There was big news a few weeks back in the Humanities and Social Science community when it was announced that Elsevier purchased SSRN — a popular preprint server for this area of research. There was much wringing of hands by some users of SSRN, despite Elsevier’s assurances that the site would remain largely as it exists. All SSRN staff will be maintained and it will still be free to post and free to read.

SSRN has nearly 640,000 articles and last month promoted over 100 million downloads. This is not small potatoes and much has been written about the strategic advantage that owning a large preprint server gives to any commercial publisher.

It’s important to note that the objection to Elsevier’s acquisition of SSRN is exactly that Elsevier is the purchaser. SSRN was a for-profit entity before Elsevier entered the picture.

Adding more fuel to the fire of the former SSRN supporters, some users have found that their posted PDFs were removed recently due to copyright concerns. It appears that some of these removals may have been in error but just as many that have hit the public eye seem justified.

Scholarly Kitchen readers know this but I’ll state it again. Authors may not legally post versions of content that they do not have the right to post. Each publisher can/will have different policies around what can be shared on an unrestricted website. Generally speaking, authors are free to do whatever they want with the author’s original version (preprint version) of their manuscript, and permitted to share the accepted manuscript version of their published papers after an embargo and with some restrictions on commercial use. Unless the paper is under a license that allows the final published version of record to be posted online, this is typically not allowed without a licensing arrangement, such as paying for open access, or the host site signing a deal with the paper’s publisher.

So back to SSRN — much like when Elsevier purchased Mendeley, a clean-up of materials posted in violation of copyright is going to happen. Because Elsevier has their own set of article sharing policies which they expect others to follow, so too they make all efforts to follow the policies of other publishers.

Some folks are complaining that this is a change to the SSRN policies. In the May 2016 announcement of the sale of SSRN to Elsevier, SSRN Chairman Michael C. Jensen wrote, “and our copyright policies are not in conflict — our policy has always been to host only papers that do not infringe on copyrights.”

The SSRN Terms of Use that appear to be unchanged since the announcement of the sale state:

Copyright and Trade Marks: Any person who provides any material for inclusion on SSRN is responsible for ensuring that this material does not violate other parties’ copyright or other proprietary rights and does not otherwise violate law or applicable SSRN policy. As part of its general right to remove material, SSEP reserves the right in its sole discretion to delete or make inaccessible files that do or may contain material that violates law, or applicable SSRN policy, or the rights of third parties.

What seems to have changed is not the policy but the desire to enforce the policy. Safe Harbor laws allow websites to claim ignorance when copyrighted material is posted on their pages by random users. However, once the legal copyright holder notifies the site that materials under their copyright are posted, the site is required to remove it in a timely manner.

According to SSRN on the post linked above, they are taking steps to review papers at submission for any potential copyright violation. Users of SSRN on the same discussion board would rather SSRN allow these materials to be posted and wait for the copyright owner to send a take-down notice.

In the wake of these pseudo-controversies, we have SocArXiv. While it has been stated that SocArXiv was in the works prior to the announcement of the SSRN sale to Elsevier, their timing could not be better. They are hoping to capitalize on the growing discontent with SSRN.

SocArXiv was described by founder Philip Cohen of the University of Maryland as such:

… there remains a need for a new general, open-access, open-source, paper server for the social sciences, one that encourages linking and sharing data and code, that serves its research to an open metadata system, and that provides the foundation for a post-publication review system. Once it’s built, anyone will be able to use it to organize their own peer-review community, to select and publish papers (though not exclusively), to review and comment on each other’s work — and to discover, cite, value, and share research unimpeded.

SocArXiv is built on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, though the current site is labeled as “temporary.” The University of Maryland, where Cohen is employed, is called a “host.” In this interview with Richard Poynder, Cohen called it a “Program of the University of Maryland.” On the University of Maryland site, you can make a donation to support it. In the future, Cohen explained, the hope is that universities and research agencies will fund the project along with the grants and funding that OSF gets through the Center for Open Science. The cost for maintaining the site will not be insignificant. Annual operating expenses for arXiv, albeit a much larger site serving primarily physics, are reportedly over $820,000 and a new fundraising campaign is underway to grow capital for improvements. Funding for physics has been higher than for social sciences so it’s not clear that grants will be as plentiful for funding SocArXiv.

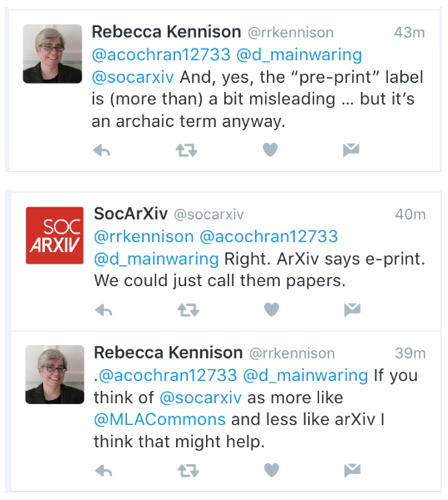

Despite the descriptions, there was some confusion that arose last week when it was pointed out to SocArXiv that they were hosting the final PDF of a paper under copyright with Taylor & Francis. A discussion with Rebecca Kennison (a member of the SocArXiv steering committee) the SocArXive official Twitter handle, myself, and others ensued and things got a little murky. Here is what was said:

On the subject of whether anyone at SocArXiv is checking material before it is posted, the answer is no — not at this time. Okay, but the ingestion process does seem to indicate that there are human beings involved. I submitted a paper, which is done entirely by email. The requirements for the email are to include the title of the paper in the subject line and then the abstract in the body with the paper attached. In my profile, my affiliation information was parsed from the email signature line and the paper. An affiliation is not a required element of the submission email.

It is possible that there is an automated ingestion process pulling these things into the system but that seems unlikely given that the affiliation was not a requirement in the email and that is the one that was used to create my account.

As stated earlier, SocArXiv is running off the OSF Preprints platform, which is listed as “coming soon” on the OSF site. The not-yet-available nature of the platform means that there isn’t a lot of information about how it works.

If there is a person actually processing papers, one would think that a check on whether the user has the authority to post the attachments sent would be part of the check, thus avoiding the final published PDFs of articles.

As of today, the T&F paper is still posted. Kennison stated that SocArXiv “will respect all legitimate take-down notices” but went on to say that in her personal opinion publishers have to “prove they have copyright, not just claim they do.” By law, the requirements for a “legitimate take-down notice” do not require such proof.

Using “terms of use” to avoid copyright infringement and evoking safe harbor laws in refusing to remove copyrighted materials is a risky proposition for a website that is described by its founder as “program” of a major university.

This conversation evolved to another question. If SocArXiv is a preprint server, why would there be published papers? This was the response:

So despite the fact that it’s called a preprint server here, here, and six times on the submission page, it’s not a preprint server. It’s an archive that will host anything a user wants to post and eventually, you can add comments (a.k.a. post-publication peer review).

The other touted benefit is that users receive a persistent ID for citations. The persistent ID is a URL. Here is mine: https://osf.io/d2kz9/. Given that every description of the site says that the OSF Preprints is a “temporary” home, where will it go and what will happen to these persistent identifiers? One of the main reasons we use DOIs as persistent identifiers is because of the transitory nature of URLs.

I have to say, this feels like a hasty launch. Cohen said that the plans were in the works well before SSRN’s sale to Elsevier was announced and I have no doubt that this is true. We don’t know what the status of the plan was at the time of the announcement. But the entire thing does not seem ready for prime time. If OSF’s platform was not ready, which seems to be the case with the entire OSF Preprint platform labeled as “coming soon”, then what was the rush?

I believe that the answer is Elsevier. The steering committee for SocArXiv have some really grand plans and the use of the OSF platform creates an end-to-end solution — maybe. Having one platform for project plans, data, figures, presentations, preprints, and (ambitiously) post-publication reviews that are accepted by the community in lieu of journal articles could be a game changer in the future. But me “getting” this, required two days of research to figure out why things didn’t seem to be what they were called.

The confused launch and blurry vision may slow the ambitions of SocArXiv. There are other alternatives for those no longer enamored by SSRN (despite its new infusion of cash that will sustain and likely add functionality to the site). In the meantime, as with any new endeavor, I would suggest that authors proceed with caution and keep back-up copies. This project will be one to watch.

Discussion

38 Thoughts on "What Is SocArXiv?"

Corrections and clarifications. All of this could have been easily cleared up if Angela had opted to contact us before posting this.

>> SocArXiv is built on the Open Science Framework (OSF) platform, though the current site is labeled as “temporary.” The University of Maryland, where Cohen is employed, is called a “host.”

The site is not “temporary,” the deposit and search interface are temporary. The use of “though” in the sentence above is just to cast unsubstantiated doubt. The University of Maryland is hosting the program, not the server, obviously.

>> The cost for maintaining the site will not be insignificant. Annual operating expenses for arXiv, albeit a much larger site serving primarily physics, are reportedly …

The Open Science Framework, the system on which SocArXiv runs, also has a large budget devoted to development, operation, and maintenance of this infrastructure. Of course, we will need to raise money.

>> On the subject of whether anyone at SocArXiv is checking material before it is posted, the answer is no — not at this time. Okay, but the ingestion process does seem to indicate that there are human beings involved. I submitted a paper, which is done entirely by email. The requirements for the email are to include the title of the paper in the subject line and then the abstract in the body with the paper attached. In my profile, my affiliation information was parsed from the email signature line and the paper.

This is incorrect. The deposit process is automated at this time. It appears that your deposited abstract includes signature file information because it was included in the body of the message. This is something you can edit as the owner of the document. At this moment, your profile (https://osf.io/zr5kb/) does not include any affiliation information.

>> If there is a person actually processing papers, one would think that a check on whether the user has the authority to post the attachments sent would be part of the check, thus avoiding the final published PDFs of articles.

See above for correction. However, it’s worth pausing to ask why “one would think” this. Is the damage caused by ever allowing something without the proper permissions greater than the cost of checking the copyright status of every submission? This should not be assumed. The flap over JAMA claiming copyright status for Obama’s recent article is instructive – copyright status is not as simple as checking for a (c) symbol. I am doubtful that the benefit of this investment would outweigh the harm in the long run. Commercial journal publishers, who exist to enforce copyright protections, may do a lot this work for the community at their own expense. That is just my personal opinion, however. SocArXiv submissions are currently governed by the Open Science Framework terms and conditions, to which each submitting author agrees.

>> Using “terms of use” to avoid copyright infringement and evoking safe harbor laws in refusing to remove copyrighted materials is a risky proposition for a website that is described by its founder as “program” of a major university.

Regarding “refusing to remove copyrighted materials” — readers should be aware that you are not a party to any such discussion, and therefore this characterization is not substantiated.

>> So despite the fact that it’s called a preprint server here, here, and six times on the submission page, it’s not a preprint server. It’s an archive that will host anything a user wants to post and eventually, you can add comments (a.k.a. post-publication peer review).

SocArXiv is a preprint server, and also a server of other things. Nevertheless, the hard distinction between working papers, preprints, and other components of the research process — like the fixation on identifying “versions of record” — is a legacy of the traditional journal publishing system. In fact, research evolves, work is revised as collaboration and feedback lead to new innovations. SocArXiv, by using the Open Science Framework and SHARE and giving persistent identifiers to each component, will help organize and disseminate information about all these components. We are operating in temporary mode at present, and will clarify these terminological distinctions as we move forward.

>> Given that every description of the site says that the OSF Preprints is a “temporary” home, where will it go and what will happen to these persistent identifiers?

The deposit process and search interface, and the landing page where that phrase appears, are temporary. The deposits are persistent, like projects on the Open Science Framework, the system on which it runs. That means that when we upgrade to a more complete interface, the links to deposited materials will not change.

>> I have to say, this feels like a hasty launch. Cohen said that the plans were in the works well before SSRN’s sale to Elsevier was announced and I have no doubt that this is true. We don’t know what the status of the plan was at the time of the announcement.

There is no mystery here. I registered the SocArXiv domains and opened the Twitter account on April 30. That is also when the planning began (I always recommend getting the domain before you start planning). Your site announced the Elsevier acquisition of SSRN on May 17, after which we had a flood of interest and decided to launch the temporary deposit interface. I am proud that we were able to respond to this evolving situation rapidly, but it did not change our overall direction or development.

>> But me “getting” this, required two days of research to figure out why things didn’t seem to be what they were called.

Thank you for your interest. Contacting us (socarxiv@gmail.com) may save time in the future.

>> In the meantime, as with any new endeavor, I would suggest that authors proceed with caution and keep back-up copies.

I hope readers did not need to reach the end of this post to know they should keep copies of their own research. Good advice!

Thank you so much Philip for answering some of the questions. The public face of the site is the submission page, which says “temporary” twice. There is no link on this page to a description of SocArXiv or the business plan or where it will go once it’s not temporary or who is behind it, etc.

I approached the experience as a user and found information to be lacking. I found additional information via Google searches in the blog posts of folks on the steering committee.

For what it’s worth, I am interested to see how this project does going forward. As I said in the post, an end-to-end solution is one that could be a game changer. I think there is confusion between what you say you want to do, and what the only sites available state. This is unfortunate as it confuses your message. You have confirmed that you launched the site as temporary due to interest after the SSRN–Elsevier announcement. There is no link to your message from your submission page. I don’t see the email address above on the site or on the Twitter profile page.

I wish you luck. I think you are on to something interesting if you can keep control of your message.

Regarding “refusing to remove copyrighted materials” — readers should be aware that you are not a party to any such discussion, and therefore this characterization is not substantiated.

Philip, can you tell us whether or not SocArXiv has refused to remove copyrighted materials? If not, then you can clear this up very quickly simply by saying so.

The deposit process and search interface, and the landing page where that phrase appears, are temporary. The deposits are persistent, like projects on the Open Science Framework, the system on which it runs. That means that when we upgrade to a more complete interface, the links to deposited materials will not change.

Can you clarify here? Is the given “persistent identifier” meant just to cover the time period between now and the site moving to its next iteration? Or can you guarantee that the URL given will, for all time, resolve to the item?

Generally the practice is to use things like DOIs which are not subject to problems like link rot. Should the site go under or the deposit move to another service, it would still be findable with a DOI, but not necessarily so with a URL. Are we defining “persistent” differently or is there something I’m missing here?

The persistent links provided are permanent. From the OSF FAQ page:

Data stored on the OSF is backed by a $250,000 preservation fund that will provide for persistence of your data, even if the Center for Open Science runs out of funding. The code base for the OSF is entirely open source, which enables other groups to continue maintaining and expanding it if we aren’t able to.

There’s a difference though, between preservation and discovery. I would hope that OSF does indeed have a robust archiving plan using a service like LOCKSS or one of the others to preserve the permanent record.

The “permanent” URL listed above is at an osf.io address. If OSF ceases to exist, anyone can purchase that domain, and put any webpage they want at that address. The fact that OSF is open source makes no difference here — you can recreate the site elsewhere, but you still need ownership of that domain. My understanding of how preservation systems work is that the material becomes available via the preservation system’s servers, not the original URL.

Which is why we try to use DOIs as persistent identifiers rather than URLs. Web addresses change all the time, but a DOI can be used to resolve to the object in question no matter where its current location.

Again, I admit that I may just be missing something here. Do you have a link to that FAQ list?

This is understood. “Web addresses change all the time” is a slightly extreme statement. Some web addresses change all the time, but those intended to be permanent, created by institutions dedicated to their preservation, with adequate funding and support, do not change all the time. (And of course, DOIs are only “permanent” if someone maintains the infrastructure to find them and serve them.) For more technical discussion, see OSF. Here’s the FAQ page: https://osf.io/faq/.

It’s a nice thought, but sometimes funding runs out or priorities change. Studies have shown that URLS used by researchers (certainly a group that intends their contributions to the scholarly record to be permanent) in their papers are highly subject to link rot:

http://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0115253

US government agencies like CENDI and USGS as but two example suggest the use of DOIs as best practice over the more fleeting URL (https://earth.esa.int/documents/1656065/2265358/CEOS-Persistent-Identifier-Best-Practices and https://www2.usgs.gov/datamanagement/preserve/persistentIDs.php ). Preprint servers like arXiv, bioRxiv and PeerJ Preprints all use DOIs as persistent identifiers for their postings, as does nearly every scholarly publisher on earth.

Relying on URLs seems a bit out of step with best practices, but as noted, I am not an expert in these areas.

Thanks for the links. That PLOS article is a funny thing to cite, since that is mostly demonstrating that publisher-provided links, and links to other external sources that researchers to not control, rot. Naturally.

When you get around to that FAQ, you’ll find the OSF does provide DOIs for research registrations, which is an option for SocArXiv users as well.

Of course, persistence and preservation is a key objective for this project, and we are working with our technology and library partners to make sure we’re doing it right.

I could just as easily have sent you the DOI:

http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0115253

Regardless, I agree that these are really important, and key to building trust in the long term for a project like this. Please don’t take any of this as hostility — I’m happy to see these efforts, and strongly believe that services like this should remain neutral and in the not-for-profit realm, controlled by the research community rather than commercial companies.

Thanks, I appreciate that. What I mean about the PLOS article, though, is about what the article shows: the links researchers are using in their articles are rotting, but these links are usually those provided by publishers, aggregators, databases, or other external actors that neither the journal nor the research control. The use of DOIs certainly helps with this, but of course persistent OSF links would be a lot better as well.

Perhaps Mr. Cohen could explain to us why he thinks the recommendations for terminology about journal article versions carefully worked out by NISO several years ago are not adequate in today’s world.

I have two copyright related questions, because I know very little about this arcane stuff. First, it seem like the safe harbor defence should not allow one to keep posting articles one knows to be illegal, deliberately waiting to be told to take them down. That should be illegal, but is it?

The second has to do with publishers setting embargo periods for accepted manuscripts (AMs). I recently wrote about this and here is the key excerpt: “What puzzles me is that the AMs published by the Agency are subject to a Federal Use license. This Federal Use license is the entire legal basis for the US Public Access Program.” The point is that if an AM is covered by the US Public Access Program, then it has an embargo period of 12 months (for now). I do not see how a publisher can set a longer embargo period for the AM, or establish any other restrictions that exceed the Federal license. Can they?

To answer your first question:

The details of the US safe harbor provisions are described here:

https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/512

They specifically state:

A service provider shall not be liable for monetary relief, or, except as provided in subsection (j), for injunctive or other equitable relief, for infringement of copyright by reason of the storage at the direction of a user of material that resides on a system or network controlled or operated by or for the service provider, if the service provider—

(A)

(i) does not have actual knowledge that the material or an activity using the material on the system or network is infringing;

(ii) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(iii) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

I am not a lawyer, but to me that would suggest to me that if you know it’s infringing, you have to act or else you’re liable.

As for Federal Use Licenses, these are only vaguely described, and as far as I know have not been tested in a court of law so their extent is unknown. A journal is certainly free to set the conditions they require for publication. If the author or their funder demands something beyond what the journal is willing to provide, the journal has the right not to publish the article. If after publication, the author author or the funder violates those conditions, then it would seem to give the journal cause to retract the article. It would likely be in an author’s best interests to find publication venues that are able to meet their funder’s requirements, and should those include a shorter embargo period than is available, then opting for immediate open access would probably be a wise choice.

First, on Section 512 of the Copyright Act: It can be confusing. The Digital Media Law Project has a very good summary explanation at http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/protecting-yourself-against-copyright-claims-based-user-content, and it links to the very helpful reorganization of Section 512 in “DMCA Safe Harbors Decoded” at http://www.jdsupra.com/post/documentViewer.aspx?fid=d58713ac-c1f4-43a2-99c8-a6f6e214322e.

David Wojick is wrong to suggest that the DMCA safe harbor might ever apply to posting articles that you know are infringing. There is no safe harbor for the deliberate act of posting infringing material. The DMCA only provides a safe harbor for sites like SocArXiv that provide a location to which users can post material. It is the user who is doing the posting, and not the site that is doing the hosting, who is liable for copyright infringement. There is no requirement for hosting sites to monitor content that is posted to ensure that it is not infringing. And the site need only take down content when, as David Crotty suggests, it knows that the content is infringing. How does it gain that knowledge? The primary mechanism is when a copyright owner sends a notice indicating that a particular work at a particular location is infringing. But that knowledge only applies to that specific instance. The hosting site does not need to assume that all copies of a work found on its site are infringing, but only needs to act on those about which a complaint has been filed.

Second, as to “Federal Use licenses”: I assume that you are referring to Section 36 of OMB Circular A-110, which gives the Federal government “a royalty-free, nonexclusive and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use the work for federal purposes, and to authorize others to do so.” There are no embargo periods specified in that specification. Furthermore, I am not aware of any federal agency that has cited Section 36 as the basis for its public access programs. I would like to learn more. The rights that are encompassed in Section 36 are much more expansive than the requirements in any of the public access programs. It would be a radical change in distribution if a Federal agency ever opted to assert all of them.

The Federal use license is not based on Section 36 of A-110. The Public Access agencies cite this section of the Code of Federal Regulations as their authority to collect and publish accepted manuscripts that flow from their funding:

“2CFR 215 § 215.36 Intangible property.

(a) The recipient may copyright any work that is subject to copyright and was developed, or for which ownership was purchased, under an award. The Federal awarding agency(ies) reserve a royalty-free, nonexclusive and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish, or otherwise use the work for Federal purposes, and to authorize others to do so.”

Note that this claim extends to articles the writing of which was not funded by the agency, even to articles written well after the award ends. The federal argument is that the research itself is part of the development of the article, so the article is developed under the award. I question this.

We are talking about the same thing. 2 CFR § 215.36 (now 2 CFR § 200.315) incorporates the guidance found in Circular A-130. Both of them provide guidance, not regulations, on the agencies that issue grants. It is up to each individual agency to make sure that its regulations match the guidance that OMB has provided.

I have a vague memory of NIH explicitly rejecting the use of this provision as a justification for its public access program, which is why your statement intrigued me. (I had also never heard it called the “Federal Use license” before.) One nasty issue that was difficult to resolve was whether providing reading access to the articles actually constituted “Federal purposes.”

I don’t have a problem with articles written after an award has ended as being considered to be products of the award and hence subject to this provision. It is why, after all, the grant is listed in the subsequent article. If the grant is not listed, then the provision should not apply.

I am more intrigued about what the grant may mean for the standard copyright transfer agreement. In my experience, they often state that exclusive rights are being transferred, but that is not possible because the Federal government already has a non-exclusive license to use the material. Does that invalidate the entire agreement? I would suspect so, but then I am not a lawyer. I wouldn’t mind seeing the Feds create their own journal of sponsored research and sell it at cost. After all, the grant agreement gives the government the right to publish the articles.

Sorry but the CFR contents are regulations (hence the R), with the force of law, unlike OMB guidance. Indeed, NIH does not use this provision, because they actually have a statutory provision (a law) for their program, unlike the Public Access agencies.

I do not believe that doing some federally funded research should give the government a right to everything I write using these results for the rest of my life. For example, I have a 1978 report in DTIC. If I now write an article using these results does DOD have a right to my article? This seems absurd to me.

Doesn’t seem so absurd (ethically, at least; I don’t know the law). Among researchers, if I collaborate on a data collection with someone, I might expect to be co-author with that person on their subsequent publications, regardless of how long after the fact they appear.

It’s not a question of co-authorship, which still remains open for debate–if I use someone else’s publicly available data set, must I make them an author or is citing them enough? There are entire fields based on meta-analyses and reuse of data. Those researchers would likely argue against your claim to authorship if your previously published data set was among those they used for a big project. Regardless, here we’re talking about obligations based on funding.

Let’s say I get an NSF grant and buy a centrifuge with the funds, do the experiments that were proposed in the grant and write them up in a paper, citing the grant in my funding line. The grant expires and I no longer receive any more funds from the NSF. 20 years later, I use that same centrifuge in a completely unrelated experiment. Can the NSF claim ownership of that new work as well? Must I include that 20 year old grant in the paper’s funding section and then follow all of the compliance rules that the NSF has put in place in the intervening 20 years? What if some of the money went into purchasing a refrigerator? Does everything done in my lab that needs to be cooled down now count as NSF-funded?

If you have an NSF grant and generate a data set, and 10 years later I use that data set (citing you), am I indentured to the NSF as well? Can they claim ownership of my paper?

I didn’t realize the point was to figure out how to use government funds for research while maintaining the minimum public access to the research that funding makes possible.

(Why do you think you get to keep the centrifuge and the refrigerator? If they revert back to some private status after your arbitrary time cutoff, it seems like they should be auctioned off instead of becoming your personal property.)

Keeping it away from the public isn’t the point. Ownership of your own scholarship, and permanent indentured servitude to a funder who only offers funds for a limited time is the issue.

(Why do you think you get to keep the centrifuge and the refrigerator? If they revert back to some private status after your arbitrary time cutoff, it seems like they should be auctioned off instead of becoming your personal property.)

Because this is the nature of the grants offered. Many grants are offered specifically to purchase equipment or to set up a center at a university (an “imaging center” for example, so each lab at the university doesn’t have to buy their own expensive microscope). It would seem pointless to offer such a grant for the purpose of purchasing equipment and then to take back all the equipment once the arbitrary length of the grant ended.

If you guys land a grant for SocArxiv, would you expect to send back the laptops you purchase for staff or the servers you buy after the grant ends? Would your authors be happy if the funder decided (without telling you in advance) that they had the perpetual right to publish all of the preprints posted on SocArxiv in their new formal journal without the author’s permission, thus preventing them from publishing in the forum of their choice? How would that go over?

If you want the grants to come with permanent strings, this needs to be stated in the terms offered for the grants, and the recipient has to decide whether it’s worth it. I’ve heard it proposed regularly that instead of grants, funds from agencies should instead take the form of “work for hire” contracts, basically the funder owns everything you do and every idea you have during the funding period. Not surprisingly, the researchers and their institutions don’t like this idea.

Also worth noting that not all grants come from public funds.

There is no ethical issue here, Philip. It is strictly a question of what the government is and is not buying with its grant contract. I do not believe that it is buying rights to future articles just because these articles include some findings from the research labor bought under the grant contract. The government is normally paying for specific research to be done.

Under the present contract language it should not get rights to an unspecified and unlimited number of articles written over an unlimited period of time after the contract ends. That should require very specific language which present contracts to not contain. As I read the present language it only gets rights to articles developed, that is written, under the award contract. That is entirely reasonable. But the Public Access agencies are claiming rights to articles written well after the award contract ends. That is wrong.

This portion of 2 CFR is entitled “OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET GUIDANCE FOR GRANTS AND AGREEMENTS.” The introduction is quite clear: “Publication of the OMB guidance in the CFR does not change its nature—it is guidance and not regulation. …The Federal agency regulations in subtitle B differ in nature from the OMB guidance in subtitle A because the OMB guidance is not regulatory.” See 2 CFR § 1.105.

You may well be right, in which case it gets very interesting because OMB guidance cannot bind grantees the way acquisition regulations do. How then are they required to surrender their rights? Clearly more research is called for. Many thanks!

Here is what DOE says on their PAGES Public Access FAQ: “For Financial Assistance Awardees, the Government retains nonexclusive and irrevocable rights to use the works published under an award for federal purposes (2 CFR § 200.315(b) (d)).” So it is 200.315(b), not the section I cited above by mistake, moving at blog speed. Section 200.315(b) may in fact be a regulation.

You have finally caught up with what I explained in my first post, and to which you objected: “We are talking about the same thing. 2 CFR § 215.36 (now 2 CFR § 200.315) incorporates the guidance found in Circular A-130. Both of them provide guidance, not regulations, on the agencies that issue grants. It is up to each individual agency to make sure that its regulations match the guidance that OMB has provided.” DOE has done this, by issuing regulations that incorporate the guidance that OMB has provided in 2 CFR § 200.315.

I am still waiting to see references in which agencies cite their regulation as the legal basis for their public access initiatives.

You have to look at each agency. For example, DOE states in 10 CFR § 600.136(a) that “Recipients may copyright any work that is subject to copyright and was developed, or for which ownership was purchased, under an award. DOE reserves a royalty-free, nonexclusive and irrevocable right to reproduce, publish or otherwise use the work for Federal purposes and to authorize others to do so.”

But if you look at the “Authority” section of the DOE Public Access Plan, you will see that the public access program is based on much more than just one DOE regulation.

If “Authority” means statutory authority, the citations do not provide it and I think it does not exist. 10 CFR § 600.136(a) is the only regulatory authority and that on its face only applies to articles the writing of which (i.e., development) is done under the grant. Many, probably most, articles are only written after the research ends.

I wonder why the Public Access FAQ cite 200.315(b) rather than 600.136(a)? Seems like an error.

Just to clarify, our “discussion” was limited to our exchanges on Twitter. Twitter is rarely the best mechanism for discussing complicated issues such as copyright. Let me assure you that a more in-depth conversation with members of the steering committee (of which I am one) would have been welcomed.

I realize this is a conversation for insiders invested in the current system, but it is amazing how out of date it seems. Surely even the contributors here realize that the way they have been doing things is not sustainable, and this is hardly at the cutting edge. There is huge anger about copyright restrictions for research publications. SciHub will not go away easily, and nor will the open access movement. Preprint servers will become increasingly used in all disciplines. Most authors could not care less about infringing the “rights” of Elsevier et al and will post whatever version they think is right. Everyone knows that a properly functioning market would have swept away these legacy publishers many years ago, as they simply cannot or will not compete on service. How about discussing some real issues, rather than “pseudo-controversies”?

I much prefer discussing pressing real world issues to debating alternative utopian visions. If you think the OA movement is somehow going to do away with copyright for scholarly publications I do not see anything to discuss. Nor do I see any evidence of “huge anger” with copyright. So far as I can tell most researchers have no interest in this issue.

SocarXiv is following arXiv, which is incredibly successful (essentially mandatory in some fields), and yet the publishers still exist. There’s no evidence they’re going anywhere, or even meaningfully changing.

To use astro-ph as an example, all astronomy journals allow (and most encourage) the “accepted version” to be uploaded to the arXiv. Consequently, the number of people who upload the version edited by the journal typesetters is quite small, probably approaching zero. The journals remind you to use the accepted version, not their typeset version, and authors are happy to go along with that. Why not?