Editor’s Note: Today’s piece is by Michael Rodriguez. Michael serves as Senior Strategist for Content and Scholarly Communication Initiatives at Lyrasis. The author thanks Anne Krakow, Danianne Mizzy, Teri Oaks Gallaway, and many other colleagues for sharing their insights.

Like the college closures discussed in my previous Scholarly Kitchen post, college consolidations have been a growing phenomenon in the United States for years. Standalone public institutions of higher education have merged into systems. Systems have merged or otherwise reorganized their component institutions with one another, while struggling private colleges are acquired by or merged into better-resourced institutions. These mergers have impacted dozens of colleges and tens of thousands of students in recent years. Also impacted are libraries and archives, as well as the library consortia and vendors that support them. While mergers can save struggling institutions and foster stronger student experiences in the long run, mergers are complex and their implications for scholarly content and services must be considered thoughtfully.

Overview of College Mergers

While the pace of closures and mergers has slowed in the latter half of 2024 (according to this running tallyfrom Higher Ed Dive), consolidation remains widespread in the Northeastern and Midwestern United States — regions with falling populations of traditional college-age students. Recently announced private-sector college mergers in Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York include Gannon University acquiring Ursuline College, Peirce College merging into Lackawanna College, and Marymount Manhattan College combining with Northeastern University. (Four of these six are Lyrasis members.) Meanwhile, public colleges and universities in Vermontand Connecticut have collapsed their standalone institutions into one multi-campus system, while the University of Maine established unified system accreditation of its seven institutions in 2020. Of the 26 campuses in the University of Wisconsin System two years ago, only 20 still endure today.

Small-scale mergers have been happening everywhere. Most recently, two Minnesota public collegesannounced that they were considering a merger. Bard College at Simon’s Rock closed, announcing plans to move to a new Hudson campus and warning that all 238 faculty and staff would have to reapply for their jobs. Experts are cautioning unsustainable colleges to seek a merger partner sooner rather than later, before their financial situations deteriorate.

These pressures are magnified by the fact that there are many different kinds of mergers. Some are essentially closures or complete repurposing of one campus, with immediate and existential implications for physical library spaces and collections, while other mergers bring together two or more institutions into a common administrative structure, with immediate implications for eresource licenses. Several flavors of each merger type exist, such as one institution becoming a wholly owned subsidiary of a different institution. Each of these merger types and flavors have varying implications, and the details, of course, depend on local contexts and circumstances.

As closures and mergers increased, literature on libraries navigating mergers of their parent institutions has started to emerge. A 2023 SCELC survey found that 14% of 51 SCELC member library directors who answered the survey thought it at least “somewhat probable” that their library would merge by 2033. Over half of US consortia directors who responded to the survey expected a merger to impact one or more of their members by 2033. Library leaders who have already gone through one merger use phrases like “flying blind” and “no blueprint.” Closing a College Library (ACRL, 2024) features case studies by library staff who have faced closures, but this coverage is just starting to make its way into the literature and into conferences.

As Anne Krakow, who led two mergers as library director at Saint Joseph’s University, observes, “For the first merger with the University of the Sciences, everyone was treading in unfamiliar water. With our second merger with Pennsylvania College of Health Sciences, I was able to put what I had learned into action to make that process much more seamless.” Danianne Mizzy, former Dean of Libraries at Montclair State University, which merged with Bloomfield College in 2023, commented that libraries have much to learn from the healthcare sector, which has dealt with analogous acquisitions, mergers, and closures of hospitals. “There are points for reflection and best practices we can adapt to prepare for all aspects,” said Mizzy, “not just collections.”

Implications for Library Collections

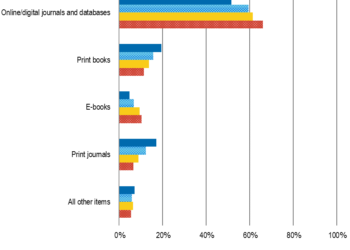

Mergers require intensive collection development and assessment, especially when campuses are shutting down or getting fully subsumed into surviving institutions. Physical collections may be reviewed and weeded against criteria such as duplication between libraries, and efforts must be made to standardize cataloging practices and classification systems (e.g., if one library uses Dewey Decimal Classification but the other uses Library of Congress Classification). Integrated library systems must be analyzed, data cleaned up and migrated, policies synced, and resource sharing between campuses set up. User authentication systems and networks must be merged into the main institution’s, though separate campus-level IP addresses and proxy servers might be kept to retain some campus-level subscriptions. Electronic resources must be evaluated and the merging library’s subscriptions canceled or renegotiated to enable institution-wide access. Nearly all institutions have acquired perpetual rights to some ebooks and streaming videos, or even journal backfiles or primary source archives, so the consolidated institution must decide which long-term rights are worth retaining and try to negotiate these rights with vendors.

For existing eresource subscriptions, many vendors permit institutions to fold in new students or campuses, without charging additional fees or else charging an adjusted subscription fee that factors in the new combined full-time equivalent (FTE) enrollment or other characteristics such as Carnegie Classification or the total number of catalog records. Some vendors consider usage as part of their re-pricing calculations, though usage is rarely the main metric. If both libraries undergoing the merger subscribe to the same product, vendors may try to maintain their revenue by tallying up both institutions’ fees and billing the combined fee to the surviving institution. In some cases, vendors treat the surviving institution as a new customer, resulting in the loss of any legacy discounts. The author knows of at least one library that had to re-purchase, at list price, all the ebooks that had been previously purchased by a recently acquired college, to ensure institution-wide access. Library leaders interviewed for this post recommended that libraries allocate plenty of time for vendor negotiations, commencing merger discussions with vendors as soon as possible but no later than 4-6 months prior to subscription renewal dates.

When colleges merge, the surviving institution may not be able to inherit the perpetual rights to electronic resources previously acquired by the merged institution. Many if not most vendor license agreements prohibit transferring or reassigning perpetual rights to a third party, or at least require the vendor’s permission to effect such a transfer. Additional complications emerge if the merged institution is affiliated with a hospital, as hospitals generally have distinct pricing structures (often based on number of beds), IP ranges, and credentialing. Other complications arise should the merger produce a single institution along with a wholly owned subsidiary that is still a legal third party. If an institution has obtained the right to reassign perpetual rights to eresources, do the eresources become tangible assets in bankruptcy? Can creditors or receiving institutions sell the eresources to pay off debts? Probably not — but there are few precedents.

Libraries should pay close attention to vendor license language referencing “geographic sites” or “authorized sites.” If pricing is based on FTE and/or Carnegie Classification, an institution that absorbs another institution may be covered under the surviving institution’s license agreement, assuming that the merger has not bumped up total enrollment into a higher tier. However, if a license requires the institution to list the geographic sites covered by the agreement, additional campuses probably are not automatically covered by the license. To avoid this scenario, licenses should state that the licensee will be treated as a singular institution inclusive of all campuses, branches, and locations and of all authorized users whether on campus or accessing electronic resources remotely, unless otherwise agreed in writing. This license language gives institutions the flexibility to maintain the separate status of law or medical schools as needed. In addition, to ensure that their expenses are predictable within a single budget period, libraries’ licenses should include language to the effect that the institution’s pricing will not change during the course of any annual or multiyear subscription period, regardless of changes to FTE or sites.

Mergers pose a lower risk to the scholarly record than closures do. Well-circulating, distinctive books and serials in library circulating collections are likely to be retained in a merger, unless the surviving institution has seriously limited capacity to absorb these collections. Swathes of the acquired collections could be deaccessioned if historical circulation is low according to the expectations of the receiving library, or if the physical materials, regardless of quality, support low-priority or discontinued programs. If the receiving library does not already participate in a shared program program or does not want to maintain potentially tens of thousands of items committed to long-term retention by the merged library, it could pull out of the shared print program, disrupting the program and increasing the retention burden on other participants.

Implications for Archives and Special Collections

Archives preserve and provide access to university records, such as meeting minutes, course catalogs, yearbooks, photos, personal papers, student newspapers, theses and dissertations, and more. In a merger, these materials come under the stewardship of the surviving institution. But what if the new owners see these materials as out of scope or too costly to accession and preserve? Institutions are not obligated to retain most archival collections unless governments, accreditors, or donor contracts require them to or unless retention of the archives is addressed in the agreements governing the merger in the first place. We can assume that most librarians and archivists would want to retain these materials, but capacity may constrain their choices.

Risks to retention are also significant for special collections comprising rare books, manuscripts, ephemera, and other distinctive materials. Post-merger, are receiving libraries duty-bound to maintain special collections, even if out of scope for its own collecting areas? Might receiving libraries prefer to offload certain collections by selling, gifting, or deaccessioning them? Many special collections and associated endowments are subject to legally binding agreements with various donors — agreements that may or may not carry over in a merger. Can donors veto the transfer of materials or funds? This seems possible, as a major donor reportedly torpedoed the acquisition of the University of the Arts by Temple University in fall 2024. Many concerns could be clarified in the merger paperwork, but it would be atypical for academic administrators to be well versed in the needs of their libraries. Library directors would need to advocate relentlessly to have their needs addressed during a merger, when matters of real estate, endowments, employment, and student welfare threaten to crowd out lower priorities like libraries.

Implications for Library Consortia and Systems

With a strong overarching sense of merger activities and needs, consortia and state systems are in pole position to help their library communities to develop these best practices. Smaller and less selective colleges that depend on tuition revenue and experience declining enrollment are most likely to merge in lieu of closure. Consortia and systems that include members that fit this profile should monitor developments among members that may lead to mergers and consider developing a set of services offered to merging members. For example, consortia might take the lead in negotiating rights reassignment and expanded access with vendors, provide technical expertise to migrate data between merging libraries’ systems, and develop robust consortial agreements to preserve and provide access to shared print and distinctive collections in the event of mergers. Consortia might also negotiate reassignment rights routinely into consortial license agreements long before mergers happen. Consortium-level or system-level stewardship agreements might help to ensure that library-published journals, open educational resources, special collections, and other essential resources are preserved in the event of member consolidation. Collective voices and actions carry more weight than individual libraries.

Implications for Vendors

Vendors incur few direct added costs due to customers’ mergers, apart from the time spent by vendor staff in corresponding with the customers and updating internal records. Nevertheless, vendors may experience customer mergers as a risk and potential loss of revenue, because two colleges paying separately for similar subscriptions pre-merger need only one subscription after merging. Hence, vendors with FTE-based pricing may require that consolidated institutions with higher combined enrollments pay annual or one-time “expansion fees” (as one publisher calls them) for institution-wide access. Similarly, vendors with pricing based on number of sites may ask a consolidated institution with two campuses to pay the same rate as its two predecessors combined, especially if both predecessors were active customers of the vendors’ products. By charging expansion fees during mergers, vendors may be able to generate additional revenue. However, sometimes vendors are unable to expand access or permit customers to reassign perpetual rights because they no longer have the rights to distribute certain content. In the author’s experience, most vendors are willing to reasonably accommodate library mergers.

Conclusion: We Need a Playbook

At present, library mergers are a mare’s nest. Libraries and vendors are coping with a dearth of standards or best practices to guide what happens to library collections in the event of mergers. Library leaders who have led mergers report feeling isolated, with little published guidance or research to consult and few knowledgeable peers to offer support. Similarly, many vendors lack consistent and comprehensive processes to support customers who are undergoing a merger.

The industry needs resources analogous to this guidance for student education records from the American Association of Collegiate Registrars and Admissions Officers (AACRAO) or this report on consolidation from the Healthcare Providers Service Organization (HPSO). In addition, the industry needs communities of practice, model license language, and clearly stated mutual expectations across the library, consortia, and vendor communities at scale. Addressing these priorities should in turn point our industry toward long-term strategies and opportunities.

Let’s continue the conversation in the comments.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Guest Post — College Mergers and the Implications for Libraries and Vendors"

This is not a substantive comment but as a former vendor and indeed a former librarian this strikes me as a very useful and thought through proposal

Anthony

Thank you, Anthony. It’s always a pleasure to hear from you! Your dual perspectives as former vendor and former librarian are invaluable. Once the library community has grappled with this problem space and defined its needs, the information industry as a whole will have to come together around solutions.

Very thoughtful piece, thank you for the contribution. I lost track of the number of questions after a dozen or so and don’t envy the library directors/deans tasked with a merger.

A question for thought: the politics of a merger in many cases could be rather peculiar and even intense. What would pressure to economize and streamline beyond the confines of the merger mean in these cases?

On the one hand, this isn’t necessarily the time to pursue such ends and yet there may be pressure to do so. And on the other, maybe it is the perfect time to do so even absent any pressure, especially at smaller, teaching-centric institutions that are merging. In such cases, a merger might be the perfect opportunity to explore new models of librarianship that depart, marginally or radically, from the traditional paradigm.

What’s the adage? “Never waste a crisis?” Periods of major change are opportunities to recommit to sustainability. Library investments in open access and open infrastructure, digital lending, and team- and function-based liaison models hold transformational potential. Much more of our work should be happening at the network level. But dealing with the operational aspects of a merger can be all-consuming, and staff and students at merged institutions often feel a painful loss of identity and autonomy and may be resistant to change that is not respectfully and collaboratively pursued. Notwithstanding these constraints, I agree that mergers are absolutely an occasion to rethink longstanding service models and paradigms.