Back in the day, when demand-driven acquisitions (DDA) was still called patron-driven acquisitions (PDA), I worked on a project to determine how DDA would affect the university press community. I reported on that project in The Scholarly Kitchen and included a link to the full report. DDA, in my view, was going to pose some significant challenges to book publishers: it would delay some purchases (creating a cashflow problem), it would reduce the income from some books (by substituting short-term rentals for outright purchases), and it would result in the loss of many sales (for those books that appeared in the DDA part of a library’s collection, but never elicited any demand that would generate income).

Listening to the rumblings in university press circles, I have to assume that all this, the dystopian library situation, has come to pass. Many presses report that sales are down; some presses are considering withdrawing from DDA programs to stem the loss. It seems to me, though, that DDA is here to stay: withdrawing from these programs may simply mean that librarians may not buy many press books at all. A better question, I think, is how to work with the DDA situation to figure out how its obvious liabilities to publishers can be offset.

Before I go any further, let’s stipulate that whatever harm DDA is doing to publishers, librarians are not to blame. It is difficult for many publishers to understand this, but libraries do not exist for the benefit of publishers. When a library introduces a DDA system, it is not being done to impact publishers’ margins; it is being implemented to lower the costs of a library–and, not incidentally, to align the collections and purchases for those collections with the living research activity on campus. For all the invocations of “the academic community,” publishers and librarians play a zero-sum game. Librarians buy, publishers sell: no buyer ever wanted a price to be higher, no seller ever wanted a price to be lower. DDA may be hurting publishers precisely because librarians are doing their job.

Publishers have to do their job, too, of course, and that includes ensuring the financial well-being of their organizations. If DDA puts pressure on sales and margin, what can a publisher do to increase them?

We should begin with pricing. American university presses simply don’t charge enough for their books, something that becomes apparent when the prices of American presses are compared to their peers overseas. With DDA the invitation to increase prices is extended to all books that can support it. That means books that are carefully researched and impeccably edited: for such services publishers should not be shy about charging what a book is worth. We do not yet know how long DDA delays the use and subsequent rental or purchase of a book (since there has to be actual demand before any money changes hands), though ProQuest, with the leading DDA services, may now be in a position to make a data-grounded guess. But ProQuest is not likely to share that information with the publishers it works with in a form that would be useful for revising marketing programs, so publishers will have to develop this information on their own. At some point we will come to understand that the book that formerly would have been priced at $30 should now be priced at $40, and the book that was formerly $40 should now be $50. Publishers should be inching up their prices in the meantime.

A serious problem for some DDA services is that they allow for too much sampling. In some instances a user can view as much as 10% of a book before any kind of transaction takes place. Whoever came up with the 10% figure, I do not know, but it clearly does not work for scholarly books (it could work for a novel). A 400-page book on Czech history or the politics of the ancient Parthians or John Milton’s prosody may rarely be read from beginning to end by many people; readers are more likely to dip in here and there, perhaps reading one or two chapters: a scholarly monograph, in other words, very often displays properties we associate with reference books. The 10% sample for such a book comes to 40 pages, which likely represents the amount viewed by a substantial portion of the work’s total readership. A figure closer to 5 pages makes far more sense–the material is intended as a sample, after all, not as a substitute for reading and purchasing the book.

DDA could come to benefit publishers over time–and benefit libraries as well–if there were changes in certain library practices, but these changes are not yet on the horizon. A case in point is inter-library loan. ILL is very expensive for libraries, as they have to ship print books back and forth. A less costly (and faster) solution for libraries would be short-term rentals via DDA, which has the advantage (from a publisher’s point of view) of providing some revenue back to the publisher. Indeed, many publishers signed onto DDA programs with the expectation that ILL would eventually fade away. For a number of reasons ILL is not going away anytime soon, not the least being that not all books are available in DDA programs and some users of ILL prefer to work with print. On top of this is inertia and the understandable reluctance to redeploy or dismiss redundant staff. So now we have DDA programs, which shrink publishers’ revenues, living side-by-side with ILL, which increases libraries’ costs.

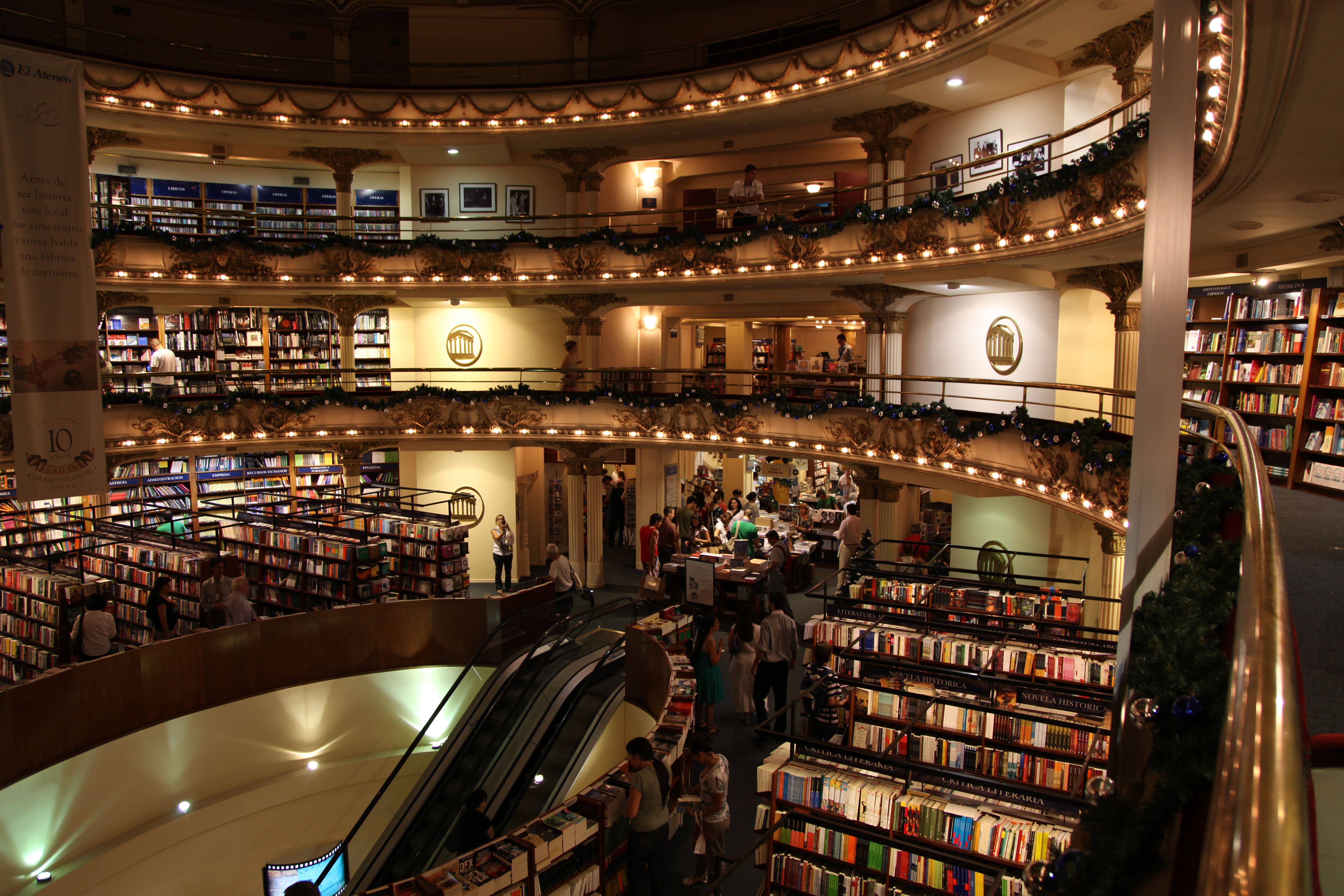

An even bigger win for libraries and publishers alike would be to extend DDA into a bookstore within the library catalogue, an idea which makes some librarians apoplectic. Without for a moment minimizing the challenges to get such a system to work, a service of this kind would provide revenue for publishers, referral fees to libraries, and broader access to more titles for library patrons. Here is how this would work:

Scenario #1: A library patron performs a search on the library catalogue. The search reveals a book that is appropriate for a particular research project; that book is already in the library’s collection. The book (whether in print or electronic form) is thus available to the patron–for print, by going to the library to pick it up; for an ebook, by clicking on the link.

Scenario #2: the patron searches for a book and discovers a record of what appears to be a useful book. The patron does not know that the library does not own the book; it is part of the DDA offering. The patron requests the book and the library is charged for it by the DDA vendor.

Scenario #3: the patron searches for a book and discovers a record of interest. But the record indicates that the book is not in the library’s collection. The patron is given the opportunity to purchase the book on his or her own account. The book is then delivered to the patron, whether in print or electronic form. The patron’s credit card is charged. The publisher and vendor are compensated for the sale, and the library receives a sales commission on the transaction.

DDA is something we are all familiar with, but don’t recognize it as such. It’s called a bookstore. All consumer sales are demand-driven. Institutional markets are different, however, in that librarians typically select books on behalf of their community. DDA in the library can benefit from insights gained in bookstores and can combine these insights with the curatorial skills of an information professional.

I anticipate that DDA is going to look somewhat different two years from now. Even as more and more libraries initiate or expand DDA programs, many publishers will consider scaling back their support or negotiate for better terms. If librarians want publishers to accommodate them, they may wish to take a hard look at their ILL operations and think about becoming a micro-Jeff Bezos on campus.

Discussion

42 Thoughts on "Revisiting Demand-driven Acquisitions"

Great post, Joe. But I would add one other element, besides fixing the obviously broken purchase triggers, to a publisher-worthy DDA program: Subscriptions.

One of the advantages to running an internship program at a university press is that I talk to students about how they do their course work almost every day—they’re something of a captive focus group—and what I hear over and over is that they do not read scholarly books like they read fiction. It is never linear. Instead they find what they need, get the citation, and then get out, so even a 5 page trigger wouldn’t capture a fair amount of revenue for what is clearly an instance of use, and exactly the kind of use librarians want to provide. DDA is a system where publishers are providing that kind of use for free, and I think that’s probably the kind of use that constitutes the majority of how our books are used in libraries. Frankly, we simply can not afford to be that charitable. If instead of only use triggers providing revenue, subscriptions also provided revenue, then we could more sustainably support the important risk taking that publishers must and should do. Subscriptions would allow university press publishers to publish in less popular but important areas that wouldn’t see a huge amount of sales revenue. It would support a more communal publishing environment instead of the winner-take-all, ruthlessly capitalistic popularity contest that DDA is currently imposing. By spreading the revenue over a collection rather than funneling it to only the most popular work, the devastating impact that DDA has on scholarship writ large, and the scholars university presses publish, can be mitigated. It’s not just about the money.

While I agree that libraries don’t exist to solely support university presses, they do exist to support their faculty, and that includes their publishing faculty. I would hope that libraries would keep that in mind when choosing a DDA model. Choosing one that creates a sustainable environment for their faculty is as important as their policies to create a more sustainable world.

Also, YES YES YES TO BUY BUTTONS IN THE CATALOG! Don’t send your faculty to Amazon when you can provide the same service your community bookstore once did, and can generate revenue to help pay for that subscription I just proposed. Bookstores used to be incredibly discovery engines for both faculty and students, and with their closing we’ve outsourced that same discovery to tech giants with very different priorities than we have. Buy adding a subscription layer, and a purchase layer, we can expand library catalogs exponentially, sustainably, and inclusively. More books and more access at lower transaction costs. Libraries, faculty, and university presses shouldn’t just be rational actors merely responding to market forces. We need to work together to create better discovery and revenue/spending models that sustainably consider the larger scholarly production environment. Buy buttons and subscriptions could go a long way to accomplishing that on our campuses.

So, speaking of subscriptions, how does DDA interact with existing subscription services for ebooks like JSTOR and UPCC?

While I agree that libraries don’t exist to solely support university presses, they do exist to support their faculty, and that includes their publishing faculty.

This is obviously true. However, the library’s role in supporting our “publishing faculty” is limited. The library supports them primarily by giving them access to resources they need in order to carry out their scholarly work. Not everything that can reasonably be characterized as “support” is within the library’s purview. We don’t support them by paying their research assistants, or by giving them research grants out of our operating budgets, or by upgrading their computer software. Nor do we support them by buying the books that they write. We may, in fact, buy the books that they write, but we do so if and when those books fit our particular libraries’ mission. (There are some academic libraries that make it a point to buy all publications of their institutional faculty, but when they do so the goal is not typically to put royalties in faculty pockets or to prop up faculty’s book sales; it’s usually to ensure that the library collection contains a representation of institutional output. In such cases, the circulating collection is acting something like an institutional repository.)

Understood. But if you were doing something that you knew was actually hurting a faculty member’s career, would that make a difference? Something that was actually contributing to the decline of their discipline because their particular field of study wasn’t popular, should that be a purchasing policy factor?

But if you were doing something that you knew was actually hurting a faculty member’s career, would that make a difference?

You mean, when did I stop beating my wife? 🙂

That’s a pretty tendentious question, but the obvious and unavoidable answer to it is yes. You could just as well ask it in the context of journal cancellation decisions, collection weeding, personnel cuts, and any number of other difficult decisions that are made necessary by resource limitations. We will inevitably have to make decisions that could (or absolutely do) hurt faculty when we don’t have resources sufficient to do everything possible to help every faculty member. If we had infinite budgets and infinite space, we would buy everything there is to buy. But we have neither, so we have no choice but to make decisions that hurt–just as you do when you opt not to publish a manuscript, even though its author is a scholar who needs to get published.

As for this question:

Something that was actually contributing to the decline of their discipline because their particular field of study wasn’t popular, should that be a purchasing policy factor?

By the logic of this question, the library’s failure to buy everything ever published constitutes a contribution to the decline of some discipline or other. Well, maybe so. But that’s life when your budget, space, and mission are limited.

OUP is already doing subscriptions for their ebooks. I don’t think it’s the solution (at least not for my library) but maybe someone from OUP could chime in here on how there subscription program is fairing?

What OUP is doing is a subscription alone. I’m suggesting a subscription/DDA model hybrid that provides limited access through a subscription—maybe two pages after clicking from the search results—and still offers DDA for collection development if more access is required. And to keep the prices of both the subscription and purchase low, buy buttons would be implemented to provide additional revenue for both the library and the publisher. If a library chose not to include the buy buttons, the price of just the limited access subscription and the permanent purchase would be higher.

On ILL there is a program the CCC offers called Get It Now that has been very effective, but so far it only includes journal articles, not book chapters. One reason is that, to operate effectively in a Get It Now system, book chapters would need to be assigned DOIs, and very few are now.

Does DDA result in more buying of revised dissertations than regular approval plans do? We still need a study to determine whether approval plans have resulted in fewer revised dissertations being purchased (as a study I did for Penn State Press indicated for one field, Latin American studies), and with that study in hand, we could do a similar study of purchasing of revised dissertations through DDA for comparison.

On book pricing, American presses have not followed the European model, which priced books for the library market only, because US presses aspired to have their books affordable to individual purchasers. The goal has been to maximize the number of copies distributed, not the income received, and that is a major difference in the interpretation of their missions by US and European presses, It is also the reason that US presses have been much more interested in issuing their books in cheaper paperback form than European presses have. Joe’s encouragement to raise prices does not take this difference into account.

When a library introduces a DDA system, it is not being done to impact publishers’ margins; it is being implemented to lower the costs of a library–and, not incidentally, to align the collections and purchases for those collections with the living research activity on campus.

This is one of the very few areas where you and I disagree about DDA, Joe. From my perspective as a librarian, I would reverse what you say in the sentence above: for me, the primary purpose of DDA is to align our library’s purchasing behavior with the scholarly activity on campus. Lowering costs is secondary, even incidental. In fact, I’d go further than that: lowering costs is not really a consideration for me at all in implementing DDA–I have no desire to spend less money on books. I want to spend just as much money on books as I ever did; I just want to ensure that every dollar I spend actually helps a student or researcher.

“I have no desire to spend less money on books. I want to spend just as much money on books as I ever did; I just want to ensure that every dollar I spend actually helps a student or researcher.”

Yes!! This is what drives me crazy about this conversation – the idea that PDA/DDA saves money. I manage our large PDA/DDA program at my university and we struggle to keep up with the costs. We’re not spending less money by having the program, we’re spending the same amount more usefully (hopefully). The budget is what it is. Any money “saved” by not purchasing an e-book because it did not reach the trigger point is spent on a different one.

None of the PDA models for which we’ve signed agreements allow for anything like 10% of the book to be viewed without payment (unless it’s a very short book!). The key events are time spent browsing, number of pages viewed, and downloading/printing any content.

JSTOR allows up to six chapters to be viewed before a purchase is triggered.

http://about.jstor.org/content/books-jstor-demand-driven-acquisition

That can be significantly more than 10%.

We wouldn’t have signed on for such a deal!

These models vary greatly from vendor to vendor. In one case of which I’m aware, the first two uses (of whatever length and substantiality) of an ebook generate no charge; the third use triggers a purchase. Under another model, the first use (again, of whatever length or substantiality) generates a charge of 10% of list price; so does the second. The third triggers a permanent purchase at full list price.

Although we sometimes hear calls for standardization of models, my guess is that they will continue to vary from vendor to vendor, since each model represents a different value proposition. Having different access/purchase models allows vendors to differentiate from each other even if they’re offering access to a similar corpus of books–in kind of the same way that brick-and-mortar bookstores may be selling much the same stock, but compete with each other by offering different services (or simply better service).

And publishers need to decide which of these models we are comfortable participating in.

Oh, auto-triggering purchases of e-books, especially when the user (patron) doesn’t realize their use is costing the library money (by silently triggering a purchase)? I’m not sure I like this at all… especially when the ebook GUIs are often so difficult to use. If I’m reading electronically, I want downloadable PDFs, and to not be trapped to a hard-to-look-at or hard to use GUI (e.g. that of UC Press). But, the question of what eBooks should look like and how they should work is a separate matter – to focus on DDA, I think I’d much prefer to have my library simply buy hard copies.

This issue doesn’t seem very different to me than that faced by the newspaper industry and their use of paywalls. The main difference is that the third-party companies supplying newspaper publishers their paywalls are willing to share information about usage across their clients and allowing each paper to fine-tune the paywall to however many free views a publisher wants to offer.

It is hard to believe that the DDA suppliers don’t have the data to evaluate how much should be given away for free to optimize usage and revenue/profit.

Publishers should also consider integrating opportunities (incentives) for readers to identify themselves to the publisher. This can create a win-win: the reader gets something of extra value and the publisher identifies the ultimate consumer and drives additional demand.

Very interesting. Thanks for sharing with us about this. Two thoughts/questions come to mind.

(1) I find it interesting that you say publishers need to be charging more for their books. I was actually just talking with one of my fellow grad students about how some publishers charge too much. I wonder what you think about the following example:

Tuttle’s “Japanese Woodblock Prints” by Andreas Marks, for example, has a cover price of US$30 for a large, hardcover, 300+ page book with full-color illustrations on nearly every page, a very reasonable price for a book I’d expect to normally be $40-50. I can only imagine how many copies they’ve managed to sell to individuals, through Amazon, brick and mortar bookstores, etc.

Meanwhile, Brill’s “Publishers of Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Compendium,” by the same author, admittedly nearly double the length but otherwise a very equivalent publication, in fact duplicating much of the same content, is going for a whopping 147 euros. I can’t imagine they’ve sold very many copies at all beyond libraries and the like.

So, are you saying that Brill is doing it right? Or should both books be more in the $40-60 range? I ask not to be passive aggressive or snarky, but genuinely, I am curious as to your expert opinion on this, to expand on what you were saying about publishers’ prices.

(2) On a separate subject, speaking of patron driven acquisitions, I wonder what you think about the following two scenarios, with which I am much more familiar. How well do these do for libraries? Do they work well? Are they advisable? Are they too expensive?

Scenario 4: the patron searches for a book and discovers a record of interest. But the record indicates that the book is not in the library’s collection. The patron is given the opportunity to have the library purchase the book for him. The book is then delivered to the patron, in print form (as a book now in the library’s collection, with the requisite limited borrowing period, etc.), and the library is charged.

Scenario 5: the patron searches for a book and discovers a record of interest. But the record indicates that the book is not in the library’s collection. The patron requests the book via ILL. The library notices this is the Nth time someone has requested the book from ILL, and so the library goes and buys a copy to add to their collection.

I’m not a librarian or library sciences student, so I don’t know much about the inner workings and financial considerations of library operations – which is part of why I so enjoy reading the Scholarly Kitchen – but as a patron, I quite like either of these Scenarios, especially when the system somehow allows the book to be acquired quite quickly, and not after the many months (sometimes up to a year or more) it often takes when simply requesting a book through the library website’s “Recommend a Book to Buy” form, or by speaking directly with a librarian.

From my layman’s point of view, it would seem either of these scenarios would be pretty good – it allows the library to purchase those books it knows people want, thus catering to the actual research going on on campus (in my case, this means buying many more books on Okinawa than a China/Japan/Korea/Taiwan section would normally think to carry), and it saves them from the costs of having patrons keep requesting the same book on ILL because it’s not in the collection. So, what do you think? Are libraries moving towards or away from systems like these? Thanks!!

Scenario 5 already happens on an informal basis. We review book ILL orders each month to keep an eye out for popular titles we might want to buy. Scenario 4 is a bit dicier. PDA is fine on a limited basis but there are concerns that prevent it totally taking over selection duties. For one, just because a subject is more popular doesn’t necessarily mean one should scant other areas in favor of it. Books about Freud and Jung are the most popular psychology books we circulate but I don’t purchase new content on them because they aren’t relevant to current psychology research. That’s an extreme example but one can see the principle behind it. PDA is valuable though in general, especially as a window into patron interests.

Interesting point about Tuttle. I think in this case they benefit from focusing exclusively on one subject area. I’ve seen Tuttle books for sale at brick and mortar stores that do not primarily sell books. They only have one niche market, but they know it very well, and I would guess that they are well known in it too. That’s marketing, word of mouth, distribution and discoverability right there. I think Joe has mentioned specializing as a possible strategy for university presses before.

It’s quite simple to me: publishers can make their offerings as expensive and restricting as they want, but the total amount of $€$€ available for book acquisition will not increase (rather decrease), and within that amount publishers with the best prices and least restrictions will get the best share of the market. Those that raise prices or impose more restrictions will find that fewer of their books will be bought and that their offerings will be removed from PDA/DDA selections made by libraries (which already happens). Do not count to much on the idea that your catalogue/book titles are a monopoly and will be bought whatever the price and conditions. It’s up to you….

It’s quite simple to me: publishers can make their offerings as expensive and restricting as they want, but the total amount of $€$€ available for book acquisition will not increase (rather decrease), and within that amount publishers with the best prices and least restrictions will get the best share of the market.

This would be true if book-buyers (including libraries) were making purchase decisions based on price and DRM alone. But no one, in fact, buys books that way. If we did, everyone would simply fill up their virtual shelves with free ebooks (of which thousands are offered every day) and their physical shelves with nickel paperbacks from the local charity shop. The variables you’re ignoring are relevance and quality, both of which are of great importance both to individual and institutional buyers.

Dear Joe,

A really good essay.

It seems to me that DDA is not a template that encompasses the way that scientific researchers work. I’ll give you an example: a theoretical physicist works on a problem in 1964; in July 2012 (48 years later) the experimental physicists announce the discovery of the Higgs boson (Higgs mechanism) at CERN. When the original theoretical thinking was being accomplished (the Higgs Six) even world famous physicists (Nobel laureates) thought that this highly difficult problem “was a waste of time.” Now the experimental confirmation is considered one of the most important scientific discoveries in this century. Only fair to ask: how does the DDA template match-up with the magnificent experimental results announced at CERN?

John Long

I don’t think DDA has anything to do with CERN. I am puzzled as to why you think there could be a connection. DDA is exclusively for books. The kind of research you describe is usually published in journals.

Hi Joe,

Yes that’s true, much of the research is accomplished via serials literature, but scholarly monographs are important as well. The point I neglected to make is that scientific research has little to do with popularity, and the DDA template has everything to do with popularity. So, the DDA template is a significant much needed tool, but it can completely miss salient developments in research (my example, Higgs boson). Another example: in the early days in the field of chaos dynamical systems (fractal geometry) research one of the leading mathematical researchers was told by more senior mathematicians that he was wasting his time. Since then scientists from many disciplines have found ways to use chaos dynamical systems in their own fields (geology, physiology, medicine, finance, biology, environmental sciences, computer science (Benoit Mandelbrot), and beyond science in Hollywood films). Much of the early work in this field developed from monographs in mathematics (going back to Gaston Julia).

Thanks,

John Long

I am neither an advocate nor opponent of DDA. I was simply describing the implications of how it works. Many librarians are keen on using it, and it does not seem to be going away. You may wish to raise your points to librarians. Most publishers are cooperating with DDA because they have to.

I don’t think DDA is unique in possibly missing salient developments in research. The alternative to DDA is that a librarian selects material to acquire manually or, more likely, relies on a vendor to do pre-selection according to specified criteria. In either case, a human might end up excluding something that seems unpopular.

In other words, the switch from traditional acquisition mechanisms to DDA isn’t about a switch from buying nearly everything to buying only popular things; it’s a switch from buying a limited set of things that a librarian thinks people will want to use to buying those things that people actually want to use.

Only the largest research libraries can afford to collect material “just in case”, and they will continue to do so, even in the era of DDA at other institutions.

When thinking about DDA, it’s very important to understand how it really works in research libraries. It really doesn’t reward “popularity”–what it rewards is local relevance. For one thing, the population of books made available via DDA mechanisms is always shaped by some kind of profile, and in academic libraries these profiles generally focus on scholarly and professional books and exclude popular ones (though I’m sure there are some exceptions to this rule). Second, while the usage triggers that cause a purchase do vary somewhat from platform to platform, they are always sensitive enough to trigger a purchase when the book in question is used by a tiny minority of users–very often, in fact, usage by a single person will trigger the purchase. What this means is that DDA serves small numbers of readers in highly specialized disciplines just as well as it serves the hundreds of students in a survey class. So the idea that “the DDA template has everything to do with popularity” has, itself, more to do with common misunderstandings about DDA than it does with reality.

This does not reflect the my experience. From a publisher’s perspective, DDA is amplifying popularity. I’m curious how a library knows which titles are popular and which are not when they don’t have a full list to compare purchases against. They might know the titles they buy, but that’s a single purchase. How do they know how many copies are sold across a publisher’s list, and how many titles are orphaned, never seeing a sale?

Tony, can you explain what you mean by “amplifying popularity,” and share the data on which you base your understanding of what’s happening?

As for the rest of your comment, I have to confess that I’m not sure exactly what you’re asking. A library that runs a DDA program has no way of of knowing what is and isn’t popular in the broader marketplace, and isn’t particularly interested in knowing. What we’re trying to do is provide access to books that will further the scholarly work of those we’re charged with serving. We limit the universe of books available for DDA because our limited resources require it, and we limit them generally to scholarly books because our mission is to support scholars. From that point forward, purchases are driven (or not) by our success (or failure) in providing access to those books that are useful and relevant to our scholars. Whether those books are “popular” or not in the larger marketplace is both unknown and irrelevant to us. In other words, books selected via DDA may or may not be popular, but the DDA program itself is pretty much agnostic about popularity. What it rewards, directly, is not popularity but relevance to the audience served by the library.

Tony, the DDA services layer an approval plan on top of the titles in the service. This is exactly what libraries have done for years. If a book is not in the approval filter, it doesn’t go into the DDA service. What DDA does (which is not good for publishers) is to delay or eliminate purchases or rentals if there is no actual demand for the title at that institution. There is no more a popularity contest thatn there is with approval plans set up at YBP.

What DDA does (which is not good for publishers) is to delay or eliminate purchases or rentals if there is no actual demand for the title at that institution.

That is true only if we assume DDA triggers are accurately measuring usage. When up to six chapters can be used before a purchase is triggered I don’t think we are accurately measuring usage. We shouldn’t conflate demand with usage when five chapters, or even ten percent of a book can be used for free.

My data isn’t the most useful to measure the full impact of DDA because we only participated in a few DDA programs experimentally and have since exited all of them upon discovering the number of libraries that stopped ordering via straight approval and switched to DDA. Even our experimental dabbling in DDA caused a significant drop in our sales through YBP, but only in disciplines where e-books were available. In art history where our ability to release ebooks is limited by third-party permissions issues and where scholars prefer or need print, we saw no drop and in fact saw a slight increase in revenue, but in every other discipline which did participated in DDA there was an overall drop of around 15% to libraries that chose DDA over straight approval. Books that would have had strong sales before DDA continued to sell well and many sold better (often those were titles that might have generated text adoption sales), but titles with smaller audiences sold almost nothing. And since neither my director nor our editor-in-chief would appreciate me sharing the titles of books that we felt had disappointing sales (not to mention the authors of those books) and I don’t know how I could provide credible data without sharing title sales, I would instead strongly encourage both of you to talk to Mike Zeoli at YBP about the impact DDA/STL is having on the whole university press market. His data is not mine to share. I can tell you that we have drastically changed our acquiring in romance language studies (moving to books with strong adoption potential) and have entirely left the field of continental philosophy because those fields are no longer sustainable except for sure bets. Do you think those are no longer worthy fields of study, or might it be that they are too esoteric to survive in an environment where they will no longer generate approval sales and instead must ruthlessly compete in DDA programs?

I totally get why libraries find evidence-based acquiring attractive, especially in this economic environment, but we need a much better yardstick to measure with, and we need to modify those models to be more inclusive of the minor disciplines and subfields. None of the current models support the minority disciplines and instead reward only sure things. And it really pains me to hear librarians entirely dismiss the idea that they have any role to play in the larger scholarly production environment beyond just cutting a check when so-called usage occurs. Many of those same libraries are creating under-used publishing platforms and repositories with the money they used to spend on acquisitions. I’d love to see those platforms forced to prove their merit through usage or suffer the same fate that books and disciplines are subjected to in DDA programs. My proposal to modify DDA programs with subscriptions sincerely attempts to address what is now a ghettoizing model that will never support the full range of scholarly production that our faculty/authors are engaged in.

I can tell you that we have drastically changed our acquiring in romance language studies (moving to books with strong adoption potential) and have entirely left the field of continental philosophy because those fields are no longer sustainable except for sure bets. Do you think those are no longer worthy fields of study, or might it be that they are too esoteric to survive in an environment where they will no longer generate approval sales and instead must ruthlessly compete in DDA programs?

Are they worthy fields of study? Of course they are. But can you tell me what field of study, however narrow or esoteric, would be “unworthy”? When it comes to book publishing, the “worthiness” of disciplines is really not at issue. The question is whether a monograph on a given topic will have a readership sufficient to justify the cost of publishing it. If it doesn’t, then asking libraries to buy it anyway, so that it can sit unread on our shelves, hardly seems reasonable–even if by doing so we can be said to be propping up a “worthy field of study.” Every decision to purchase one book is, necessarily, a decision not to purchase another one; this means that there is no purchasing decision that can’t be construed as the failure to support a worthy field of study.

I totally get why libraries find evidence-based acquiring attractive, especially in this economic environment…

Once again, I have to emphasize that libraries are not (in any case that I know of) implementing DDA programs because we expect them to save us money. On the contrary, most of us got into DDA despite serious fiscal trepidation–the warning voices were all about how DDA was going to blow out our budgets. Whlle those fears turned out to be exaggerated, I’m not aware of any library that is spending less money on books because of DDA. What we are doing is spending a much higher percentage of our book budgets on books that actually help our students and researchers do their scholarly work.

I’m curious how DDA affects less popular fields of study (popularity being measured by the number of undergraduate majors in the fields). Wouldn’t there likely be more “hits” on books in fields like American history, generating purchases, than in fields like, say, linguistics or archaeology–assuming your university even offers these more esoteric majors. Sales in these fields would be lower in general on the traditional model, on the whole, for the same reason, but I’m wondering if approval plans would still generate more orders for books in these fields than DDA would.

I am a librarian who works in collection development, and I have seen our list of titles accessed through DDA. Several factors are at work here. For one, different disciplines use e-books in different ways. History, literary studies, art, and other humanities topics are not accessed very much in e-book format, as these researchers tend to prefer print. Due to the long shelf life of humanities topics, our print collection tends to support these folks quite well. Additionally, research has shown that many e-book platforms are sub-par, with onerous DRM restrictions. Readers of long-form monographs, such as humanities researchers, are particularly apt to avoid e-books due to eye strain, as well. On the other hand, DDA is more popular in the fields of business, education, the sciences, and social work. The electronic journal access model of finding bite-size chunks of articles/chapters has revolutionized the way that research is conducted in these fields. Many scientists almost totally avoid monographs altogether, focusing instead on the journal literature.

One interesting thing we found is that there were a bunch of uses of books on cinema studies and on computer science. My theory is that people who are more web-savvy, such as those involved in computer science and digital media, might be more prone to use e-books. So if DDA were to become the library’s keystone of collection development, you would have users’ tech skills and aptitude for e-book research determining your overall collection development strategy. That is kind of problematic.

Another thing to consider is that a “use” needs to be dug into to explore its true relevance. A “use” of a chapter for five minutes is not indicative of much learning going on. That to me is indicative of someone getting fed up with a poor user interface. A “use” of a book by a questionable publisher, or on a faddish topic, might not be as “relevant” as less popular instances of medical or scientific information being accessed. So, determinations of quality are still relevant, and librarians should still exert some quality control over what information is being released to patrons.

A final word on the issue of DDA profiles. While it is true that DDA profiles can be tailored to exclude, for example, outmoded subjects like phrenology, psychoanalysis, etc., keep in mind as well that DDA profiles don’t get you to a really fine-grained level of detail.

Having said all of that, I still very much support DDA on a limited, experimental scale, as a way to analyze usage patterns, and purchase content. A DDA project can be extended to a higher dollar total, depending on the librarian’s comfort with it as a purchasing model.

From my perspective as a librarian, a much bigger problem related to e-books exists, and that is that the e-book vendor market for academic libraries is in complete disarray. Many products are not optimal for usability, especially on mobile devices, which I think are the wave of the future when it comes to e-books. Prices are high, and subscriptions fail to address concerns of future preservation. I do not feel comfortable turning our library’s future over to the hands of Ebrary. When it comes to e-books, libraries are subject to the whim of private companies in a way that was not nearly as important when print was the default preference. These are the problems that keep me up at night. DDA just feels like a cool experiment we are doing.

I am afraid that the 2 to 8-fold increase on the cost short term loans imposed by many big publishers over the last 5 months will effectively kill PDA/DDA: http://www.eblib.com/pdfs/PublisherStlChanges-JuneJulyAugSept2014.pdf

No library can sustain paying 25-40% of the hardback price for just one patron reading a chapter in a book for one day. Libraries can buy a paperback edition for the same or less and have patrons lend that book for years and years to come.

Jeroen, if that is your argument for not doing some level of DDA, how do you then justify paying full price for a book that is never used and sits on your shelf year after year taking up valuable space?

It does seem to me that DDA, when integrated with a library’s approval plan (which weeds out inappropriate titles for the institution), is here to stay. The question is getting the economics right. The current practices have the economics wrong, but things change and parties adjust. Patience, everybody. Let’s give us all some time to learn.

I think one principal effect of DDA will be to undermine the business approach that many university presses had adopted once they discovered, circa 2000, that many libraries were buying paperback editions if they were published simultaneously. In reaction many publishers, as we did at Penn State, stopped doing simultaneous editions and instead started issuing the hardback edition first in a small printrun (usually under 400 copies), hoping that it would sell out within 12-18 months so that the paperback could then be issued via SRPD or POD. The advent of DDA has affected that strategy critically by lengthening the process of sell-through of the hardback edition, which was greatly aided by approval plans, so that paperbacks may now take much longer to issue, if they will be issued at all. If the books are sold in the DDA plans as ebooks, of course the market for a paperback edition is pretty much eliminated anyway. The loss of that market is not likely to be compensated by the revenues brought in through DDA.