Continuing an annual tradition, we take a moment to pause at year’s end to look back on the best books we encountered. As always, this is not a “best books of 2015″ list, but a list of the best books the Chefs read during 2015 — the books might be classics, a few years old, or brand new. This is one of the great things about books in all forms — they endure, invite visitation and revisitation, and beckon with ideas. Here’s Part 2 of our list, Part 1 can be found here.

Karin Wulf: There are so many different kinds of “best books.” There are books that stick with you because the themes and the language are so evocative. There are books that you’re glad to see published and then read because they articulate issues that you didn’t even know you were trying to think about. And then there are books that seem particularly urgent, that punctuate developments gaining currency and momentum.

Karin Wulf: There are so many different kinds of “best books.” There are books that stick with you because the themes and the language are so evocative. There are books that you’re glad to see published and then read because they articulate issues that you didn’t even know you were trying to think about. And then there are books that seem particularly urgent, that punctuate developments gaining currency and momentum.

My favorite read this year is in this last category. It’s a book that has historicity — it is of a moment, but it also resurrects a forgotten, in fact trampled, historical past. Steve Silberman’s Neurotribes: The Legacy of Autism and the Future of Neurodiversity is not a history of autism; it is, rather, an account of how we came to diagnose particular qualities, characteristics and experiences as “autism,” and what that diagnosis then came to mean over time. Silberman returns to the work of Hans Asperger, Leo Kahner and others to show how ideas about autism evolved, changed, and devolved over the twentieth and into the twenty-first centuries.

Neurotribes also makes a critical comment on issues we care a lot about here at the Kitchen — failed peer review, bad science, and what happens when policy and money run with rather than against them. Infamously, a not only flawed but intentionally corrupt study linked autism with vaccines. That played an important part, as Silberman illustrates, in the hysteria over an “autism epidemic.” The best studies show clearly that autism is not on the rise, but that the use of newer and more sensitive diagnostic instruments account for increases in rates of autism.

While Neurotribes is the work of many years of research and writing by one journalist, it is also the product of a movement of autistic activists who have been arguing for a new understanding of brain differences. Rather then pathologies to be cured, or prevented, brain differences should be understood as part of natural human differentiation. This perspective does not discount the reality of disability, but it does change the focus from research into causes and cures to support for autistic children and adults and their families. It’s becoming (almost?) a commonplace that disability is the next civil rights frontier. It is Silberman’s genius to both trace a long and complicated medical history and yet to show so compellingly how that frontier is right here, right now.

David Crotty: The summer of 2015 was, in my household, a summer of baseball. My beloved and beleaguered Mets surprised everyone by being a year or two ahead of expectations and making it all the way to the World Series before running into the Royals and their seeming ability to continually rise from the dead. It was also the year when my son grew old enough to start appreciating baseball and I got to enjoy the sublime pleasure of taking him to his first game. We frequented ballparks, minor and major league, throughout the season.

David Crotty: The summer of 2015 was, in my household, a summer of baseball. My beloved and beleaguered Mets surprised everyone by being a year or two ahead of expectations and making it all the way to the World Series before running into the Royals and their seeming ability to continually rise from the dead. It was also the year when my son grew old enough to start appreciating baseball and I got to enjoy the sublime pleasure of taking him to his first game. We frequented ballparks, minor and major league, throughout the season.

For me, baseball is about two things that fascinate me, history and math. The careful records kept and the nearly endless ways of analyzing the data remain interesting. But for me the real draw is in the stories. Baseball is inextricably intertwined with the history of the United States from the late 1800s to the present day (and its replacement by football as the national pastime is surely a signifier of our move to a less elegant and much more violent world). Summer reading always, at some point, turns to baseball reading and the cornucopia of superb books on the game, from classics like Roger Kahn’s The Boys of Summer to Cait Murphy’s sprawling Crazy ’08, to Jim Bouton’s rollicking Ball Four to Jane Leavy’s superb biography of the zen master Sandy Koufax. But the greatest of them all, and a book I find myself regularly turning to, is Lawrence Ritter’s The Glory of Their Times.

Originally published in 1966, Ritter realized at the time that an entire generation of baseball players was growing older and dying off, and that the opportunity to hear their stories would soon be at an end. He traveled more than 75,000 miles to find them, no easy task in a time when there were no centralized sources of information, no pension records (nor in most cases social security) to track, and little contact with their original clubs. Remember, this was an era of low salaries, when players had jobs during the offseason, and when they retired from the sport, they had to find new careers. Ritter lugged a tape recorder around the country and captured the experiences of players from the early 1900s through the early 1940s, including Wahoo Sam Crawford, Smokey Joe Wood, Goose Goslin, Babe Herman and the original Hammerin’ Hank Greenberg (why, oh why do we no longer give players nicknames like these?).

You get stories of the great games and great players from the early days of the sport as well as an indelible picture of the times. Young mens’ lives were transformed as they narrowly escaped a short and brutal life in the local coalmine, and instead came to the big city, wearing the one suit their entire family owned, carrying all their possessions in a cardboard suitcase, at first earning fitting nicknames like “Rube” and later a nation’s adulation. The book is filled with photographs and is, as the title implies glorious. If you only want to read one book to understand baseball and the important role it played in forming America’s character and mythology, this is the one.

Robert Harington: My favorite book of the year is Play it Again: an Amateur Against the Impossible by Alan Rusbridger. The book was recommended to me by Mark Ware. I gather Mark read this in furious delight over a weekend – it took me much longer. So why was this the book that captivated my 2015? The author, Alan Rusbridger, is a household name in the UK. In October 2015 he became Principal at Lady Margaret Hall College in Oxford. When he wrote this book he was firmly installed at The Guardian as Editor in Chief. If you are an amateur musician you will identify with this book. Rusbridger describes his adventure with attempting to climb the summit of learning and performing Chopin’s “Ballade No.1 in G Minor”. His journey begins at a summer camp in France’s Lot Valley when he heard a remarkable performance of the Ballade and decides that he too will master the piece and keep a diary of his progress.

Robert Harington: My favorite book of the year is Play it Again: an Amateur Against the Impossible by Alan Rusbridger. The book was recommended to me by Mark Ware. I gather Mark read this in furious delight over a weekend – it took me much longer. So why was this the book that captivated my 2015? The author, Alan Rusbridger, is a household name in the UK. In October 2015 he became Principal at Lady Margaret Hall College in Oxford. When he wrote this book he was firmly installed at The Guardian as Editor in Chief. If you are an amateur musician you will identify with this book. Rusbridger describes his adventure with attempting to climb the summit of learning and performing Chopin’s “Ballade No.1 in G Minor”. His journey begins at a summer camp in France’s Lot Valley when he heard a remarkable performance of the Ballade and decides that he too will master the piece and keep a diary of his progress.

This is one of those pieces that needs conquering. It is a fascinatingly complex piece, especially the end in the coda. As Rusbridger says “Not only is it implied that the player should surmount these challenges; they must do so with seeming nonchalance.”

The book reads as a thriller. Rusbridger gives himself a year to be able to learn this piece to performance standard. Layered over his musical voyage of discovery is the day job. This was a time when The Guardian was actively involved with Julian Assange and WikiLeaks, breaking stories of state secrets. It was also the year when The Guardian broke stories of the News of the World phone hacking scandal. How can Rusbridger find time and energy to play music amidst the pressures of the day job?

The book is warm and human. You gain a palpable sense of his love for the piano, how he relishes his amateur musician status, and his desire to overcome his fears and play the Ballade. He tells stories of his hunt for the perfect piano for his new music room in his country cottage – Fish Cottage – in the village of Blockley in North Gloucestershire. He interviews some of piano’s musical giants on their views on the Ballade. Murray Perahia insists that Rusbridger must have a story in his mind for the piece. “He tells me that the Ballade story is split into three basic parts: a sense of enslavement, present exile, future rebirth.” On the other hand Emanuel Ax suggests that it is not a story that can be put into words. “I think there is definitely a narrative in this piece, as you do in all others, but I think this one is so multifaceted.” Rusbridger also delves into science, interviewing Ray Dolan, FRS, Professor of Neuropsychiatry at University College London. We learn about memory and how there are two types of memory implicit and explicit. Implicit memories are most often procedural. When you play and your fingers almost automatically move to the right place this is procedural memory at work. There is also the more explicit memory, for example, what time did I practice yesterday? This is located in the hippocampus. You can learn a piece, but much of what you do when playing is also procedural and in between you can color the music.

Perhaps the most important thing I learned from the book is that practicing (in my case a cello) early in the morning leaves you more ready to deal with the onslaught of the day. This is now a part of my day and I can tell you it works, though the constant whistling of the tunes in my head may be an annoyance for everyone around me.

Rick Anderson: This year I belatedly read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. I’m kind of a sucker for dystopian novels, especially those written several decades ago (this one is from 1985). I enjoy seeing what authors of that time period thought the future was going to look like, and I enjoy feeling smug that things aren’t as bad as they envisioned. And I also kind of enjoy the slight frisson of dread that comes when I see the occasional things they predicted correctly, and appreciate the heightened sense of vigilance that the best of these books inspire as I look around me at the way some things are going. When all of this intellectual utility is presented in the context of a beautiful prose style and an artfully unfolding narrative structure, all the better. I expect to be reading more Atwood shortly.

Rick Anderson: This year I belatedly read Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. I’m kind of a sucker for dystopian novels, especially those written several decades ago (this one is from 1985). I enjoy seeing what authors of that time period thought the future was going to look like, and I enjoy feeling smug that things aren’t as bad as they envisioned. And I also kind of enjoy the slight frisson of dread that comes when I see the occasional things they predicted correctly, and appreciate the heightened sense of vigilance that the best of these books inspire as I look around me at the way some things are going. When all of this intellectual utility is presented in the context of a beautiful prose style and an artfully unfolding narrative structure, all the better. I expect to be reading more Atwood shortly.

Charlie Rapple: My non-fiction choice from the books I read in 2015 is Breakfast at Sotheby’s by Philip Hook. It unites two of my life’s most prevailing interests, art and business, with a set of easy-to-read essays about how art is valued / becomes valuable. There are fascinating insights (sunny pictures raise more at auction than rainy ones, happy pictures more than sad ones, serene ones rather than wartorn ones) and thoughtful analysis of artist’s “brands” (ultimately, the more thematic and recognizable your works, the more you increase the price of your overall oeuvre). The book closes with an entertaining “plain language” glossary of what elitist art terminology really means. A great collection to dip in and out of.

Charlie Rapple: My non-fiction choice from the books I read in 2015 is Breakfast at Sotheby’s by Philip Hook. It unites two of my life’s most prevailing interests, art and business, with a set of easy-to-read essays about how art is valued / becomes valuable. There are fascinating insights (sunny pictures raise more at auction than rainy ones, happy pictures more than sad ones, serene ones rather than wartorn ones) and thoughtful analysis of artist’s “brands” (ultimately, the more thematic and recognizable your works, the more you increase the price of your overall oeuvre). The book closes with an entertaining “plain language” glossary of what elitist art terminology really means. A great collection to dip in and out of.

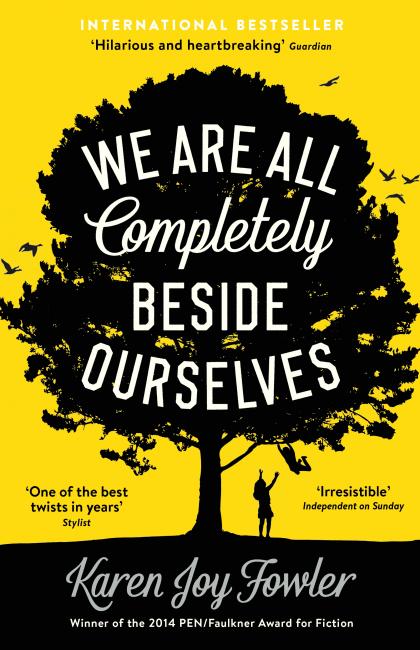

Meanwhile on the non-fiction front, the most memorable book for me this year was We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler. Effectively a family memoir, the story is absorbing even before you get to its excellent twist – well written, with a likeably self-aware first person narrator and a tantalising connection with an infamous real-world psychology experiment. It is a warm and witty portrait of childhood disruption (even trauma) and lifelong repercussions.

Meanwhile on the non-fiction front, the most memorable book for me this year was We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler. Effectively a family memoir, the story is absorbing even before you get to its excellent twist – well written, with a likeably self-aware first person narrator and a tantalising connection with an infamous real-world psychology experiment. It is a warm and witty portrait of childhood disruption (even trauma) and lifelong repercussions.

Discussion

1 Thought on "Chefs’ Selections: The Best Books Read During 2015 Part 2"