The American College of Chest Physicians recently announced it would be ending decades of self-publishing: its well-known journal CHEST will soon be published by Elsevier. A society with a single journal deciding to throw in its lot with a large commercial publisher is not atypical, and for many such societies this is a sound decision. A small society publishing program cannot muster the economies of scale around production, technology, and (most important) institutional sales that can be brought to bear by a large publisher.

That larger publishers are able to develop greater economies of scale is, of course, no surprise. What’s surprising is not how many society-owned journals are published by commercial publishers (I include Oxford and Cambridge university presses in this camp in terms of size), but rather how many remain independent. Why is this the case? One factor is that many society journals (and university presses) were established before commercial publishers were significant players in the scientific, technical, medical (STM) and scholarly marketplace. It was only following World War II that commercial publishers began steadily increasing market share, and it was not until quite recently that these scale effects began to exert a deleterious influence on independent societies (a topic which has been touched on before in the Scholarly Kitchen, most directly by Kent Anderson in this piece from 2013).

If you are a society that has been self-publishing for many decades, such effects may appear as only a recent headwind in a long publishing tradition. This headwind, however, is most likely not a temporary zephyr but rather a permanent fixture of the STM and scholarly publishing landscape, and one that will only increase in intensity.

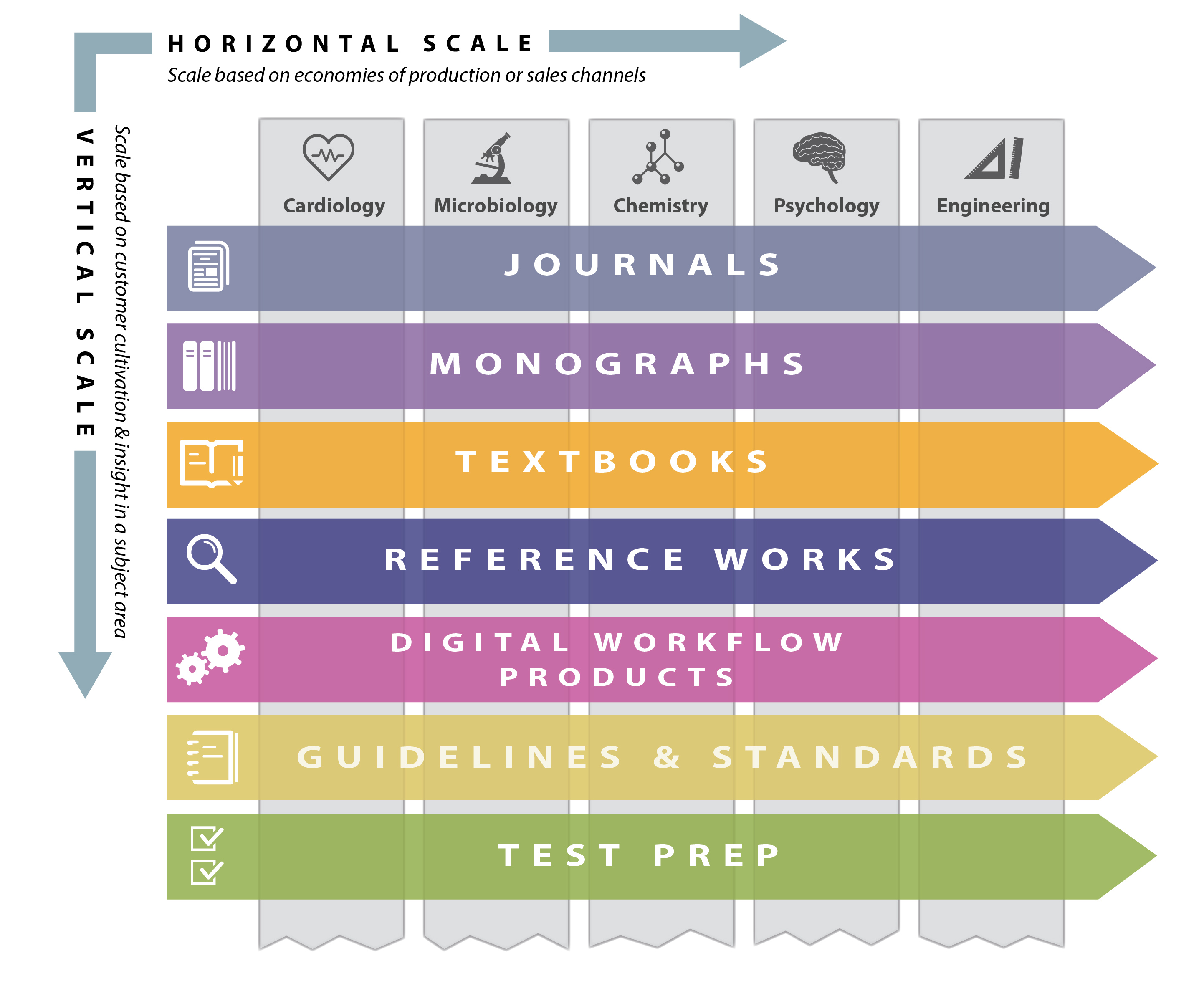

To understand why, it is helpful to look at the two vectors on which scale operates in STM and scholarly publishing: horizontal and vertical. While horizontal scale has long been the province of commercial publishers, society publishers are typically organized to take advantage of vertical scale. The headwinds are presently blowing along the horizontal plane, from the perspective of the society publisher.

Horizontal scale focuses on the economies of scale that come with producing large numbers of the same type of product. Horizontal scale is oriented around production and distribution. Large commercial publishers produce and distribute thousands of books and journals annually across many different subject areas. Although some commercial publishers have areas of emphasis, they generally publish across many disciplines. A single publisher might publish books and journals in fields as diverse as cardiology, microbiology, chemistry, psychology, engineering, business, and law (see Figure 1 below). By publishing across many fields, a publisher is able to develop economies of scale around production (XML markup, copyediting, composition, metadata enrichment), infrastructure (submission systems, content management systems, production systems), dissemination (platform hosting), and institutional sales.

Vertical scale focuses on the economies of scale that come with selling different types of products to the same customer base. Vertical scale is oriented around marketing. It is “vertical” in the sense that marketing professionals refer to sectors or niches in the market as “market verticals.” In STM and scholarly publishing these market verticals are well defined. They are organized around fields of study or practice and typically are represented by professional associations to which many members of the field belong. A medical specialty association, for example, might produce not only journals and monographs but also myriad other products and services focused on the needs of their members (see Figure 1, below).

Take the example of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), where I once worked. The AAP publishes a primary research journal and several review journals, a news magazine, a number of reference books, a textbook, numerous monographs, and hundreds of regularly updated clinical practice guidelines. It also produces digital workflow products related to practice management (AAP Point-of-Care Solutions) and the management of continuing education credits (PediaLink). It further produces a number of online continuing education products, including materials to help physicians with maintenance of certification. It organizes and produces dozens of meetings annually, including a large annual conference and exhibition. All of these products and services are developed around the needs of pediatricians, about which the association knows a great deal and with whom the association has deep and longstanding relationships.

By and large, this vertical scale strategy has worked well for associations and societies for a long time. What independently published associations have historically given up in horizontal efficiencies with regard to production costs related to journals and books, they have gained back in vertical efficiencies such as marketing and individual sales. The shift in the importance and nature of institutional sales has, however, changed this dynamic in a number of ways.

1. Decline of the individual subscription. Until the late 1990s, library sales were not a large source of revenues for most society publishers. Prior to electronic journals, most revenues related to society journals derived from individual subscriptions. Medical associations in particular also realized (and continue to realize) substantial revenues from commercial reprints and advertising (mainly from pharmaceutical companies). But the lion’s share of revenues remained with individual subscriptions, usually paid in the form of membership dues with a smaller number of non-member individual subscriptions. (When I began work at the AAP in 2002, institutional subscriptions were not even broken out in financial reports, and were simply grouped, along with numerous individual subscribers, under “non-member subscriptions”). Institutional subscriptions were designed for the library reading room (later being bound into volumes for the stacks) and were typically priced from fifty to one hundred percent more than an individual subscription.

Individual subscriptions have been in decline for decades. But with the advent of site licenses and the Big Deal, this erosion accelerated, as individuals could now obtain online journal access right from their office or wherever else they might be.

Carol Tenopir and Don King have long tracked reading trends in scholarly information via an ongoing longitudinal analysis they have updated regularly for decades. Their latest installment, published last month in Learned Publishing, reports that:

Articles obtained from personal subscriptions decreased from 60% in 1977 to 53% in 1984, down to 35.5% by the early 1990s.This decline has continued – only 18% of article readings in 2012 are from personal subscriptions.

Tenopir and King are tracking readings, not subscriptions, but because they have tracked the source of readings, their data paint a clear picture of a trend that is corroborated by the individual subscriber records of scholarly publishers, which also show declines. This downward dynamic resulted in a shift in importance from individual to institutional licenses and a concurrent rise in institutional pricing. From the perspective of the library, prices began to rise dramatically. From the perspective of the publisher, however, revenues (and usage) shifted from individual subscriptions to institutional licenses, which took on increased importance.

2. Decline of subscription agents. Prior to the advent of site licenses and the Big Deal (the bundle of electronic journals, and increasingly books, that publishers sell to institutional customers, such as academic libraries) , the vast majority of institutional subscriptions were processed by subscription agents, which provided economies of scale to small and large publishers alike. With the rise of the Big Deal and the increase in library consortia, site licenses increasingly have been negotiated and sold directly by the publisher. Defunct subscription agents like Swets and RoweCom are the collateral damage in this transition. Few subscription agents remain, with EBSCO being the most prominent (Japan, where three subscription agents continue to serve the market, is an important exception).

A new kind of independent sales agent (e.g., ACCUCOMS, iGroup, Publishers Communication Group) has emerged to help provide a global footprint to independent publishers. The difference between the new agents and the old ones is that the new agents are much smaller and are focused almost exclusively on negotiating site licenses, whereas the old subscription agents were more focused on library services, distribution, and payment collection. The new agents represent many independent publishers and have been able, to an extent, to re-create some of the economies of scale that came with the old subscription agent model. That said, working effectively with agents requires a certain amount of internal resourcing and expertise that many small society publishers simply do not have.

3. Increased bigness of the Big Deal. Because institutions have limited budgets, the best way, as a publisher, to increase the odds of success of any package is size and quality (but mostly size). Have enough “must-have” content in your portfolio and you will be, well, must-have. Become a large enough portion of a library’s holdings and you become “too big to cancel” (TBTC). TBTC has driven many of the mergers and acquisitions in recent years, including Wiley’s acquisition of Blackwell, Informa’s acquisition of Taylor & Francis, and the just-completed Springer-Macmillan merger.

Societies, by their nature, rarely merge or acquire other societies, and when they do it is usually driven by structural changes in the field as opposed to publishing considerations. Society publishers have, however, formed alliances of various types to create larger packages. Examples include BioOne, GeoScienceWorld, JSTOR, Project MUSE, the Independent Scholarly Publishers Group, and the ALPSP Learned Journal Collection. These efforts have met with varying levels of success but all suffer from the problem of needing to optimize revenues for each publisher in the collection. Each publisher has different levels of market penetration, different target markets, and different pricing. Aggregations will necessarily optimize for the aggregation itself, which does not always benefit each participating publisher. An equally challenging problem is that none of these collections (with the possible exception of JSTOR, if one includes its archives) has enough mass to compete with the gravitational pull of the largest commercial houses.

Membership Model Implications

Associations offer a variety of benefits to individuals in the form of products and services. These might include complimentary journal subscriptions, discounts on meeting attendance, books, educational materials, networking events, and other discipline-relevant products and services. In some cases, membership in a professional association acts as a kind of credential for the individual. These various products and services are bundled together in an annual membership fee paid to the association.

The membership model is a package oriented around vertical scale. What the Big Deal is to horizontal scale, member dues are to vertical scale. Critical to success of the membership model is that it includes enough benefits other than journals that individuals are willing to pay for. This is because individuals are increasingly able to access journals via institutional site licenses. If the association’s membership package does not include enough benefits beyond the journal, site licenses will cannibalize memberships.

That membership has not collapsed with the advent of institutional site licensing and the Big Deal indicates that members, by and large, are finding continued value in the membership package beyond journals. This has enabled society publishers to optimize for both vertical scale (via membership dues) and horizontal scale (via site licenses). Although this balancing act between these two vectors of scale continues to hold for many associations, it is a delicate position. Factors such as the age of its membership, the reach of its site licenses, and the strength of its other member benefits will determine, for each association, how long the balancing act will hold.

Open Access Publishing and Scale

Author-pays or “gold” open access (OA) publishing has become increasingly prominent over the last few years, as a recent Outsell report notes (a discussion of this report can be found here). Early on, as momentum around this business model grew, I thought that OA would naturally play to the vertical strategies of association publishers. After all, associations and societies are closest to authors – their members – and open access is all about marketing to authors. As it turns out, I was wrong (when was the last time you heard a consultant say that?).

While there are examples of successful OA publications from society publishers, commercial publishers along with the Public Library of Science (PLOS, which is a not-for-profit but not an association) publish the vast majority of OA papers. OA publishing turns out to be a model that benefits more from horizontal than vertical scale effects. There are several reasons for this:

- Volume. OA business models are only economically viable with a substantial article volume (or a very high article processing charge, or APC). The volume required for viability varies based on the APC, of course, but generally speaking OA publishing compels a much higher volume than a subscription model. For example, according to Web of Science, Nature (a subscription journal) published 848 articles in 2014. That same year, Nature Communications and Scientific Reports (two OA journals from the same publisher) published 2,781 and 3,929 articles, respectively. PLOS ONE, the ne plus ultra of OA titles, published 31,480 articles in that same timeframe. Publishing the same format of thing (articles) at volume is a horizontal play, something commercial publishers (and PLOS) are generally much better at than associations (the notable exception here being The Optical Society, whose Optics Express was the first OA publication to successfully publish at a high volume). Association publishers simply don’t have the experience with volume nor the systems and processes that make volume-based business models successful. They also do not have the ability to create peer review cascades (at least not at the scale of commercial publishers) that can seed new OA publications and continue to supply them with papers transferred from across a large portfolio.

- Quality. A second factor that makes OA publication less suited to associations is quality. Quality, of course, is a slippery concept, but here we mean the traditional markers of quality in scholarly publishing: high production value, careful copyediting, thorough peer review, and the publication of papers likely to attract many (relative to the discipline) citations. These hallmarks are deeply ingrained in the thinking and indeed the mission of many associations and societies and are the markers of quality for a selective publication regime. Talk to editors and publishers at most associations and they will tell you that their mission is to publish the “highest-quality” research in their field. The problem is that these markers of quality naturally lead to low-volume publication models with high costs per article. To successfully operate an (unsubsidized) OA publishing program, a publisher must keep the per-article cost very low. This means lighter peer review, lighter copyediting, less handcrafting in the production process, and the publication of far more articles overall. The markers of quality in OA publication are speed, efficiency, and less emphasis on matters of fit or novelty. Commercial publishers have proven more adept at adoption of OA in part because they are more comfortable with publishing a wide range of articles with different levels of (and definitions of) quality. A publisher like Elsevier has brands like Cell and The Lancet along with many less prestigious brands. They simply have a much bigger tent and know how to manage a wider range of brands, whereas associations are mostly focused on their primary brand: that of the association itself.

- Institutional funding model. While at first blush it seems as if OA publishing is a return to a business model focused on the individual (at which associations are expert), it turns out it is actually an institutional model. APCs are paid by by academic institutions along with research funders, increasingly in the form of a “membership” that looks very similar to a Big Deal but for APCs. In at least one case that may be a bellwether for things to come, APCs and site licensing fees are being negotiated together. As a result, much the same infrastructure and experience that commercial publishers developed to support institutional subscription sales remain an advantage with regard to OA publication.

Unlike other observers, I don’t think there is a conflict between the society membership model and OA publishing – unless societies attempt to migrate their existing journal portfolios to open access. And even then, as noted above, site licensing has already created strong incentives for societies to construct membership models that are not solely dependent on journals.

So does it all come down to scale? Scale effects explain much about the current publishing landscape. It is becoming increasingly difficult to remain competitive in journal publishing without horizontal scale. This was not the case only a short while ago because everyone had horizontal scale via subscription agents – it was not a competitive advantage. The Big Deal and library consortia have transformed the market, providing sustained competitive advantage to those with strong global institutional sales capabilities. It is becoming clear that open access publishing does not run counter to this dynamic but rather reinforces it.

That said, scale is, of course, relative. There are successful societies who, with relatively small publishing operations, command a large enough percentage of the content in a given field to remain indispensable. Physics is perhaps the best example of this, where three societies (the American Physical Society, the American Institute of Physics, and the Institute of Physics) publish the vast majority of the work in the field. In chemistry, the two most important publishers are the American Chemical Society and the Royal Society of Chemistry. In optics, The Optical Society and SPIE are dominant. There are other examples. For society publishers in this position, having just enough horizontal scale may remain a winning strategy.

For independent societies that do not publish a critical threshold of research in their field, the headwinds of horizontal scale will likely remain strong for the foreseeable future. I will explore strategies for tacking against this headwind in a future piece.

Discussion

9 Thoughts on "The Changing Nature of Scale in STM and Scholarly Publishing"

A truly excellent piece about scale! I do think you ignore a major factor that allows society publishers to remain competitive with commercial publishers in spite of their lack of (horizontal) scale—the presence of a very large and diverse 3rd-party publishing services industry. These services industries include online platform providers, manuscript management and peer review systems, plagiarism detection and image manipulation, copy-editing, typesetting, DOI registration, digital archiving, pay-per-view/article rental, PR services, performance metrics reporting…and I’m probably missing many. All of these services are available to the smallest society publisher. Granted, they are unable to negotiate for bulk discounts like a commercial publisher (so they are working against economies of scale), but I can’t think of a service that a small society publisher is denied because they don’t perform that function in-house.

Thanks Phil and you are exactly right. I was focused on the area where independents struggle with horizontal scale, but you are exactly right that there is a constellation of services that provides scale benefits for almost every function outside of institutional sales bundles (except as noted above). This was an omission from my piece — thanks for catching and correcting it (post-publication peer review in action!).

Michael this is a great article and an excellent analysis of the business. It seems to me that what needs to be discussed is cost of publishing for a small society – and all societies are small when compared to the commercial world.

The price of quality is in all the human capital it takes to publish a single journal of quality and the return is just not there. A commercial house can take over the operation without there being a loss of quality and give a 15 to 25% royalty which is multiplied due to the reduction in staff.

One often forgets that a society or association is a business and one that has to make money. Interestingly enough once the society signs the contract with the commercial publisher, and if the transition is smooth, membership does not even realize that the society no longer is the “publisher ” of the journal.

Phil, even though there are service companies, these cost money and eat into the P&L of the society. At some point the society has to ask: Why are we self publishing when it is so costly?

You are absolutely right Harvey. One of the things things I’ve noticed happening over the years is that the larger commercial publishers will invest in many incremental process improvements. They will invest in process improvements or technologies that will shave 1% or less off their production costs. Of course 1% for a commercial publisher is a big number in terms of absolute dollars/GBP/Euros. Smaller publishers don’t focus on these improvements to the same extent because the absolute savings is so small. “Why bother — it is a lot of work to save a very little money.” But over time, those small efficiencies add up and the commercial publishers eventually become significantly more cost effective.

Excellent, excellent piece, Michael. One comment:

Because institutions have limited budgets, the best way, as a publisher, to increase the odds of success of any package is size and quality (but mostly size). Have enough “must-have” content in your portfolio and you will be, well, must-have. Become a large enough portion of a library’s holdings and you become “too big to cancel” (TBTC).

When it comes to Big Deal renewals, it’s important that publishers not kid themselves about the power of package size in and of itself. (In other words, I wholly agree with the first two sentences quoted above and am raising a small red flag about the third.) Let’s say, for the sake of argument, that Publisher X’s Big Deal package represents a plurality of the ejournal titles in my library’s collection. That fact alone does not make it less likely that we’ll cancel the package. What is heavily determinant of our decision is the cost per article download. Cost per download is, of course, significantly affected by package size — but it’s not the same thing. When it comes to individual subscriptions, the moment at which we start becoming likely to cancel is the point at which cost-per-download equals or exceeds the cost of buying a desired article from that journal in response to patron need. The same goes for a Big Deal package. It won’t survive just by containing many titles — it has to contain enough high-demand content to make it a good value on a per-article basis, and we measure value largely in terms of real-world use. The more high-demand content a package shows itself to have, the longer it will live in my subscription list — but we make that determination at the article level, not the title level.

Every instance of “we” in the above paragraph refers specifically to my library. But in the decision-making process I’ve described above, I have every reason to believe that we’re broadly typical of research libraries generally.

Great post Mike, and you’ve nailed much of the business logic behind CHEST’s decision to move to Elsevier as our publisher. The publishing operations and services can be managed by Elsevier far more efficiently due to their ability to realize economies of scale for those services. In addition, as Phil Davis and Harvey Kane note in the comments above, there is an enormous resource burden in managing all of the various independent 3rd party publishing services needed by a small society publisher. So by partnering with them on Publishing services and operations to broaden our reach and visibility through their extensive horizontal scale, we free up resources to continue driving our organization’s horizontal scale and numerous product verticals, as outlined in your Figure 1. If a commercial publisher can take on the publishing resource workload, we can focus on other types and avenues of content development and distribution for our customers.

Quality and size clearly do not always correlate. In fact, the inverse can be true. I directed a smaller university press for 20 years, and quality was a major emphasis–in production, customer service, author relations, copyediting, etc. I’m speaking about both journal and book publishing. What did matter ultimately, for journal publishing, was that we could not afford by ourselves to make the transition to e-publishing successfully, so had to join a consortium, Project Muse. There scale made a huge difference, to be sure.

As for OA, scale makes a difference only for APC-based OA, as you seem to implicitly admit. There are of course other OA models.