Given the onslaught of stories about AI, it should not be surprising that reporting of “trends” will sometimes miss the mark. For example, last year there was a reported trend arguing that training materials used for AI were “disappearing.” This was advanced by a preprint entitled “Consent in Crisis: The Rapid Decline of the AI Data Commons,” and was then picked up by outlets such as The New York Times.

We begin with a TL/DR on the NY Times article:

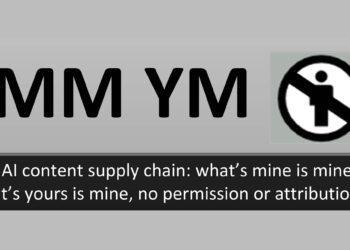

- AI was trained by copying massive amounts of content from online sources without the consent of the content owners. Content owners are now taking various steps to prevent/object to those activities in the absence of a license. This is harmful to, especially, non-profit researchers and smaller AI startups as the data disappears.

Wow. First, let’s get this out of the way. Data is not disappearing and did not do so in 2024. It is still there, with more being created every day. In 2025, forecasters predict humans will create 175 zetabytes of new data. That’s 175 followed by 21 zeros. What has changed is that creators are now directly expressing the need for consent prior to use. These are very different concepts.

Data – or, as we like to call it, books, journals, songs, and other creations of human ingenuity, creativity, and culture — is continuously being created. While the research paper calls the demand for permission a “crisis of consent,” we would argue that under normal human social contracts, requiring an owner’s consent before taking their property is the opposite of a crisis. But why argue semantics?

Let’s discuss why this is occurring now and what it means.

Why is this happening today

Until recently, most publishers were not aware of the possibility that their online materials would be used to train AI. Not knowing about AI, they did not say anything specific about AI in their general rights reservation language.

As a legal matter, this lack of information should not be interpreted as permission to copy materials. AI training involves the making of copies. Under the Berne Convention and basically every national law, copying requires explicit consent from the rights owner unless a copyright exception applies. There was no need for a rightsholder to say anything on its content. Any use not expressly permitted was, by definition, excluded. And it would have been especially odd to expressly reserve AI rights before AI existed.

Even in circumstances where an exception applies, “opting out” or “expressly reserving” rights does not usually change anything. Exceptions typically apply regardless of whether the rightsholder consents. That’s pretty much the point of exceptions: they expressly eliminate the need to acquire consent for a certain class of users or a certain type of use.

That being said, the EU recently created a major exception to the rules on rights reservation. Under EU law, commercial reuse of content for text and data mining is allowed unless the rightsholder expressly reserves its rights, in which case a license is required. This creates a strong incentive for rightsholders to place explicit language barring the activity and is one major reason that we see this language now. Uniquely, under EU copyright law, silence implies consent to that specific exception. In addition, under US law, explicitly reserving rights in this manner will never harm a plaintiff in a copyright infringement suit. It might help and it might not (it will not help if it is fair use), but it will never hurt, especially before a jury or in a damages inquiry.

Does restrictive language mean materials can never be used in AI applications?

Of course not. As stated above, content is not “disappearing.” As noted in one of the many contradictory points made by the NY Times, licenses are available and are being entered into by AI companies and rightsholders. The article seems to confuse the market. Yes, when large companies such as OpenAI enter deals with a large publishers, that may be newsworthy. When a smaller startup enters a license with a rightsholder, it might not make the news, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t happen. Smaller AI firms do enter into licenses. At CCC, we work with quite a few of them.

And yes, to paraphrase a commentator in the article, it may be harder for smaller companies to afford licenses than large ones, but that is also true about their computer chips and electric bills. Unlike some other costs, licenses generally are less expensive for small and medium enterprises (SMEs). This is certainly true of the collective licenses of the type CCC offers. Moreover, given that most publishers are themselves SMEs, licenses (especially collective ones) give them access to markets that would be difficult to address on their own.

In public policy debates, big tech unironically argues, “what about the SMEs?” to justify their own appropriation of content. Simply because a creator devoted their career to creative pursuits by writing books or photographing war zones does not mean they need to financially underwrite Silicon Valley entrepreneurs until the entrepreneurs are big enough to pay bills, or more accurately, given the number of litigations brought to date against AI developers, litigate in lieu of paying them.

Licensing solutions exist that enable companies, large and small, to obtain content and usage rights under flexible terms that account for the relative size of the players in the market. Differentiated market pricing in licensing has existed for centuries and is the norm, not the exception. Academic pricing is different from commercial pricing; for profit pricing is different from non-profit. Applying these concepts to licensing for AI training is neither complex, new nor innovative.

Reservation of rights does not limit content “available” for research

Again, material remains available, so the question is really one of economics.

The line between so called “non-commercial” or “research” use for AIs is blurred, to be generous. Want to know who is a tax-exempt non-profit organization, presumably engaged in non-profit AI research? OpenAI. Well, sort of. Its corporate structure is complicated, but as best we can tell, the non-profit co-owns an $80-billion for-profit arm. Microsoft (no one’s example of an eleemosynary enterprise) is a co-owner of the for-profit arm.

Moreover, non-commercial is not a free pass for infringement, as the Internet Archive learned the hard way.

Publishers have historically been open and willing to support non-commercial research use of their materials at no additional cost. Some of us will remember that as far back as 2017, leading STM publishers signed onto a policy committing to offer “researchers and institutions to which researchers are affiliated comparable and equivalent access rights for the purpose of non-commercial text and data mining of subscribed journal content for non-commercial scientific research, at no additional cost to researchers/subscribing institutions.” Material is plenty available.

There are, however, meaningful limits on available training materials

In a more recent article, the NY Times noted another, more real phenomenon; the internet is actually finite. Whether lawfully or not, many of the largest AI systems have been trained on what is available online. While new content of course is added every second, the amount and quality of the new materials online is of limited use in trying to get AI to the next level.

Offline content can fill this gap and provide AI companies with access to content which provides competitive advantage. Many publishers are open to licensing on equitable terms. Unlike the so-called “disappearing data,” limitations on/of online content are real and provide meaningful opportunity for big tech and creators to work together.

Conclusion

Publishers of quality, valuable materials now have every incentive to restrict access to their materials and a justified suspicion of the AI industry. Publishers control massive pools of high-quality validated content not available on the open web. This can be used to train AI. The barrier to AI advancement is not the lack of content or rights reservation, but the unwillingness of (some in) tech to pay a fair share to use it.

As noted by the NY Times in the first article:

[T]here’s also a lesson here for big A.I. companies, who have treated the internet as an all-you-can-eat data buffet for years, without giving the owners of that data much of value in return. Eventually, if you take advantage of the web, the web will start shutting its doors.

Discussion

7 Thoughts on "AI and Content — The 2024 Trend that Wasn’t and the Related Opportunity that Exists"

Interesting article, thanks. Is there any evidence that fears about the use of academic publications in LLMs is causing authors to choose more restrictive open access licences?

Richard, this is more anecdotal than “evidence,” but I have certainly heard that because of LLM training, many stakeholders are questioning whether to continue use of broadly open licenses (mainly CC By). No one anticipated this use when the licenses were originally adopted, and I expect that policies will change quietly.

“AI training involves the making of copies.”

Indexing websites involves the making of copies. ( Stop me if you can already sense where this is going. )

“Under the Berne Convention and basically every national law, copying requires explicit consent from the rights owner unless a copyright exception applies.”

No website owner has given the explicit consent for their website to be indexed, cached, regurgitated in part or in whole by search engines and archiving services.

“As a legal matter, this lack of information should not be interpreted as permission to copy materials.”

Yet the lack of a “robots.txt” file is interpreted exactly in that manner. Moreover, the default behavior of services respecting a “robots.txt” file is that everything is allowed unless the “robots.txt” file says otherwise – and is a behavior that is welcomed; you *want* your website to be indexed and discoverable on Google, Bing, Yandex, and any other current or future such services.

The “robots.txt” for sspnet.org for example instructs only disallow rules. Everybody is welcome to index – except those excluded. It should come as no surprise that the listed services for exclusions are major AI bots, such as ChatGPT and Claude (but no Perplexity; how perplexing.)

But when the indexing is not primarily for the benefit of the site, of the author, etc. – and let’s be clear with an example: recipe websites don’t exist for the benefit of the would-be chef by providing a recipe, they exist for the ad revenue provided to the author, thus leading to the SEO phenomenon of entire life stories being attached to those recipes in order to increase search engine ranking – but to the benefit of others, that logic of opting out gets thrown out the window, and opting in is suddenly a must that is backed by legal, socioeconomic, and ethics structures that for inexplicable reason are absent in the other scenario.

I’m not suggesting that every author should be charitable (sometimes one’s vocabulary causes one to miss the charitable for the eleemosynary, to contort a saying) and let AI companies have a free-for-all with any and all content. But perhaps a restructuring of this article based on the core concept of “we expect to be ‘fairly’ compensated monetarily for anything and everything” is warranted. A web where information was freely shared for and among all, to the benefit of all, is coming to an end in favor of a traditional haves vs have-nots structure, and though perhaps rightfully pointed to as catalysts, it isn’t solely the AI companies who are to blame, but also the authors of recipes who expect a portion of your gross revenue every time you sell a cookie based on that recipe even after you already paid them for the recipe, and made extensive adjustments of your own to it.

Steven- I know this is not your larger point, but I do think analogizing indexing to AI training is not really apt. When a creator posts content online it is with the desire to be indexed and the creator receives benefit from the indexing and links. In the case of AI training, most creators had no knowledge this would happen and derive no benefit from it. If anything, it reduces the potential license value of the content, does not provide credit or traffic, and may compete in the output.

And what about the argument that we’re already paying for most of the data? Doesn’t the majority of published research come from sponsored government grants, paid for with American tax dollars? Publishers do a tremendous service policing the quality that runs through their journals and promoting impactful scientific discovery, but shouldn’t they be making their profits for those services on the front end and not the back end? Maybe the data restrictions should only exist for privately sponsored research where the data is in fact not already paid for by the public.

In my opinion, the data should be owned by the people that funded the research. We shouldn’t restrict what can be created from the content and limit the potential of AI-powered discovery because publishers now believe they uncovered undiscovered gold in their corpus that they can profit from.

You claim that ‘The barrier to AI advancement is not the lack of content or rights reservation, but the unwillingness of (some in) tech to pay a fair share to use it.’ I’d argue that giving the power to police AI development to the publishers can introduce a detrimental bottleneck to the advancement of AI-powered solutions.

One might argue that the data from a research project is a separate output from the research paper, essentially a report written about the project. Most research papers do not contain the full data set from the research project described, and there are an increasing number of funder policies requiring public availability of any data derived using their funding. This data is usually released under a CC0 license, meaning it is considered in the public domain and available for whatever reuse is desired.

Agreed David. Data, including governmental data, is not protected by copyright. It is free to reuse and should remain so. I could have been more clear in my article that the so-called “data” that is allegedly “disappearing,” is newspapers, media, art, music, etc. As far as I know, the cases pending have nothing to do with government funded research.