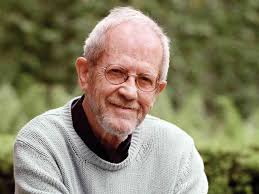

American literature is markedly poorer this week with the death of Elmore Leonard, the undisputed dean of crime fiction. He was the hero of anyone who tried to write good dialogue, and for more than 60 years he was living proof that the vernacular can be divine. He’s famous, among other things, for his characteristically spare and beautifully-crafted 10 Rules for Writers. (He seems always to have followed an eleventh rule as well, one that he didn’t include in his list. That rule was “In every book, the most awful fate should be reserved for the character who is most disrespectful to women.”)

American literature is markedly poorer this week with the death of Elmore Leonard, the undisputed dean of crime fiction. He was the hero of anyone who tried to write good dialogue, and for more than 60 years he was living proof that the vernacular can be divine. He’s famous, among other things, for his characteristically spare and beautifully-crafted 10 Rules for Writers. (He seems always to have followed an eleventh rule as well, one that he didn’t include in his list. That rule was “In every book, the most awful fate should be reserved for the character who is most disrespectful to women.”)

Some years back, on a long and boring airplane flight, I decided (in the spirit of Dan Greenburg’s Three Bears in Search of an Author) to attempt an homage to Leonard — a rewrite of Goldilocks and the Three Bears as he might have done it. I’ve tried to honor all of his rules, including the eleventh, though I slightly broke the first one. Here it is.

BEAR BAIT

(with apologies to Elmore Leonard)

The way it had started was like this: she was sitting at a table in the commons area, with her low-fat yogurt and her bagel, eating half the bagel and wrapping the other half in a paper bag to throw away. He’d ambled over with his tray, a medium Coke and a large order of greasy fries, giving her that look she’d gotten from lots of other guys, but maybe something a little different about his. Cocky, but not predatory.

Him, with a crooked smile that wasn’t a smirk but wasn’t a grin either: “You eat alone too much.”

Her: “How do you know?”

Him, shrugging: “I see you here most days. Girl looks like you, with all those golden curls, eats by herself, it’s because she chooses to. I’m not sure that’s healthy. Can I join you?”

She’d thought, well he’s confident anyway, isn’t he? Not one of the politically-correct fraidy-cats that cringe around campus, asking would it be okay if they held the door for you.

She didn’t say anything and he sat. She liked his tousled hair and the way his t-shirt fit, and she liked the bold way he looked at her, but she didn’t let on. At first.

His name was Stevie. That was the start. A few days went by and some weeks, and they saw each other some more, and then she was waking up three-four mornings a week in his two-room apartment over the head shop, stretching like a cat with the sun across her pointed toes and getting to class late, and liking it.

And then one day he asked a favor. She’d been wondering what his invisible means of support were, but hadn’t ever wanted to ask, didn’t want to screw up a fun thing. Turned out he had a small but profitable piece of the porridge action on campus and in the neighborhood around. He kept it low-key, didn’t antagonize the big players or the cops, just sold mostly to friends and their friends and did okay for himself. Not rich but comfy, tuition covered by his folks upstate.

“My dad’s having hernia surgery, I’ve got to go up to Traverse City, spend the weekend,” he said over a small bowl one morning. “Can you go see the Bear for me? I’ll let him know, there won’t be any trouble. He gives you a case of instant, the twelve-ounce boxes, you give ‘em a quick taste, pay him, drive home, put it in the basement. No muss, no fuss.”

She looked at him. She liked porridge fine, had since she first tried it sophomore year, but this felt maybe like crossing over a line. And maybe she’d heard one or two things about the Bear, about maybe he wasn’t always as tame as you might want him to be.

But in the end she’d said okay, and that’s why she was walking through the woods outside Scio Township right now with $2,000 in her purse, following Stevie’s scribbled directions, looking for a cottage in a clearing.

When she got there and saw it her stomach eased a bit. Cute, homey, some flowers in pots and the walls recently whitewashed, not like the nasty, burned-out apartments favored by the polenta fiends and the pee-smelling gruelheads in downtown Detroit. She walked by those places sometimes and shuddered, hoped Stevie wasn’t headed down that road.

She knocked. The Bear came and opened the door a bit, then wider when he saw her. He was huge, tall and heavy, his head as big across as a serving platter and his belly three feet wide easy. He chuckled as he looked her up and down with his flat black eyes. The eyes stayed mostly below her neck and above her belly.

“Come in, come in. Geez, Stevie didn’t say what a hottie you were.”

He stood aside and let her pass, crowding her a little, and she knew he was looking at her butt as she walked ahead of him into a small living room. She turned and waited.

“The kitchen, the kitchen. The stuff’s on the table. You want a beer, some brandy? I got some nice mead if you like that stuff.”

She walked into the kitchen, put her purse on the table, looked at the box. “No, thanks.”

“All business, huh? Okay.” He trundled in behind her. Mama Bear, almost as big as Papa, was muttering to herself over the stove, didn’t turn around. Goldilocks couldn’t tell what she was saying.

“Mama Bear doesn’t speak any English,” said Papa Bear. Then he laughed. “I know, I know, she’s fat and ugly, but her old man runs the biggest semolina operation back in the old country, so what am I gonna do? She’s the honey jar, you know?” He slapped Mama Bear on the rump and she swatted at him without looking up from her pans.

Goldilocks gave him a look, which he missed because he’d found a flea while scratching his flank and was killing it between two chipped claws, then she turned to the table. She pulled the cardboard box over, slit the packing tape with her nail file, took out one of the twelve-ounce boxes of porridge mix. She poked a small hole in the side, poured out a little in her hand, tasted it, nodded. It was just right. Rubbed the gritty residue on her gums.

Then it all went south.

She repacked the box and looked up, and Papa Bear was showing her a revolver, blued steel, six-inch barrel, pearl grips. He still looked amused.

“Sorry, girlie. I forgot I got someone else coming to pick up that case. Must have slipped my mind. Early spring, you know? Things are still kind of muzzy.”

She stared at the gun. All she could think was she didn’t care about the porridge, didn’t care about the money. She’d hand it all over, but didn’t want to take a wrong step and make Papa Bear think he’d sleep easier with her in permanent hibernation. If Stevie got mad about losing the money, she’d hit him with a rake. Later. Right now, focus.

“Just take the money out and put it on the table, sweet thing, right there,” said Papa Bear. She did it. Then as she zipped up her purse, she saw his look change a little bit, get sharper and softer at the same time. He motioned with the gun.

“I think I deserve a little bonus, honeybunch. Haven’t had me any cuddle time with a sweet young thing like you in too many years. It’s just been me and the fat, hairy missus. How about you and me retire to the backyard…”

But Goldilocks was watching Mama Bear over his shoulder. While Papa Bear talked, she had stopped stirring the pots on the stove and turned to look at him, her eyes squinting and her furry jowls trembling. When he saw Goldilocks’ eyes widen, looking over his shoulder, he turned his huge head just in time to meet the hot iron skillet Mama Bear was swinging at him. Burning grease and carrots flew past him, and Goldilocks went for the floor, tripping over a cub-sized chair and breaking it.

Papa Bear was down, and Mama bear kept whaling on him with the skillet, growling and snarling. Goldilocks grabbed her purse, got to her feet on the grease-slick floor, and was out the back door.

Looked like Mama Bear had picked up a few words of English after all.

***

A month later, she and Stevie drove to a furniture store in Ann Arbor. Now she was living with him pretty much all the time – still had her little place near campus, but more of her toiletries were in his bathroom than in hers now, and she figured that indicated something. He’d handled the Papa Bear incident just right; didn’t care about the money, or said he didn’t, just made sure she was okay and apologized over and over.

They parked in the lot and got out. Walking in, he asked if she’d heard the news about Papa Bear.

“You mean, after he got out of the hospital?” she said.

“Yeah. I guess some cops came and hooked him up just as he was leaving. Someone had called anonymously, said they’d seen him hanging an elk in his garage, no tags. Cops got there, searched the place, found two hundred kilos of high grade durum behind the furnace. He swore it was Mama Bear’s. Said everyone knew she came from a big semolina family. But you know she took off back to her parents right after you were there – extradition from that country’s practically impossible. He took the whole weight himself, federal time. In ten years he’ll get paroled out to a cage in a New Hampshire tourist trap, dancing for leaf peepers.”

“Huh,” Goldilocks said, looking at him. “Wonder who that anonymous caller was.”

Stevie chuckled as they approached the beds. A bright-eyed young man in a cheap blue suit hurried over, held out his hand and introduced himself. While Stevie took the back-slapping sales pitch, Goldilocks walked down a row of beds, poking mattresses. Then she stopped and lay down on one. She closed her eyes for a minute. When she opened them, Stevie was standing over her, giving her that smile, his hands on his hips.

“What do you think? Is that a good one?”

“Yeah,” she said. “This one’s just right.”

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "Elmore Leonard: An Homage in Three Bears"