Editor’s Note: Today’s post is by Gwen Evans. Gwen has been the Executive Director of OhioLINK, the Ohio Library and Information Network, since October of 2012. She was previously Associate Professor and Coordinator of Library Information and Emerging Technology at Bowling Green State University. Evans has 18 years of experience working in libraries, including the John Crerar Science Library at the University of Chicago, Mt. Holyoke College Library, and Washtenaw Community College in Ann Arbor. She received her MS in Library and Information Science from the University of Illinois Urbana Champaign, and has a Masters in Cultural Anthropology from the University of Chicago, during which time she did two years of ethnographic research on the island of Flores, Indonesia.

As several recent announcements and initiatives have shown, Open Access (OA) negotiations between libraries and publishers are complex, in a constant state of flux, and provide little predictability — and OA models and negotiations within library consortia contain complexities all their own. One of the key questions library consortia have to ask themselves is, Are you a Publish or a Read library consortium, or somewhere in between? As Lisa Hinchliffe’s recent primer on transformative agreements notes, the implications of Publish and Read versus Read and Publish are different for different consortia.

The Read or Publish Composition Continuum

Library consortia can be characterized as “Read” consortia (not much publishing activity from institutionally affiliated researchers), “Publish” consortia (substantial publishing from institutional researchers) or somewhere on a continuum — and where a consortium or institution falls on the Read/Publish continuum will influence the kinds of deals that publishers are willing to offer them. As a practical matter, few institutions fall at the extremes of the spectrum. Institutions with high research and publishing activity also consume, or read, scholarly publications at the highest rate; and even at primarily “teaching” institutions, some members of the faculty are occasionally or actively publishing.

The main revenue to any publisher from a “Read” consortium (or institution) will always derive from subscriptions – any Article Processing Charges (APCs) will only provide minimal revenue in this scenario. Germany’s Projekt Deal and the California Digital Library (CDL) are “Publish” consortia – their institutional researchers publish at a rate far greater than some other nations or consortia. Such institutions have a different investment in what kind of transformative deal they seek, and are offered, than a mostly “Read” consortium. Many library consortia are a blend – there may be a few “Publish” institutions balanced by a long tail of mostly “Read” institutions – and that composition within the consortium may be very different per publisher.

In addition, staff and workflows for identifying and paying for APCs will influence the sustainability of any transformative model involving publishing at the consortial level. Adding or customizing an OA workflow based on APCs for a mostly “Read” consortium may not be cost effective for any particular publisher. OA workflows for a “Publish” consortium might require a substantial investment in staff at the consortial level and the development of workflow tools and infrastructure across multiple institutions, or a coordinated effort by volunteers from member institutions.

What Open Access Means for Library Consortia

Different models are being tested and proposed in Europe, in the United States and in other parts of the world. Consortial deals, in particular, vary widely depending on the institutional composition of the consortium, the heterogeneity or homogeneity of research activity, direct access to grants or other funds to pay for making an article OA, and the aggregate publishing activity with any particular publisher. These factors can be relevant at the individual institutional level as well, but get multiplied when consortia are involved. Just as there are different implications of various OA models for society publishers, disciplinary authors, and global regions, the same holds true for library consortia.

As library consortia in different contexts evaluate their own content deals and subscriptions in the face of OA opportunity, knowing where your organization fits in will be a crucial factor in negotiations.

A Sui Generis Scenario

Library consortia that fall somewhere in between “Read” and “Publish” may be faced with differential investment and commitment from “Publish” institutions versus “Read” institutions as well as having to create different models and workflows for different publishers.

From the point of view of a library consortium, when assessing the agreements finalized by other consortia, and working through what works for yours, it is important to anticipate sameness as a rarity. It’s highly unlikely that OA deals struck with one kind of consortium will be available or workable for another type. (There is some evidence that this is true on the institutional level, too.) Efforts to develop OA models that work for library consortia will take time, as many of our sister consortia have already recognized. While patience, research, and the sharing of information will all be crucial at a consortial level, the ability to identify your position on the Read or Publish Continuum will hold significant weight during negotiations with publishers.

The Example of OhioLINK

OhioLINK has 188 member libraries from 89 higher education institutions plus the State Library of Ohio: 16 public universities, 51 independent university and college libraries, 23 two-year college libraries, 16 regional campus libraries, 8 law school libraries, and 5 medical school libraries. Membership includes three R1 institutions, five ARL libraries, and the Cleveland Clinic. Given the makeup of the institutional membership, sometimes OhioLINK can serve as a microcosm of the U.S. higher educational library market as a whole. (For an OhioLINK-specific analysis of institutional type and library alignment within the context of the University Futures, Library Futures OCLC Research/Ithaka S+R research report, see Constance Malpas’ presentation “University Futures, Library Futures: institutional and library directions in OhioLINK.”)

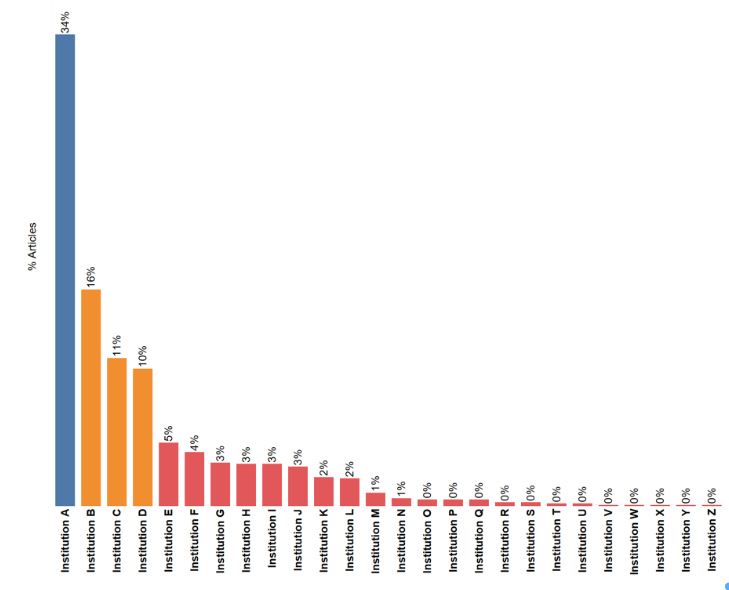

These are OhioLINK publishing and usage figures for one major STEM publisher in 2018. OhioLINK institutions published approximately 1,000 articles in the 900+ titles for which OhioLINK had a subscription. “Publish” activity from OhioLINK researchers accounted for about 0.4% of the total articles for which members had subscription access. “Read” activity was 1,900,000+ full text downloads. One institution accounted for 34% of all published articles in these titles; another group of three institutions accounted for a further 36% for a total of 70% output from the top four publishing institutions; 22 institutions made up the rest of the publishing activity out of a consortium of 90 institutions. The top four publishing institutions published between 10% and 12% of their articles in any kind of OA form (not by consortial agreement or subsidy, but acting individually either at the institutional or author level.) In total, OhioLINK-affiliated authors paid APCs for approximately 100 OA articles: 80% fully OA journals, 20% OA in hybrid journals.

With respect to this publisher, OhioLINK is clearly mostly a “Read” consortium in terms of scholarly production despite a few institutions with heavier publishing activity. With respect to the major STEM publishers, there is no reason to expect that this pattern would not repeat with the same OhioLINK institutions in more or less the same groups. For smaller, more specialty publishers, the institutions might move positions if there was a strong program or professional school like engineering at a particular campus, but we would expect more or less the same distribution given the nature of the OhioLINK membership.

Conclusion

We would expect any Read and Publish deals from publishers to conform to our particular publishing profile, rather than to a California Digital Library profile or a Projekt Deal profile. For some consortia, such as those composed of mostly private colleges, there is even less publishing activity. There is no standard deal that will fit all consortia; some consortia may not be offered certain OA deals at all, or the OA deals on offer will not be financially viable without significant outside sources of funding. Our collective question is: Given that much of the revenue coming from our members is, and always will be, from “Read” = subscription funding, what are the implications for the future financial burden of “Publish” consortia as more institutions become free riders? How will “Read” institutions/consortia participate in OA funding initiatives?

Discussion

23 Thoughts on "Guest Post: Evaluating Open Access in a Consortial Context"

Thanks for a reminder that there is no Procrustean solution for all consortia. This is an excellent question and one that is cognizant of the *economic* realities that accompany attempts to transform publishing: “what are the implications for the future financial burden of “Publish” consortia as more institutions become free riders?”

Some further questions:

1. What would be a reasonable calculation of what *percentage* of institutions really have the deep pockets to experiment with APC models? I strongly suspect that the answer to that is: some very small number, just those that are part of mega-consortia with deep pockets that enable them to experiment with the APC model. Thus the free rider problem, as this author suggests, is going to become more and more thematic. Just wait.

2. From what I can see, the APC model is not viable to begin with. Too much rides on too many variables and their unknown contributions to resolving the pricing problem.

3. Why not a coordinated initiative by all libraries to contract the space of journal publishing, instead of all this focus on APCs, an overly complicated scheme that turns on speculative assumptions? Again, contract the journal space, from which: less demand, lower prices. This will of course involve incrementally increasing burdens on ILL operations as this space contracts, conjoined with concerted efforts to communicate to faculty the rationale for contracting the journal space and educate them about the need for new metrics to evaluate research quality. This is not an argument for doing away for peer reviewed journals; just reducing their number, incrementally.

Thank you for this great post. At CCC, we have experienced the same thing from an institutional and publisher perspective. Most institutions/consortia are driving bespoke deals. At a high level, once an institution has a deal structure it likes, it is expecting publishers to fit within that structure. However at the more granular deal level, this does not yet hold true. The arrangements still vary from publisher to publisher. While you can argue that these are simply “market transition” factors, we do not see them ending anytime soon.

I’d be very interested in hearing more about the “always will be” statement. It seems that eventually Open Access publishing will hollow out the value of a subscription to the point where subscriptions will be dropped. Or, no?

Some publishers report that the growth in the number of non-OA articles they publish each year is enough to offset the OA portion of their portfolios. In other words – subscribers are still getting more paywalled content each year along with increased OA content in a journal package.

Lisa, do you mean this: “The main revenue to any publisher from a “Read” consortium (or institution) will always derive from subscriptions”? I mean that Read organizations will not be generating any revenue from APCs, now or in the future; if OA publishing hollows out the subscription model there won’t be any revenue to speak of from these organizations at all without a completely different model. Substantial amounts of revenue will disappear from the system without a model of supporting OA that doesn’t rely on APCs.

The problem I see with other proposed voluntary OA subventions is that under the pressure of decreasing budgets in higher education generally, but especially in public institutions, administrations will not continue to pay for something that they will receive for free. It’s a nice idealistic hope, but administrations often cut budgets for services and content that are, or were until the moment of the budget cut, perceived to be highly valuable or necessary. Any model that relies on substantial voluntary support of OA (whether OA provided by current publishers or a hypothetical shift to library/institutional owned and operated OA publishing ventures) is highly suspect from my observation of state funded education in the state of Ohio. The financial mantra is efficiency and cost effectiveness; voluntary financial support for content that is free is neither.

Sorry for the confusion! I meant this: “Given that much of the revenue coming from our members is, and always will be, from “Read” = subscription funding, what are the implications for the future financial burden of “Publish” consortia as more institutions become free riders?”

It seems to me that eventually there will be no revenue coming in, rather than always will be? But, perhaps this means, as long as there is revenue coming in it will be Read.

Ah, I see. Yes, the latter meaning —if there is any revenue, it will only be from Read.

Thank you for an important discussion of Big Deals, APCs, etc., as related to consortial negotiations – the posting illuminates some heretofore less visible corners of the OA business conversations. I daresay that there are *many* consortia whose members represent keen readers of scholarly articles, even though those readers themselves rarely or never publish.

As others have noted, UC’s negotiations with Elsevier have underscored the implications of making quantity of published articles an over-riding factor in negotiations, when previously the relevant factors included how many journals a library (or consortium of libraries) chose to provide for its readers, the number of readers, and available budget. Gwen is absolutely correct that in the P&R environment, deals for institutions whose authors publish a lot must differ from those of the numerous institutions that produce less. In the P&R scenarios, high-output institutions or consortia, such as UC, would pay a larger share of the overall global or national bill. Furthermore, should any high-publishing institution shift to an all-publish deal (close to 100% of revenue from APCs), the distortion would be visibly dramatic. That path doesn’t feel quite like a winning long-term solution (and the value of the library in such a setting is less clear).

But it’s too soon to say; there are many OA possibilities, and we are in a period of testing which will work and for whom. Even a number for-pay subscriptions or purchases will surely survive! (One of my stumbling blocks over some OA arguments is their cynicism — the assertion that readers are the same as those researchers who need or want to have their articles published, and that thus they should be paying for the service. Aren’t there other readers (one hopes there are!), and shouldn’t they pay a little something as well, I wonder.)

An immediate take-away from this posting: Information providers should know that library consortia negotiators are savvy and will present the evidence that matches the facts and meets the needs of their members.

Consortia should press faculty to help define a necessary core of journals, in the face of flat library budgets. What journals actually are mission critical to advancing knowledge? Bradford’s law could be one part of the narrative to present to faculty. There may be many creative ways to implement this law’s basic insight.

What to do, though, with the equivalently problematic surfeit of publishing so many articles and the allure of mile long cv’s? That’s the tough piece of this, not the gradual contraction of the journal space, which is eminently doable. How to incentivize people to publish less peer-reviewed content? This is a huge challenge that will only be overcome by encouraging faculty to define and practice new criteria of evaluation that recognize non-journal publications as part of the mix in a research portfolio, complementary to peer-reviewed articles published in a diminished number of journals.

In terms of defining a pluarlity of metrics that can provide holistic assessments of research quality, the theoretical physicist Sabrine Hossenfelder is on the right track with this tool, tied currently to arXiv: http://backreaction.blogspot.com/2019/05/measuring-science-right-way-your-way.html

An analogy to the concept of defining a core list of journal is provided by all those efforts of yore to define core lists of monographs for a library collection. I assume there have also been many attempts to define a core list of journals, already, for smaller libraries. It would be well worth examining the history of those efforts and what criteria were used. Whatever past criteria were used by certain societies to define a core list of journals for purposes of accrediting science programs might also be well worth scrutinty.

The OA emphasis of academic institutions (the “immediate OA” refrain) has served as a distraction from consortial efforts of the kind above and will continue to do so for a good while. Except, perhaps, insofar as the OA movement has led publishers to allow publication of postprints on preprint servers. (Perhaps a future is not *too* far in the offing in which studies about the overlap between OA postprints and their published counterparts can play a role in academic library negotiations with publishers.)

Anyhow, I am not hopeful that much is going to happen that the market will not itself take care of through its own dynamics. Namely, a market induced shrinking of the journal space over a long period of time, given that this has not occurred (and will not occur in the foreseeable future) through an exercise of academic institutional will, esp. on the part of the major league institutions.

In some distant future when the market has imploded under its own weight, then the Owl of Minerva will take flight for new publishing schemes to see the light of day.

[as usual, my views only]

>>>>Consortia should press faculty to help define a necessary core of journals, in the face of flat library budgets.

Both at the consortial level and at the individual library level, “defining a necessary core of journals” takes place continually accompanied with a great deal of time, thought, data gathering and analytics. Shrinking library budgets and rising journal costs have forced cancellations year after year. Cancellations almost always take place in consultation with faculty or departments except under dire circumstances and that is the mechanism for defining a core set of journals. As a collections strategist from one of our member libraries remarked after a deep round of cancellations post-recession, “we’ve cut the fat, we’ve cut the muscle, and now we are shaving bone.”

Most consortia don’t ever directly interact with faculty about collection development; it would be deemed incredibly inappropriate and inefficient to bypass the member libraries, whose staff are specifically assigned to do that work, sometimes at a very granular level. The member libraries then inform the consortium what the desired core journal packages are at the collective level. The more heterogenous the consortium, the wider the spread will be for curriculum and research needs.

I can’t help but laugh as I imagine the horror and amusement with which my consortial colleagues react to “consortia should press faculty.” We have our hands full with our own member library deans, directors and staff.

Re.: “Cancellations almost always take place in consultation with faculty or departments except under dire circumstances and that is the mechanism for defining a core set of journals.” I’m not certain that this is true across the board. That is a politically fraught endeavor. I suspect that many librarians just look at cost per use data and make cuts, on the assumption that faculty have already voted with their feet about what to retain.

Re. “I can’t help but laugh as I imagine the horror and amusement with which my consortial colleagues react to ‘consortia should press faculty.'” This may be part of the malaise–there seem to be no top level efforts to reform publishing, and a disinterest in doing so. I’m of course well aware that many consortia don’t have the staffs to accomplish this–in their current form. Perhaps their missions should shift. But it’s not clear that very large consortia, e.g. the U Cal system (if one wants to call it a consortia) could not engage in such efforts. After all, apparently they have money to engage in experiments about new publishing models, on the taxpayers dime. Anyhow, it seems that none of the players one would expect to execute reform will do so: consortia whose primary mission seems to be brokering package discounts (negotiating clearinghouses, as it were), state systems of libraries, consortia that focus on brokering package discounts, scholarly societies, or faculty themselves. Thus the situation is pretty bleak.

“I suspect that many librarians just look at cost per use data and make cuts, on the assumption that faculty have already voted with their feet about what to retain.”

Brian, I am not sure what librarians you have worked with or work with now that would give you this impression. You are using a very broad statement and one that I would like to note is inaccurate. I (along with a Chair from a member library) run the resource collection committee for OhioLINK. This means that I meet with collection development librarians, representing 118 libraries from across the state of Ohio, in person and on a monthly bases. I have done so for over five years. I can guarantee you that the librarians with which I work, and highly respect, do indeed communicate regularly with their faculty when we are discussing a set of core journal titles and potential cancellations. It’s at the core of their job. They do not take the cancellation of journals lightly. I hear them discuss this month after month. Yes, they do look at cost per use, but they also look at their institution programs (which programs are growing/shrinking) what they need for accreditation, and of course try to ensure they have the content research faculty need to do their job. This is a task to which they bring full professionalism and I can attest that this is all standard practice.

“You are using a very broad statement and one that I would like to note is inaccurate.” As I mentioned, I was suggesting what I *suspect* to be the case, which is different from knowing it to be the case.

I’d qualify what I wrote: when a journal is mission critical, or if there is a question about the necessity of a journal, faculty might get involved. But I’d be willing to wager that at many places, not *all* decisions are made with faculty input. Perhaps they are at large places or within large consortia.

In any case, something that could or should be studied, if there would be any value in doing so, i.e. for purposes of operationalizing best practices for faculty involvement. I suppose a survey could establish this.

P.S. if faculty are so willing to be intimately involved in decisions about journals, perhaps they’d also be willing to provide input to a consortium about their perceptions of the most important or core journals. As I understand it from the other posting, it is not consortial practice to consult faculty, though. Understandably, there are serious limitations on what staff at consortia can do, given other responsibilities.

I wanted to share a perspective from the trenches of Collection Development. I have been a librarian for almost 20 years and actively involved with collection development for around 15 years. My career spans multiple academic institutions and types of libraries.

I can affirmatively say that I nor any of the librarians I worked with have programmatically canceled journals without at least attempting to solicit feedback from faculty or researchers. There are definitely cases where no response is received and then data and the subject librarians educated opinion make collection decisions. My experience is that during times for journal subscription review/renewal use data is important, but that subject librarians also heavily rely on their opinion of a journal/publisher. I have pushed back numerous times on a very high cost per use and the subject librarian would explain to me why keeping that title was essential. I view this as responsible librarianship. Cost per use does not always equate to the utility of a journal for a number of reasons.

Most importantly, in this evaluation is the relationship of the subject librarians to the department they liaise with. The relationship may run the spectrum from highly engaged in departmental function/research to almost no relationship. However, it is still the subject librarians’ responsibility to understand the curriculum and research output of the department. These two criteria alone can highly influence journal choices. In my experience, most subject librarians have a pretty good pulse of who and what is going on within those departments. I also think this knowledge direct or indirect also helps curate the corpus of journals that an institution subscribes to as ‘core.’

I would also not want consortia to reach out directly to solicit info/opinions from on-campus faculty. In some cases, there are departmental politics or a faculty library liaison that is the proper person for the library to contact. These faculty relationships are sensitive and in some cases personal. No subject librarian or collection librarian wants to receive an email from the department that the liaise with asking ‘what is this email I received from ____________ consortia.’ We get enough of those emails about vendors reaching out to faculty.

Other than canceling one off titles or mid-year budget cuts, librarians should always check with faculty about programmatic subscription reviews or cancellations. It is never a fun conversation to tell a faculty member their favorite journal is being cut, but it is better than canceling it and not having the conversation at all. This is responsible librarianship.

I’ve also had a now very long career in libraries and been through many rounds of cuts. It’s a quite vexing process with huge opportunity costs (in terms of labor and time.) But it has to be done, and done well, even if librarians could do many far more positive things to do to serve their communities than engage in enervating rounds of negotiations.

To your points, I’m not advocating not involving faculty entirely. In an ideal world, that would happen. But a question here is whether librarians who have multiple subject areas of coverage always have the time to keep faculty apprised of *all* aspects of journals collection development. E.g., if components of a Big Deal (not subscribed titles) change because of publisher changes, there’s a question whether time is better spent on other aspects of librarianship rather than developing individual lists of changes that affect each department. It really depends on what goes by the wayside if one spends the time to do all this. Large places with huge staffs are different from mid-sized to small-sized institutions, for which HR considerations become paramount. You seem to be suggesting a one size fits all prescription about what librarians everywhere should do. Maybe that’s true ideally, but there are hard realities to contend with.

The key for any instituion is to maintain a list of faculty requests to make sure that we’re doing the best we can to meet demand for titles as yet inaccessible and to review those lists periodically (bad pun) to ensure that happens, and to inform faculty that we have this list of requests. The key is also to respond to departments that have an interest in granular engagement with the selection process. Up until recently, I just haven’t had those types of requests for a very long time. Not sure why, but one can speculate. When those requests come in, they have to be dealt with by educating faculty about what is feasible and what isn’t.

As for journal swap outs that are allowed for the subscribed content component of Big Deals, cost per use has its limits, as do all metrics. If you have a better metric, do let me know. It’s not clear however that it is not adequate for the purpose at hand. Presumably it is the overriding metric used by all libraries? (Other examples of metrics might be faculty pubs in a given journal or citations to particular journals, but for the latter I imagine this correlates even if not perfectly with raw use.)

Institutions with flat budgets have to be very cost conscious, so some metric is needed. Cost per use is a relatively easy to generate metric. Others can be time-consuming. If a journal is just not seeing use, in my view it is poor stewardship of resources to maintain it, including for merely political reasons having to do with special relationships a librarian might have built with specific professors. (I’m taking a STEM perspective. Cost per use may be terrible as a metric for humanities; I just don’t know.) If a faculty member wants a renewal of an underutilized journal that they think should be restored, that is worth taking into account, but with a hard-headed look at whether there is good reason to think the journal will now see more use than it did.

All that being said, I’m wondering if there are any studies of faculty input into collection development, and the degree thereof across a spread of institutions, and whether there are mechanisms for informing faculty of journals that are easy to implement. One problem is how to assign subject bins for journals, given that so many journals are now interdisciplinary, and how to match those subject lists with prices for their components. Creating these lists is really time-consuming, esp. for mid-sized or small places that just don’t have the staff to do this consistently and well.

I’ve had anecdotal responses to my comments to this TSK article, including from one consortium (Ohio). Maybe Ohio has unique practices, maybe it doesn’t, when it comes to consortial practices and the perceptions of faculty involvement in decision making about journals. Maybe some consortial settings make it easier for faculty to be involved. I just don’t know and would like (again) to see relevant studies of these questions, and digest them in an open-minded way. I suspect that practices are more variegated that commentators have suggested. Even just on the basis that institutions typically have different practices for a variety of reasons.

Shfiting subjects, I think commenters on my initial comments have been reading far too much into my comment about the role of consortia with respect to faculty input. You are right to say “no subject librarian or collection librarian wants to receive an email from the department that the liaise with asking ‘what is this email I received from ____________ consortia.’”Certainly I was not advocating consortial end-runs around librarians, for purposes of soliciting input. (Vendors who do that, which sometimes happen, have heard from us about this practice in certain cases.)

I had in mind something much different and should have elaborated the point initially. The idea is that there could be consortial involvement in soliciting faculty input in some systematic way, on a voluntary basis, of groups of faculty in a given field who would be asked to define what journals are sine qua non for their subject. Ideally this would be part of a large undertaking by a number of large consortia, all part of an attempt to define what set of journals is really necessary for advancing knowledge, with Bradford’s Law or something in the background.

The larger context of the point is that there is going to be an inevitable contraction of the journal space, given that publishers continue to inflate prices and many library budgets are flat. Something has to break. (A logicallly independent point: this is arguably a *good* thing–too many new journals are being spun off, and far too many salami-sliced peer reviewed articles are being published, and the intergenerational transmission of scientific knowledge is going to suffer because of it, not to mention the huge burden imposed on peer reviewers.)

Why not ease the transition to this new contracted environment in a systematic way? As mentioned, many consortia are very understandably not positioned to do this because they are understaffed. Otoh, if (e.g.) a U Cal system is willing to devote public monies to speculative spending to support the APC model (on quite questionable grounds, imo, and as elaborated in other combox postings), why couldn’t it do something along these lines to help all the rest of us–namely start defining what core of journals are really mission critical? So that when the inevitable contraction occurs, we’ll all know what is mission critical. The counter-argument is that one size does not fit all. However, definitions of core journals, defined on sophisticated grounds (*not* based on impact factors), could be a guidepost (one among others) as library budgets cannot keep up with the glut of publishing. Societies should be doing this, in theory, but they use journal revenues to fund society operations and so won’t have any interst in this project.

Anyhow, it’s pretty clear that attempts by libraries and librarians to transform scholarly communication, to combat the pricing crisis, do not appear to be going anywhere. (It’s a long story, but the OA mantra has distracted from other approaches that could concurrently reduce prices and also assure OA.) Far more likely is a scenario in which the market of its own accord achieves contraction of the journal space. Perhaps the market will create a “spontaneous order”, along Hayekian lines, that will sort all this stuff out. Esp. given that coordinative efforts by libaries and librarians are not achieving anything to address the pricing crisis. Certainly many librarians are great negotiators, but still, this just perpetuates the problem.

Some of the views here are in a preprint I wrote, which I’m now over-hauling significantly, esp. in light of what I’ve learned since writing it. Particularly now having adopted the view: little will cure the problems in the scholarly publishing system any time soon. And better to sit back bemusedly as it collapses, as a condition for new solutions to arise of their own accord. Hopefully ones which retain what is best in the last several centuries in scholarly communication.

Brian, I’m a little confused by your suggestion to get faculty to create core journal lists. Haven’t these existed for a long time?

Earlier, I mentioned the following:

“An analogy to the concept of defining a core list of journal is provided by all those efforts of yore to define core lists of monographs for a library collection. I assume there have also been many attempts to define a core list of journals, already, for smaller libraries. It would be well worth examining the history of those efforts and what criteria were used. Whatever past criteria were used by certain societies to define a core list of journals for purposes of accrediting science programs might also be well worth scrutinty.”

It would be interesting to see if other librarians are using core journal lists. I haven’t. They may prove increasingly relevant given the inevitable contraction I was harping about. It would be interesting to look at the criteria by which they were developed. Did impact factors play a role or equally problematic metrics? This would be an interesting project for someone, to look at their history. Perhaps more to the point is: what more sophisticated metrics should guide journal selection as the journal space very gradually contracts in the face of diminishing library allocations?

A big question, one too hard to tackle on a nice Friday afternoon! Best regards all, I know all this sounds cantankerous. Please attribute it to annoyance at the problematic aspects of scholarly publishing, which have had so many opportunity costs (HR, and money) for libraries and librarians.

Joe (if I may),

I’d need a much more elaborate story than a simple claim that it “continues to grow worldwide”. In what fields? Year over year revenues? In the academic market? If the academic market, in terms of university expenditures?

The key question is: do you *really* think that academic places with flat budgets can continue forking over money toward journal prices in excess of the CPI? Will provosts materialize to fund all this?

And there is a distinct question: what harm to scholarly communication is being done with so much stuff being published? A key ideal of librarianship is preservation of the scholarly record for future generations, and for the new crop of researchers. Can the ongoing glut of research really help here?

All ears, as long as one’s interlocutor attends “to the facts”, as you put it.

I’ll let Yale physics professor Jack Sandweiss do the work of commenting on the glut of publishing, and its repercussions for science:

https://journals.aps.org/edannounce/PhysRevLett.102.190001

The glut problem is even more problematic than the pricing problem, from a long run perspective.

I might add, however, that as in all things in life, it’s a matter of where one sits. A publishing consultant views the world much differently from folks who have spent years doing as much as possible with limited budgeting.

Brian, you have now insulted librarians and consultants. Who’s next? Faculty? Why not pick on students?

The evidence for growth in scholarly publishing is found in the companies’ financial statements. It is an entirely different question to ask how long that growth will continue.

The “glut,” as you call it, is a function of the amount of research being conducted, which is growing, and the connection between published research and T&P. This is a systemic issue. I don’t see how Wiley or Sage or OUP can solve it.

Insults? Not intended, and of course profuse apologies if it came across this way. It is of course human to respond strongly when one’s views are not taken seriously, or so much is read into them that were not there to begin with.

Just a realistic assessment from someone whose watched all this for two decades. No more or less a realistic assessment than what you are counseling. Is it insulting to ask hard questions?

I stand by my critiques of aspects of the OA movement and regard it as intrinsic good, as mentioned, but have concerns about its current course. I also qualified my comments about consortia, mentioning that they are understaffed, but also remarking that the really big one have special responsibilities. This should have been clear from a detailed reading of my comments. I also stand by my critiques of how the OA movement has distracted from aspects of the economics of publishing. Perhaps you would even agree. There are people in my profession, not all, would stand by aspects of these critiques, for which I claim no originality. Minority views, but worth stating, and more people in my profession should be asking these questions.

I entirely agree with your statements in paragraphs two and three. I don’t recall saying that I thought commercial publishers would or could solve them. Nor are any of my comments intended as anti-business. In fact, many business opportunities will emerge if the system changes.

I do think producer side, something could be done by researchers and their societies. Librarians have been very instrumental in promoting OA, and I don’t entirely think they are incapable of effecting reforms in the system. People in the trenches like me are too busy though to be able to do much, other than educate people about bibliometrics, where best to publish, and provide a critique of the publishing system and the best aspects of its very long history.

The fact that I disagree with some of their views is merely an attempt to get my highly professional and excellent members of my profession to think about their assumptions. Is that a bad thing?

As for insults, you might want to look in the mirror and examine your own rhetoric and tone in some of your own comments directed to my comments, and instead respond by providing helpful analysis. Frankly I’ve found them rather personalized. I’m willing to dialog, but don’t appreciate the way you single out bits and pieces of what I’ve said and their tone, plus the fact that they seem directed to just one voice.

TSK is supposed to be a forum for constructive dialog. Again, it has not been my intent to do anything more than ask hard questions, not ruffle feathers. If some people react to them merely because they attempt to be probing, this is not my problem. Some of the comments perhaps elicited strongly worded replieson my part, only because those comments were strongly worded. Did you read those other comments and why aren’t you reacting to them as well?

In any event, you will be happy to know that the comments grow out of a project (for which many wonderful colleagues in the profession and outside it have provided numerous helpful suggestions!) that is winding up, given the diminishing returns of participating in these discussions. I’m on to more constructive projects in my remaining years in a long and proud profession that has helped conserve and transmit knowledge through the centuries.