Transformative agreements have emerged as a highly effective tool in the transition to open access publishing. These agreements have enabled institutions and nations to shift their research outputs toward open access. They have also expanded the open access footprints of publishers. Librarians and publishers have relatively quickly established contractual norms and practices that bundle reading and publishing and streamline workflows for authors to be authorized for publishing coverage. Likewise, pure publish agreements have established similar workflows for open access publishing under institutional contracts and begun shifting gold journals from one-off payments for each article. As transformative agreements mature, they offer an ideal platform for addressing broader issues beyond access — most importantly, research integrity.

This essay argues that next-generation transformative agreements should integrate research integrity considerations, formalizing partnerships to uphold the quality and ethical standards of scholarly outputs.

Transformative agreements can be more than just tools to enable open access publishing and access to paywalled context. They can also serve as mechanisms for institutional accountability in upholding ethical research standards. By including provisions related to research integrity — such as designated contacts for misconduct investigations, mutual commitments to ethical guidelines, and penalties for non-compliance — these agreements can become instruments for establishing publisher-institutional partnerships based on shared ethical commitments and fostering a more responsible and resilient scholarly publishing environment. This collaborative approach would ensure that both publishers and institutions play an active role in safeguarding research integrity.

Publishers Need Institutions as Investigatory Partners

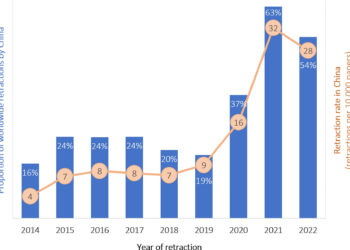

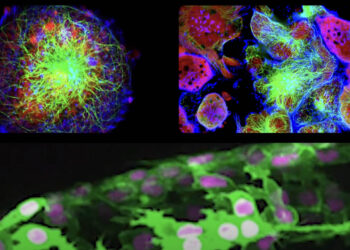

Publishers are facing significant challenges related to research integrity and maintaining the quality of the scholarly record. In recent years, the rise in incidents of paper mill submissions, data falsification, and other forms of misconduct has increased pressure on publishers to identify and reject problematic manuscripts. The advanced screening tools that publishers have implemented, such as plagiarism detection software, author verification checks, and artificial intelligence-driven fraud detection, are valuable but not foolproof. Integrity issues may not be detected until post-publication, perhaps triggered by third-party complaints or after unethical patterns emerge over time.

To address these challenges, publishers increasingly need universities and research institutes as partners in investigating and addressing integrity issues. When ethical concerns arise, allegations of data manipulation, plagiarism, or authorship disputes often require deeper scrutiny than publishers alone can provide. As the home institutions of the authors in question, universities and research institutes have access to critical resources, such as raw data, funding disclosures, and institutional policies, all of which are essential for thorough investigations. When publishers flag potential misconduct, they are reliant upon institutions to investigate and resolve the issue in a timely and comprehensive manner. Without institutional cooperation, investigations are delayed, or completely stalled, leaving ethical concerns unresolved and unaddressed.

A significant challenge for publishers in this process is establishing reliable communication channels with institutions and a collaborative investigatory relationship. Not all institutions have a dedicated research integrity office, and even those that do may not be responsive to publishers’ inquiries. As a result, publishers sometimes struggle to find the appropriate contact point to initiate an investigation or receive updates. Transformative agreements offer a mechanism for addressing these challenges.

Contractual Commitment to Research Integrity

Because transformative agreements establish contractual terms for reading paywalled content, the reading side of these agreements is relatively mature. License agreements for digital content have been iterated over decades to address a wide range of considerations, including identifying entitled reader groups, establishing authentication and authorization protocols, and detailing responsibilities in case of piracy or privacy breaches. In contrast, the publishing side of transformative agreements is relatively young and currently focuses, understandably, on the central concerns for entitling authors to publishing coverage and related payment terms and workflows.

As transformative agreements mature, they can be strategically leveraged to address additional publishing-related responsibilities, including safeguarding research integrity. Specifically, publishers could incorporate clauses that require the institution to identify a designated contact to handle research integrity investigations, just as they would for access-related matters like login issues or security breaches. Likewise, institutions may wish to negotiate for parallel requirements from publishers.

Publishers and academic institutions already collaborate on technical matters related to access; extending this collaboration to include research ethics is a natural next step. For example, in cases of suspected misconduct or ethical concerns related to publications, publishers could rely on designated university personnel to respond and engage with these issues directly. Additional contractual clauses could include agreed-upon investigatory procedures, such as a mutual commitment to follow COPE’s guideline on “Cooperation between research institutions and journals on research integrity and publication misconduct cases,” and penalties for failure to respond.

Institutionalizing research integrity commitments in a transformative agreement would not only benefit the publisher by providing clear points of contact and faster resolutions but would also strengthen an institution’s own commitment to fostering a culture of ethical research. Institutions would be more likely to invest in training and resources to address research integrity concerns proactively if they were contractually obligated to do so through their publishing agreements.

A Collaborative Approach to Safeguarding Research Integrity

Such provisions would also foster a closer working relationship between publishers and institutions. When a concern arises regarding the integrity of a particular publication, a publisher can then quickly turn to the institution’s designated research integrity team for assistance with resolution. This partnership would help streamline responses and ensure that ethical concerns are addressed efficiently and consistently and would ensure that institutions are active participants in maintaining the ethical standards of the research they produce and rely on publishers to disseminate.

If an institution is unwilling to identify a research integrity officer or commit to timely investigation, a publisher may wish to take this into consideration as it decides whether to strike a transformative agreement and, with or without a transformative agreement, as it reviews manuscripts from researchers affiliated with that institution.

Conclusion

As transformative agreements evolve, they present a strategic opportunity to address the growing concerns surrounding research misconduct. By clearly defining roles and responsibilities for publishers and institutions, these agreements can ensure that ethical issues are handled swiftly and effectively. In a research landscape increasingly plagued by challenges such as data falsification, plagiarism, and fraudulent publications, transformative agreements can serve not only as enablers of open access but also as cornerstones of a more ethical scholarly ecosystem.

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Leveraging Transformative Agreements for Research Integrity"

Thank you, Lisa, for highlighting the potential of transformative and open access publishing agreements as they continue to evolve. Curtis Brundy and Joel Thornton offered some practical ideas on how expectations for research–or, rather–publishing integrity could be integrated into open access agreements in their UKSG Insights article (https://doi.org/10.1629/uksg.659). Generating accountability for publishing integrity will be a key focus of discussions at the 17th Berlin Open Access conference next February.

When I was helping at Elsevier on publishing integrity issues, the difficulty in identifying folks to communicate with at universities and research institutions (not to mention funders) was incredibly frustrating— for the majority of these organizations (a minority had clear processes and contact points). Totally agree Lisa that this is a critical need— and I would suggest any agreement or working document could address these issues, not just TAs (although TAs are very common now). I am sure however that publishers could also do a better job of identifying process and contacts. I know that when I was involved at Elsevier, I would often hear about complaints being directed to the journal editor, and in some cases those editors not being aware of or not very interested in these issues. We always addressed these issues in journal editor meetings and conferences, and tried to put information on handling issues on internal and external web sites, but one can always do more to improve clarity and communication. All parties need to step up here…

Lisa this was excellent. Well done.

I’ll also add/argue that there are opportunities here for publisher coalitions to collaborate on these issues (think of Purpose Led Publishing in physics), especially to detect field specific nuance in publishing ethics. But I do think the university should be the front lines on partnering with publishers to lead this charge. I do worry about those smaller universities who may not have these kinds of offices, but it’s going to be a necessity for a research ethics officer at any university – large or small – sooner rather than later, so get it up and running now proactively rather than reactively when the problem strikes.

Thanks, Lisa. At face value, this sounds like a good idea but as your link to the ESAC website points out, “We can observe that more than 75% of any given country’s research article output is published in the journals of around 20 publishers, with the majority of articles likely to be concentrated in the journals of 3-4 publishers.” You are right, “transformative agreements have emerged as highly effective tools” for these same 3-4 publishers but let’s call it is what it is – a business model to enlarge their big deals, maintain their stranglehold on library budgets, and further commercialize scholarly research in the name of a bunch (not all) of very good journals and open access. With this kind of market dominance, profitability and binding annual contributions from academic libraries, a guarantee of research integrity from these 3-4 publishers should already be happenning, no?

Springer’s successful IPO clearly demonstrates investor confidence in Transformative Agreements that lock up both subscription revenue AND “APC Funding” in multi-year agreements with inflationary price increases hidden in confidentiality clauses. You mention that “libraries and publishers have relatively quickly established contractual norms and practices that bundle reading and publishing…” I’d argue that without research integrity clauses already included at these price points, it was too quick and it is not just libraries and authors who are paying the price.

I think it is worth remembering that librarians first asked for transformative agreements and publishers resisted offering them for quite some time. (I can still see one library negotiator animatedly explaining to me at a cafe in Denver during a library conference how ridiculous it was that publishers would not offer her institution a transformative agreement when they claimed to be market-driven but here the market was demanding and they were not responding!) Even if they have now embraced them, it took librarian persistence and advocacy to get them past the initial refusal. And, it would be a great disservice to the many not-for-profit and smaller publishers who have put a great deal of time and effort into transformative agreements to only give credit to the largest 3-4 publishers for this change.

Anyway … if it is the case that publishers should have demanded research integrity clauses in these contracts before now, there is no better time than the present for them to start requiring institutions/libraries to provide contact information and commit to working with them on investigations.

I had the pleasure of attending UKSG last spring and this was not at all how many of those librarians saw TAs. Session after session blamed the publishers for forcing TAs on them. They were being buried under the logistics of implementing a national TA program. There was no central accounting system so they were all using Excel spreadsheets, hunting down funds, having funds taken from one library when another ran out, needing to negotiate who pays when an author moves from one institution to another, etc. In some sessions, the librarians stated that they could not handle any more TAs without additional staff. Maybe it was just the JISC implementation that was problematic, but their experience did not seem to reflect what you explained here.

I’d be interested in how exactly this “forcing upon” by the publishers could be happening. Are publishers literally refusing to offer subscription contracts if a library won’t sign on to a TA? Please be in touch folks if that is the case because I want to write about that here in the Kitchen!

Having said that, even if it is the case now, it doesn’t change the fact of how TAs got started.

If I may, I interpret “forcing upon” as compelling sales tactics from TA publishers against a backdrop of a library budget that is not keeping pace with inflationary increases from commercial publisher agreements. It is real.

Let’s unpack what is happening here. You can find a TA license with most of the Academic Big Six (those being sued in the anti-trust lawsuit) on some consortium websites.

Generally speaking, a library has historical subscription spend and a historical average amount of APC funding with a commercial publisher. Add them together and subtract X% and the sales rep can offer this as a “savings” to a library packaged as a “bigger big deal” or TA under a new multi-year agreement with annual/compounded inflationary price increases.

Now the library has a compelling offer that “saves” money and streamlines OA publishing for your faculty – at least until the APC cap is achieved. What happens after the APC is achieved? You can pay more to the publisher, paywall the article or publish elsewhere. I spoke to a library that hit their cap in August! Now if they want to publish with this commercial publisher, they have to manage this false choice for every new article for the remainder of the year!

While no one is forcing a library to accept these terms, the offer is smart business for publishers and compelling for libraries at face value – certainly in year one and two.

But what looks good, are now becoming “Bigger Big Deals” (as reported by C&E) with academic libraries in a model that will take 70+ years to transform (JISC).

No wonder it takes that long – the model directs faculty to these publishers and when the cap it hit you either pay the APCs, paywall the article or move to another publisher where it isn’t so easy. What percentage of these articles are then paywalled? Would a high number surprise anyone?

It’s all well and good from where the model originated, but now there are real world impacts that need to be reported.

Yes, SK, please write about this!

Hi Steve, Appreciate your thoughts. And, glad to see where we have common ground: “While no one is forcing a library to accept these terms, the offer is smart business for publishers and compelling for libraries at face value – certainly in year one and two.” That is also my point. Libraries are assessing the offers and making a business decision of whether to sign. It may turn out to be a bad decision inn retrospect or have consequences that some find undesirable but neither of those mean the the TA was forced upon the library.

I remain interested if publishers are refusing subscription-only agreements. Particularly as I have written about cases in which libraries refused subscription-only agreements as a negotiating strategy for achieving the TA they wanted. If any publishers are adopting the tactic of refusing subscription-only agreements, that would be of great interest and I again invite people to get in touch with me if that is happening.

Thanks, Lisa. I’ll end my commentary with this – bottom line – these agrements from large commercial publishers are borderline predatory using the idea of transformation to open access to secure more annual marketshare when it will take 70 years to transform.

Let’s use this forum to raise awareness that despite where TA’s originated and the semantics around the commercial behavior to libraries, we talk about and report on the impacts of TAs on our industry:

– how TAs are strengthening the power dynamic for large commercial publishers

– the devastating effect TAs have on small publishers and the scholarly monograph

– how these agreements widen the inequities among the research community

– how there is little transparency and terms continue to remain hidden behind confidentiality causes

– how TAs come at an increased cost for libraries and authors

It is not too late.

I researched one of these commercial publisher and they launched 33 new start open access journals in 2023 and 63 new start open journals in 2024. Starting a new journal is incredibly costly and very difficult. Here are a mind-boggling 96 new OA journals for your faculty to publish their articles.

My takeaway from this development is that JISC’s estimate of 70 years is too conservative. Hedge enough new journals while you sign libraries to TAs and these hybrid journals will never become fully open and your historical subscription spend will retain its purpose.

A key point is that all scholarly players have a role to play wrt integrity issues. Publishers are generally good (or getting better ) at systematic checks for possible plagiarism, manipulated images, and the like. However they don’t have capacity to determine what happened at a particular lab, or how to evaluate competing claims re authorship. Publishers may suspect that a junior researcher was not the only person involved in possible illicit actions— such matters are really in the purview of the institution that supervises and employs the researchers.

I am not sure anyone should take credit. Transformative agreements are “Bigger Big Deals,” as reported in the C&E Scholarly Journals Market Trend Report 2024 (C&E, 2024, p.42). My concern is that the more we normalize TAs, the more the unintended consequences weaken our industry through the entrenchment of corporate publishers with academic library budgets, the further consolidation of independent societies with larger publishers (C&E, 2024, p.42), and how the race to the bottom with aggregators for what resources are left with academic libraries are driving out or putting financial stress on small, independent and not-for-profit publishers without a platform.

In the last two months, these consequences have been felt with two stark realities: On one hand, Springer launched its IPO (10/4), and on another, one university press prominent in OA announced it was being acquired due to a lack of support from the university (Central European – 8/1), the provost saved another press after a public backlash (Washington State -8/9), another is closing (Cincinnati—10/18), and a fourth one is currently seeking funding sources as its institution will no longer support it in 2025 (Confidential—10/7). It is all connected.

One could question what’s the value added of those publishers, if they’re unable to perform functions essential to their products and they need to force their customers to perform them instead. The risk of such investigations is part of the cost of doing business (especially when you run megajournals with tens of thousands of papers per year) and publishers should cover it. In some disciplines, like medicine, established mechanisms exist to appoint panels of reviewers for various needs: if they care, publishers could just start purchasing such services. Of course it wouldn’t come cheap. As the costs can be significant and potentially higher than the assets of a publisher, a pooled “insurance” may be in order.

I struggle with the idea that journals are the only stakeholders with any responsibility for upholding ethical behavior in the research community. Don’t universities have at least some role to play in ensuring their employees are not committing fraud? Further, journals can only catch that fraud after it has been committed, after the funder’s money has been wasted, and after the university’s reputation has been stained. Shouldn’t we be trying to stop fraudulent behavior earlier in the process, or are you okay with letting it happen and then demanding that journals clean it up?

No question that there are responsibilities across the ecosystem of scholarly communications. Not the least of which it is researcher’s responsibility to act ethically! Nonetheless, if publishers want to claim a value proposition of “the integrity of the scholarly record” … the they need to deliver on that using the various tools, incentives, etc. at their disposal.

I think the other big question re TA’s is their long term viability and suitability for both libraries paying for them and their wider institutions. This is certainly the case in the UK where both JISC and individual libraries are increasingly asking questions about the costs involved and whether they are really advancing Open Access in way and speed perhaps originally envsioned.

Thank you for your insightful piece, Lisa. I think you have a very good point and there is clearly an opportunity in TAs to align our strategies for a shared goal that both publishers and institutions share in the upholding of high research practice standards.

TAs also offer an opportunity for institutions and publishers to support Open Science practices that go beyond publishing the article OA (CCBY)— publishers can play a role in ensuring researchers deposit code and data in public repositories, create dedicated protocols and share them openly and deposit preprints. These goals are often aligned with those of institutions, so there is again an opportunity there to align goals in ways that make supporting Open Science easy, supported and free for authors.

I don’t understand the connection between TAs and the very good idea that there be an easily identifiable institutional contact point for processing integrity issues.

If librarians want to help address this issue, they could curate a list of contact points for each ROR (or Ringgold) institution. That way there is no burden on authors to supply this information during submission since it can be automatically inferred from their institutional affiliation. Same goes for funders. Maybe such lists already exist? Is this too practical a suggestion?

Hi Richard, I am not observing that librarians want to help with this issue (though hopefully they do) but rather than publishers are not consistently able to find institutional contacts and so publishers could use the TA process to get a contact, just as they also sometimes do to get an IT contact.

Hi Lisa,

Here in Canada, I’ve heard that some publishers no longer want to negotiate Read-only agreements with CRKN, only Read-and-Publish 🙁