Do publisher’s non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) lead to higher prices in the marketplace? If not, is their purpose little more than kabuki theatre?

In this piece, I want to explore why some publishers insist on NDAs, why some librarians sign them, and why others categorically refuse. In the end, the role of NDAs may be less about economics and more about saving face.

But before I get into discussing NDAs, I need to talk a little about pricing; specifically, about the differences between list (or sticker) prices and real (or actual) prices.

Most of us are used to paying list prices for most of our daily transactions. We don’t negotiate on the price of a tube of toothpaste or a loaf of bread at the check-out line. Prices are tallied by a clerk and we simply pay the total with no argument. It’s a very fast and efficient model, which allows most of us to move on to more important transactions in our life. This is not the model for most of the world, where there are few set prices, and haggling is the norm for nearly every transaction, however small. In the haggle, the seller quotes the highest reasonable price and, through negotiation, the price is discounted until it reaches what is considered a “fair price,” meaning a price the reflects the true value to the customer.

In the United States, many states require hotels to post the maximum daily rate for each room–a rate that few of us actually pay for a night’s rest. When demand is exceedingly high–for example, when you need to find a room to attend your child’s college graduation–hotels will charge the maximum daily rate, much to our chagrin, and make an obscenely large amount of profit. We pay these obscene rates because the alternative (not attending a child’s graduation) is just not open for negotiation. In most circumstances, we all receive some discount off the list price.

Similarly, the majority of college students do not pay list price for attending a private college in the United States. According to NPRs Planet Money, the average list price for tuition is more than double what students actually pay, and the gap is getting wider. Students receive tuition discounts for scholastic merit, for financial need, or to achieve class diversity. And, let’s not forget sports scholarships. Discounting from the list price allows colleges to set not just one price–but many prices–for tuition. While the list price of college tuition is increasing much faster than general inflation, the real price of tuition (the actual price paid by students) has been keeping pace, more or less, with general inflation.

Like colleges, most publishers can play with price in some way, and some have been more creative than others. The easiest pricing model is simply to have all customers pay the list price, which has been calculated to recoup average costs plus some profit. The problem with this model, and especially for electronic products, is that it does not account for the fact that some customers will value the product more than others and are willing and able to pay a higher price. At the other end of the market, the list price model locks out smaller customers who are neither willing or able to pay the list price. List price is an easy model, but it minimizes access in the marketplace.

Instead of relying on a single list price, publishers can offer several list prices based on customer attributes. For example, the Ecological Society of America (ESA) offers a tiered model based on the size of the institution (small vs. medium/large), country (U.S. vs. foreign), and format (print plus online vs. online only). Other publishers offer more complicated models, based on the Carnegie classification, FTEs, or number of faculty, post-docs, and graduate students in a particular field. My personal favorite is the model offered by the American Institute of Physics, who developed their own mathematical model, which is based on authorship, usage and subscriptions, to determine institutional classification. The purpose of these classification models is to attempt to differentiate customers into categories and to set a list price that more accurately approximates their value, and by extension, their willingness to pay a differentiated price. Publishers can, and do, put a lot of thought and calculation into setting these tiers but, once stated, there is no negotiation on these set prices. As the ESA proudly proclaims on its pricing page, “Simple licensing agreement — no signature required!”

The last model is the individual pricing model, where each customer is quoted a customized price. This model is reserved for large publishers and aggregators, and there are several reasons why. The biggest reason is that this model is very costly in terms of the time and resources that go into negotiation. If you’ve been involved in negotiating for a big deal, you and many of your colleagues may be tied up for months in the process. Chests are thumped, sabers are rattled, representatives are told to return to their company and to send someone else with authority, who comes back with a slightly better deal. Like college tuition, few institutions pay list price. Most receive some discount from the list price, with some institutions getting better deals than others.

Large commercial publishers do not have as much flexibility with altering prices as we might think. The reason for this is that they are bounded historically through their legacy in the print market. An institution’s price is calculated more by what it paid in the past than its current value of the product. A new publisher, on the other hand, has no historical anchor to what it can charge and is much more flexible in coming up with a new pricing model that reflects an institution’s true value of that product. According to several commercial representatives I spoke to for this piece, they have much more flexibility with the terms of the agreement than with the total price. If an institution (or consortium of institutions) wishes to lower their price dramatically, this usually comes with much more restrictive terms. Unfortunately, we rarely see the terms of these agreements, only total spend, which is not a very helpful indicator of value. Institutions that are paying less are often getting less.

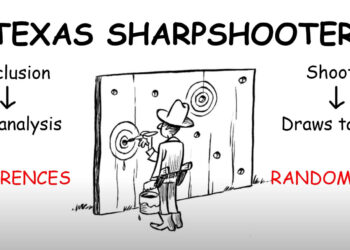

There is a lot of drama that goes on in these negotiations. Some librarians use the media to add to the drama, believing that public support will help their side of the negotiation. Publishers view this tactic mostly a form of irritation. If you’ve witnessed enough of negotiations, they appear like kabuki theatre with each actor assuming his role, and the play concluding when the license has been signed, often with an NDA.

In recent years, there has been a concerted effort to do away with the NDA. The Association of Research Libraries encourages its members to refrain from signing NDA clauses, with institutions, like Cornell University, making this a requirement for all new licenses. There are various rationales made in these policy statements, some economic, others social. If you read them, there is a lot of hand waiving but little detail in how refusing to sign NDAs changes the marketplace for the better. In fact, in speaking with a number of economists, librarians and publishers, I’m left to believe that these policies do little economically: They may in fact lead to increased prices for research libraries. Their real role may be to make librarians feel that they are doing something constructive to change the publishing marketplace–chest thumping, saber rattling–but little else.

NDAs are intended to make the details of each negotiation confidential. In reality, librarians talk and will disclose the details of a deal after an NDA was signed. When I was a collections librarian, I used this technique myself, contacting my colleagues–by phone so as not to document the conversation–almost as soon as I was sent a quote. This leads me to wonder why ARL librarians have called for the end of NDAs, claiming that they interfere with the negotiation process. Or to pose the question slightly differently, if librarians already ignored confidentiality clauses, could the end of NDAs harm their ability to negotiate effectively, resulting in exactly the opposite desired effect?

NDAs allow large publishers to arrive at a customized price for every customer. In a world with perfect price transparency, the best pricing model that publishers could offer is list price (or some variant of it). The result is that some institutions will pay more, and others less, for the same service: An economist would argue that this is an inefficient market.

To me, the real problem with doing away with NDAs is that the transparency exposes the actors to an audience of spectators who can now observe what each side was able to achieve. In this transparency, the drama of the theatre is exposed along with its narratives of triumph and failure. No one likes to feel that they negotiated poorly–librarian or publisher rep alike. NDAs may have no effect on the ability for librarians to negotiate or to change the marketplace for others. The real role of NDAs is to allow both parties to negotiate, sincerely and in private, without the risk of public humiliation from peers.

In essence, NDAs provide each actor a chance to thump his chest, rattle his saber and, in the end, return to his institution claiming victory. Is that such a bad thing?

Discussion

6 Thoughts on "Non-Disclosure Agreements — Economic Tool or Kabuki Theatre?"

NDAs are intended to make the details of each negotiation confidential. In reality, librarians talk and will disclose the details of a deal after an NDA was signed. When I was a collections librarian, I used this technique myself, contacting my colleagues–by phone so as not to document the conversation–almost as soon as I was sent a quote. This leads me to wonder why ARL librarians have called for the end of NDAs, claiming that they interfere with the negotiation process.

I was startled to read this. Although I have always resisted the inclusion of NDA clauses in licenses, when my attempts to exclude them have failed I’ve always honored the final terms of the agreement, and to my knowledge most of my library colleagues do as well. Phil’s observation above leaves me wondering if I’m just naive. I’d be interested in hearing from other commenters (anonymously if necessary) who might be able to shed light on the degree to which the breaching of these terms is a routine practice among us.

Many state institutions are simply forbidden from signing an agreement with an NDA. Even if they signed a license with an NDA, it would likely be unenforceable. Given that, I’m surprised at how often we receive licenses with an NDA clause. Surely, every state university in Illinois has told them it wouldn’t apply. What we buy, and the amount we pay are matters of public record.

I negotiate 60% of my library’s resources and often come across the NDA. I’ve yet to have it removed, but I have used it to the library’s advantage to craft a customized agreement that best reflects our usage of the content. Though I’d love to tell others what I’ve done with pricing and terms, I simply can’t. I know, by receiving an invoice for the wrong school, that my institution pays slightly more for content from one large publisher. However, we chose not to participate in a multiyear agreement, thus resetting our subscribed titles to list price with a higher inflation rate.

At first blush, It seems counterintuitive that any practice that withholds pertinent information from the marketplace could be good for pricing–the invisible hand etc. In fact, according to Phil Davis’s explanation, it is by breaching the terms of the agreement that librarians can achieve better pricing in individual transactions. And by conducting this exchange of pertinent information behind closed doors (“by phone so as not to document the conversation”), librarians not only breach the terms of the deal but also risk running afoul of antitrust law. In years past, I’d have shrugged and said, “Who’s going to sue a librarian?” I think the GSU and Hathitrust suits have answered that one for us.

Of course, this particular marketplace is already distorted by the nonsubstitutability of the goods: i.e., if Elsevier is the publisher of journal X, Springer can’t give you a better price on X. They can offer you a better price on their competing journal Y, but the content must, by dint of copyright, be different. Perhaps this is a case in which OA, by offering a generic version to compete with the name brand, is the best remedy for the pricing problem.

Though not directly relevant to this discussion, it is worth noting that the company that uses NDAs most frequently is Google.

I don’t think I agree with this article’s conclusion. Couple of thoughts: 1) public institutions should be obligated to make the details of most agreements public. Not doing so solely to save face for someone who negotiated a poor deal is unacceptable, in my opinion. 2) at the very least, I try to support publishers who make their list prices public. Without this information it’s hard for me to envision the marketplace functioning even close to efficiently because customers are left with only the publisher’s claims as to how good a deal their quote is. With the hotel room example customers can at least compare their rate to the posted rate, even if they have no idea what their neighbor paid.