and the Master Journal List for paper output (articles and reviews), publisher, location, categorization, and ranking by journal. Publisher information per journal has been checked against publishers’ lists for more than 30 large publishers, and APC information has been sourced from the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ).

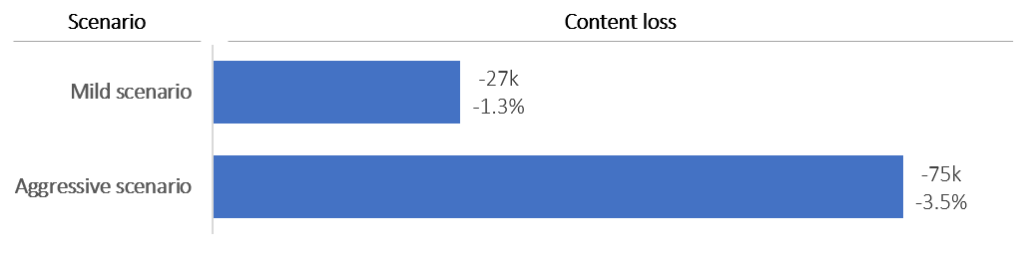

The mild scenario suggests flight of 27k papers, equivalent to 1.3% of all articles and reviews (Figure 3). The aggressive scenario suggests flight of 75k papers, equivalent to 3.5% of all articles and reviews. At a first glance, the impact of the policy does not appear dramatic. While it can negate about a year of content growth across the industry, subscription publishers should be able to weather the storm. Many contracts will be negotiated long after a drop in content (if any) has taken place, and in addition, publishers can argue that the loss concerns the less impactful content of their portfolios.

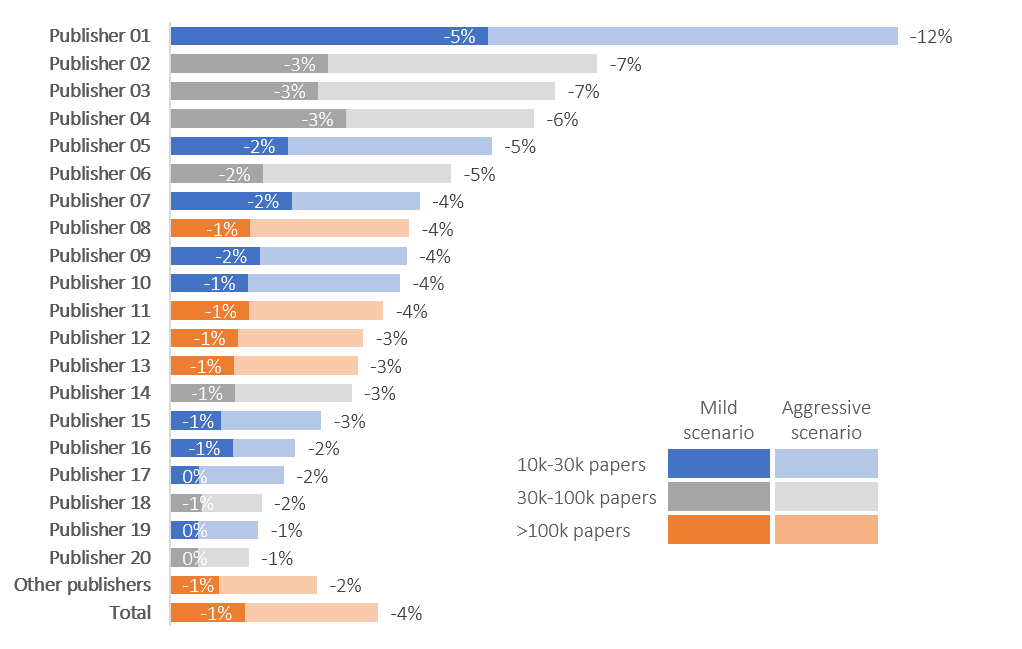

Of course, the impact will vary by publisher (Figure 4). Those that receive a higher proportion of content from China, especially in low impact and/or APC Open Access journals, will lose more content. One publisher is expected to lose 12% of content in the aggressive scenario. At the same time, some other publishers with little exposure to China will be virtually unaffected.

Of course, the impact will vary by publisher (Figure 4). Those that receive a higher proportion of content from China, especially in low impact and/or APC Open Access journals, will lose more content. One publisher is expected to lose 12% of content in the aggressive scenario. At the same time, some other publishers with little exposure to China will be virtually unaffected.

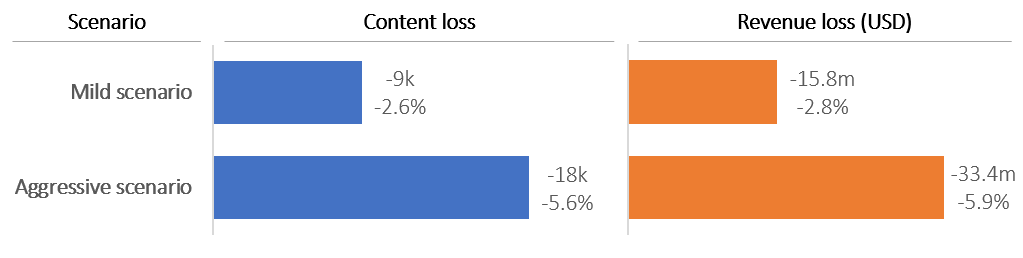

The impact will be felt more quickly and fully in the fully Open Access APC industry (Figure 5). This is because (a) Open Access revenue is proportional to the volume of content and is realized a few months after the submission of a paper, (b) Open Access journals have been drawing a higher proportion of their content from China (Figure 2), and (c) the new policy is likely to affect such journals the most. Overall, the APC industry is expected to lose up to $33m (assuming DOAJ prices in USD and no discounts), equivalent to 5.6% of its content and 5.9% of its revenue. Three top-10 APC publishers are expected to lose more than 10% of their revenue in the aggressive scenario.

What comes next for publishers

It will not be long before the impact of the policy becomes tangible. Publishers may see a drop in submissions within months, and the public will see the impact on published papers before the end of 2020.

Aside of the immediate impact, the policy hints on the strategic intent of a Chinese administration that wishes to have more control over the distribution of scholarly information. This will be a long-term game for international publishers who need to build strategies in response. They may seek to contribute to the development of domestic, high quality journals or try influence the development of future policy. In any case, they cannot afford to stay idle.

Discussion

8 Thoughts on "Guest Post – Quantifying the Impact of the New Chinese Policy"

dear Christos,

great contribution! Many thanks for your attempt to quantify the impact of these Chinese policies for the international publishing industry. You put numbers (yet best guesses, I believe) to expectations in the market(s). (see also my post on TSK of Nov. 19) !

I fully agree with your statement that establishing an alternative to the currently used metrics SCI / JIF ect is not easy to do. Time will tell, but all those researchers (international as well as China based) who are used to the current metrics and evaluation procedures are more likely to resist to new methods of evaluation than – say – the upcoming generation of academics. The yet (young-) generation of scholars may be more open to new measures for their own research-evaluation and thus new metrics (Chinese or international ones), as well as they may fancy new formats of scholarly communication going with these metrics. One way or the other. For the established international publishers it is clear that their future strategies will have to address these distinct Chinese needs and demands carefully!

best wishes, Matthias Wahls, The Netherlands.

Hi Matthias, thank you for reading through the post. I am glad you found it interesting.

You are right, the numbers are best guesses. I tried to cast a wide net in order to give a sense of what might happen next. I think we will have actual numbers before year-end. Time will tell!

Christos

I’ll preface my comment acknowledging four or five of my favorite colleagues being Asian, but I’m not bothered much if Chines scholars may become less prolific. The most disturbing trend to me has been the (occasional) appropriation without reference of very well-known seminal theories in my field by an Asian scholar who then becomes the exclusive source cited by others, often Asians, using that purloined theory. I do a lot of reviewing and frequently call out the idea theft.

Dear Christos, wonderful quantifying analyses! As a China-based journal publisher for many years, I completely agree with your point “researchers will still want to publish in the most impactful, most visible journals, which typically are indexed in SCIE”. In any sense, Chinese scientists still need to publish, no matter to be rewarded or not, in particular for senior scientists. The newly-released (not “new”) Chinese policies will have some influences: 1) making hard the lives of predatory OA journals; 2) forcing China-based English journals, 550 totally now, to seek ways to be well developed with more international visibility, mostly via partnering with international publishers, accounting for 80%+; 3) encouraging more China-based English journals to be launched, most of which will also very likely partner with international publishers to seek great international visibility; 4) hopefully, nurturing some local Chinese publishers to stand out, competing with international publishers. All these influences are very positive for both Chinese and international journal publishing industries, I would say

Hello Charlie, thank you for reading and commenting. I fully agree with your points. It’s not all doom and gloom for international publishers. There are opportunities here for those that can think and act strategically.

Christos

“…setting up an editorially rigorous and accurate index such as SCIE is complex and laborious. The Chinese administration may be able to achieve such a feat through trial, error, and considerable investment, but it is unlikely that it can do that within the next 2-3 years.”

One thing we’ve learnt time and again in recent years: never underestimate the Chinese ability to get things done!

Christos,

This is an interesting analysis of potential scenarios for paper decline from China based on current policy announcements. It is however based on a number of assumptions: that the deprecation of SCI and JIF, the use of blacklists and the “China first” publication policy will lead to submission declines. I am not sure the effects will be quite so clear as modeled. As I commented in a post responding to Tao’s original piece in SK on the policies, and indeed as you say, SCI and JIF are signifers of underlying journal brand quality as perceived by active researchers, and the attribution of value is independent of a separate metric or score. It is also the case that while officially SCI metrics will not be used I suspect that people will still have an eye on them as an aid to self-assessment of the value of a title. (And this is not a move away from metrics per se as a Chinese SCI is an objective of MoST and ISTIC.) The move to quality over quantity is happening in many other places too, but we are not seeing noticeable reductions in submissions as a result. This is because the driving force for any investigator is to announce what they are doing: you cannot be a researcher with publishing research. Data on the ratio of unique papers per annum per unique author have shown that productivity levels have fallen over the last 50 years to about 0.75. (See Mabe and Amin 2002 ASLIB Proc 54(3) 149-157 and Fanelli and Lariviere 2016 PLoS ONE 11(3): e0149504) This means that paper growth is directly related to author growth, and that the perception of salami publishing is just that, a perception. Co-authorships have grown but productivity per author has not.

I think the real question is the effect this might have on the domestic Chinese industry. Chinese policy has been driven by the need to crack down on fraud and questionable practices as well as an increasing nationalistic flavour coming from the top.

While I cannot be certain there will be no effect on paper growth from these policies I think if there is it will be much smaller than projected here.

Hello Michael, thank you for the truly insightful comment. One point I could have made clearer is that the manuscript loss refers to the current publishing establishment. Some of this loss will be gain for existing and new journals in China. So the analysis is partly about manuscripts getting re-channeled, not disappearing.

The analysis is also partly about manuscripts disappearing. We probably disagree on the point of ‘salami slicing’ (I never thought I would write such a sentence, but there we go). The papers you have shared are suggesting that this practice either always existed or never. My experience on the ground is that salami slicing is/was happening in China. If you had offered me double the exposure (or even less than that) for slicing this article in two, I would have considered it for a moment. People react to incentives, and if analysis is not capturing that, it does not mean it is not happening.

We will know in a few months, although something tells me that it will be hard to tell apart the impact the impact of the policy from the impact of COVID-19. Any suggestions as to how to model that are most welcome 🙂

Christos