Continuing an annual tradition, we take a moment to pause at year’s end to look back on the best books we encountered. As always, this is not a “best books of 2015″ list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2015 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new. This is one of the great things about books in all forms — they endure, invite visitation and revisitation, and beckon with ideas. Here’s Part 1 of our list, Part 2 is here.

Joe Esposito: Let’s hear it for garage sales. My wife stumbled on a used paperback of Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, predicting, correctly, that I would love it. Never mind that she would not read a book of this genre for her life. It’s a great book, and an award-winner. But in fact it is not science fiction but a book that uses the trappings of science fiction in a post-modern manner to probe the pained personal relationship between a boy and his father. I found the book to be funny, moving, clever, and endlessly inventive. Yes, go out and read it.

Joe Esposito: Let’s hear it for garage sales. My wife stumbled on a used paperback of Charles Yu’s How to Live Safely in a Science Fictional Universe, predicting, correctly, that I would love it. Never mind that she would not read a book of this genre for her life. It’s a great book, and an award-winner. But in fact it is not science fiction but a book that uses the trappings of science fiction in a post-modern manner to probe the pained personal relationship between a boy and his father. I found the book to be funny, moving, clever, and endlessly inventive. Yes, go out and read it.

The conceit of the book is that the narrator, who, like the author, is named Charles Yu, repairs time machines, which his estranged father invented. We are treated to a hilarious send-up of the usual fodder of such books (getting caught in a time loop, the dangers of altering the past in ways that will affect the present, and even an invocation of the multiple universes of string theory), but as we read on we see that the underlying human drama is at the center of the novel. The narrator’s father, who suffered from lack of success, disappears in a time trip, and the son struggles to find him. It is deeply affecting.

Give this one a try–and if you don’t like it, what can I say? Some people don’t like Henry James, and James is none the worse for it.

Jill O’Neill: While I didn’t read as much in 2015 as in previous years, when I looked over what I had completed across the past twelve months, I discovered there’d been a consistent (and somewhat unintentional) theme to the books I’d not just read, but also managed to retain in my memory. All had to do with various experts discussing (if not always justifying) their own reading selections. Among other titles, I read Phyllis Rose’s The Shelf : From LEQ to LES: Adventures in Extreme Reading, John Carey’s The Unexpected Professor: An Oxford Life in Books, and Michael Dirda’s Browsings: A Year of Reading, Collecting, and Living With Books. So, just as with this collaborative post’s theme of naming “Best Books”, focus for me this year was on the question of what was worth reading.

Jill O’Neill: While I didn’t read as much in 2015 as in previous years, when I looked over what I had completed across the past twelve months, I discovered there’d been a consistent (and somewhat unintentional) theme to the books I’d not just read, but also managed to retain in my memory. All had to do with various experts discussing (if not always justifying) their own reading selections. Among other titles, I read Phyllis Rose’s The Shelf : From LEQ to LES: Adventures in Extreme Reading, John Carey’s The Unexpected Professor: An Oxford Life in Books, and Michael Dirda’s Browsings: A Year of Reading, Collecting, and Living With Books. So, just as with this collaborative post’s theme of naming “Best Books”, focus for me this year was on the question of what was worth reading.

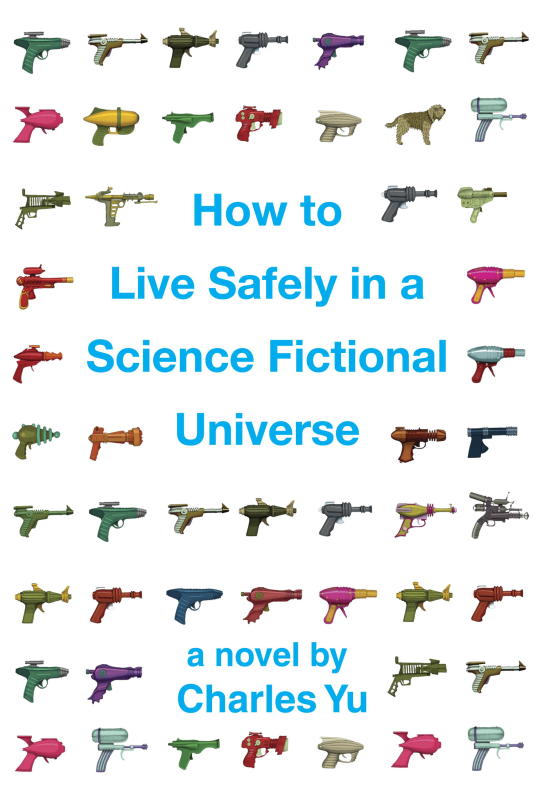

My most enjoyable and substantive reading experience in that vein was The Golden Age of Murder by Martin Edwards. Edwards isn’t an academic, but rather a crime novelist, a member of the UK-based Detection Club and its very first archivist. While that club’s name may ring only a faint bell in the back of your brain, the Detection Club was founded in London in 1930 by Anthony Berkeley, Agatha Christie, and Dorothy L. Sayers and continues to be a critical social and professional network for writers of the British crime novel. Edwards focuses primarily on the initial years of the organization and its founders, but notes the impact of the Detection Club on the genre in print, television and film up to the present day. Its members, in Edwards’ words, “did more than simply respect tradition…they developed detective fiction in ways that lasted much longer than anyone expected”. More than 500 pages in length, the book serves as both a literary and social history of the development of the British crime novel. There are a host of names included here — some, such as Christie, that are immediately recognizable and others, such as E.R. Punshon, whose works are known perhaps only to those who read deeply within the genre. Edwards references the real crimes and historical events that influenced works by these writers as well as impacting on their private lives. Who knew that Agatha Christie came under suspicion of treason in World War II? Edwards probes into the Golden Age of the British crime novel without overly sanitizing the behaviors and attitudes of key players. I’ve been leading mystery discussion groups at local libraries for more than 25 years and yet, I found this to be an informative (as well as refreshingly candid) account of a period and genre I had always thought I knew relatively well.

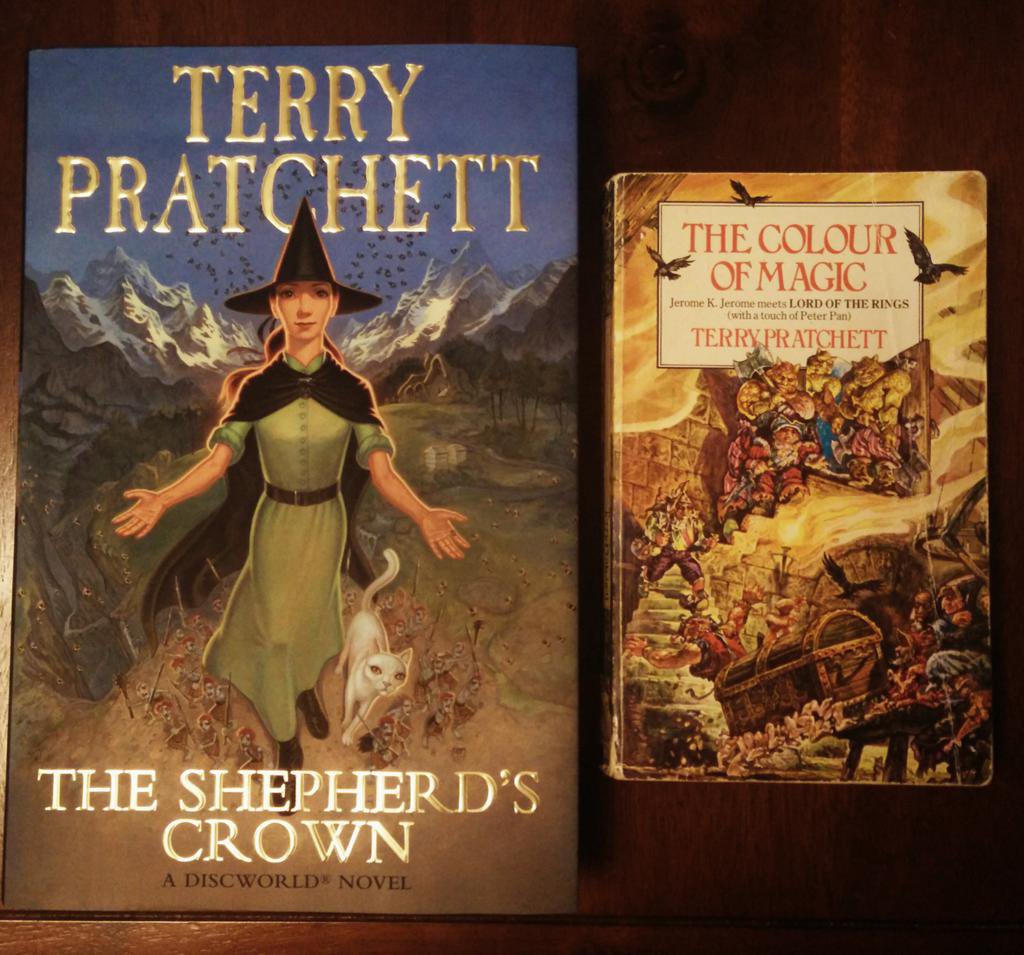

David Smith: The attached image is released under a CC-BY-NC license with a special commercial use exception granted for the Scholarly Kitchen / SSP should it ever be wanted 🙂 It was taken by a primate.

David Smith: The attached image is released under a CC-BY-NC license with a special commercial use exception granted for the Scholarly Kitchen / SSP should it ever be wanted 🙂 It was taken by a primate.

It was 1985. It was wet. It was a Saturday. It was the West Midlands and we had four channels of TV, no cable or satellite, and because it was always the West Midlands on a wet Saturday in 1985, and our particular TV could only pick up three channels*, I was a reader of books on an epic scale. Because of all these things, and because by some strange quirk of fate my pocket money was always sufficient to buy a paperback book AND save a quid, I found myself inevitably in WH Smiths, Looking for some ‘long form entertainment’. The cover of one particular book caught my eye. Utterly different to everything else around it. There was a chest. With lots of legs. And on the back…

THE WACKIEST AND MOST ORIGINAL FANTASY SINCE HITCHHIKER’S GUIDE TO THE GALAXY

Wet Saturday or not, there was no higher praise than to be compared to Hitchhiker’s. Sold, to the kid with glasses. £1.75 to you young sir.

I was hooked by the tenth paragraph, spluttering and chuckling with laughter, sitting in the back seat of the car on the way home; the smell of a freshly cooked loaf of bread on the parcel shelf soaking my synapses simultaneously with the words of Terry Pratchett’s First Discworld novel; The Color of Magic.

We rode together, Terry and me. Forty one journeys around a planet where there are eight colors, where Death likes a curry, where a sock wrapped around a brick can get you out of some very tricky situations and dogs can talk and computers can have ‘out of cheese errors’ and you DO NOT MESS WITH THE LIBRARIAN (but a well-placed banana does wonders) and… Well if you don’t know of these things, do yourself a real big favor and start at the beginning, with Rincewind and Twoflower and The Luggage.

Alzheimer’s took him. Dammit. But he was still writing up until the end apparently. His last book (my book of the year) was The Shepherd’s Crown. You can’t review it critically. Too many rides together. Hard to read to be honest, each page turned taking you closer to the truth that there are no more words to come from this world that rests on Berilia, Tubul, Great T’Phon and Jerakeen; carried forward into that good night by Great A’Tuin.

I firmly believe that if this country of mine has any sense, the years to come will mean that children will read Pratchett, like we read Dickens. He will be studied. Earnest young men (mostly, but hey, earnest young ladies too) probably with beards (not the ladies) will write Ph.D.’s on his works. They should anyway, for he was that good an observer of our world, and the refractive qualities of his writing repay every return.

Sir Terry Pratchett. I will miss you. Thank you for the footnotes that went on for pages, the friends and foes met along the way. Thank you for the stories.

*The dark side of late night Channel Four** was something one could only hear about by that strange osmosis of faction that occurs in the School Playground

**There was this red triangle that would show up on foreign films, late on a Friday night. Films with subtitles. Films starring Catherine Deneuve.

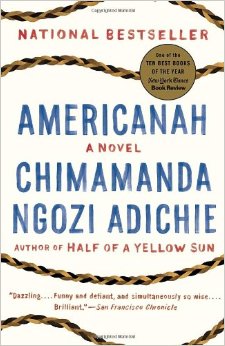

Alice Meadows: My pick this year is Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It’s a beautifully written story of two young Nigerians — Ifemelu and Obinze — who leave their homeland for the US and UK respectively; of their experiences there and how they affect them each personally, as well as their relationship with each other, and with their families and friends. In addition to tackling the issue of racism (including the subtle — and not so subtle — differences between racism in each country), Adichie writes powerfully about the sense of displacement Ifemelu, in particular, feels — both in her adopted country and, to her surprise and disappointment, when she returns ‘home’. In Nigeria, she’s one of the popular girls, but in America she faces years of feeling homesick, alien, and alienated, before feeling at home. Ultimately, however, she finds she doesn’t fully ‘belong’ anywhere — not in her circle of mostly African American friends in the US, nor among the American African diaspora, nor in Nigeria, when she finally returns there. It’s a feeling I very much relate to, having spent most of my life in the UK before moving — as it turns out, permanently — to the US 15 years ago. But you don’t have to have ever left your homeland to enjoy this book – it’s both a fascinating look at the complex issues of race and identity, and a compelling story that draws you into the lives of its characters.

Alice Meadows: My pick this year is Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. It’s a beautifully written story of two young Nigerians — Ifemelu and Obinze — who leave their homeland for the US and UK respectively; of their experiences there and how they affect them each personally, as well as their relationship with each other, and with their families and friends. In addition to tackling the issue of racism (including the subtle — and not so subtle — differences between racism in each country), Adichie writes powerfully about the sense of displacement Ifemelu, in particular, feels — both in her adopted country and, to her surprise and disappointment, when she returns ‘home’. In Nigeria, she’s one of the popular girls, but in America she faces years of feeling homesick, alien, and alienated, before feeling at home. Ultimately, however, she finds she doesn’t fully ‘belong’ anywhere — not in her circle of mostly African American friends in the US, nor among the American African diaspora, nor in Nigeria, when she finally returns there. It’s a feeling I very much relate to, having spent most of my life in the UK before moving — as it turns out, permanently — to the US 15 years ago. But you don’t have to have ever left your homeland to enjoy this book – it’s both a fascinating look at the complex issues of race and identity, and a compelling story that draws you into the lives of its characters.

Discussion

10 Thoughts on "Chefs’ Selections: The Best Books Read During 2015 Part 1"

The Terry Pratchett series on Tiffany Aching is one of my all-time favorite. The audio books are the best way to enjoy them! I agree these books will make an impact on future studies of the written language. Happy reading – er, listening.

You forgot to mention that Terry Pratchett should have won the Nobel Prize for Economics for the Sam Vimes “Boots” Theory of Socioeconomic Unfairness,

The reason that the rich were so rich, Vimes reasoned, was because they managed to spend less money.

Take boots, for example. He earned thirty-eight dollars a month plus allowances. A really good pair of leather boots cost fifty dollars. But an affordable pair of boots, which were sort of OK for a season or two and then leaked like hell when the cardboard gave out, cost about ten dollars. Those were the kind of boots Vimes always bought, and wore until the soles were so thin that he could tell where he was in Ankh-Morpork on a foggy night by the feel of the cobbles.

But the thing was that good boots lasted for years and years. A man who could afford fifty dollars had a pair of boots that’d still be keeping his feet dry in ten years’ time, while the poor man who could only afford cheap boots would have spent a hundred dollars on boots in the same time and would still have wet feet.

This was the Captain Samuel Vimes ‘Boots’ theory of socioeconomic unfairness.

That’s one of the bits that’s stuck with me from my earliest exposure to Pratchett, too. I have been using Sam Vimes’s “Boots” theory for at least two decades now to explain, among other things, why I quit buying $15 dress shoes and why it’s so expensive to be poor.

Everyone in book publishing should read Robert Spoo’s masterful book titled “Without Copyrights: Piracy, Publishing, and the Public Domain” (Oxford, 2013). Not only will you learn about how the US benefited from pirating works from abroad but also how we might go about constructing a more coherent system of copyright protection in today’s world. My review of the book appeared in the October issue of the Journal of Scholarly Publishing. My Green OA version is posted here: https://scholarsphere.psu.edu/files/6q182k142. You will also find the DOI for the version of record in the metadata there.

Terry Pratchett was the Jonathan Swift of our time. And you could tell he was getting increasingly angry at injustice as time went on, but that never stopped him from telling tales with humor. If you like Pratchett then you’ll probably like “Who Goes Here?” by Bob Shaw. One of the funniest books I’ve ever read (and sadly out of print the last time I checked). You join the Space Foreign Legion to forget, literally, as they have a memory erasing machine, but what did you do that would cause you to wipe your whole memory? Comic mishaps ensue.

The other book which has struck and left me thinking for days afterwards is “Blindsight” by Peter Watts. A really disturbing tale of how can we really communicate with aliens if they are really alien.