Scale remains a defining factor in the current age of scholarly publishing. Economies of scale are driving the consolidation of the industry under a few large players and pushing toward an end to the small, independent publisher.When we think about scale, we tend to think about big, commercial publishers gathering together thousands of journals, but there are other ways to achieve scale in scholarly publishing. Megajournals (and entire publishing houses) are tapping into economies of scale by decentralizing the editorial process. The benefits of this decentralization, however, come with costs, at least in terms of quality control and filtration.

The economic benefits of scale for publishers are obvious, as you pay lower prices for services, materials and personnel when you buy in bulk. Consolidation is the state of the market and the big publishers keep getting bigger, benefiting more and more from the resulting scale. But scale also tends to exacerbate the complex nature of journal publishing platforms and processes. We saw a good example of this complexity last year when a society-owned journal moved from publishing with Wiley to publishing with Elsevier, and some articles that were meant to be open access were not immediately made so. When even a single journal moves to a new platform, there are often countless moving parts with which one must deal. When working with this level of scale, things fall through the cracks, mistakes get made, and hopefully, over time, corrected.

There are, however, other approaches to scale beyond just being a really big publisher with lots and lots of titles. Some of the more interesting experiments in the journals market have been geared toward decentralization, that is, looking to benefit from scale by spreading the editorial work of the journal (or journals) broadly. PLOS and Frontiers have both had success with these approaches, but both have also recently had setbacks showing some of the cracks inherent in ceding editorial control to thousands of independent editors.

PLOS ONE is, without a doubt, the greatest success story in journal publishing for the current century. What started as an experiment in trying a new approach to peer review turned out to fill an unserved market need. It has been successful enough to carry the entire PLOS program into profit, freeing it from relying on charitable donations. But publishing 30,000 articles (and with rejections, fielding at least another 10,000) presents a major editorial challenge. How do you handle that many articles? PLOS, at least according to their 990 declarations, has approached this problem via an enormous amount of outsourcing. The outsourced functions most strikingly include hiring third party managing editors through firms offering such services. These outsourced managing editors are responsible for making sure submissions are complete and coordinating peer review.

But that only covers the administrative parts of article handling, what about editorial decision-making? PLOS ONE has some 6,100 editors. Rather than funneling everything through an Editor in Chief, the peer review and decision-making process is spread broadly. These editors “oversee the peer review process for the journal, including evaluating submissions, selecting reviewers and assessing their comments, and making editorial decisions.” But even with that many editors on-hand, a journal as broad as PLOS ONE still runs into occasional issues with editorial expertise. It is harder and harder for everyone to find good peer reviewers in a timely manner and the sheer bulk of PLOS ONE sometimes leads to papers being handled by editors without expertise in the research covered.

Without a central point where “the buck stops,” the quality of the review process can be quite variable. Mistakes are made, such as the recently published “Creator” paper with this sentence in the Abstract, “Hand coordination should indicate the mystery of the Creator’s invention.” The authors claimed that this was a mistranslation (they are not native English speakers) and the paper was subsequently retracted.

Let’s be clear — this was not a typical paper, and the vast majority of what PLOS ONE publishes is rigorously reviewed to meet the journal’s standards. But without the Sauronic Eye of an Editor-in-Chief to enforce standards and provide quality control, you’re going to run into papers where someone took a shortcut, didn’t quite do the work, or has an agenda beyond the journal’s stated vision for publication. There is no consistent level of quality control because there are 6,100 different sets of standards being used and no central point where they come together.

Frontiers, the open access publisher, has seen its own share of controversy lately. They were recently declared a “predatory publisher” by Jeffrey Beall, and journalist Leonid Schneider has written extensively about their various issues. Like PLOS ONE, Frontiers has recently had their own nonsense paper published and retracted, and this is part of a larger pattern where the behavior of the publisher’s 55,000 editors (covering 55 journals) is incredibly varied as far as how well it upholds the stated standards for publication.

I don’t think the term “predatory” is accurate for Frontiers, which continues to run some superb journals. The problem is not that Frontiers is making a deliberate attempt to deceive, rather that there is simply an institutional structure that makes quality control very difficult. The editorial strategy chosen by Frontiers is oriented toward crowdsourcing and away from careful curation and scrutiny. When one deals with such large quantities, you get into bell curves and averages. Some of the 55,000 editors are very good at their jobs, others not so much. As with PLOS ONE, a broad net is cast for editorial talent, and the resulting performance is wildly inconsistent.

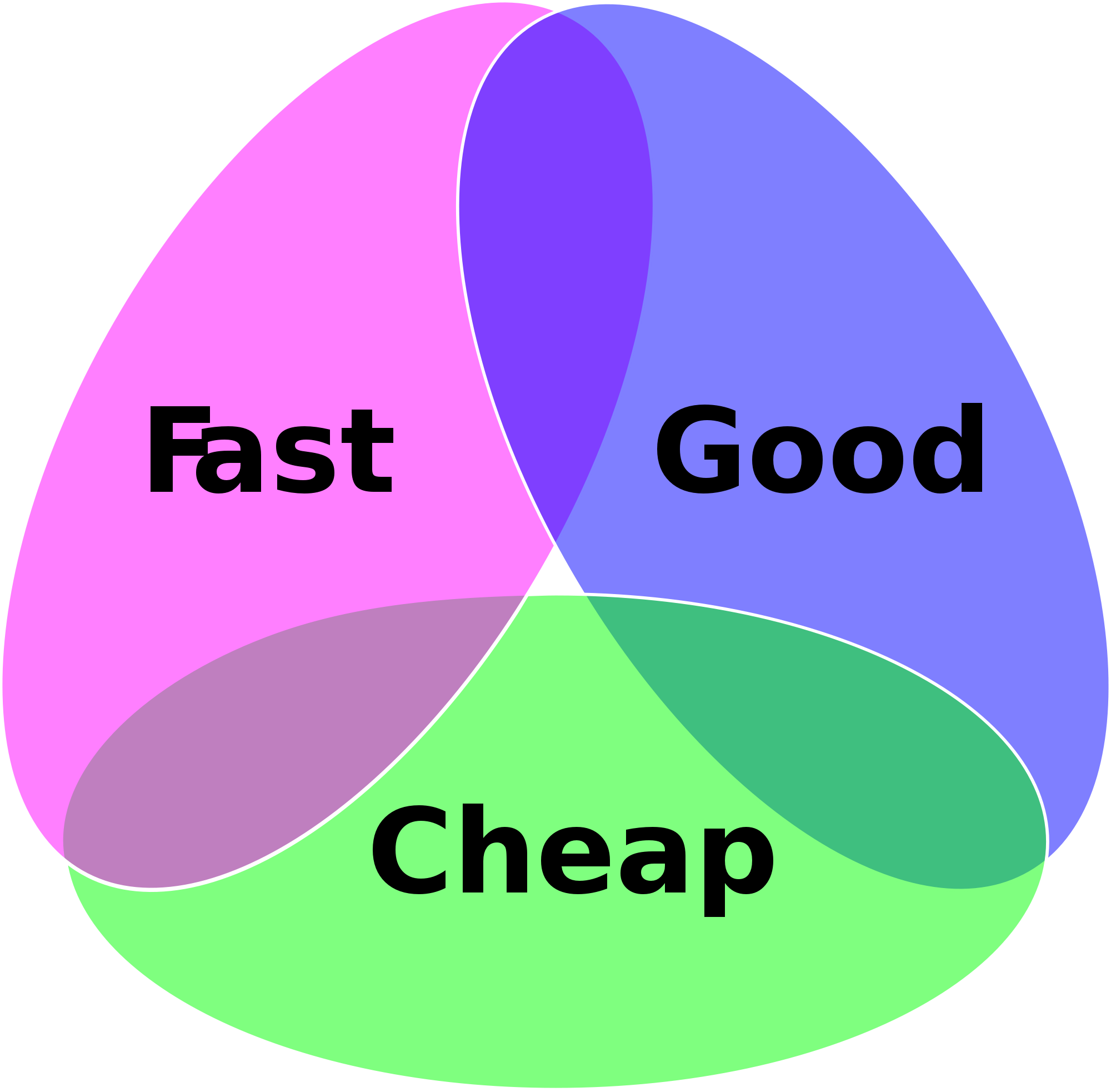

Crowdsourced editorial management is a deliberate strategy — it cuts costs and likely speeds the review process. The gospel of digital disruption has supposedly taught us that the “good enough” product usually wins over the high quality (but more expensive to produce and higher priced) product. The question that must be asked then, is whether these decentralized approaches are “good enough” for the research literature? Is the success to failure ratio acceptable? Given the bulk of the journals in question, do we even have an accurate picture of the success to failure ratio? The Creator paper sat around for two months before a prominent blogger happened to notice it and fired up the internet’s outrage machine. What other timebombs are lurking in the enormous archives of these publications?

All journals make mistakes and have to issue corrections and retractions, to be sure, but are we willing to accept mistakes that are due to a fundamental lack of oversight, with no one really checking to see that the article was indeed properly reviewed (or reviewed at all)? From a psychological perspective, it sometimes doesn’t even matter if your ratio of quality to mistakes is 5000 to 1, if that one case is egregious. The PLOS ONE editor who let through a sexist peer review comment suggesting that a paper could have benefited from a male author made front page headlines and really harmed the journal’s brand. Put another way, it takes years of hard work to build a reputation for quality, but quality is a very fragile attribute and can be destroyed quickly when something like #CreatorGate surfaces. One prominent researcher went so far as to declare the journal “a joke”, wiping out years of reputation building.

Validation is a key service that journals provide, which is endangered by decentralization. Another key offering from journals is filtration:

…the reputations of journals are used as an indicator of the importance to a field of the work published therein. Some specialties hold dozens of journals—too many for anyone to possibly read. Over time, however, each field develops a hierarchy of titles…This hierarchy allows a researcher to keep track of the journals in her subspecialty, the top few journals in her field, and a very few generalist publications, thereby reasonably keeping up with the research that is relevant to her work.

Ask any researcher in any field and they can tell you the journals which publish the best work that is most relevant to their own research. When faced with an enormous stack of reading, it’s really helpful to be able to prioritize, to know which papers to read first. A good Editor-in-Chief or Editorial Board sets a clear standard for quality and gives a journal its “personality”, which can enable that sort of filtering. When you have 1,000 independent editors each following their own set of rules, the personality of the journal gets diluted, if not lost altogether, and the researcher loses a valuable tool.

Given the numbers of papers published through such decentralized approaches, there is clear market demand for the services these journals offer. But when one looks at the furor that arises around these sorts of blatant editorial errors, it is clear that mistakes of this sort are unacceptable to the community. Editors have a solemn responsibility to strive for quality in all efforts, and a journal’s reputation is based on someone setting standards and consistently enforcing them. Turn that over to a crowd of editors and the resulting articles are likely going to be all over the place. Does reputation still matter? Is this “good enough” for the scholarly literature?

Discussion

25 Thoughts on "The Downside of Scale for Journal Publishers: Quality Control and Filtration"

I’m fascinated by the “Outrage Machine”. I wonder to what extent it has an effect in reality. 140 chars over a glass of wine is easy. I wonder how far it actually penetrates. Like the articles that lie there waiting to be read, I suspect that most folk will only perceive of these papers dimly, if at all.

I also wonder how one squares the approach of the mega journals (eg PLoS) with the whole reproducibility issue. If you crowdsource the standard setting (and it’s a perfectly valid approach!) then surely that acts in opposition to any attempts to get higher ‘reproducibility’ across a given field of study. Because there will always be an outlet for that poor quality paper.

I expect that the phrase “Post Publication Peer Review” will show up as a solution to the issue. Problem is, that’s just another word for crowdsourced quality control isn’t it…

David, you pose a reasonable question but is the rate of documented serious errors/retractions that much higher than in traditional publishing? Even the most prestigious journals have their share of retractions. These journals publish a very large number of articles so is there a higher error rate in the review process or just more errors because so many articles are published. I don’t know the answer but I think it is a fair question.

David Crotty’s point is that it doesn’t matter what the ratio of quality:failures is when it comes to brand perception. High-profile retractions like the Hand-of-God paper have people question whether anyone even read the abstract; and controversies about sexism have people question whether the editor understood his/her role in the review process. With so much of the publication process black-boxed, instances like this have people question what is going on inside that black box, and whether anyone who oversees those black-boxed processes knows what’s going on or even cares. Trust is a fragile attribute, taking years to build but shattered very quickly. An automobile engineer might be concerned about quality:failure ratios, but everyone else really cares about whether they can trust what happens when they put their foot on the brake.

There could also be a lower rate of retractions because there is less scrutiny of papers in journals like PLOS One. I agree it’s a fair question, but getting an answer is more difficult than you might hope.

I worry more about fraud in low-profile journals and less-spectacular discoveries. If you claim human cloning or fabulous breakthroughs in organic semiconductors, OF COURSE you’re going to be caught. Thousands of people will read those papers, hundreds of labs will be looking to replicate. The hidden problem is fraud in small ways – where detection is less likely and you have a small contamination that may never be surfaced.

David: Your argument was tried by myself in traffic court. I was a traveling book rep and got a ticket. I said to the judge that because I drove more I was more likely to be caught to which the judge replied then don’t speed!

Regarding Plos – If memory serves they only review to see if the paper is technically sound. Does that mean that I can take a paper from Plos and rewrite it and because it is technically sound it would be published.

I’ll echo Phil’s comment above, that quantity may not matter as much as quality. The nature of the error may be more important than the number of errors. Nature and Science have a reputation for seeking to publish groundbreaking, sexy research, and when they screw up, it’s often a case of overreach. That has a very different effect on the journals’ reputation than high profile cases where the problem is one of sloppiness or an editor going rogue and publishing his own unreviewed work. Each will effect how one approaches and reads the journals in different ways.

There’s also likely perceptional issues with quantities versus ratios. If journal A publishes a small number of issues with a small number of articles and has one bad article, their success/failure ration may be poorer than journal B that publishes tens of thousands of articles per year. Yet the bigger journal may have more bad papers in a given year, giving the perception that there is a constant flow of incompetence, even though the actual ratio outperforms the smaller journal.

So as stated in the post above, I’m not sure quantitative measures can truly address what is a qualitative response.

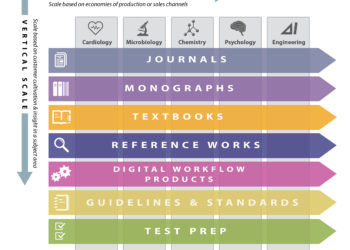

In other sectors of publishing where consolidation has occurred–trade publishing (where the major players are now just five) and college textbook publishing (where they may now be down to four)–there seems to be no counterpart to the PLoS phenomenon and the filtering problem.

Since a single example of editorial oversight is apparently enough to condemn PLoS’s decentralised approach, presumably this counterexample proves that the “Sauronic Eye of an Editor-in-Chief” doesn’t work either: https://twitter.com/Neuro_Skeptic/status/711970614685409280

Or perhaps these (thankfully very rare) oversights can and will happen under any system?

The post was not meant to catalogue every example of oversight failure, but to provide illustrative examples (more can be found in the links).

However, as noted in the post above, “All journals make mistakes and have to issue corrections and retractions, to be sure.” But the one you point out is a different kind of mistake–the paper may actually be scientifically valid, and if so, then the screw-up is in plagiarism detection, which is more of an administrative task than peer review. Some journals go to the trouble and expense of running detection software, others don’t bother. From your comment, it sounds like this is a level of scrutiny you would like to have performed in all journals, and I assume you’d be willing to help support the costs.

Even so, this does damage the reputation of the journal in question (the God reference should not have been allowed in), but at least in the case of this journal, there is an editor-in-chief who can be held accountable (http://www.journals.elsevier.com/renewable-and-sustainable-energy-reviews/editorial-board/) as opposed to just shrugging off the error as something that happens in a distributed system.

My understanding is that the PLoS ‘hand of god’ paper *is* scientifically valid (based on what others have said – not my field), and the objection was only to the ‘creator’ reference. So then, leaving plagiarism detection aside, we have basically the same peer review fail: the reviewers/editors didn’t notice or didn’t object to a prominent invocation of a deity.

Not my field either but I have read critiques of it that it was basically an odd thing, essentially descriptive of hand structure, rather than adding any new knowledge. But I suppose that’s acceptable under the rubriq of “methodologically sound” (but also affects journal reputation).

I suppose the difference between the two papers is that the PLOS one attributed the phenomenon being described to the direct action of a divine being, whereas the other used it more as a figure of speech or at worst an anthropomorphization (note that in the plagiarized version, the “gift from nature” is just as problematic).

Regardless, the EiC of the journal should be taken to task here for doing a bad job, and the journal’s reputation should suffer. What’s fair for one is fair for the other, but we shouldn’t give PLOS a pass and let them excuse what happened because the editor was working on a subject beyond his expertise (https://forbetterscience.wordpress.com/2016/03/04/hand-of-god-paper-retracted-plos-one-could-not-stand-by-the-pre-publication-assessment/) or that he’s just one of 6,100 editors and stuff like this is going to happen. Those are structural flaws in the system. The problem isn’t that there was someone who was supposed to check this stuff and they failed to do their job. The problem is that there is no one to check this stuff.

As a scientist, I have a hard time following arguments that are exclusively built on examples (i.e., anecdotes). In this particular post, examples are selectively picked from ‘mega-journals’ to claim (quite correctly, one might say) that “mistakes of this sort are unacceptable to the community”.

Now let’s randomly pick two similarly egregious examples of lack of editorial oversight, one where the authors (English native speakers) claim three times in the same paragraph that the fruit fly, Drosophila, is not an animal:

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0092867415002421

and the one cited by Fluorogrol:

https://twitter.com/Neuro_Skeptic/status/711970614685409280

Both are likely as scientifically valid as the #creatorgate paper (as far as one can tell for now) and both are likely equally superficially reviewed/edited. However, neither of them has – so far – generated quite such an emotional reaction.

Like David Crotty wrote: “All journals make mistakes and have to issue corrections and retractions, to be sure.”, so to cherry-pick anecdotes to try to illustrate that one sort of journal has some ‘quality’ issues as opposed to other journals can not really ever be all that convincing, as one can find such examples in any journal to make any ‘quality’ argument, depending on persuasion/preference. If you want to make a quality assessment, you’ll need to define what you mean by it, quantify it and show reliable differences. Everything else amounts to nothing but hot air.

If you define one form of quality as methodological soundness (i.e., how likely is it that any given paper will be scientifically valid), then the most prestigious journals publish the lowest quality work:

That’s the kind of evidence you’d have to show, if you wanted to make a quality-related claim readers ought to be inclined to believe.

However, there is something that one can use such anecdotes for: to illustrate that the same transgressions often lead to completely different reactions by the scientific community: a new journal screws up a little, once, and is called “a joke”. A more prestigious or at least more established journal screws up big time repeatedly over years and every single time the community briefly looks up to ask “how could this get published in such a great journal?” and then goes on to completely forget about each event.

The only thing the examples David Crotty picked serve to illustrate, is the fickle nature of human judgment and how subjective notions of ‘reputation’ are rarely affected by evidence, but rather by other social and psychological factors: one paper with a mistranslation and the journal is a ‘joke’ and a long string of one fraudulent coldfusion/stemcell/cancercure after another and nobody cares. In this case, David Crotty’s examples indeed illustrate such well-documented observations.

Therefore, David Crotty is correct (albeit perhaps not in the way he intended) to ask “Does reputation still matter? Is this “good enough” for the scholarly literature?”

The data we have until now are quite clear: if scientific validity is what you define as ‘quality’ then journal reputation has completely ceased to matter: the more such reputation a journal has, the less scientifically valid its works are, on average. This entirely subjective “my-buddy-publishes-his-best-stuff-there” reputation is not even in the ballpark of “good enough” – especially not for a community that calls itself ‘scientific’.

To me as a scientist, it is quite embarrassing that we do the equivalent of swinging our divining rods over journals to assign reputation. And to add insult to injury, this method is even more pernicious than chance.

Whether OA or subscription, traditional or “mega” all journals are dependent on a system of trust and reputation. Journals trust authors to submit an accurate report of work conducted; authors trust journals to treat their report ethically; editors trust reviewers to be the first and most attentive readers; reviewers trust editors to use their contribution appropriately; readers trust all of the above to filter, sort, and generally improve the quality of the corpus itself. And there are more layers of trust as the number of members of this system increase. Publishers, aggregators, metrics providers…everyone trusts everyone because each player’s reputation is on the line.

This system is designed to construct the scholarly edifice – it is not designed to build a defensive fortress. By its design, scholarly publishing is inherently susceptible to deliberate fraud. This susceptibility is made worse as the scale of the system increases, and as the responsibility becomes more dispersed.

Our choice is this: Do we want a fortress? How much contamination is tolerable in the system, generally, or in any outlet, individually? Do we trust the system to detect and correct if we have “good enough” filtration on first input?

I am generally of the opinion that we need to be vigilant, but not paranoid; we need to sanction rather than police. Most of all, transparency of process, and of problems, should be seen as a positive action by author, editor, publisher, reader.

Marie: Good points and a most valid argument. It seems to me that there are those who want to game the system and who have a personal mission to discredit the scientific publishing community. Who commit an act and then sit back and say: See I told you the system has feet of clay.

I find your analysis a most compelling one and think that when an event occurs the Journal should point it out, retract and state that it was gamed.

This is an important conversation to be having, and when we think about quality relative to cost, whether driven by scale, prioritization of resources, or otherwise, I wonder if there are differences in either perceptions or thresholds relative to those costs. Does the average reader or author expect or tolerate a lower level of quality from a relatively inexpensive open access journal than from a “high-priced” subscription journal? In the #CreatorGate example, the problematic sentence should easily have been noticed and corrected during the post-acceptance stages of a traditional publishing process, i.e., copyediting and proofreading, and not just by the handling editor. But when “good enough” is the paradigm and resources for performing and/or overseeing those functions are diminished or cut, quality inevitably suffers. I’m not familiar with how those functions are managed in decentralized systems or what role they might have played in #CreatorGate, but the broader point is that when we neglect quality control functions for the sake of reducing cost, there is an inevitably higher risk for error and damage to reputation – not to mention the difficulty of credibly answering the voices that ask “What do publishers do?” and “Why are publisher’s necessary?” When single examples of error take full-time residence in memory, pushing out the overwhelming examples of accuracy, is diminished attention to quality control something we can collectively afford?

Allison well said. An example that is far afield is that of the US auto industry. It just now starting to compete again! A bad image is hard to repair

Poor quality control can occur even in the most prestigious of places. Take this set of articles for examples of unscientific nonsense from a Nature-branded platform:

http://www.natureasia.com/en/nindia/article/10.1038/nindia.2012.80

http://www.natureasia.com/en/nindia/article/10.1038/nindia.2012.89

http://www.natureasia.com/en/nindia/article/10.1038/nindia.2012.105

Excellent post, David, but what do you mean by “the gospel of digital disruption”, which has “taught us that the “good enough” product usually wins over the high quality (but more expensive to produce and higher priced) product”? By all means suggest that journal editorial standards are under threat by new publishing paradigms such as PLOS ONE, but to suggest that this is yet another example of “the gospel of digital disruption” extends your argument dramatically. Are you saying that all recent errors in journals (and even PLOS ONE, albeit on a much larger scale, is still edited and reviewed by humans) are the fault of IT developers and their new business processes? That’s quite a transfer of blame!

Sorry if I wasn’t clear. What I was talking about is the culture of “disruption”, best epitomized by the theories of Clayton Christensen:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disruptive_innovation

I used the phrase “digitial disruption” because this philosophy is the driving force for many online and digital businesses, particularly in our industry. The notion is that a cheap, “good enough” product will drive the current market leaders’ higher-priced, higher-quality products out of business. The question I’m asking is if this is truly the case here, or if this market demands a different standard.

We know that many new journal offerings are deliberately streamlined, less editorial oversight, lower standards for acceptance (methodological soundness, not significance), many do away with services such as copyediting and the like. This fits in well with the philosophy of disruptive innovation.

And yes, I do think that many of the errors described above can be attributed to the design of the systems that have been put in place. There is a deliberate decentralization, a move toward crowdsourcing rather than centralized authority, a move toward cheaper, “good enough” services. I wouldn’t place the responsibility for this on IT developers but would on the new business processes and the philosophy behind many of them.

I’d like to suggest that these discussions of quality and reliability in bio-medical science publications are most relevant to people who look to journals for scientific “stories,” or authors who are scratching for credibility in an ever-shrinking academic job market. For the rest of us, the disruption has already arrived. In my professional life, scientific journals serve a less glamorous purpose, acting as a repository for primary data often only indirectly related to the flashy “breakthroughs” so prominently on display in high impact journals. Prestige journals are more often source of entertainment, something to read while relaxng in my hammock, sipping aged rum on a Summer night.

As an industry scientist, I mine the literature every day seeking valid, quantitative values that inform physiologically-based mathematical models. It is rare to find truly useful and reliable quantitative data in reports published in prestigious journals. “Space limitations” and distracted or unqualified peer reviewers seem to assure that key details are excluded or poorly vetted in high profile reports, making them fairly useless to me.

Regardless of their source, the snippets of published data that underlie my daily work are most useful for establishing boundary conditions, and enable me to focus my wet lab experimentation on the most critical factors at hand. The more often a similar theme is repeated in the literature, particularly in much derided “specialty journals,” the higher my confidence in those results, making “high impact journals” even less necessary. In my opinion, the increased adoption of predictive modeling and readily accessible text- and data mining software in biomedicine represents a sea change that editors will ignore at their peril.

A copyeditor would have caught that hand-of-God reference. But NOBODY wants to pay copyeditors these days. The publishers perceive that copyediting has value, but its cost is higher than the value the publishers perceive.

There certainly can be a downside to rapid expansion of commercially published journals. For example, from a recent blog posting: “I served as one of a group of guest editors for a special issue of a Hindawi journal. We got very poor service from the journal, e.g., articles were lost by them or routed to other journals or rejected before we saw them and without telling us. After our complaints they changed staff members for us twice but with no improvement. Also authors were not told of the publishing fee until after papers were accepted. I would not work with them again in this role and am unlikely to submit a MS to any of their journals.”