According to a recent analysis published on Oxford University Press’s OUP Blog, the population of librarians in the United States has fallen by 1/3 since 1990.

I tweeted a brief reference to this study when it was first brought to my attention, which generated some questions from onlookers: How is “librarian” defined? Are school librarians included in the population studied? Have some of the jobs remained the same but with different job titles?

Since large trends in the world of librarianship are likely to be of some interest to readers of the Scholarly Kitchen, I thought I’d see if I could find answers to some of these questions and also share other key findings from the study.

One fundamental thing to understand about the study is that it’s based on US census data (as organized by the Minnesota Population Center), which apparently means that the professional designation “librarian” is defined by the respondent. Given that the designation is self-defined, and given that the study clearly assumes that some “librarians” do not have undergraduate degrees (see the “Gender and Education Wage Difference Chart” for clear evidence of that assumption), it appears that wherever the study refers to librarians we might more accurately substitute the term “library workers.”

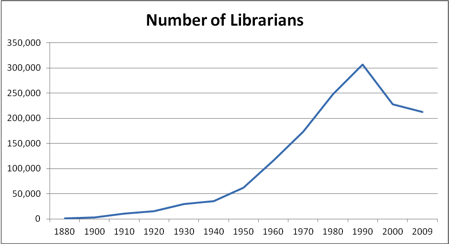

The “Number of Librarians” chart provided by the study’s authors shows a slow but steady increase in the number of U.S. library workers between 1880 and 1950, at which point the number began to climb sharply:

This makes intuitive sense, since the postwar period was marked by significant increases in government spending on education (and especially higher education) generally.

What is perhaps more interesting is the fact that this accelerated rate of growth continues right through the recessions of the 1970s and 1980s without any pause. The 1990s mark a sudden and sharp reversal, one which itself has continued without pause despite the fact that the 1990s were a boom period for the US economy (interestingly, the decline seems to have eased up a bit since 2000). Why the number of self-identified librarians continued to grow strongly through two recessions, only to begin falling sharply during a period of relative prosperity, is something of a puzzle.

Other interesting findings include:

- Contrary to the conventional wisdom, librarianship (or at least self-identified “librarianship”) has historically been a relatively well-paid profession, and continues to be: in 1940, median librarian wages were 153% of the national average, and in 2009 they were 137% of the average — though at various times between those two decades they have been much closer to the median wage of all workers. This is especially interesting given that the study clearly includes non-MLS library workers among the “librarian” population.

- The unemployment rate among library workers is relatively low – one-fifth the national unemployment rate in 2009.

- Library work remains a female-dominated profession, though the female-to-male ratio used to be very different and has fluctuated over the years. In the 1880s a majority (52%) of library workers were men, whereas in 2009, 83% were women.

- The study suggests that men and women in professional librarian positions have an almost identical median wage; however, among those without college degrees there is an even greater income gap between the genders than exists in other professions.

There are also some interesting data points about marriage rates, age, race, and the distribution of public and private settings for library workers over time. But it’s the general population trend that I find particularly striking. I’m trying to decide how worrisome I should believe it to be. Does the depopulation of our workforce signal an encroaching senescence of the profession itself? Does it suggest that the boundaries that separate library work from other kinds of information work are breaking down?

Given the counterintuitive patterns of growth during recession and decline during boom periods, it seems unlikely that the trend can be explained in terms of recent fiscal hardship.

One thing is certain: it will be very interesting to see what the trend line looks like after the next ten-year census.

Discussion

16 Thoughts on ""Librarians" — An Endangered Species?"

I think you’re right to assume “that wherever the study refers to librarians we might more accurately substitute the term ‘library workers'” at least for most of the data. What it looks like to me is increasing accuracy in the self-identification as a librarian since 1990. Perhaps improved awareness, education or form terminology occurred around then. Or perhaps the apparent trend of reducing numbers of paraprofessionals in libraries started at that time. Whatever the reason, the pattern of salary, education, gender balance, etc seems to match a decreasing number of non-librarians identifying themselves as librarians.

It would be comforting to think that the downward trend since 1990 is due to a sudden new accuracy in self-reporting, but I don’t see any reason to think that such is the case. What happened in 1990 to suddenly convince people who classified themselves as “librarians” in 1989 to stop doing so? And why has an _increasing_ number of such people made that correction in the years since?

I think your hypothesis that we’re seeing a decrease in the number of library paraprofessionals since 1990s has more face validity. It would be very interesting to see a truly rigorous library population study that makes more careful distinctions between different kinds of library workers. This one just brings home again the fact that to anyone outside the profession, anyone who works in a library is a “librarian.”

My personal experience is that law firms (I worked in one) and other non-academic businesses (e.g., the large aeronautics company my sister works for as a librarian) started to reduce or eliminate libraries and thus librarians around the time shown on the chart. And some prominent library schools closed then too, including Columbia and USC. Wonder if number would change if “information scientists” were included.

Let’s hope the trend reverses. Given the amount of information now available thanks to the Internet, we need librarians/information specialists more than ever to help students and info seekers wade through the gazillions of sites – some good, some bad – to get accurate and evidence-based information.

Since there is no way to distinguish between professionals and para-professionals in the census results, it is hard to substantial this, but my guess is that the trend line for professionals would show a much more gradual decline than that for para-professionals.

The birth of the internet and emergence of it as the primary means of distributing a significant portion of the content we deliver has eliminated a significant number of the jobs for “library workers” and replaced them with more technical positions that may or may not self-identify as “librarians” (regardless of the degree they may hold). E-journals don’t require check-in, don’t require shelving, don’t require monitors for serial rooms. High-density and robotic retrieval systems require fewer staff, etc…..

The elimination of much of the physical work done in libraries and the replacement of clerical-level bibliographic work with link-resolvers, shelf-ready services, etc… (much of which happened in the period showing the decline in the graph), is a likely cause for much of the decline.

If we overlay the demographic trend above with an aggregate of public funding for libraries nation-wide, I wonder what that would show? I also wonder how the erosion of this workforce maps to the state of the middle class?

What about information managers, knowhow managers, researchers, information officers, knowledge directors, etc etc. Some peoplr aren’t known as librarians any more

Or maybe the 1990s was when automation of the library occurred across most of the country! Computers replaced card catalogs-no one needed to maintain card catalogs anymore. Bar codes become standard eliminating the time consuming stamping and signing of index cards. And I am sure the technicians who design, program, and fix these devicess do not consider themselves librarians. These advances also made taking inventory easier. As the Internet advanced we could just look up information instead of having to go check out a book thereby reducing the number of librarians needed to check out and reshelf books. Not to mention that during the 90s spending on primary and secondary education decreased in many areas and school libraries had their hours cut dramatically. My Hs library was open during school hours (’93) but when my brother went four years latter, it was only open by teacher appointment! No more hanging out in the library during lunch for the bookworms! My MIL is a MLS and is a lecturer for an MLS program at a state university. There are still lots of people going for a MLS as her program has expanded so much that it is all taught online! Maybe next we’ll see a decrease in janitors because no one has to actually go and dirty up the school anymore.

As a public librarian (at least at this particular point in time 🙂 ), what I’ve been seeing is that as the boomers retire their positions aren’t being replaced. Instead, their duties are being shifted — some work being pushed downward onto paraprofessionals, and some divvied up among their peers. I can’t imagine this trend reversing, quite frankly, even once the funding picture improves. (Whenever that might be.)

Google Books data suggest that “librarian” peaked in the 1970’s: http://bit.ly/o2LR6W

I know a twenty-something who majored in internet marketing and is now in a MLS program to become a school/library/media educator. It could be the same program mentioned above — though she lives near the university, misses the in person real-time discussions that are not available in so many online classes. However they draw students from all over due to online courses and diminished availability of programs.

They feel that students and others, now more than ever, need proper guidance to access the best sources of information–to navigate the ever changing and widening information landscape. I have often wondered who will load each classes’ books onto devices every year–kids, teachers, or the library/info person.

I beg to differ on the prosperity of the 1990s. Early tomid–not so great.

Home values stagnating–folks taking losses on condos purchased a few years earlier. So many on unemployment and GHW Bush extended unemployment benefits and started taxing them–Read My Lips and all that. GHW Bush/Bill Clinton–The Economy Stupid–came out of the 1992 presidential election. Mid-late 1990s–many jobs were already outsourcing/freelancing/contracting, but within the US–more a matter of not paying benefits–insurance was then high but low enough to cover it.

In our state, MA, towns had to approve budget overrides to approve some of the funding beyond a certain % and many do not when times are tough.

My town never had a chance to build a new library in the early 2000s

due to the economy. Now with the changes in the info and book world, if we get the go ahead from the state, it will be built for a future we fear less than we did a few years ago. The library can move forward. It is a very active place for folks of all ages. Speakers, book events, concerts, computers, kids, teens.

I have a couple of card catalog drawers I picked up one summer in the mid-late 90s(?) when I stopped by a local university library seeking info. The Custodian was hacking up the card catalog so I grabbed a few drawers!

As academic libraries take over administrative responsibility for university presses, do the employees of the latter become librarians? Lines are blurring between publishing and what libraries do, so there might be some logic to this reclassification. That would help reverse the trend.

Interesting. I’m currently on sabbatical and writing away on Reinventing Academic Libraries for the Web” from the perspective of an established virtual library at an online university. For a little more statistical nuance, check out Davis, Denise, Trends in Academic Libraries, 1998-2008. Chicago. American Library Association, 2011