While it may seem like disseminating scholarly communications is simple and straightforward, every provider of content and services does things a little differently. Each member of our community may follow standards for things like metadata or persistent identifiers, however, we develop our own unique approaches to the art and science of publishing. Peer review workflows vary, journal platforms are not identical, and ebooks can vary in form and function. Why is that?

Ultimately, how we design publications and deliver products or services reflects who we are and who we (think we) are serving. Organizations send clear messages (sometimes subtle, sometimes explicit) when they choose to implement accessible publishing workflows, or not; seek out feedback from diverse communities, or not; and design for the most privileged, well-funded users, or not. How publishers and technology providers approach product R&D (research and development) determines if the results are inclusive and welcoming, or exclusionary and limiting.

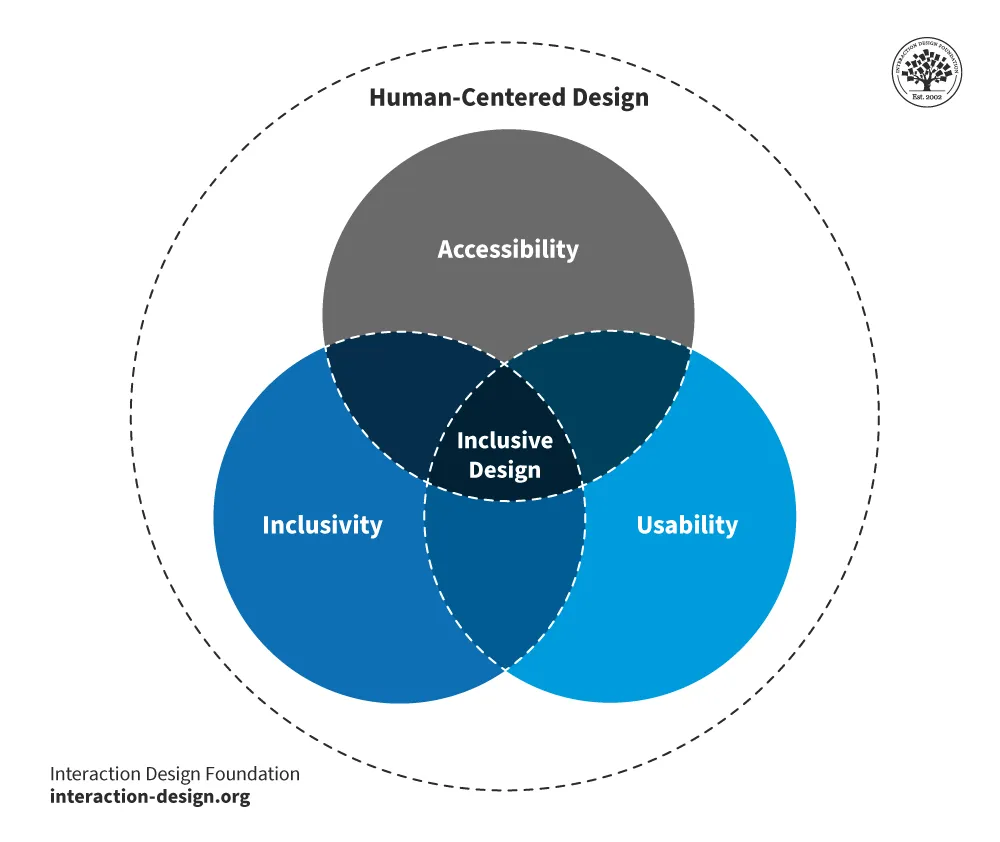

With each development cycle funded or new feature planned, we have the opportunity to adopt more human-centric methods and disrupt cycles of prejudice and privilege. Human-centered design means setting aside our assumptions and preferences to make room for an understanding of how our customers, communities, and users experience our offerings. Inclusive design means we choose to not perpetuate a “Mismatch” between end-user needs and the affordances, capacity, or tools for meeting those needs.

This approach starts by acknowledging the diverse information experiences of our customers and their end-users. Everyone who visits your site or reads your publications brings unique worldviews and past experiences, which shape how they encounter your products and services. Providers in our industry are not the average user, no matter what we might have in common with the librarians, faculty, or funders we partner with. Therefore, we cannot assume that, if we can complete a task or understand a feature, everyone else should, too.

So, what is the answer for our industry? How do we turn human-centered principles into an actionable plan that will produce more inclusive publishing products and scholarly communications services? Here are four strategies that anyone can adopt today and integrate into routine development projects:

- Don’t assume, ask!

At every touchpoint with our customers and their users, we have an opportunity to learn about their needs and pain points. Engage in open-minded conversation in those moments, to better understand their experiences and ask what they need to be successful. Ask academic librarians to introduce you to someone in their disability services office, or corporate clients can connect you to someone in their human resources department, to learn more about diverse users’ needs in their organization. Or, reach out to groups like the National Association of Disabled Staff Network. While we can benefit from established rubrics like WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) and COPE (Committee on Publishing Ethics) standards, we also should not assume we know what accommodations are required for all use cases. Approach these groups as experts we can learn from, as employing inclusive design is about doing the right thing for the health of our community and everyone involved — it’s not about feeling sorry for anyone or doing them favors.

- Diversify your target users

Creating more inclusive products allows us to widen our lens of who is considered a target customer or user. One way to do this is with diverse user personas, a common tool in website design and information architecture. If we are not careful, personas can be reductionist, reinforce prejudice, or perpetuate a focus on dominant, privileged experiences. Profiles of target users should consider their potential language barriers, physical limitations, and cognitive dysfunctions. Personas can be developed for people with autism, color blindness, cerebral palsy, fibromyalgia, hearing impairments, glaucoma, macular degeneration, and more. Users operate on a diverse spectrum of functional needs and interactive capabilities, and conditions can be permanent, temporary, or situational.

- Consider function over identity

In the course of customer focus groups, author surveys, or end-user testing of new designs, focus on the “jobs to be done,” rather than characteristics like race, gender, religion, etc. Inclusive R&D defines the specific functional needs of target users and what mobility, cognitive, auditory, or visual interactions are required to achieve their primary tasks. Screen potential participants for market or user research with functional questions, not identity questions. While tallying demographics can be a tempting way to measure inclusivity, facilitating the widest possible range of user actions and functional success leads to the usage and engagement that ultimately translates into higher sales, citations, and other metrics of strong publishing programs.

- Make accessibility ordinary

For many organizations in our community, improving online platforms’ accessibility compliance has been the focus of high-dollar auditing and content upgrade projects (in particular with the requirements of the European Accessibility Act). The alternative is to make accessibility compliance part of ordinary cycles of content production, website development, and platform enhancements. These can be programmatic checks, like those available in Microsoft Word applications and automated evaluation tools, as well as first-hand validation from customers and users themselves. Some may grimace at the thought of adding accessibility checks into every workflow, but it beats costly remediation of backlists or, worse, incurring legal fees or regulatory fines if users with disabilities (or their advocates) press charges against your organization.

The fact is, investing in inclusive design helps everyone your organization serves — and can open up new markets and revenue streams. Champions of inclusive design are often heard saying: “Solve for one, extend to many,” meaning, a feature or affordance that is assistive for some will likely be valuable for everyone. Just like cutting curbs for disabled veterans also benefits parents with strollers and travelers with suitcases, inclusive scholarly communications are rich with win-win features. For example, enriching metadata for screen readers also enables a richer audio experience for all sorts of readers.

To make inclusivity the rule of thumb, rather than an off-hand gesture, organizations in our community must integrate human-centric principles into business-as-usual publishing and design practices. If we take small, incremental steps toward inclusive publishing and services, giving everyone an equal chance at participating in scholarly communications will become the status quo and not an afterthought.

Acknowledgments: In addition to the experts cited within this post, the author would like to extend special thanks to Simon Holt, Accessible Publishing and Disability Inclusion Champion at Elsevier, for generously sharing his insights and recommendations for strategic and tactical approaches to accessibility compliance.