Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Lettie Conrad and Avriel Licciardi. Lettie is a Scholarly Kitchen chef and Product Experience Architect at LibLynx. Avriel is a Publisher at Wiley, where she oversees a portfolio of 25 journals in the life sciences.

A diverse panel of researchers joined the 2024 New Directions seminar hosted earlier this month by SSP in Washington, DC. The closing event was designed to allow attendees to hear directly from researchers at different career stages and across varying academic disciplines about their first-hand publishing experiences. Students, faculty, and other researchers are the foundation of the scholarly publishing industry. They participate not only as authors, but also as reviewers, editors, and readers. They also wear many other hats that intersect with our industry; they are marketers of their work, managers of their teams and labs, funders for their research, and influencers within their research fields. This high level of involvement in the scholarly publishing community illustrates how essential it is to understand what researchers believe is important, what is valuable to them, and what is relevant to their careers.

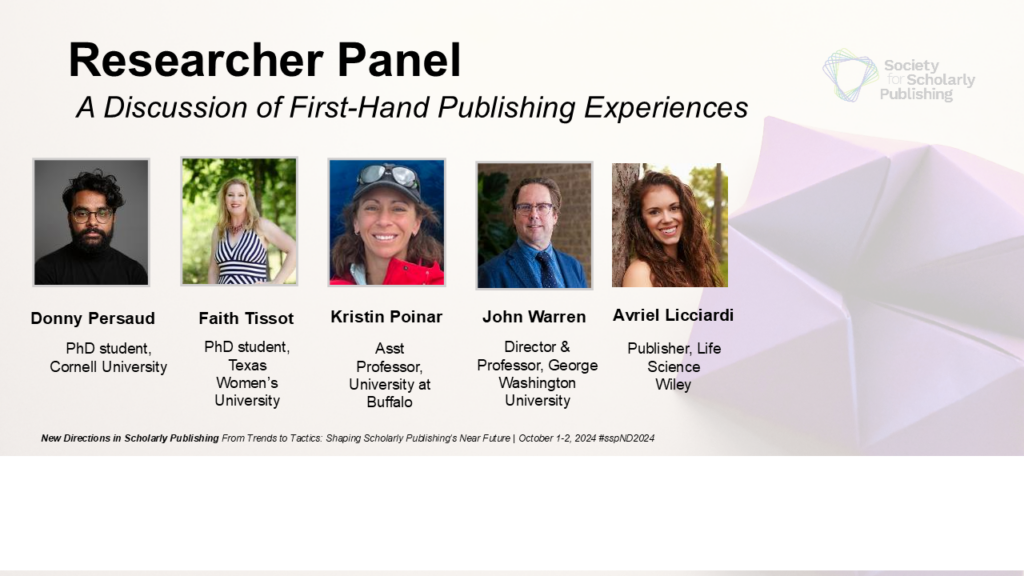

Our panel was made up of two early-career researchers, one mid-career academic, and one advanced researcher (with a specialty in publishing!):

- Donny Persaud: Doctoral student in Geography at Cornell University’s program for Science and Technology Studies

- Faith Tissot: Doctoral student in the Nursing Science program at Texas Women’s University

- Kristin Poinar: Assistant Professor in the Department of Geology at the University at Buffalo

- John Warren: Director and Associate Professor in the Publishing program at George Washington University

Rapid-fire ice breakers

While the group met before the seminar to discuss the event format and topics, the panelists agreed to kick off the session with rapid-fire questions that were previously unprepared. Keeping their answers short, the panel got things started with off-the-cuff responses to simple yes or no questions, designed to provide attendees a quick view into the scope of these researchers’ experiences.

- Do you post your research on preprint servers? Three panelists said “no, while one said “yes” to this first question.

- Are you currently aware of funding for publishing provided by your institution? Again, three said “no” and one “yes.”

- Should ChatGPT or other LLMs be listed as co-authors on published manuscripts? One panelist responded, “absolutely,” without hesitation. Two were flatly opposed to the idea. The fourth gave a mixed reply: “Listed as a co-author? Absolutely not. Acknowledged, perhaps, as use? Yes.”

- Do you think the publishing industry is trustworthy (scale of 1 to 5)? Ratings were mixed, from moderate to high trust, with scores of 3, 3, 4, and 5.

- If you could pick one reason for choosing a journal to publish your research, what would that singular reason be? This panel felt compelled to publish in journals they read and/or used in their work, as well as the relevance of the readership, aims and scopes, and affiliation with professional societies in their fields of study.

- What is one reason why you would choose not to publish in a journal you previously published in? All four panelists agreed that they would avoid submitting to a journal where they previously had poor publishing experiences, such as being too slow to return a review and decision or if the journal’s readership had declined.

Preferences and practices?

The panel went on to elaborate on the drivers for selecting a journal for manuscript submission, reflecting on how they determine the relevance of a journal to their research agenda and which venues allow them to highlight different aspects of their work (e.g., methodology or presentations). The primary motivation for all panelists’ journal selections is how well the publication aligns with their goals for reaching specific disciplinary communities, where the Impact Factor was a lower consideration. Secondary considerations included open-access (OA) fees and word/page limits.

Kristin Poinar voiced her preference to publish in professional/scholarly society publications. She also revealed that if a large commercial publisher publishes society-owned journals, this does not influence her journal selection. As long as her work remains in a society journal, she is satisfied. Regardless of reputation or quality, if OA fees are too high, however, many members of this panel of researchers would likely select another venue for their submission.

Are publishers your partners?

A question from the audience prompted one of the most insightful moments of this panel: What would you like to see or hear from publishers after your work has run in a journal? How would you like publishers to measure and report on the impact of your contributions to their journals?

Not surprisingly, John Warren had already spent considerable time pondering questions like these; however, this was a new thought for the other three panelists. Poinar said, “I’ve never thought of that. Once the article is published that has always seemed like the end to me,” except for monitoring citations. Faith Tissot mentioned, “I guess I’ve never really seen that as something that anyone could control.”

Once they pondered this opportunity, the panelists were eager to learn what publishers could do to market their work and report on usage, citations, etc. Poinar said that metrics “…would be quite valuable, especially because I am working on something that’s really policy-engaged right now,” where the ability to demonstrate “real-world impact would be pretty motivating.”

Appetite for new journals?

Another attendee asked the panel if they would consider publishing in a brand new journal — and, if they would, what would they be looking for? Would their criteria for a new journal be different from an established journal? Poinar said she would evaluate if there were specific incentives or benefits of a new journal, as her experience favored more well-known titles with a proven track record for reaching their target audiences. Many panelists noted that mentors and supervisors pointed them toward reputable titles. However, Warren noted that newer journals might be able to reach a specific niche readership that larger, more general titles may miss.

Thoughts on predatory journals?

Another attendee wondered: Have any of the panelists received solicitations from suspicious or predatory journals? How did you identify the red flags? Most panelists felt predatory journals were easy to identify because of their email solicitations for either submitting and/or reviewing a paper. Poinar commented, “They’re easy to identify in my field,” because there are about a dozen well-known titles in her area of study and anything not on that list is not reputable.

This rule of thumb doesn’t always prove true, however, as Poinar told a story of receiving an invitation to review a paper for a journal she was not familiar with; however, after a bit of reading, she found it to be a legitimate journal and agreed to the review. Tissot and Persaud also had experiences with “spam” emails from journals they did not recognize. Persaud said he might investigate on his own (is the sender using a gmail.com address?) or ask a supervisor for guidance (some departments provide guidelines for determining the value or reputation of a publication).

Do you share your research data?

Beyond traditional journal articles and book chapters, another attendee wanted to learn if the panelists were in the habit of depositing their raw data or research results into repositories or using other ways to share the underlying data. Warren spoke of his experience with open textbooks and opportunities to share non-traditional data, like qualitative research results.

Donny Persaud, who works with quantitative datasets, had some experience sharing sample data files in Github. When he uploaded larger datasets to their university repository, he found them to be more difficult, requiring an investment of time into formatting and curation of the data. He underscored the matter of incentives and said he would likely share his datasets if there were clear benefits or specific motivations.

Let’s talk about peer review!

Warren noted that the topic of peer review reminded him of “a quote attributed to Winston Churchill… that democracy is the worst form of government, except compared to all other forms of government.” He found peer review to be similar, in that the double-anonymous method is probably the worst, except when compared to the alternatives. Warren said it is important to experiment, “but I don’t think I’ve seen anything better than double anonymous.” He reflected that double anonymous reviews are the norm for humanities and social sciences. “I like not knowing who’s reading my work. And I like that they don’t know my name,” he reflected.

Poinar noted, reflecting on her experience with serving as a journal editor, that she could relate to discussions of “the Peer Review crisis” at the New Directions seminar — and she was hoping attendees would have suggested solutions. “It’s so hard to find peer reviewers who are qualified and who say yes, and who have the time,” she reflected. “And I’m part of that problem,” she laughed, noting that she often declined peer review invitations due to a lack of bandwidth. With audience input, the panel debated methods for inviting reviewers in small batches or casting a wide net with dozens or hundreds of invitations sent at once.

The panel discussed what qualifications they see as critical for conducting peer reviews. They collectively agreed that post-graduate training in a relevant field should be required, but there was some debate about whether reviewers should first have experience publishing as authors. The panel agreed that early-career researchers should be given a chance to serve as reviewers, both for their own professional development and to widen the pool of potential reviewers. Some panelists felt that early-career reviews should be balanced by one or two other reviews from more established experts.

Tissot shared how her doctoral program expects students to complete a formal competency in peer review, which includes a training session specific to publications in their field. Students in this program cannot begin work on their dissertation until they have satisfied the peer-review requirement for an academic journal. While peer review was not specifically required, Poinar reflected on her PhD program’s priority on publication and the high-impact dissemination of original research outputs.

Aren’t they going to talk about AI?

The use of AI-power tools in peer review was a natural segue to the topic of artificial intelligence. The panelists agreed they would not be comfortable with reviews entirely generated by AI, but many were not opposed to the use of AI at some stages of the review and publishing lifecycle, as long as humans were in the loop throughout. Warren reflected on the value of having his students edit or critique AI-generated essays and encouraged his students to experiment with AI tools so they are fully aware of the technological capabilities they offer.

Persaud shared his experience using AI tools for statistical analysis, but only after he completed his original analysis (to avoid being unduly influenced by AI-generated results). Tissot noted that her doctoral program strictly advises against the use of AI tools, in particular when training healthcare professionals, to ensure that students are learning independent critical thinking — for example, how to diagnose in direct engagement with patients and not relying on the use of computational solutions.

Closing thoughts

The conclusion of the panel returned to a final rapid-fire question asking the researchers to summarize in one word how they currently feel about publishing. Persaud responded, “optimistic.” Tissot said she felt “intimidated,” which Poinar said she could relate to at first. But, now she is “amped” about publishing — “it’s how we get the word out!” Warren closed by saying he felt publishing is “a stable landscape of continuous change.”

We want to thank our panel of researchers for sharing their experiences and making this conversation so engaging and enlightening. We hope these (and other) researchers will join us again for SSP’s New Directions seminar in 2025 and beyond, as learning directly from authors and reviewers enriches the work we do and the quality of our stewardship of the scholarly record. We encourage your questions and reactions in the comments below. Join the conversation!