As we enter 2026, we mark the end the first quarter of the 21st Century. For those of a certain age, the recollection of the start to the millennium and the enthusiasm and excitement that the start of the new year presaged. There were many visions of what a transformed publishing world would look like resulting from a digital revolution. It is worth revisiting those ideas, what eventually transpired, and what might await in the next quarter century.

With the advent of a more interactive, social web in the mid-2000s, visions of a more interactive publication process circulated. Early, free access to preprints would free scholars from the cumbersome and slow publication process. Building upon this content, new visions of overlay journals would begin to proliferate allowing for alternatives to existing journals. Expectations that the new digital paradigm would introduce greater transparency and open peer review would dominate. The scholarly publishing world certainly has changed a lot in the past twenty-five years, but not always in the ways we might have expected.

So here are a few of my hot takes on the past twenty-five years.

Digital creation

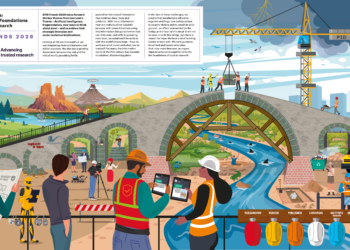

There can be little doubt that digital processes have significantly sped up the process of content distribution. Prior to the 1990s, publication time from manuscript submission to publication was measured in months, if not years. As one example, Aileen Fyfe, examined data from the Royal Society, beginning about the year 2000, publication time, average publication time dropped 75% from 40 weeks to roughly 10 weeks. This was confirmed in the subsequent years, but the pace of the time-savings has slowed. Christos Petrou, founder and Chief Analyst at Scholarly Intelligence, explored this further in a 2022 Scholarly Kitchen post. He found that from 2011 “It took 199 days on average for papers to get published … and 163 days in 2019/20. The gains are primarily at the production stage (about 23 days faster) and secondarily at peer review (about 14 days faster).” The reasons for this can be tracked to authors submitting electronic files at scale as desktop word processing became ubiquitous in the 1990s. These files could be fed into digital production processes that included manuscript tracking software introduced in the mid-1990s. These tools expanded in functionality and became widely deployed in the first decade of the 2000s. Consistent file formatting, through the adoption of standard production file formats, such as JATS, both reduced production time and significantly reduced production costs. Realistically, the transition to electronic production has probably squeezed as much time and cost-savings from the process as is possible. Certainly, advances in technologies and systems will remain to be achieved, but these improvements in time and cost savings will be at the margins, if quality is to be maintained.

The initial visions of online publication included far more robust formats and structures than this historical paper version of content could support. Since Ted Nelson coined the terms “hypertext” and “hypermedia” in the same 1965 paper, the vision always included a variety of media types that could be connected, such as text and film, etc. Scholars were quick to seek to include a variety of supplemental materials with their manuscripts. It didn’t take long for these materials to become unwieldy in the publication process and initially publishers didn’t know how to effectively manage these supplemental materials. Simultaneously, researchers sought to share the datasets that underlay their research findings. Investments in research data infrastructure, in the late 2000s, as well as work on research dataset identification, and data citation practices, helped to advance the formal publication of data sets and their recognition as first-class research outputs. Other advances in creating, labeling, making data sets discoverable, reusable, and tracking their usage have been advanced by the Research Data Alliance since its foundation in 2013.

Despite all the work, it has taken a long time to build usage of data sets. Early research conducted by Nicolas Robinson-García, et al., on published data set usage found 88.1% of records in the Data Citation Index received no citations, though this varied by repository. Later work by, Nushrat Khan, et al., showed an increasing pace of research data reuse and citation in the domain of biodiversity using the GBIF, from 2013 to 2018 from near zero to nearly 40%.

There are a variety of other research outputs that have been made possible via digital content distribution over the past quarter century as well, but that are slower in gaining adoption. Video also began widely appearing as supplemental online materials in articles in the 2010s. It has gained significant application, particularly in medical fields. Software code sharing is gaining traction, albeit at a much slower pace than data or video. Publishing trial protocols has become increasingly frequent, with a five-fold increase from 2007 to 2017 according to one study. As some domains of research have begun utilizing Virtual Research Environments, also called science gateways, research platforms, or virtual labs, new work on how the protocols, software, outputs and data can be packaged and shared has begun. New tools to create content in different forms, from images to videos or transform text to speech or video will expand the formats that content will take in our ecosystem. Ideally, these tools will also assist in making the existing content more interoperable and reusable, the two elements of FAIR that have been hardest to achieve.

Technology Adoption

Technology adoption is slower than most people think. It takes years, even a decade or more, for technologies to be broadly applied and used in the ecosystem. Even seemingly simple systems upgrades can take years to be implemented, because of business priorities, social expectations, or purchasing cycles. We are often encouraged to buy into the hype of the next technological revolution, only to be caught waiting around for the implementation of last year’s technical advances. Regardless of the promise of any new technology, it is unlikely that fundamentals of business prioritization processes, investment resources, user preference inertia, or the human expertise to deploy tools will increase as fast as technology is advancing. This will cause most organizations to be faced with ever increasing levels of technical debt over time.

Scholarly authorship motivations are incredibly difficult to shift. We have seen many attempts over the past twenty five years to change author or researcher behavior. These have included trying to motivate authors to publish open access, to author rights retention addendums, to shifting assessment away from the Journal Impact Factor. Certainly, there are trends that have changed behavior in the community, notably with OA publishing over time. However, as a general rule, the research enterprise is extremely conservative when it comes to adapting to change that impacts their methods of assessment, promotion, and tenure. While much consternation is pointed to scholarly publishers or data aggregators as the source of these problems, they are rooted in the practice of the academy. It is highly likely that many of these are issues that will only be solved actuarially.

The process of worldwide content creation is accelerating faster than any human’s ability to ingest and understand that content. One approach to solving this problem, which has been tried for centuries is specialization. No one can be an expert in everything, but one can be an expert in ever increasingly niche domains. This process will inevitably continue — as it has for decades — as domains fracture into ever smaller subdomains. What will be new looking forward is the application of technological tools and specifically AI agents to do the reading for us in a vain attempt to stay abreast of the deluge of content. While some may appreciate simply reading the abstract, an abridged version of a book, or simply a review of the content, these are simply not a replacement for doing the reading (or listening or viewing) the content by oneself.

Open Access and Open Sharing

The Open Access movement has been a tremendous success and has significantly transformed the scholarly publishing landscape. Despite the recent complaints that OA was “a movement that had promised a great deal but has failed to deliver on its promise and seems unlikely to do so,” it is hard to see this movement as being anything but one of the most radical transformations in scholarly publishing. If one takes the original Budapest Open Access Declaration at face value, the goal was to create an environment where content was freely shared with the public on the internet, without financial, legal, or technical barriers, and that it was free from restrictions on reuse, apart from recognition of authorship. In 2002, the BOAI envisioned an ecosystem that included both preprint repositories and OA journals and other new approaches. A 2025 NSF report described the impact: “Since 2003, the number and share of OA articles has grown from an infrequent type of peer-reviewed publication to almost half of global publications in 2022.” OA certainly has issues related to equity and inclusiveness, long-term sustainability concerns, regularly evolving business models, as well as a flattening adoption curve and changing funder priorities. However, the transformation from subscription to OA models must be viewed as a transformative success based on its originally stated goals.

Along with the digital movement to open access, a radically open approach to copyright was also released at the start of the 21st Century. Creative Commons was launched in 2001 as a strategy to use copyright to provide “the legal layer of the open infrastructure of sharing.” In the subsequent years, while no concrete numbers are available, certainly there are hundreds of millions of CC-licensed content objects.

It is clear however, that people have serious misgivings about the implications of content offered out to the world with radically open licenses. Over the past five years, AI tool developers have sought to ingest and train large language models with all the content they can find. CC-licensed content is ideal and sought out for training. It turns out, however, that many authors are not pleased their content is used in this way. However, this is exactly the purpose of CC licenses. Recognizing this challenge, CC launched a new project last year, CC Signals as an attempt to rebalance the use of content. CC Signals attempts to “allow dataset holders to signal their preferences for how their content can be reused by machines”. Although the system is just released in an alpha version, without any meaningful enforcement mechanism in the US, it is unclear if AI developers will respect these Signals. (It is worth noting that the system is potentially legally binding in the EU under the AI Act’s opt-out mechanism.)

The entire open system that was built on the early BOAI and CC licenses efforts are premised on recognition of the moral right to attribution. Without meaningful attribution, generative AI systems that summarize, quotes content verbatim, or even mashes up ideas to generate new text, break the chain of recognition that is the only compensation that scholarly authors receive. The revolution in content sharing that was unleashed in the early 2000s with the launch of the Creative Commons movement is at risk. Many authors have expressed deep concerns about the lack of control they have in how these systems are reusing their content and have questioned the prevailing paradigm of open sharing enforced by copyright law (as well as filing many lawsuits). Without compensation or even recognition, what is the value for authors to create content if only trillion-dollar companies can benefit or profit?

Discovery

Content creation and distribution are only two components to the scholarly publications process. Another critical activity is discovery, which has also been radically altered in the past two and a half decades. In the same paper where he coined the term “hypertext” in 1965, Ted Nelson wrote “Surely half the time spent in writing is spent physically rearranging words and paper and trying to find things already written; if 95% of this time could be saved, it would only take half as long to write something.” Indexed discovery services for online content have transformed how people find content of all sorts, but particularly research content. With its roots in citation-based discovery tools, Google and Google Scholar ended up replacing for many users the diversity of domain-specific and even research-specific discovery tools.

There are many, many more initiatives and aspects of the scholarly publishing system that have changed over this time frame, and I’ve only touched on a few. There are certainly others, which I’ll expand on in other forums soon, such as persistent identifiers, metadata, preservation, and research assessment and how these things have impacted our community. I’m sure many of you will have your own thoughts about what has worked, and what hasn’t over this time. But for now, let’s focus briefly on the future.

Looking to the future

Despite the warning: “It is always dangerous to prophesy, particularly, as the Danish proverb says, about the future.”, I’ll make a few quick hot takes on the next few decades. Looking forward to the next quarter century, here are some thoughts about key drivers and trends to look out for:

- Researchers will continue to value reputation and impact of their work. This is certainly obvious, but its implications are profound both for publication choices, the growth of OA and the use of CC licenses. Decisions about where to publish are rarely driven by concerns about the scholarly communication ecosystem or openness, but rather the reputation of the journal and the best venues for the research and its impact. While the infrastructure exists to distribute content without journals, authors will continue to prefer the validation and certification that journals have historically provided.

- AI tools will support greater access to research content. This will be achieved through enhanced accessibility conformance, machine translation for non-native speakers, and language simplification to allow non-specialists to understand content.

- The entire research publishing ecosystem will be whipsawed by changes in policy and funder mandates about what is acceptable, what will be funded, and how much it will be funded. This will make long-term planning, investment decisions, and sustainability difficult, particularly for small- to mid-sized publishers.

- The research graph is only partially complete. There are a lot of research outputs and elements of the research ecosystem that need to be identified and described in the research ecosystem to connect all the pieces.

- With the recent explosion of machine reading tools and AI chat tools, many are wondering if these new tools will unseat existing search services. This is unlikely, as all the major services are incorporating these features into their services. While some new players may enter the field, given that most of the current LLM models are comparable in performance and service providers are implementing a small number of large base-language models. It is unlikely that the existing search tool providers will exit the market.

- Simply: Machines — while helpful — will not replace humans in research, vetting, or assessment.

Happy New Year, everyone! May the next quarter century be peaceful and prosperous for all of you.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Hot Takes on the First Quarter of 21st Century Scholarly Publishing"

Thanks Todd – congrats on managing to shoehorn two of my favourite quotes/saws into one post (“these problems will be solved with funerals” and “making predictions is risky, especially about the future”).

I would also wager that research graphs are going to become orders of magnitude more sophisticated in response to LLM’s need for answers to detailed research questions, but – as the great English philosopher/footballer Paul Gascoigne once said: “I never make predictions, and I never will”