Editor’s note: Today’s post is by Hilary Craiglow, Cynthia Hudson Vitale, and Tim McGeary. Hilary leads library consulting at Attain Partners, a higher education consulting firm. Cynthia is Associate Dean for Technology Strategy and Digital Services at Johns Hopkins University Libraries, where she leads strategic initiatives in support of research, teaching, and scholarly communication. Tim is the Associate University Librarian for Digital Strategies & Technology at the Duke University Libraries, where he leads in strategic visioning and implementation of digital initiatives and programs for libraries and their partnerships in technology and research, building internal and external collaborations to create sustainable solutions for scholars and researchers.

Academic and research libraries have long been a cornerstone of the scholarly enterprise, providing the information resources, books, journals, collections, and expertise that make research possible. Over time, the roles of research libraries have expanded and now encompass modern, mission-critical services such as research data management, curation, and sharing; systematic reviews; digital transformation initiatives; impact assessment; and an ever-growing range of functional and discipline-specific supports that connect directly to every stage of the research process.

These activities are now fundamental to how scholarship is created, published, and shared. Unlike the broad-based resources libraries provide to all users, regardless of discipline, project, or financial situation, this research support work is inherently more specialized and project-specific. Much of it happens within individual labs or through grant-funded initiatives, which means it requires deep expertise, significant staff time, and customized workflows tailored to each research team’s methodologies, timelines, and deliverables.

This project-specific nature of research support also intersects with how university research is funded. Research across a university exists along a broad spectrum of funding sources. Some research is supported by departmental or centralized institutional funds that are broadly available to the academic community. In contrast, other research relies on extramural grants, external funding from agencies, foundations, or other sponsors, which include specific compliance requirements, budget requirements, deliverables, and accountability tied to the projects or researchers.

Most libraries remain centrally funded through institutional budget allocations based on a historical indirect cost rate, often calculated based on the number of student and faculty FTE employees within an institution, even though recently developed services directly support sponsored research and/or the work is required by a sponsor and allowable as an award budget line item. As libraries more actively support sponsored research through specialized services and become more embedded in research workflows, some libraries and institutions are beginning to ask how best to sustain these services and make these essential contributions visible within institutional funding models that are facing uncertainty in federal research funding policy.

A Survey of Current Practice

To better understand this landscape, a recent exploratory survey examined how libraries are approaching and exploring award-based funding, sometimes referred to as direct charging, for services related to research support.

The survey asked libraries to indicate whether they were currently directly charging, considering charging, or not considering charging for a series of both general and specialized service categories. It also collected open-ended responses about perceived challenges, rationales, and institutional contexts.

Thirty-two institutions participated, evenly split between public and private universities, and roughly two-thirds represented medical or health sciences libraries.

General Services

The first set of survey questions focuses on general library services and infrastructure, or those broadly available across the institution, such as collections, preservation, and user training. Across these categories, the results are remarkably consistent: nearly 90% of institutions are not considering any form of direct charge.

| Category | Currently Charging | Considering | Not Considering |

| Content & Access | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 32 (100%) |

| Computational & Data Infrastructure | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 27 (84%) |

| Training & Capacity Building | 1 (3%) | 4 (13%) | 27 (84%) |

| Publishing & Dissemination | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 29 (91%) |

| Preservation & Archiving | 0 (0%) | 4 (13%) | 28 (88%) |

| Research Security & Risk Management | 0 (0%) | 1 (3%) | 31 (97%) |

| Visibility & Impact | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) | 28 (88%) |

| Other (General) | 2 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 30 (94%) |

Several respondents explicitly note that charging for collections, access, or training “would violate our mission and vision” or “undermine the library’s role as a shared campus investment.”

The few instances of current charging, primarily in medical libraries, are tied to computational or data infrastructure, often in collaboration with other campus technology units.

Specialized Services

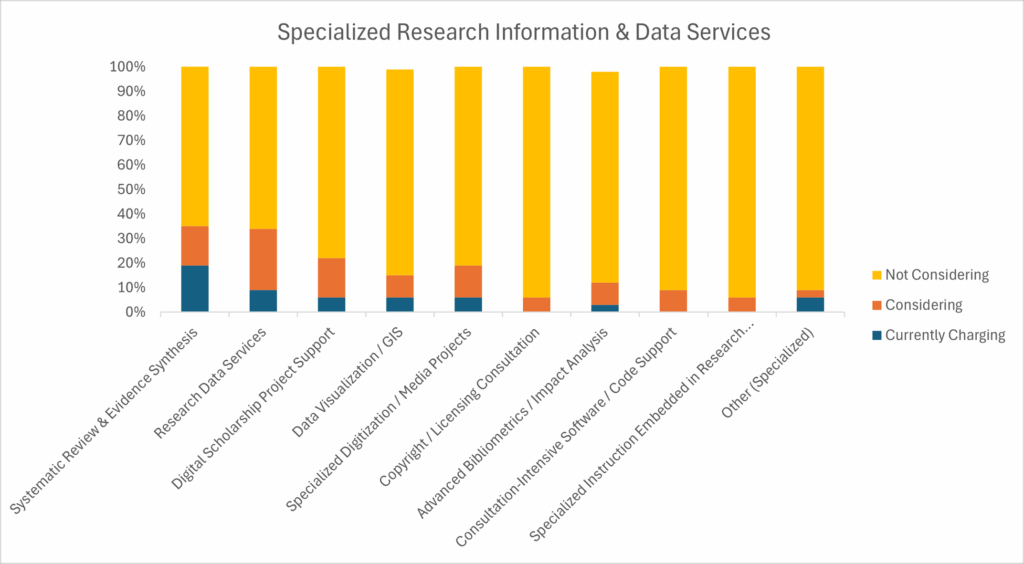

The second set of questions focuses on specialized, research-facing services that often require intensive staff involvement or infrastructure directly tied to sponsored projects. Here, the picture is more varied and exploratory.

| Category | Currently Charging | Considering | Not Considering |

| Systematic Review & Evidence Synthesis | 6 (19%) | 5 (16%) | 21 (66%) |

| Research Data Services | 3 (9%) | 8 (25%) | 21 (66%) |

| Digital Scholarship Project Support | 2 (6%) | 5 (16%) | 25 (78%) |

| Data Visualization / GIS | 2 (6%) | 3 (9%) | 27 (84%) |

| Specialized Digitization / Media Projects | 2 (6%) | 4 (13%) | 26 (81%) |

| Copyright / Licensing Consultation | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 30 (94%) |

| Advanced Bibliometrics / Impact Analysis | 1 (3%) | 3 (9%) | 28 (88%) |

| Consultation-Intensive Software / Code Support | 0 (0%) | 3 (9%) | 29 (91%) |

| Specialized Instruction Embedded in Research Projects | 0 (0%) | 2 (6%) | 30 (94%) |

| Other (Specialized) | 2 (6%) | 1 (3%) | 29 (91%) |

In total, about one in four libraries (25%) report that they are either currently charging or considering charging for at least one specialized service.

The strongest pattern emerges among medical and health sciences libraries, which report the highest incidence of current charging practices, particularly for systematic reviews and data curation.

One respondent explains that charging for systematic reviews “serves two purposes: it triages out projects that are not fully planned out and recoups the time cost to the limited number of librarians.”

Other specialized services, such as digital scholarship consulting, data visualization, and specialized digitization, are being explored by a small but growing number of institutions. These services often align more closely with the research lifecycle, making them natural candidates for pilot cost-recovery models.

Challenges and Tensions

Despite some experimentation, most libraries remain cautious. The challenges identified are consistent across institution types:

- Administrative burden: setting up compliant cost-recovery systems that align with federal rules.

- Cultural resistance: concern that charging would create inequity or reputational risk.

- Mission alignment: the sense that certain services should remain universally available.

- Blurred boundaries: uncertainty over where baseline service ends and specialized project-specific work begins.

Several respondents note that the real challenge lies in distinguishing baseline library services from project-specific work.

Institutional Differences

When analyzed by demographics:

- Medical and health libraries were the most likely to engage in or explore charging models, particularly systematic reviews, data management, and storage.

- Public universities cited compliance and administrative complexity as barriers.

- Private universities more often raised philosophical or mission-related concerns, such as maintaining equity across disciplines.

- Non-medical libraries were least likely to consider charging in any category, with many emphasizing that their services are intended for the campus as a whole.

A few respondents mention poster printing, event space rental, or visualization services as areas where direct charges already exist, often framed as cost recovery for materials rather than as fee-for-service models.

The Indirect Cost Recovery Context

The conversation about direct charging takes place against a backdrop of shifting assumptions about research funding infrastructure. While allocations for many libraries are not formally funded through their institutions’ indirect cost recovery (F&A), library budgets, however, are shaped by how institutions allocate the indirect costs recovered from sponsored grants. If federal definitions of allowable indirect costs evolve, or if reimbursement rates abruptly drop to the proposed 15% cap, while research costs continue to rise, institutions will need to re-examine how to sustain research support functions, such as library services.

The recent FAIR Model proposal from the Joint Associations Group (JAG) highlights this issue. The FAIR Model seeks to make many traditionally indirect activities, such as facilities, compliance, grants management, and Research Information and Data Services (RIDS), including journal and database subscriptions and repositories, visible as direct line-item award budget categories. The model effectively responds to calls for transparency of university research support costs as allowable direct costs, and includes many activities that libraries have and increasingly support.

The survey did not find evidence that libraries are proactively shifting toward direct charging to the funding source in response to these uncertainties, but many libraries acknowledged the need for better cost awareness. Several respondents emphasized that while they are not ready to charge, understanding and demonstrating the true costs of their services is becoming increasingly important.

Making Costs Visible

Across institutions, a shared motivation emerges: to better understand and communicate the true cost of research support. Libraries are beginning to examine the financial underpinnings of their work with greater precision, especially within institutions that are proactively seeking to recover their actual research costs. Moreover, as allocations for collections and personnel continue to be constrained and, at times, reduced, libraries need to align their investments more clearly with institutional priorities.

Several respondents describe early efforts to build internal cost models to estimate staff time, equipment, and infrastructure for services such as data curation, systematic reviews, and digital project consulting. Others note closer collaboration with research offices to clarify when and how library expertise might be written into grant budgets.

As libraries consider the implications and mechanics of direct charging grants for specialized services, they continue to absorb massive, centrally funded costs for public access – access mandated by funders. These costs are often invisible to individual researchers, PIs, and administrators. While these efforts are still early and exploratory, they signal a shift in perspective. The key questions now: How should libraries charge for services, and how can we make our contributions visible enough that researchers, administrators, and the entire research enterprise actually understand the value of what we deliver?

Looking Ahead

The survey offers a snapshot of a research library community in transition. While a few are moving decisively toward direct charging, many are monitoring the policy environment and considering how to make the financial aspects and operational costs of their work more transparent.

Libraries face a challenge balancing their commitment to providing equitable access for all users with the understanding that the research they support is funded by a variety of sources, some from institutional budget allocations and others from external grants with specific requirements and allowances.

Some libraries recovering costs from these funding sources, whether they are grants, sponsored projects, or allocations from the university or department budgets, could be developing a viable approach not only to sustain current services but also to expand capacity and support a broader range of researchers. This strategy might also help make the critical, often unseen work of libraries more visible to funders, administrators, and the research community, showcasing the valuable contributions that library expertise makes to successful scholarship and grant outcomes.

Direct charging is not yet a trend, but it is a bellwether. A handful of libraries are exploring and piloting, and many more are gathering information to inform future conversations about sustainability, policy, and advocacy. The preliminary efforts in direct charging reflect a growing awareness that libraries are striving to align their core services and values to the economic realities of supporting increasingly complex, resource-intensive research services.

Acknowledgments: Many thanks to Roger Schonfeld for serving as peer reviewer and Chef editor for this post.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Guest Post — Funding Research Services: How Libraries are Exploring Cost Recovery Models"

Thank you for these insights. I have question or curiosity – how does AI fit into this? Will the advanced AI tools be disruptive or supportive for these new cost recovery models for the libraries?