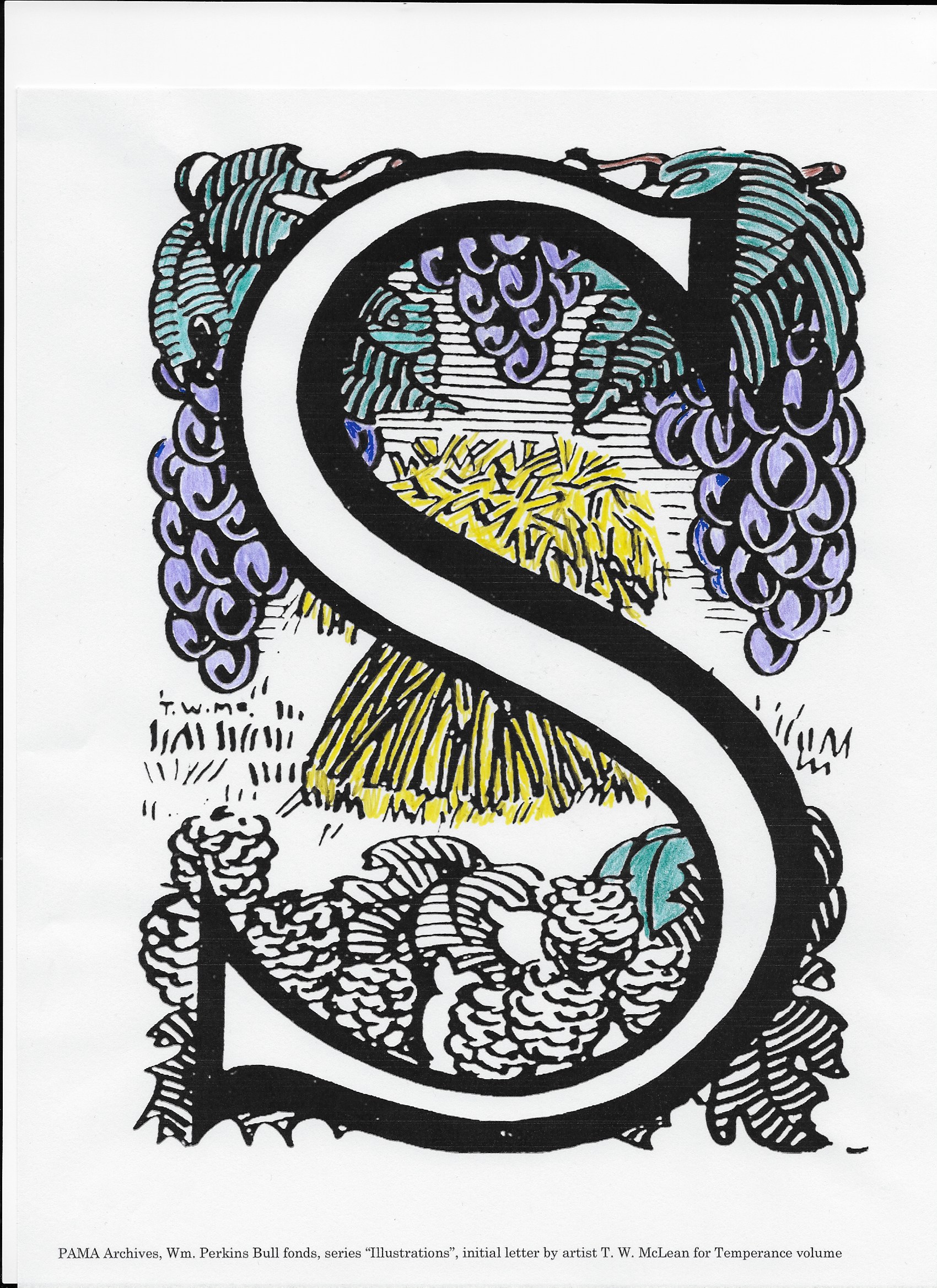

The campaign appeared on Twitter as #ColorOurCollections. An exchange between the New York Academy of Medical History and the Biodiversity Heritage Library sparked enthusiasm for a rapidly produced and freely delivered offering of black and white images suitable for adults to use in the stress-reducing activity of coloring, a well-documented trend. Subsequently, an array of more than 100 museums and archives released images from their collections during the week of Feb 1-5.

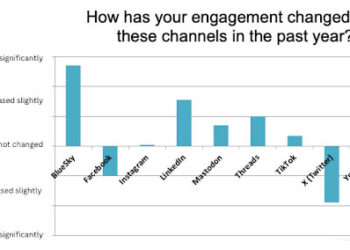

While the hashtag didn’t rise to the status of a trending topic on Twitter, as social media campaigns go these days, #ColorOurCollections was tremendously successful. The page listing institutional participants on the Open Culture blog had clocked 7,800 shares by the end of the week. Images poured out from a truly diverse assortment of institutional collections, including but not restricted to the Linda Hall Library, Harvard’s Chandra Observatory, Swarthmore College, the Chemical Heritage Foundation and the LBJ Presidential Library. Every major social network saw its share of traffic — Tumblr, Facebook, Instagram and more. Professional and personal blogs further publicized the campaign.

It was also a cross-disciplinary effort — as likely to feature medieval images as those from 19th century anatomical reference books, a miscellanea of plants. advertisements, architectural details, and even patents. The coloring books differed in size; the PDF file posted by James Madison University contained a generous collection of more than fifty illustrations from children’s books whereas the eight-page book from the Smithsonian Institute included abstract design images. The Massachusetts Historical Society sponsored a coloring competition, inviting participants to color in an image actually drawn by an 1835 automaton. The Folger Shakespeare Library suggested that one might color a playbill for Hamlet, while the University of Glasgow included a poster promoting a 1968 production of one of William Congreve’s plays, The Way of the World. The Bodleian used the opportunity to promote recently digitized images from its Polonsky Project.

There are any number of ways of viewing this initiative. It was a quick and easy public relations campaign for the cultural heritage community, enlivening otherwise mundane (read text-heavy) feeds appearing on Twitter and Facebook. It served to heighten the visibility of and access to special collections that might solely be seen otherwise as the primary concern of specialists. And it cleverly leveraged a pre-existing popular trend for adults in order to do so.

Building engagement is a tricky process for anyone attempting to build interest in archival or special collections. In the current data-driven age, it is also an imperative that those responsible be able to demonstrate community engagement with special collections and thereby justify an ongoing investment by the parent institution. The Color Our Collection campaign offered some key benefits to libraries, archives and museums as it:

- provided greater visibility for the participating institutions;

- enabled broader awareness and closer examination of otherwise hidden assets held in a collection;

- fostered re-use of the object or asset, without threat of damage or diminishing of its long-term value to the research community;

- and continues to support tracking and assessment of the public’s engagement (via click-throughs, downloads, etc.) with materials held in trust by both public and private libraries, archives, and museums.

There’s a certain degree of re-training happening here. For many, the library is associated with books — collections of volumes, images and text bound together. However, when presented with images like these from those same hidden or obscure collections, separated from their original context, individual users may begin to view the library as a more complex and creative resource. That’s a useful shift in perception. In the main, when we think of information resources, a unified and ordered presentation (like that found in books, journals or even classification schemes) is the highly-valued norm. The counterweight is the notion that creativity springs primarily from chaos, a quality not generally associated with libraries or archives. When libraries figuratively rip a page from one of their treasures and urge users to color in the margins, that too breaks down a limited perception of what the library offers. Is it any wonder that so many libraries are looking to show themselves as maker spaces?

The whole initiative reminded me of something I’d seen emanating from ALA/ACRL’s outstanding Rare Books and Manuscripts Division conference in 2015. I wasn’t attending in person, but I was following the Tweet stream (#rbms15). In the event’s closing plenary, Rick Prelinger of the unique Prelinger Library talked about the need to open up archives and special collections to those who are not members of an elite research community. His talk was followed up by one from Stanford historian, Gordon H. Chang; the key message from both experts being neatly summarized by Chris Bourg of MIT when she tweeted out “The humanities are in crisis because we are talking to fewer and fewer people; the answer is to talk to new communities and collaborate”.

At a casual glance, #Color Our Collections appears to be a somewhat frivolous re-purposing of content. Given due consideration, it proves not to be frivolous at all. As an initiative, it met without question the challenge tweeted by Bourg; it spoke to new communities and was the fruit of collaborative effort.

The question for any content provider (whether they be called by the traditional name of publisher, librarian, curator or archivist) should be how best to foster and support re-use of a collection, that critical mass of content representing an archival record. For a week, these institutions took the lead in doing so.

Discussion

4 Thoughts on "What #ColorOurCollections Suggests"

Isn’t opening up archives and special collections one of the main aims of the DPLA and of other consortia like HathiTrust?

Of course! But what strikes me about this particular campaign was the swiftness with which it was pulled together in the context of social media. A conversation on Twitter blossomed into a very positive campaign that allowed libraries, archives and museums to catch the attention of the ordinary user who might (quite honestly) never have heard of the HathiTrust or the DPLA. It’s not a criticism of those organizations. it’s just that this initiative came together and worked for many of these institutions on a very grass-roots level.