Today’s post is co-authored by Roger C. Schonfeld and Christine Wolff-Eisenberg of Ithaka S+R.

Higher education institutions are suffering tremendously from the impacts of the pandemic. And, as one university president noted last week, if any colleges and universities are unable to reopen for residential instruction in the fall due to the pandemic’s continuing effects, the results will be “cataclysmic.” Even putting aside worst case scenarios, instability in the economy means that many higher education institutions will likely face reduced revenue this upcoming academic year. It is hard to see a scenario where academic libraries will be spared from the dynamics facing their parent institutions. Instead, many library leaders will face the dilemma of how best to cut back strategically.

A project team at Ithaka S+R conducted the most recent cycle of its large scale survey of academic library leaders at four-year colleges and universities in the US this fall, just weeks before the pandemic began its inexorable global circulation. Led by one of us (Christine Wolff-Eisenberg) and our colleague Jennifer Frederick, the team examined three broad topics: Leadership and Management; Roles and Services of the Library; and Collections and Licensing. Findings were just published and the complete report of findings is available freely online.

While much has changed since S+R fielded this survey, it also provides some of the most recent and comprehensive evidence for the directions that academic library leaders may take as part of strategic cutbacks. In today’s piece, we provide an overview of what lessons the scholarly communication and academic publishing sector can draw from the survey. Later this calendar year, we will be conducting a subsequent survey of academic library leaders to learn more about the approaches they have taken in the wake of the pandemic and the implications on their organizations.

Spending

Similar to previous cycles, directors are currently spending the majority (about two-thirds) of their materials budget on online journals and databases. While they spend the next highest share of their budget on print books, for the first time we’re seeing that the percentage of their budget spent on e-books has risen to nearly the same level as print books. These findings reflect the general trend of increased spending on all forms of electronic resources and decreased spending on all types of print resources.

What percentage of your library’s materials budget is spent on the following items? Percentages must add to 100%. Average percentages across all participants, by survey cycle.

The largest libraries are also the most digital in their spending. All subgroups by institution type differ in their proportion of materials budget spent on online journals and databases, with directors at doctoral universities spending the highest proportion and directors at baccalaureate colleges spending the lowest proportion (a difference of about 10 percentage points).

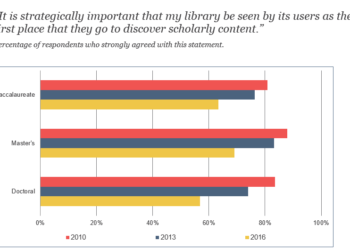

Value

Fewer respondents compared to the previous cycle believe that the value of electronic resources is rising faster than cost — this could possibly increase the likelihood of cancellations (more on this below). While about one-quarter of respondents believed the value of licensed e-resources resources was rising faster than cost in 2016, this share has fallen to just 14 percent in 2019.

Cancellations

For the first time, we asked library directors how likely they are to cancel one or more major journal packages in the next licensing cycle. Half of library directors say that they will likely cancel a major journal package in the next five years. We have not asked this question previously, so it is impossible to know that the figure has trended higher, but it certainly is a remarkably strong response.

Across the half of survey respondents that reported being “very” or “extremely” likely to make such a cancellation, we see that the proportion is quite consistent across institution type. That is, there are no significant differences between baccalaureate colleges, master’s institutions, and research universities.

However, cancellation exercises are clearly more complicated at doctoral institutions, not only because of the institutional scale, but also because far more stakeholder groups are likely to be involved and affected by the decision. While across all institution types–from baccalaureate colleges to research universities — the most important individuals with whom to discuss these decisions were librarians and faculty, respondents at research universities rated additional individuals and campus communities – -including senior academic leadership outside of the library, library staff, leaders at peer institutions or consortial members, and graduate students — as relatively more important compared to those at other institution types.

How important, if at all, is discussing the possibility of cancelling one or more major journal packages with each of the following? Percentages of respondents that selected “highly important” in 2019 by Carnegie Classification.

Transformative agreements

In recent years, transformative agreements have received lots of attention among scholarly publishers and here at the Scholarly Kitchen. But among US academic library leaders, it is a different story. A relatively small share of libraries plan on pivoting to transformative agreements to bundle publishing and subscription costs; only about 20 percent strongly agree it is a high priority to bundle open access publish fees with subscription costs. While there is no statistically significant difference across Carnegie Classification, a greater share of doctoral university respondents is interested in these transformative agreements compared to both master’s and baccalaureate college respondents; slightly more than 20 percent of doctoral respondents, slightly less than 20 percent of master’s institution respondents, and about 15 percent of baccalaureate college respondents strongly agree with the statement provided. While it is unsurprising that those at more teaching-focused institutions responded as they did, given their relative volume of research outputs, some readers may find it unexpected that directors at doctoral institutions are not more inclined towards these models of driving towards open access.

Looking Ahead

Supported by publishers and vendors, academic libraries have been leaders in the digital transformation of higher education institutions. Well before the pandemic, they developed collections that are more digital — from journals to archives to streaming media — and more accessible remotely, than most of the other academic offerings of the typical college or university. The successes, but also the limitations, of libraries’ digital transformation have become apparent in the disruptions that the pandemic has wrought over the past month across higher education.

One limitation is that many academic libraries have not shifted their staffing, facilities, and infrastructure with nearly as much alacrity as they have shifted their spending towards digital formats. To take a small but vivid example, one of the top unmet spending priorities of many of the respondents to the survey was facilities expansions and renovations, presumably in many cases to update facilities designed for collections storage and access to become spaces for research and learning. While it may be the case that “the primacy of print is past,” it is the rare case that technical and access services staffing or infrastructure has recognized this emergent reality.

To some extent, this is because libraries are about far more than this year’s acquisitions. Whereas many libraries have shifted their acquisitions budgets substantially towards digital collections (as we discussed above), they also have substantial print holdings which, even if comparatively ill utilized, remain vital scholarly and cultural records for which the libraries assume substantial stewardship responsibility. Recognizing this dilemma, it is little surprise to see some of the largest research libraries looking for how they might “manage the separate collections of the Big Ten as if they were a single shared collection” [PDF]. Just as collections digitization was seen as a generation-long proposition before Google brought mass digitization to academia, so libraries have seen the reorganization of print stewardship responsibilities as a gradual process prior to the pandemic.

But in light of the present disruptions — not only to residential education but also to academic library facilities — we have witnessed the collapse of print browsing, print circulation, and print interlibrary lending. One outright hero in this is HathiTrust, which has launched an Emergency Temporary Access Service to enable its members to make vast swathes of their unavailable print collections accessible digitally. While we hope these disruptions will soon end, it would be a real step backwards for readers and libraries alike if there were then no way to continue such a service on an ongoing basis.

Given the need to stay prepared for potential closures of physical library buildings in the upcoming academic year, we expect a resulting acceleration in digital collections and digitization at many libraries. And, given the cutbacks that they will be managing, it is hard not to anticipate accelerated efforts to bring their staff and infrastructure in line with increasingly digital service models. An unknown is whether the large research libraries accelerate the reorganization of their print stewardship responsibilities to enable greater operational efficiencies. But in North America, at least, it is even more difficult than ever to imagine “publish” universities electing to pay more through transformative agreements to move the sector to open access.

Now that so many academic libraries today are largely virtual organizations, leaders are beginning to work through these and other potential longer-term impacts of the present-day disruption. To elucidate the visions being pursued and the cutbacks being managed, we at Ithaka S+R plan to conduct and publish findings from a follow-up survey of academic library leaders later in 2020.

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Academic Libraries at a Pivotal Moment"

Is this when we will see the full digitization of libraries and universities. While there has been great effort made over the last couple of decades to move print online, it has too often been replicating the analog world. We still see business models that are based on one user at a time, book and journal formats that have not changed much in centuries and platforms that work like library shelfs with a traditional cart catalogue. In many ways libraries and information providers have listened too carefully to their buyer and users and in the words of Henry Ford created a faster horse (and thus not the car). Why do platforms not adopt to the skill and knowledge level of users based in their actions? A student who is new in the field nor seek nor have the same need for in depth results as a researcher who have been in the field for 20+ years. Still however most platforms provide a completely undifferentiated experience, though simple analysis of the users’ actions can provide a guide to on the fly optimize the experience (without need to invade anyone’s privacy).

It is time to end the last versions of business models that replicate a print models (or are linked to previous print spend) and fully embrace the many options for innovations around business models e.g. freemium, funder paid publications, enterprise access, micropayments, go fund me etc.

There are many great reasons why traditional books and journal formats persist, no less the tenure and promotion guidelines rewarding traditional formats and publication venues. A crisis should never be waisted and there is no better time to fully review these guidelines and enable a much broader set of options for sharing and disseminating scholarly information. A change in tenure and promotion guidelines to share research and learning objects, to value active participation in open science projects and broader societal sharing of insights in for example the form of podcasts, will in my view spark creativity. It could be the spur of that inspires and attracts new generations of students.

Where does streaming media fit in the expenditure survey? Is it part of the online database figure or is it in all other items? I ask because I suspect streaming media will play an increased role in online education, and I’m wondering how that might impact library budgets. I understand it was growing, but by how much, and how many HSS book purchases and journals, e and print, is it displacing and how much will it displace in the future?

Tony, our group is involved with researching this very topic at this time. More to come anon.

Fewer respondents compared to the previous cycle believe that the value of electronic resources is rising faster than cost — this could possibly increase the likelihood of cancellations

This is certainly possible, and it’s worth noting and bearing in mind. Also worth noting and bearing in mind, though, is the fact that cancellations are not necessarily driven by cost/benefit analysis at the journal or package level. In fact, in the current environment — and this has been true since long before COVID-19 came on the scene — I believe that cancellations are fare more often driven by simple exigency: let’s say I subscribe to 20 journals or packages, all of which offer high value relative to price, but I can no longer afford to pay for all of them. What do I do? Canceling journals and packages that don’t offer good value for money isn’t an option, because I cancelled all of those long ago. What I’m now forced to do is cancel journals that offer high value for money, and my strategy will be to try to identify those that will cause the least damage to my university’s ability to do its work.

Cost always trumps value. Cost always trumps value. Cost always trumps value.

Rick, can you say a little bit more about how you calculate “those that will cause the least damage to my university’s ability to do its work” in a way that is not ultimately a value metric? I’m wondering if we’re just saying the same thing using different language here!

Good question. Both are certainly value metrics, but only one of them is a value metric that speaks to the journal’s (or package’s) absolute value as a good.

Let me try to put it another way: for many years, when there was a more favorable balance of budget dollars and available purchases, librarians had the luxury of shopping. We would evaluate the expected value of a potential subscription, weight it against the cost, and make a purchase decision based on that evaluation.

Over the years, as both the number and the cost of available purchases have grown while our budgets have remained stagnant, we’ve gradually canceled subscriptions that are lower in value relative to cost. We’re now left with only high-value subscriptions. But the continued rise in prices and our still-stagnant budgets combine to force us to choose between them. So we’re canceling subscriptions — not because we’ve found them to offer low value relative to cost, but because we can’t pay the bills and have nothing but high-value subscriptions left to cancel.

So you’re right that we’re canceling based on an assessment of relative value to the campus (“Will it hurt more to cancel Journal X or Journal Y?”), but we’re not canceling based on an assessment that Journal X offers poor value relative to its cost. In other words, an increase in cancellations doesn’t necessarily reflect the belief that the cost of electronic resources is rising faster than their value, though it may; in the current environment, I think, cancellations more often reflect the fact that we can’t afford to keep those resources, even though we believe that their value has remained strong (or may even be rising, relative to cost).

There’s actually another important factor at work here, and that’s the desire to change the world. Not all who are canceling subscriptions (especially big deals) are doing so because they no longer believe that those subscriptions offer good value for money. Some of them are canceling because they believe the subscription model itself is fundamentally wrong, and they want it to be destroyed and replaced by a different model. Those who think this way tend to see the short-term pain of canceling high-value subscriptions as a price worth paying for the promise of a better future.